| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, January 2026, pages 000-000

Long-Term Disease-Free Survival After Sorafenib-Combined Chemotherapy for Refractory Metastatic Testicular Germ Cell Tumor: A Five-Year Follow-Up

Hong Liang Gaoa, d, Yue Jia Dub, d, Zi Yi Wua, Tian Yu Caoa, Yuan Jie Lib, e, Jing Lib, c, e

aDepartment of Urology, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University (Naval Medical University), Shanghai, 200433, China

bDepartment of Precision Medicine, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University (Naval Medical University), Shanghai, 200433, China

cSchool of Health Science and Engineering, University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, 200093, China

dThese authors contributed equally to the study.

eCorresponding Authors: Yuan Jie Li and Jing Li, Department of Precision Medicine, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University (Naval Medical University), Yangpu District, Shanghai 200433, China

Manuscript submitted October 25, 2025, accepted December 13, 2025, published online January 4, 2026

Short title: Sorafenib in Refractory Metastatic TGCT

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5235

| Abstract | ▴Top |

The management of late-stage refractory metastatic non-seminomatous germ cell tumor (NSGCT) remains a significant challenge in oncology. While first-line BEP (bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin) chemotherapy achieves high cure rates in most patients, those who progress after multiple lines of therapy have a poor prognosis and limited treatment options, highlighting a critical gap in effective treatment decision-making for advanced disease. This previously reported case is an example of precision medicine and also demonstrates that the therapeutic effect is not transient but can be sustained long term, as shown by our 5-year follow-up. This 21-year-old man with widely metastatic NSGCT initially underwent orchiectomy followed by BEP chemotherapy, which achieved only a partial response. He then experienced rapid progression with new lung and brain metastases that were unresponsive to second-line GEMOX (gemcitabine + oxaliplatin) chemotherapy and a programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade clinical trial. When treatment options were exhausted, comprehensive molecular profiling of a new lung lesion identified 22 oncogenic alterations, including Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene (KRAS) amplification. Guided by a molecular tumor board (MTB) recommendation, an off-label regimen of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and sorafenib (CPS) was initiated, targeting the MAPK pathway. The tumor again developed resistance to CPS, prompting a rational BEP rechallenge that resulted in disease stabilization and ultimately a durable long-term remission. At the 5-year follow-up in July 2025, the patient remains disease-free with a normal quality of life. We present this N-of-1 case to illustrate how molecularly guided post-resistance treatment can inform therapeutic decision-making in advanced disease. Tumors are highly complex, and gene-cancer interaction is still being elucidated. In this context, key learning points from this case include: 1) the critical role of iterative molecular profiling and MTB guidance in identifying actionable targets when standard options are exhausted; 2) the potential value of rational drug rechallenge informed by the evolving “tumor ecology;” and 3) the necessity of long-term follow-up to link treatment responses with biomarkers, allowing N-of-1 learning that may offer a template for personalized management in similarly challenging cases.

Keywords: Non-seminomatous germ cell tumor; Precision oncology; KRAS amplification; Long-term survival

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Non-seminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCTs) represent a heterogeneous subgroup of testicular cancers, accounting for approximately 40% of all germ cell tumors. Despite high cure rates with first-line bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy in early-stage disease, patients with refractory metastatic NSGCT face a dismal prognosis, with historical 5-year survival rates < 10% in heavily pretreated populations. The management of such ultra-refractory cases remains challenging due to limited therapeutic options and the absence of standardized guidelines.

This case is unique in its demonstration of durable disease-free survival (DFS) through a precision oncology approach in a patient with widely metastatic, platinum-resistant NSGCT. The patient initially achieved partial response (PR) with BEP but rapidly progressed despite second-line GEMOX (gemcitabine + oxaliplatin) chemotherapy and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibition. Molecular profiling revealed Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene (KRAS) amplification, prompting off-label treatment with carboplatin, paclitaxel, and sorafenib (CPS), targeting the MAPK pathway [1]. Subsequent resistance led to rational rechallenge with BEP, culminating in sustained remission at 5-year follow-up. This trajectory highlights the critical role of iterative molecular profiling, adaptive therapy, and molecular tumor board (MTB)-guided decision-making in overcoming treatment-refractory disease.

Key precedents supporting this approach include studies demonstrating KRAS-targeted strategies in preclinical models and clinical trials of sorafenib in RAS-driven cancers [2]. The use of MTBs to navigate complex molecular landscapes has been validated in refractory solid tumors [3], while BEP rechallenge has shown efficacy in platinum-sensitive relapse settings [4]. This case underscores the transformative potential of integrating molecular insights into clinical practice for ultra-refractory cancers.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations (patient information and clinical findings)

A previously healthy 21-year-old male presented in early 2019 with right-sided testicular swelling and pain. No significant medical, family, psychosocial, or genetic history was reported. This was the initial presentation; no past interventions were recorded.

Significant physical examination and clinical findings included: 1) laboratory tests showing markedly elevated serum tumor markers, including alpha-fetoprotein (alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)), beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH); 2) imaging findings, with enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans revealing the presence of pulmonary and retroperitoneal metastases.

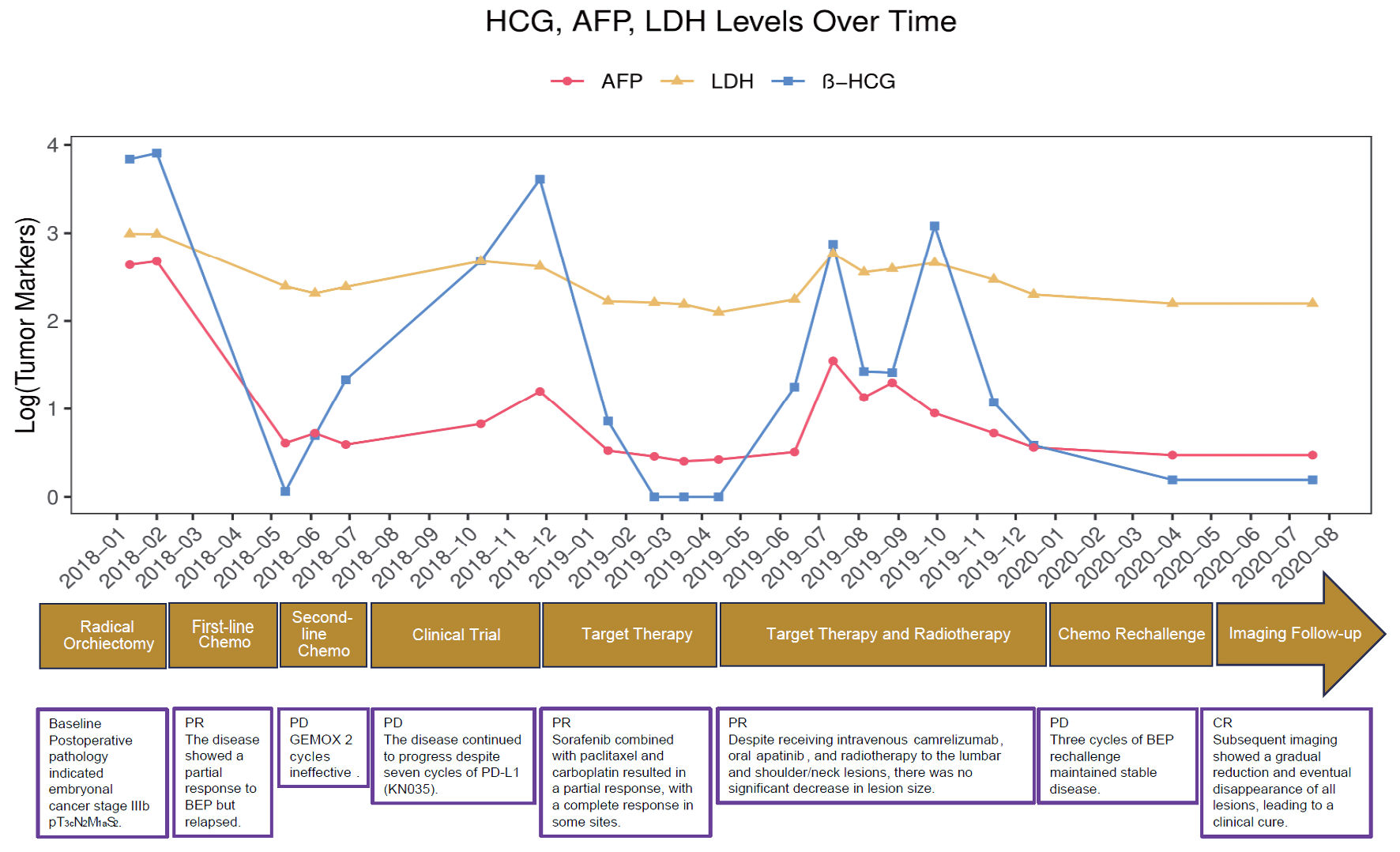

Figure 1 illustrates the systematic treatment timeline and corresponding changes in tumor biomarkers.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Tumor marker levels (hCG, AFP, LDH) and patient treatment timeline. The graph illustrates the patient’s tumor marker levels over time, corresponding to various stages of treatment and clinical response. The timeline at the bottom details the specific therapies administered, including orchiectomy, several chemotherapy regimens, targeted therapy, and radiotherapy. The markers track the patient’s condition from initial partial response and relapse to a final clinical cure. hCG: human chorionic gonadotropin; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; BEP: bleomycin + etoposide + cisplatin; GEMOX: gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin; PD: progressive disease; PD-L1: programmed cell death ligand 1; PR: partial response; CR: complete response. |

Diagnosis

The patient underwent a right radical orchiectomy. Histopathological examination confirmed a malignant germ cell tumor, specifically an NSGCT predominantly composed of embryonal carcinoma.

Whole-body CT scans were used for staging. The patient was staged as stage IIIb (pT3cN2M1aS2) according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system.

The primary diagnostic challenge involved accurately differentiating this aggressive germ cell tumor from other histological subtypes, such as seminoma or yolk sac tumor. This challenge was definitively resolved through comprehensive pathological and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of the orchiectomy specimen. The final pathological diagnosis confirmed a malignant germ cell tumor, specifically classified as an NSGCT with a predominant component of embryonal carcinoma.

The patient belonged to a poor-prognosis group based on the International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCCG) classification, facing a high risk of treatment failure due to the presence of non-pulmonary visceral metastases (brain) and primary resistance to cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Given the development of resistance to standard therapies, the patient underwent comprehensive molecular profiling. CT-guided biopsy of a metastatic lesion and subsequent genomic sequencing revealed 1,469 amplified genes at the copy number variation level, which included 22 oncogenes. Within this genomic landscape, KRAS gene amplification was identified as a key event, being a well-recognized oncogenic driver and a potential therapeutic target.

Treatment

The patient’s treatment course was dynamic and adapted to the disease response, as visualized in the imaging timeline (Fig. 1).

Following orchiectomy, the patient received first-line chemotherapy with four cycles of BEP, achieving a PR.

Upon rapid disease progression with new lung and brain metastases, second-line chemotherapy with GEMOX was administered but was ineffective. Subsequently, the patient was enrolled in a clinical trial receiving the PD-L1 inhibitor KN035, which also failed to control the disease. Whole-brain radiotherapy was utilized for symptomatic control of brain metastases.

Given resistance to standard therapies, a CT-guided biopsy of lung metastasis was performed. Genomic analysis revealed KRAS amplification. Based on the recommendation of the MTB, the patient was treated with the off-label combination of CPS, targeting the MAPK pathway downstream of KRAS. The CPS regimen resulted in a significant tumor response.

The emergence of a new enlarged left supraclavicular lymph node in August 2019 indicated acquired resistance to CPS. An alternative vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) inhibitor (anlotinib) was trialed without success. Radiotherapy was administered for a newly identified destructive L2 vertebral metastasis. In December 2019, BEP chemotherapy was rationally reintroduced.

Follow-up and outcomes

Response to CPS

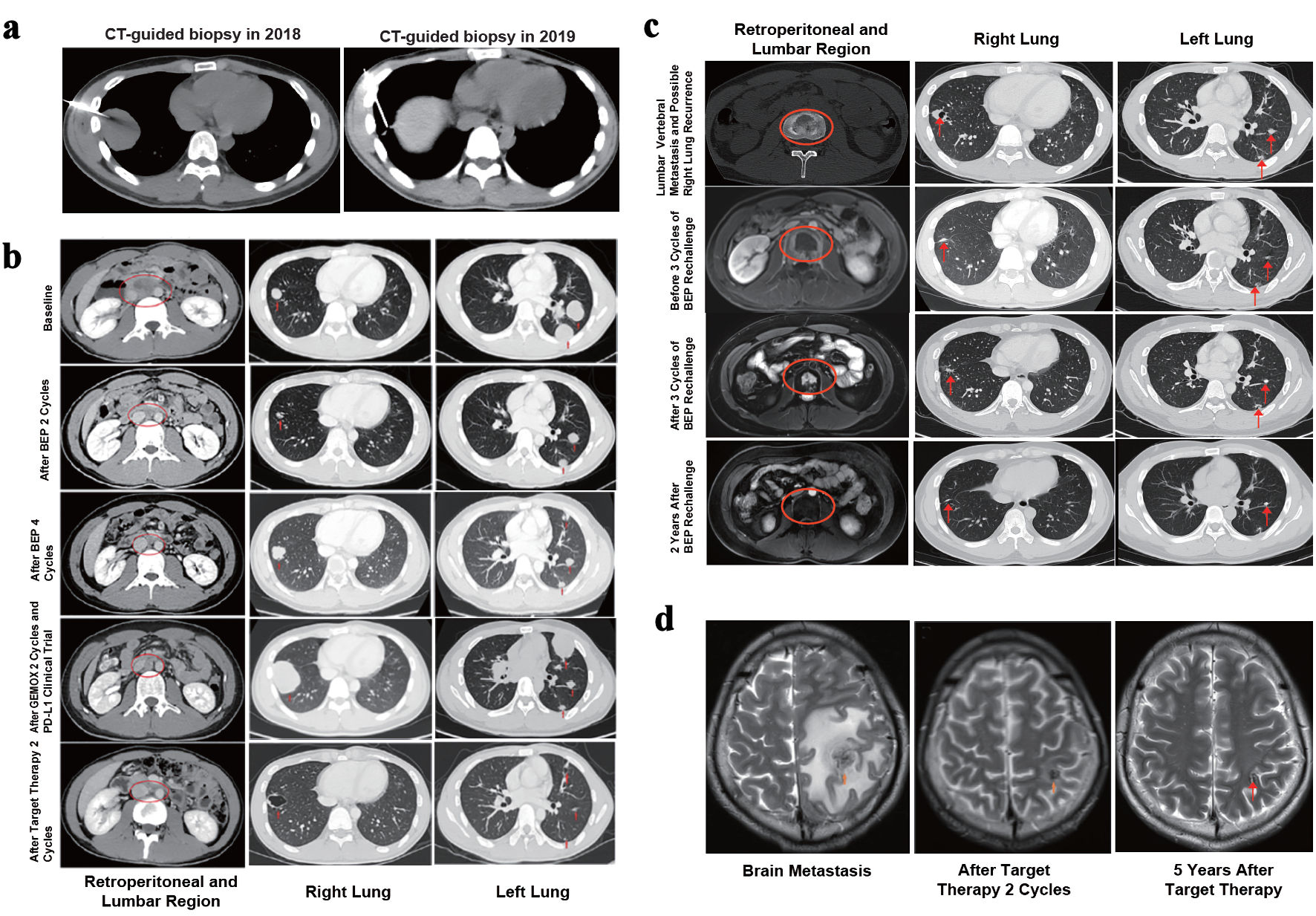

After two cycles of CPS, the patient achieved a complete response (CR) in the thoracic region/right lung and brain metastases, and a PR in the left lung (Fig. 2a). Tumor markers were normalized (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Imaging changes throughout the entire treatment and follow-up process. (a) CT-guided biopsy in 2018 and 2019. (b, c) Imaging changes in the retroperitoneum, lumbar vertebral bodies and bilateral lungs throughout the entire treatment and follow-up process. The oval circles marked the metastatic lesions in the retroperitoneal lymph nodes and lumbar vertebral bodies, and the arrows indicated the bilateral lung lesions. Treatment and follow-up time points were shown on the left. (d) Changes shown on brain MRI of metastatic lesions in the left frontal lobe (arrow) throughout the entire treatment and follow-up process. The treatment and follow-up time points were shown below. CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; BEP: bleomycin + etoposide + cisplatin. |

Response to BEP rechallenge

Following three cycles of reintroduced BEP, imaging showed stable disease (SD), which was considered a clinically meaningful outcome. Subsequent follow-up demonstrated gradual and sustained improvement.

Long-term survival

By July 2025, at the 5-year follow-up, the patient had resumed normal social and professional activities with no evidence of recurrence, achieving long-term DFS.

Important follow-up test results

Serial imaging (CT, MRI) conducted over the follow-up period (2021 - 2025) consistently showed regression or stability of metastatic lesions (Fig. 2b-d).

Intervention adherence and tolerability

The patient tolerated the multiple lines of therapy sufficiently to complete the planned cycles, as evidenced by the continued administration of treatments. The ability to resume a normal life indicates acceptable long-term tolerability and recovery from treatment-related toxicities, which were not explicitly detailed but were presumably managed supportively.

Adverse and unanticipated events

The primary adverse event was the development of acquired resistance to the CPS regimen. The failure of a second biopsy to yield tumor tissue for further genomic analysis was an unanticipated challenge that limited the understanding of the resistance mechanism.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This report delineates an N-of-1 clinical course in which a young patient with an NSGCT achieved long-term DFS through sustained follow-up and a molecularly guided therapeutic strategy. At the same time, the care of patients with late-stage, treatment-refractory disease cannot be reduced to drug choice alone; it requires an integrated framework that spans organizational models of care, the introduction of novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, iterative dissection of tumor genomic mechanisms, and close coordination across multidisciplinary teams. In the following sections, we therefore move beyond the single case narrative to examine how multidisciplinary tumor boards (MDT) and MTB structures, rational assay selection and re-biopsy, pathway-level reasoning, and practice-derived experience with resistance and rechallenge can be systematically combined to inform decision-making in similarly challenging scenarios.

MTB reflections

This N-of-1 journey—from BEP PR and rapid progression, through CPS-induced remission, to later resistance and BEP rechallenge—placed the care team at multiple decision inflection points where guideline-concordant options were exhausted. At each turn, management necessarily shifted from regimen selection by histology to hypothesis-driven testing of molecular dependencies and escape pathways. The following reflections distill how a continuous MDT process, with timely escalation to a MTB, reframed the problem, integrated evolving genomic evidence, and operationalized a learning-health-system approach for refractory disease.

From standard MDT to a molecularly driven strategy

Since the late 20th century, MDTs have become the standard of care, replacing single-physician decisions with coordinated, specialty-integrated management to improve outcomes [5]. In uro-oncology, the MDT typically includes a urologist, pathologist, radiologist, nuclear medicine specialist, radiation oncologist, and a precision oncology expert; after deliberation, a written plan is issued and implemented by the primary physician, who also monitors response and toxicity [6]. For diagnostically challenging or longitudinally managed patients, MDT involvement should be continuous across the disease course. When all standard-of-care therapies have been tried without success, the MDT’s next logical step is escalation to a MTB to address questions that have become fundamentally molecular.

In refractory scenarios, escalation to a MTB does not simply add experts; it reframes the problem—from “Which regimen fits this histology?” to “Which molecular dependencies and escape routes are driving this tumor, and how can we exploit or block them?” By shifting the focus from macroscopic imaging and histology to the tumor’s molecular fingerprint, the MTB extends MDT value and enables cross-tumor, biology-driven off-label strategies when no guideline pathway remains [3, 7-9]. It convenes molecular biology, genetics, bioinformatics, and clinical judgment at one table [8], using disciplined science to expose logic and vulnerabilities within seemingly chaotic progression. To sustain impact, the MTB should function as a learning health system—embedding routine re-biopsy, integrated DNA/RNA profiling, patient-derived organoids, and prospective data capture—to iteratively refine and personalize care.

Tissue (re)biopsy and genomic profiling: opening the gate to precision care

Precision medicine begins with tissue that reflects the current biology of a progressing lesion [10]. In this case, a CT-guided biopsy of a new lung metastasis yielded fresh material for sequencing. A common counterargument is that circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) can capture a broader, whole-body snapshot of metastatic heterogeneity. In practice, the question is not merely tissue versus blood, but which specimen and which assay best answer the immediate clinical question. When resources allow, performing both is optimal, and apparent discordance between tissue and ctDNA should be expected given spatial/temporal heterogeneity and assay limitations; such differences are interpretable rather than contradictory.

When only one modality can be chosen, selection should be guided by a working model of the tumor’s genomic architecture and the pre-test probability of an actionable readout. Single nucleotide variant (SNV)-dominant tumors in canonical drivers can often be profiled effectively with ctDNA. By contrast, when copy-number alterations (CNV) predominate or gene fusions are suspected, tissue testing should be prioritized: amplification is fundamentally copy-number biology, so low-coverage whole-genome sequencing is a practical route to robust CNV calls, whereas fusion-driven tumors generally require RNA sequencing for accurate detection. Combining both DNA and RNA profiling helps minimize diagnostic blind spots [11]. Just as important, assay choices should be aligned upstream with the biopsy site, disease phase, and clinical intent (e.g., drug selection versus resistance mechanism discovery).

Finally, because many metastatic cases will not yield directly druggable variants, building patient-derived organoids in parallel is a forward-looking platform for functional testing and drug-sensitivity assessment, complementing genomics and improving the odds of a clinically actionable signal.

From KRAS amplification to downstream blockade: how the MTB reasoned

There is no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug that directly targets KRAS amplification; most KRAS inhibitors address specific point mutations (e.g., G12C) [2]. The board therefore reasoned at the pathway level. Amplification increases KRAS abundance, driving chronic activation of the MAPK cascade (RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK) and creating pathway addiction [12]. If the hyperactive master switch cannot be inhibited directly, intercepting the signal downstream at RAF or MEK may still collapse the oncogenic circuit [13].

Sorafenib, a multikinase tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) with RAF activity (C-RAF and wild-type B-RAF) in addition to VEGFR/platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), was prioritized for its potential to inhibit MAPK signaling [14]. Preclinical and case-level evidence suggests that RAF inhibition—or multikinase inhibition that embeds RAF activity—can restrain tumors with KRAS alterations, including amplification [15]. On this basis, the MTB recommended carboplatin plus paclitaxel to rapidly debulk disease [16], combined with sorafenib as the precision component aimed at the MAPK axis [17]. The off-label nature of sorafenib was made explicit.

Anticipating resistance was part of the initial plan. The board mapped plausible bypass routes—activation of PI3K–AKT–mTOR, MEK/ERK mutations downstream of RAF, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mediated feedback—so that, if progression occurred, the team could promptly adjust their treatment strategy without delay [17]. Unfortunately, at subsequent progression, a second CT-guided lung biopsy did not yield adequate tumor tissue for additional genomic profiling, limiting our ability to molecularly track the resistance mechanism.

Resistance and rechallenge: learning from tumor ecology

After a period of control on CPS, late-2019 imaging documented new cervical nodal and vertebral metastases—clear evidence of acquired resistance; a subsequent trial of an alternative VEGFR inhibitor also failed, arguing against angiogenesis as the dominant resistance mechanism and instead pointing to MAPK bypass or activation of parallel survival pathways [18]. The team re-introduced BEP and achieved stable disease (SD), a clinically meaningful containment in a heavily pretreated setting; this decision reflects a practice-derived paradigm in which tumors can regain sensitivity after a drug-free interval [19, 20], making “chemotherapy rechallenge” a pragmatic challenge to the dogma of irreversible resistance [20], provided patient selection is stringent (e.g., adequate platinum-free or progression-free intervals) [21]. Mechanistically, rechallenge rests on four principles: 1) reversibility of resistance, whereby removal of selective pressure permits re-expansion of sensitive clones (“resistance reversion”); 2) clonal selection and heterogeneity, through which prior lines reshape tumor ecology and create windows in which earlier agents can again be effective; 3) chemo-switch/cross-sensitization, where prior cytotoxic exposure primes enhanced susceptibility to another drug—or to the same agent on re-exposure; and 4) toxicity washout, allowing host recovery (e.g., from myelosuppression or neuropathy) for safe re-administration [22]. Not all patients are suitable for chemotherapy rechallenge; the key prerequisite is having an adequate treatment-free interval (such as a “platinum-free interval” or “progression-free interval”) to optimize the benefit-risk balance [4]. Taking testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT) as an example, authoritative guidelines such as the European Association of Urology (EAU) and National Health Service (NHS) explicitly state that cisplatin rechallenge (e.g., with gemcitabine/paclitaxel, or TIP regimens) can be considered under appropriate conditions [23]. Large-center clinical experiences and laboratory data also show that platinum sensitivity can be restored via certain molecular mechanisms, further supporting the rationale for rechallenge [22, 24, 25]. First-line TGCT regimens (such as EP × 4 and BEP × 3/× 4) achieve exceptionally high response and survival rates, with long-term follow-up showing durable disease control. Combined cohorts have shown a 98.3% response rate and 5-/10-/20-year overall survival rates of 97.9%, 96.0%, and 86.0%, with very low relapse rates [26]. These data provide a benchmark for evaluating the outcomes of BEP rechallenge. In testicular cancer, the decision to proceed with rechallenge depends on several factors: 1) platinum sensitivity (short-interval progression favors high-dose chemotherapy; long-interval relapse may allow standard-dose salvage); 2) timing of relapse (early relapse within 2 years typically merits salvage chemotherapy; late relapse after 2 years is uncommon and often requires surgery, especially for non-seminoma); 3) tumor markers (clearly rising AFP/β-hCG levels justify salvage treatment even without imaging evidence, while LDH elevation alone is insufficient); 4) histological type and risk stratification (seminoma vs. non-seminoma, sites of involvement, IGCCCG risk class, and adverse features) [27-29]. Methodologically—and central to an MTB mindset—every resistance event should trigger a closed loop of re-biopsy, re-profiling, and re-modeling rather than lateral empiricism across drug lists, so that subsequent decisions remain grounded in the tumor’s evolving molecular ecology.

Conclusions

We are genuinely gratified by this outcome. In many ways, the care of this patient functioned as an N-of-1 therapeutic experiment—a rigorously reasoned, prospectively monitored trial embedded within routine practice, designed first and foremost to maximize individual benefit while generating lessons that can be generalized. Rather than treating resistance as a terminus, we treated it as a hypothesis-testing moment against tumor evolution: observe, re-biopsy when feasible, reinterpret the molecular ecology, and iteratively adapt therapy. This case is not merely a success story of personalized treatment; it is a living textbook. The shift from resistance to CPS therapy to renewed response with BEP rechallenge highlights the importance of a flexible, ecology-based strategy in advanced cancer management, where prior therapies may regain utility under evolving tumor conditions.

Looking ahead, the management of refractory germ cell tumor (GCT) should increasingly embrace an adaptive, data-driven approach. Earlier and serial molecular profiling—using both tissue and ctDNA—will be essential to track clonal evolution and guide therapeutic decisions in real time. Integrating biology-driven strategies, such as pathway-targeted interventions, rational drug combinations, and judicious off-label applications when scientifically justified, may expand treatment possibilities. Additionally, implementing dynamic monitoring with predefined clinical and molecular inflection points can ensure timely reassessment and optimization of treatment courses.

When applied systematically, this iterative framework enables knowledge gained from individual patients to be translated into broader, evidence-informed strategies—transforming N-of-1 experiences into scalable approaches that have the potential to improve outcomes for larger patient populations.

Learning points

Iterative profiling is crucial. This case underscores the pivotal role of repeated molecular profiling and timely escalation from MDT to MTB when guideline-concordant options are exhausted. Iterative assessment of the tumor’s molecular drivers—exemplified by identifying KRAS amplification—provides a biologically rational basis for tailored combination strategies.

Assay and pathway-level reasoning matter. Effective precision care depends not only on “doing sequencing” but on choosing the right tissue/blood assays and interpreting results at the pathway level. In this case, integrating CT-guided re-biopsy, CNV-aware profiling, and MAPK-pathway reasoning enabled an off-label CPS regimen that translated a genomic signal (KRAS amplification) into a coherent therapeutic plan.

Learning from resistance and rechallenge is essential. Acquired resistance should trigger a closed loop of re-biopsy, re-profiling, and re-modeling rather than empirical regimen switching. Here, CPS resistance, a failed VEGFR inhibitor trial, and subsequent BEP rechallenge illustrate how viewing the tumor as an evolving ecosystem can justify rational rechallenge, embed long-term follow-up, and support a learning-health-system approach to managing late-stage NSGCT.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Urology, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University (Naval Medical University) for their support.

Financial Disclosure

This study was supported by the National Program on Key Basic Research Project, (2022YFA1305700, Jing Li), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82372719, Xu Gao) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82272793, Jing Li)

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Author Contributions

Writing original draft/data curation: Hong Liang Gao, Yue Jia Du. Review and editing: Zi Yi Wu, Tian Yu Cao, Jing Li, Yuan Jie Li. Supervision: Jing Li, Yuan Jie Li.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

GEMOX: gemcitabine + oxaliplatin; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; BEP: bleomycin + etoposide + cisplatin; KRAS: Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; VEGFR: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; hCG: human chorionic gonadotropin; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase

| References | ▴Top |

- Lian B, Zhang W, Wang T, Yang Q, Jia Z, Chen H, Wang L, et al. Clinical benefit of sorafenib combined with paclitaxel and carboplatin to a patient with metastatic chemotherapy-refractory testicular tumors. Oncologist. 2019;24(12):e1437-e1442.

doi pubmed - Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, Price TJ, Falchook GS, Wolf J, Italiano A, et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2371-2381.

doi pubmed - El Helali A, Lam TC, Ko EY, Shih DJH, Chan CK, Wong CHL, Wong JWH, et al. The impact of the multi-disciplinary molecular tumour board and integrative next generation sequencing on clinical outcomes in advanced solid tumours. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023;36:100775.

doi pubmed - Ledermann JA. Benefits of enhancing the platinum-free interval in the treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer: more than just a hypothesis? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(Suppl 1):S9-11.

doi pubmed - Patkar V, Acosta D, Davidson T, Jones A, Fox J, Keshtgar M. Cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: evidence, challenges, and the role of clinical decision support technology. Int J Breast Cancer. 2011;2011:831605.

doi pubmed - Askelin B, Hind A, Paterson C. Exploring the impact of uro-oncology multidisciplinary team meetings on patient outcomes: A systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;54:102032.

doi pubmed - Schwaederle M, Parker BA, Schwab RB, Fanta PT, Boles SG, Daniels GA, Bazhenova LA, et al. Molecular tumor board: the University of California-San Diego Moores Cancer Center experience. Oncologist. 2014;19(6):631-636.

doi pubmed - Ballatore Z, Bozzi F, Cardea S, Savino FD, Migliore A, Tarantino V, Chiodi N, et al. Molecular Tumour Board (MTB): from standard therapy to precision medicine. J Clin Med. 2023;12(20):6666.

doi pubmed - van der Velden DL, van Herpen CML, van Laarhoven HWM, Smit EF, Groen HJM, Willems SM, Nederlof PM, et al. Molecular Tumor Boards: current practice and future needs. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(12):3070-3075.

doi pubmed - Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, Bardelli A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(9):531-548.

doi pubmed - Merker JD, Oxnard GR, Compton C, Diehn M, Hurley P, Lazar AJ, Lindeman N, et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology and College of American Pathologists Joint Review. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(16):1631-1641.

doi pubmed - Samatar AA, Poulikakos PI. Targeting RAS-ERK signalling in cancer: promises and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(12):928-942.

doi pubmed - Zhang Y, Li G, Liu X, Song Y, Xie J, Li G, Ren J, et al. Sorafenib inhibited cell growth through the MEK/ERK signaling pathway in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(4):5620-5626.

doi pubmed - Wilhelm S, Carter C, Lynch M, Lowinger T, Dumas J, Smith RA, Schwartz B, et al. Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(10):835-844.

doi pubmed - Wheler JJ, Janku F, Naing A, Li Y, Stephen B, Zinner R, Subbiah V, et al. Cancer therapy directed by comprehensive genomic profiling: a single center study. Cancer Res. 2016;76(13):3690-3701.

doi pubmed - Bokemeyer C, Beyer J, Metzner B, Ruther U, Harstrick A, Weissbach L, Kohrmann U, et al. Phase II study of paclitaxel in patients with relapsed or cisplatin-refractory testicular cancer. Ann Oncol. 1996;7(1):31-34.

doi pubmed - Mendoza MC, Er EE, Blenis J. The Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR pathways: cross-talk and compensation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36(6):320-328.

doi pubmed - Jayson GC, Kerbel R, Ellis LM, Harris AL. Antiangiogenic therapy in oncology: current status and future directions. Lancet. 2016;388(10043):518-529.

doi pubmed - Sanchez-Ibarra HE, Jiang X, Gallegos-Gonzalez EY, Cavazos-Gonzalez AC, Chen Y, Morcos F, Barrera-Saldana HA. KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutation prevalence, clinicopathological association, and their application in a predictive model in Mexican patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235490.

doi pubmed - Afrasanie VA, Marinca MV, Alexa-Stratulat T, Gafton B, Paduraru M, Adavidoaiei AM, Miron L, et al. KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, HER2 and microsatellite instability in metastatic colorectal cancer - practical implications for the clinician. Radiol Oncol. 2019;53(3):265-274.

doi pubmed - Malone ER, Oliva M, Sabatini PJB, Stockley TL, Siu LL. Molecular profiling for precision cancer therapies. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):8.

doi pubmed - Kuczynski EA, Sargent DJ, Grothey A, Kerbel RS. Drug rechallenge and treatment beyond progression—implications for drug resistance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(10):571-587.

doi pubmed - Patrikidou A, Cazzaniga W, Berney D, Boormans J, de Angst I, Di Nardo D, Fankhauser C, et al. European Association of urology guidelines on testicular cancer: 2023 update. Eur Urol. 2023;84(3):289-301.

doi pubmed - Wernyj RP, Morin PJ. Molecular mechanisms of platinum resistance: still searching for the Achilles' heel. Drug Resist Updat. 2004;7(4-5):227-232.

doi pubmed - Xie B, Zhou X, Luo C, Fang Y, Wang Y, Wei J, Cai L, et al. Reversal of platinum-based chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer by naringin through modulation of the gut microbiota in a humanized nude mouse model. J Cancer. 2024;15(13):4430-4447.

doi pubmed - Fossa SD, Aass N, Kaalhus O, Klepp O, Tveter K. Long-term survival and morbidity in patients with metastatic malignant germ cell tumors treated with cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy. Cancer. 1986;58(12):2600-2605.

doi pubmed - Gilligan T, Lin DW, Aggarwal R, Chism D, Cost N, Derweesh IH, Emamekhoo H, et al. Testicular Cancer, Version 2.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(12):1529-1554.

doi pubmed - Urbini M, Bleve S, Schepisi G, Menna C, Gurioli G, Gianni C, De Giorgi U. Biomarkers for salvage therapy in testicular germ cell tumors. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(23):16872.

doi pubmed - Orszaghova Z, Kalavska K, Mego M, Chovanec M. Overcoming chemotherapy resistance in germ cell tumors. Biomedicines. 2022;10(5):972.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.