| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 12, December 2025, pages 504-509

Atypical Presentation of Gangrenous Cholecystitis in a Patient With Diabetes Mellitus

Maryam Ahmada, Alexandra Nguyenb, c, d, Aldin Malkocb, c, Amanda Daoudb, c, Amira Barmanwallab, c, Brandon Woodwardb

aKaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, CA 91101, USA

bDepartment of Surgery, Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, Colton, CA 92324, USA

cDepartment of Surgery, Kaiser Permanente Fontana Medical Center, Fontana, CA 92335, USA

dCorresponding Author: Alexandra Nguyen, Department of Surgery, Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, Colton, CA 92324, USA

Manuscript submitted July 6, 2024, accepted December 31, 2024, published online November 28, 2025

Short title: Atypical Gangrenous Cholecystitis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc4291

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Gangrenous cholecystitis (GC) represents a severe complication of acute cholecystitis, characterized by full-thickness necrosis of the gallbladder wall. This condition arises from persistent cystic duct obstruction, causing local ischemia and inflammation. Its incidence ranges from 2% to 29.6% of acute cholecystitis cases and is associated with risk factors including male gender, age over 50, history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), and leukocytosis greater than 17,000 white blood cells/mL. GC carries significant morbidity and mortality, with increased operative complications compared to non-gangrenous acute cholecystitis. Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial to the prevention of disease progression and complications. Diagnosing GC preoperatively is challenging, particularly in diabetic patients who may lack typical symptoms such as right upper quadrant pain due to diabetic autonomic neuropathy. These patients often present with non-specific findings, increasing the difficulty of early diagnosis. This report presents a 56-year-old man with uncontrolled DM initially diagnosed with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), later found to have GC despite non-elevated liver function tests, absence of leukocytosis, and no reported history of postprandial or right upper quadrant pain. Despite imaging findings suggestive of acute cholecystitis, the absence of right upper quadrant pain and leukocytosis lowered clinical suspicion, leading to delayed diagnosis and intervention. Ultimately, intraoperative findings confirmed GC, and the patient underwent a successful laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This case highlights the complexities of diagnosing GC in diabetic patients and suggests that underlying microvascular disease and autonomic neuropathy contribute to atypical presentations. Clinicians should consider GC in diabetic patients with non-specific abdominal symptoms and maintain a low threshold for surgical intervention. Further studies are needed to elucidate the pathophysiology and clinical presentation of GC in diabetic patients and to optimize diagnostic and management strategies.

Keywords: Gangrenous cholecystitis; Diabetes mellitus

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Gangrenous cholecystitis (GC) is characterized by transmural inflammation and necrosis of the gallbladder wall and is a severe and potentially life-threatening complication of acute cholecystitis [1]. This condition occurs due to sustained cystic duct obstruction which results in vascular compromise and ischemia of the gallbladder wall [1]. Its incidence ranges from 2% to 29.6% of acute cholecystitis cases [1]. It is associated with risk factors such as male gender, age greater than 50 years, history of cardiovascular disease, history of diabetes mellitus (DM), and leukocytosis greater than 17,000 white blood cells/mL (normal range 4,000 - 11,000 cells/mL) [2]. GC is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, including an increased rate of operative complications compared to non-gangrenous acute cholecystitis [3-5]. Early diagnosis and operative intervention is critical in preventing progression of disease and decreasing the likelihood of complications [3, 4].

The preoperative diagnosis of GC is often challenging, as patients can present with non-specific clinical findings and may lack the classic signs and symptoms of acute cholecystitis [6, 7]. This is especially pertinent in patients with DM. Diabetic patients may lack the characteristic right upper quadrant pain associated with acute cholecystitis, a phenomenon thought to be attributable to underlying diabetic autonomic neuropathy [6, 7]. Patients with DM often have pre-existing microvascular disease which is thought to put them at a greater risk for gangrenous transformation in acute cholecystitis [1]. Due to diabetic patients’ increased risk of gangrenous transformation and higher likelihood of atypical presentations, it is essential to maintain high suspicion for acute cholecystitis in ill patients even in the absence of classical symptoms. Literature on atypical presentations in diabetic patients remains limited, likely due to the relatively low incidence of GC.

This report explores the case of a 56-year-old man with uncontrolled DM who was initially diagnosed with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and later found to also have GC despite non-elevated liver function tests (LFTs), an absence of leukocytosis, and no reported history of postprandial abdominal pain or right upper quadrant pain on presentation.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 56-year-old man with a past medical history of hypertension, type 2 DM, and hypothyroidism initially presented with shakiness, fever, and chills which he reported began that morning. He also reported experiencing 9 months of non-radiating epigastric abdominal pain which worsened within the past week accompanied by nausea and vomiting. He denied right upper quadrant pain and history of postprandial abdominal pain. His most recent hemoglobin A1C was 9.2% (normal range < 6.5%) and he had no known history of diabetic neuropathy, retinopathy, or nephropathy.

On exam, his abdominal right upper quadrant was non-tender, epigastric area was moderately tender to palpation, and he had a negative Murphy’s sign. Ultrasound showed evidence of gallbladder wall thickening (4.3 mm, normal < 3 mm), non-dilated common bile duct (3.9 mm, normal < 6 mm), gallbladder sludge, and no appreciable gallstones (Fig. 1). Computed tomography (CT) of abdomen and pelvis without contrast showed moderate gallbladder wall thickening with inflammatory changes in the surrounding fat and cholelithiasis (Fig. 2). At this time, labs showed no leukocytosis, non-elevated LFTs, and non-elevated lipase (Table 1). Otherwise, labs were significant for hyperglycemia (glucose 307, reference range 70 - 100 mg/dL) and a calculated anion gap of 19 (reference range 4 - 12 mmol/L) (Table 1). The patient was then admitted for management of DKA.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Abdominal ultrasound of the patient displaying thickened gallbladder wall (diameter 4.3 mm, normal < 3 mm) as well as sludge within the gallbladder. Arrow points to sludge within gallbladder. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Axial computed tomography image displaying gallbladder with evidence of moderate gallbladder wall thickening, inflammatory changes in the surrounding fat, and cholelithiasis. Arrow indicates gallbladder with thickened wall. |

Click to view | Table 1. Key Lab Values Throughout Hospital Course |

The second day of admission, the patient reported feeling better overall and that his epigastric pain had significantly improved. He denied right upper quadrant pain, fever, chills, nausea, and vomiting. On exam his right upper quadrant was non-tender, Murphy’s sign was negative, and the epigastric area was mildly tender. Labs showed no leukocytosis, non-elevated LFTs, and non-elevated lipase.

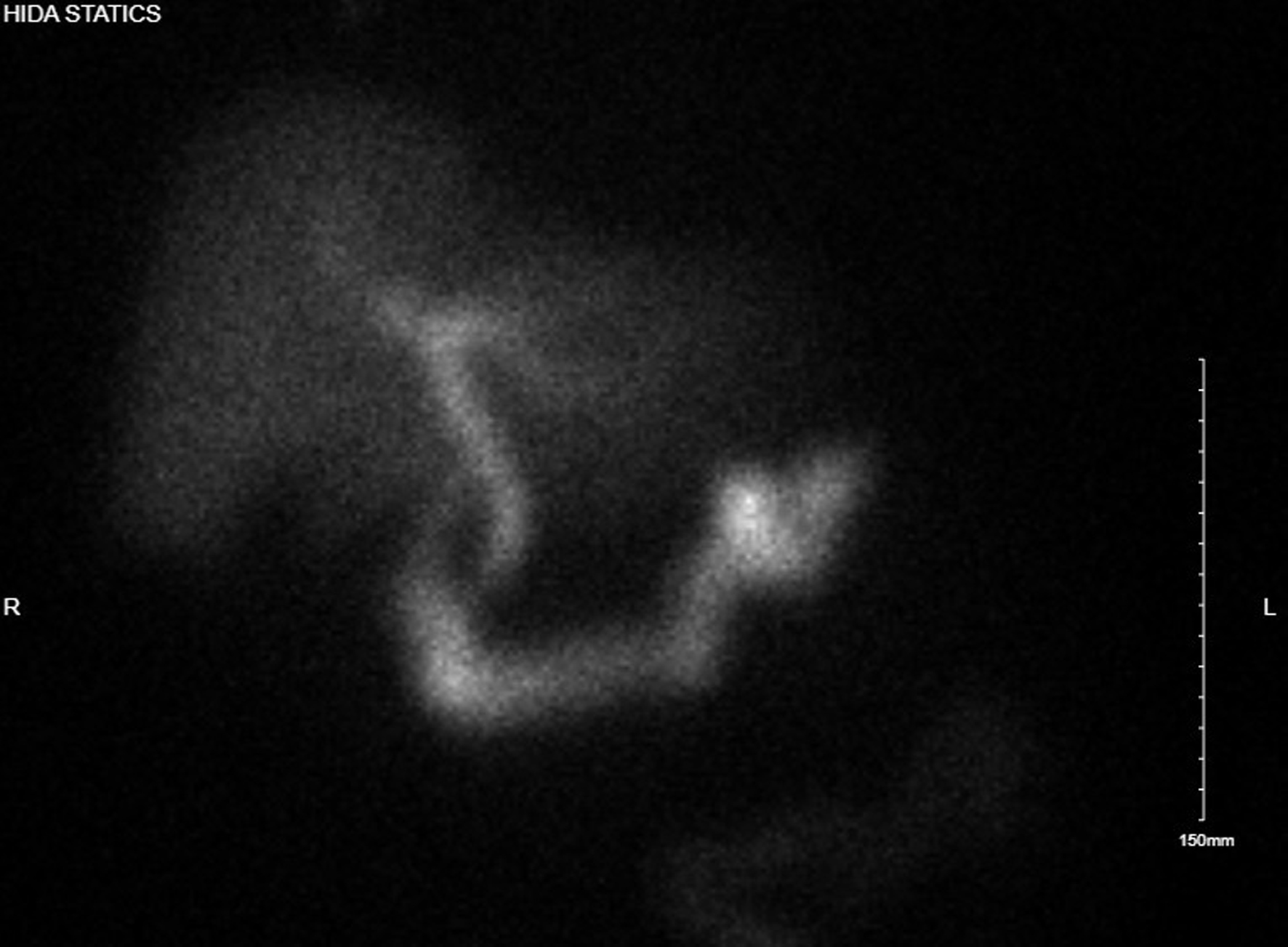

The third day of admission, the patient reported experiencing his first episode of postprandial right upper quadrant pain. A hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan was then performed which showed no uptake of tracer in the gallbladder, consistent with cystic duct obstruction (Fig. 3). Labs again showed no leukocytosis, non-elevated LFTs, and non-elevated lipase (Table 1). With the HIDA scan results and new development of postprandial right upper quadrant pain, a plan was made to perform a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid study with no uptake of tracer in gallbladder, suggesting cystic duct obstruction. |

The patient was then taken to the operating room, and during laparoscopy GC was encountered and a subtotal cholecystectomy with drain placement was then performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated, and for the remaining duration of his hospital stay, he continued to have no leukocytosis, non-elevated LFTs, and non-elevated lipase, with well-controlled pain. He was discharged on postoperative day 2, with planned follow-up in outpatient clinic.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case illustrates the diagnostic challenges of GC in patients with DM. Diabetic patients, particularly those with autonomic neuropathy, are at higher risk for atypical presentations of acute cholecystitis, which can delay diagnosis and intervention. In our case, the patient lacked the typical right upper quadrant pain and leukocytosis, common findings in acute cholecystitis, complicating the diagnostic process and leading to a delay in cholecystectomy.

Acute cholecystitis, defined as inflammation of the gallbladder, arises from obstruction of the cystic duct secondary to an impacted gallstone or gallbladder sludge [1]. Cystic duct obstruction results in increased intraluminal pressure within the gallbladder, triggering an acute inflammatory response with gallbladder wall edema [8]. GC is considered a progression of acute cholecystitis [1]. In GC, persistent cystic duct obstruction leads to vascular compromise, further increasing gallbladder wall tension and resulting in epithelial injury [1]. Damaged epithelial cell membranes release phospholipases that perpetuate the inflammatory response and cause local ischemia of the gallbladder wall [1]. Eventually, the combination of vascular insufficiency and the local inflammatory response lead to a gangrenous gallbladder with transmural necrosis [1].

Prior studies have attempted to characterize risk factors for GC, though the relatively low incidence of GC and small sample sizes limit the identification of consistent risk factors. In their retrospective cohort study of 113 cases of acute cholecystitis, Fagan et al identified a history of DM and a white blood cell count greater than 15,000 as preoperative risk factors for GC [1]. The retrospective study by Merriam et al supported the association between DM and GC and additionally identified male gender, age older than 50 years, history of cardiovascular disease, and leukocytosis greater than 17,000 as risk factors [2]. The degree of leukocytosis positively correlated with the risk for GC, with the highest risk among patients with a white blood cell count greater than 20,000 [2]. Our patient lacked leukocytosis throughout his clinical course, initially lowering the clinical suspicion for GC and other inflammatory processes. However, he carried several other risk factors, including gender, age, and history of diabetes.

The reasons behind the association between DM and GC remain unclear. One proposed mechanism is that the microvascular disease that occurs in DM might predispose patients with acute cholecystitis to gangrenous transformation [9]. Specifically, cystic artery atherosclerosis or other types of microvascular disease in patients with DM might exacerbate the ischemia that occurs as part of GC and lead to a more rapid disease progression [9]. In studies on the pathophysiology of acute cholecystitis, type 2 DM has been associated with increased risk of biliary calculi, due to underlying metabolic derangements and dyslipidemia, as well as impaired gallbladder motility secondary to visceral neuropathy [10, 11]. These same mechanisms might also predispose patients with DM to GC, though further studies need to be done to more fully elucidate the pathophysiology of GC and its contributing factors.

The classic symptoms of acute cholecystitis include constant, severe right upper quadrant pain or positive Murphy’s sign, often with associated nausea, vomiting, and fever. However, patients with GC often have atypical presentations and lack these classic features [6]. In their case-control study, Contini et al. found that 67% of patients with GC had relatively mild, subacute symptoms at initial presentation, and were more likely to have a longer delay to admission than patients with uncomplicated acute cholecystitis [12]. In their case series, Safa et al. found that only half of patients with GC had abdominal pain, and 85.7% of patients had a negative Murphy’s sign [6]. The association between a negative Murphy’s sign and GC has been noted in other studies, and is thought to be due to denervation secondary to ischemic changes [7]. The relatively nonspecific symptoms of GC make preoperative diagnosis challenging, and can lead to a delay in operative intervention.

In our case, our patient presented with progressive non-radiating epigastric pain with acute onset of fever and chills the morning of admission. Although imaging findings suggested acute cholecystitis, the clinical suspicion was initially low due to the absence of right upper quadrant pain or leukocytosis. The patient’s symptoms were thought to be due to DKA, as labs showed hyperglycemia with glucose of 307 and an anion gap of 19. Atypical symptoms and laboratory values that suggested DKA as a likely etiology made the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis challenging, ultimately leading to a delay in cholecystectomy.

Although the association between DM and GC has been established, the clinical presentation of GC in diabetic patients has not been well-studied, and it is unclear whether these patients are more likely to have atypical presentations. As a comparative process, asymptomatic myocardial infarction (MI) in patients with DM can provide insight into the clinical features and underlying mechanisms of GC in this population. Numerous studies have found that asymptomatic or painless MI occurs more frequently in diabetic patients and is a poor predictor of survival [13]. Autonomic neuropathy leading to sensory denervation is thought to be the primary cause of asymptomatic presentations in this population [13]. Histological studies of diabetic patients who died after asymptomatic MI found abnormalities of autonomic nerve fibers, and other studies have found evidence of sympathetic denervation in this population as well [13]. Given the widespread prevalence of neuropathy in patients with DM - up to 50% will develop some form of neuropathy over the course of their disease [14] - it is possible that underlying autonomic neuropathy in patients with DM can lead to atypical presentations of GC with the absence of right upper quadrant pain.

The diagnosis of GC is typically made intra-operatively when a necrotic gallbladder is discovered, but can also be made pre-operatively by the presence of specific imaging findings on CT or ultrasound. Bennett et al found that CT had a high specificity (96%) for the diagnosis of GC but a low sensitivity of 29.3% [15]. CT findings that were highly specific for GC included gas in the lumen, intraluminal membranes, irregular wall, and/or a pericholecystic abscess [15]. Our patient had imaging findings suggestive of acute cholecystitis - specifically gallbladder wall thickening - but lacked findings specific to GC.

GC has traditionally been associated with increased morbidity and mortality compared to acute cholecystitis, including a higher rate of intraoperative and postoperative complications [16]. In their retrospective single-center study, Wu et al found that GC carried a higher rate of complications, including increased rates of bile-duct injury, higher estimated blood loss (EBL), and a higher rate of conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy [5]. Interestingly, Nikfarjam et al found that GC was not an independent risk factor for mortality and found no difference in complication rates between GC and acute cholecystitis [4]. As prior studies have largely been limited by their retrospective, single-center design, further investigation is needed to definitively determine the prognosis and outcomes of GC.

Conclusion

This case highlights the challenges of diagnosing GC in diabetic patients, who often present with atypical symptoms. The lack of right upper quadrant pain and leukocytosis may lead to a lower clinical suspicion for GC, resulting in delays in surgical intervention. Diabetic autonomic neuropathy likely contributes to these atypical presentations, emphasizing the need for heightened clinical vigilance in this population. Early diagnosis and prompt surgical intervention are critical in preventing the progression of GC and reducing associated morbidity and mortality.

Learning points

GC often has atypical, nonspecific signs and symptoms, making preoperative diagnosis challenging. Patients with DM may be more likely to have an atypical presentation, lacking right upper quadrant pain with a negative Murphy’s sign, due to underlying autonomic neuropathy that results in sensory denervation. However, this population is at a higher risk for gangrenous transformation of cholecystitis, likely due to underlying microvascular disease. A high index of clinical suspicion for GC, as well as a low threshold for operative intervention, is needed for diabetic patients who present with signs and symptoms suggestive of gallbladder pathology.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

Maryam Ahmad drafted and edited the manuscript. Alexandra Nguyen assisted with conceptualization, drafting, and editing the manuscript. Aldin Malkoc, Amanda Daoud, and Amira Barmanwalla reviewed and edited the manuscript. Brandon Woodward supervised, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

DKA: diabetic ketoacidosis; DM: diabetes mellitus; GC: gangrenous cholecystitis; LFTs: liver function tests; MI: myocardial infarction

| References | ▴Top |

- Fagan SP, Awad SS, Rahwan K, Hira K, Aoki N, Itani KM, Berger DH. Prognostic factors for the development of gangrenous cholecystitis. Am J Surg. 2003;186(5):481-485.

doi pubmed - Merriam LT, Kanaan SA, Dawes LG, Angelos P, Prystowsky JB, Rege RV, Joehl RJ. Gangrenous cholecystitis: analysis of risk factors and experience with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1999;126(4):680-685; discussion 685-686.

pubmed - Yeh DD, Cropano C, Fagenholz P, King DR, Chang Y, Klein EN, DeMoya M, et al. Gangrenous cholecystitis: Deceiving ultrasounds, significant delay in surgical consult, and increased postoperative morbidity! J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(5):812-816.

doi pubmed - Nikfarjam M, Niumsawatt V, Sethu A, Fink MA, Muralidharan V, Starkey G, Jones RM, et al. Outcomes of contemporary management of gangrenous and non-gangrenous acute cholecystitis. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13(8):551-558.

doi pubmed - Wu B, Buddensick TJ, Ferdosi H, Narducci DM, Sautter A, Setiawan L, Shaukat H, et al. Predicting gangrenous cholecystitis. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16(9):801-806.

doi pubmed - Safa R, Berbari I, Hage S, Dagher GA. Atypical presentation of gangrenous cholecystitis: A case series. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(11):2135.e1-2135.e5.

doi pubmed - Dhir T, Schiowitz R. Old man gallbladder syndrome: Gangrenous cholecystitis in the unsuspected patient population. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;11:46-49.

doi pubmed - Chaudhry S, Hussain R, Rajasundaram R, Corless D. Gangrenous cholecystitis in an asymptomatic patient found during an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:199.

doi pubmed - Onder A, Kapan M, Ulger BV, Oguz A, Turkoglu A, Uslukaya O. Gangrenous cholecystitis: mortality and risk factors. Int Surg. 2015;100(2):254-260.

doi pubmed - Serban D, Balasescu SA, Alius C, Balalau C, Sabau AD, Badiu CD, Socea B, et al. Clinical and therapeutic features of acute cholecystitis in diabetic patients. Exp Ther Med. 2021;22(1):758.

doi pubmed - Pazzi P, Scagliarini R, Gamberini S, Pezzoli A. Review article: gall-bladder motor function in diabetes mellitus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14(Suppl 2):62-65.

doi pubmed - Contini S, Corradi D, Busi N, Alessandri L, Pezzarossa A, Scarpignato C. Can gangrenous cholecystitis be prevented? A plea against a "wait and see" attitude. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(8):710-716.

doi pubmed - Chiariello M, Indolfi C. Silent myocardial ischemia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 1996;93(12):2089-2091.

doi pubmed - Callaghan BC, Cheng HT, Stables CL, Smith AL, Feldman EL. Diabetic neuropathy: clinical manifestations and current treatments. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(6):521-534.

doi pubmed - Bennett GL, Rusinek H, Lisi V, Israel GM, Krinsky GA, Slywotzky CM, Megibow A. CT findings in acute gangrenous cholecystitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178(2):275-281.

doi pubmed - Ganapathi AM, Speicher PJ, Englum BR, Perez A, Tyler DS, Zani S. Gangrenous cholecystitis: a contemporary review. J Surg Res. 2015;197(1):18-24.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.