| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 17, Number 1, January 2026, pages 21-27

Anesthetic and Transfusion Management in Placenta Accreta Spectrum: Lessons From a Resource-Limited Setting and Mini-Review

Alma Soxhuku Isufia, Genci Hyskaa, Kastriot Dallakua, Vjollca Shpatab, Xhensila Frasheri Prendushic, Albana Shahinid, Asead Abdylie, Krenar Lilajf, Hektor Sulaf, Rudin Domif, Fatos Sadag, h

aService of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, University Hospital Center “Koco Gliozheni”, Tirana, Albania

bDepartment of Rehabilitation, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, Sports University of Tirana, Tirana, Albania

cDepartment of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Medicine, Tirana, Albania

dDepartment of Diagnostics and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Medicine, Tirana, Albania

eDepartment of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, American Hospital 3, Tirana, Albania

fDepartment of Surgery, Service of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, University of Medicine, Tirana, Albania

gDepartment of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Faculty of Medicine, University of Pristina, Pristina, Kosovo

hCorresponding Author: Fatos Sada, Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Faculty of Medicine, University of Pristina, Kosovo

Manuscript submitted September 8, 2025, accepted November 12, 2025, published online December 24, 2025

Short title: Massive Transfusion Protocol in Obstetrics

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5204

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) is a severe obstetric condition characterized by abnormal placental invasion of the myometrium, often resulting in massive hemorrhage and high maternal morbidity and mortality. Optimal management requires early recognition, multidisciplinary coordination, and prompt activation of massive transfusion protocols (MTPs). We report the case of a 41-year-old gravida 3 woman at 36 - 37 weeks of gestation, with two prior cesarean deliveries and a transverse fetal lie, who developed life-threatening hemorrhage during cesarean section for PAS. Spinal anesthesia was promptly converted to general anesthesia to allow safe surgical intervention, which included hysterectomy, hemostatic and vaginal sutures, bladder repair, and massive transfusion. Postoperatively, the patient was stabilized in the intensive care unit and discharged in good condition after 10 days. This case demonstrates that early MTP activation, rapid anesthetic adaptation, and coordinated multidisciplinary care can result in favorable outcomes even in resource-limited settings. It underscores the importance of preparedness, flexible intraoperative decision-making, and collaboration across obstetric, anesthetic, surgical, and critical care teams in the management of high-risk PAS cases.

Keywords: Placenta accreta spectrum; Anesthesia; Cesarean section; Massive bleeding; Massive transfusion protocol

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders are among the most serious complications in modern obstetrics, caused by abnormal trophoblastic invasion into the myometrium and failure of normal placental separation [1]. Their incidence has risen alongside increasing cesarean deliveries, now estimated at 1 in 333 - 533 births [2]. Major risk factors include placenta previa, prior cesarean section, advanced maternal age, multiparity, and assisted reproduction [3, 4]. PAS is classified as accreta, increta, or percreta, with reported distributions of 63%, 15%, and 22%, respectively [2].

PAS is often complicated by life-threatening hemorrhage and peripartum hysterectomy, with outcomes worsening when diagnosis is delayed or resources are limited [1, 5]. Although multidisciplinary management is recommended, practical implementation can be difficult in low-resource settings lacking blood products, interventional radiology, or surgical expertise [5].

This report highlights the challenges of managing massive hemorrhage due to PAS in a resource-limited setting, underscoring early massive transfusion protocol (MTP) activation, timely anesthetic conversion, and coordinated multidisciplinary care to achieve a favorable outcome.

For this mini-review, we performed a comprehensive search of PubMed and Scopus (January 2000 to January 2025) using MeSH terms and keywords: “placenta accreta spectrum,” “anesthesia,” “cesarean section,” “massive bleeding,” and “massive transfusion protocol.” Eligible studies included human research in English reviews, randomized trials, observational studies, and editorials. Non-English, animal, non-peer-reviewed, or inaccessible articles were excluded. Two authors (RD and ASI) screened titles and abstracts, with 39 full texts included for review. Ethical approval was waived according to institutional policy for single case reports.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

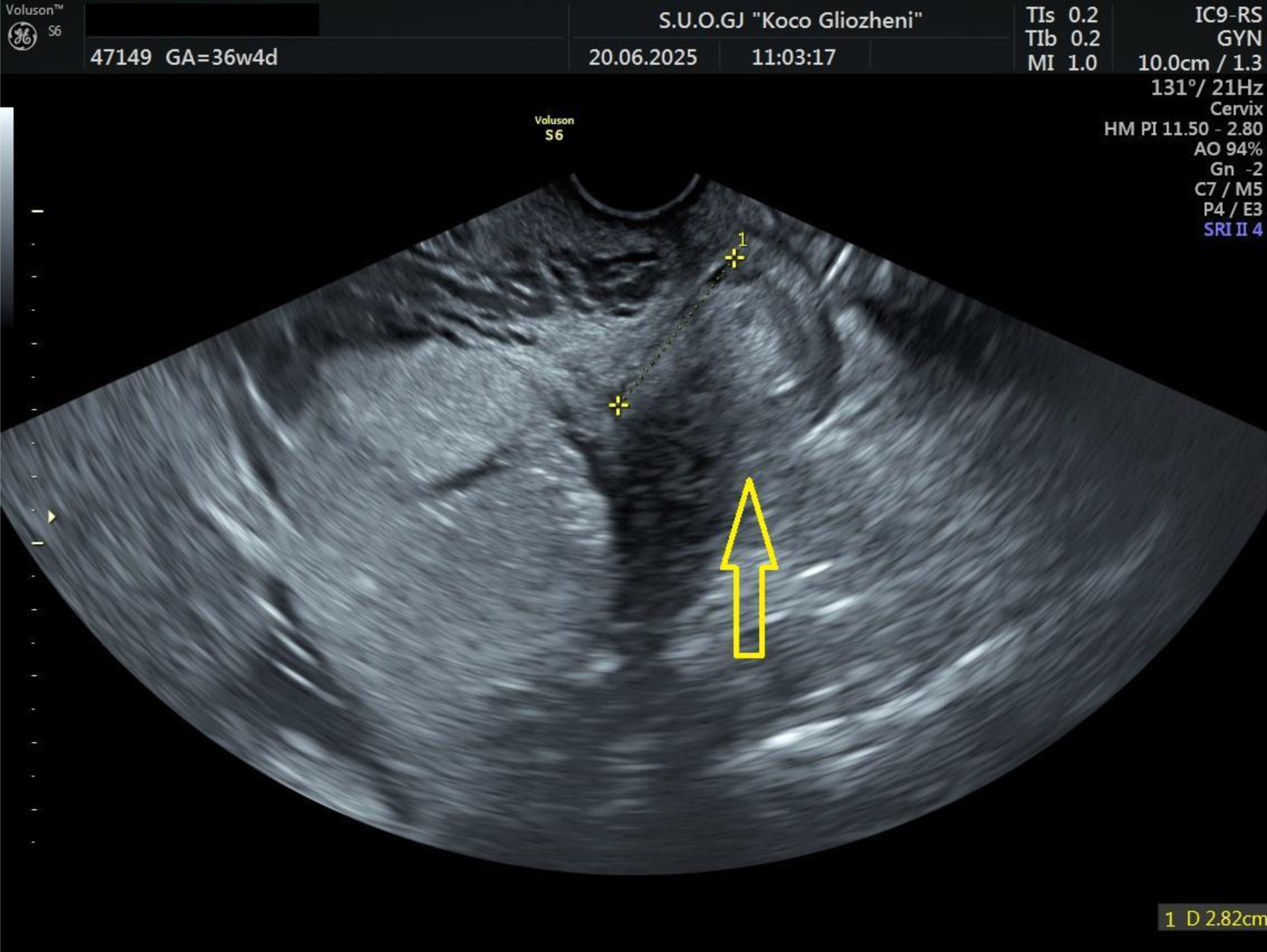

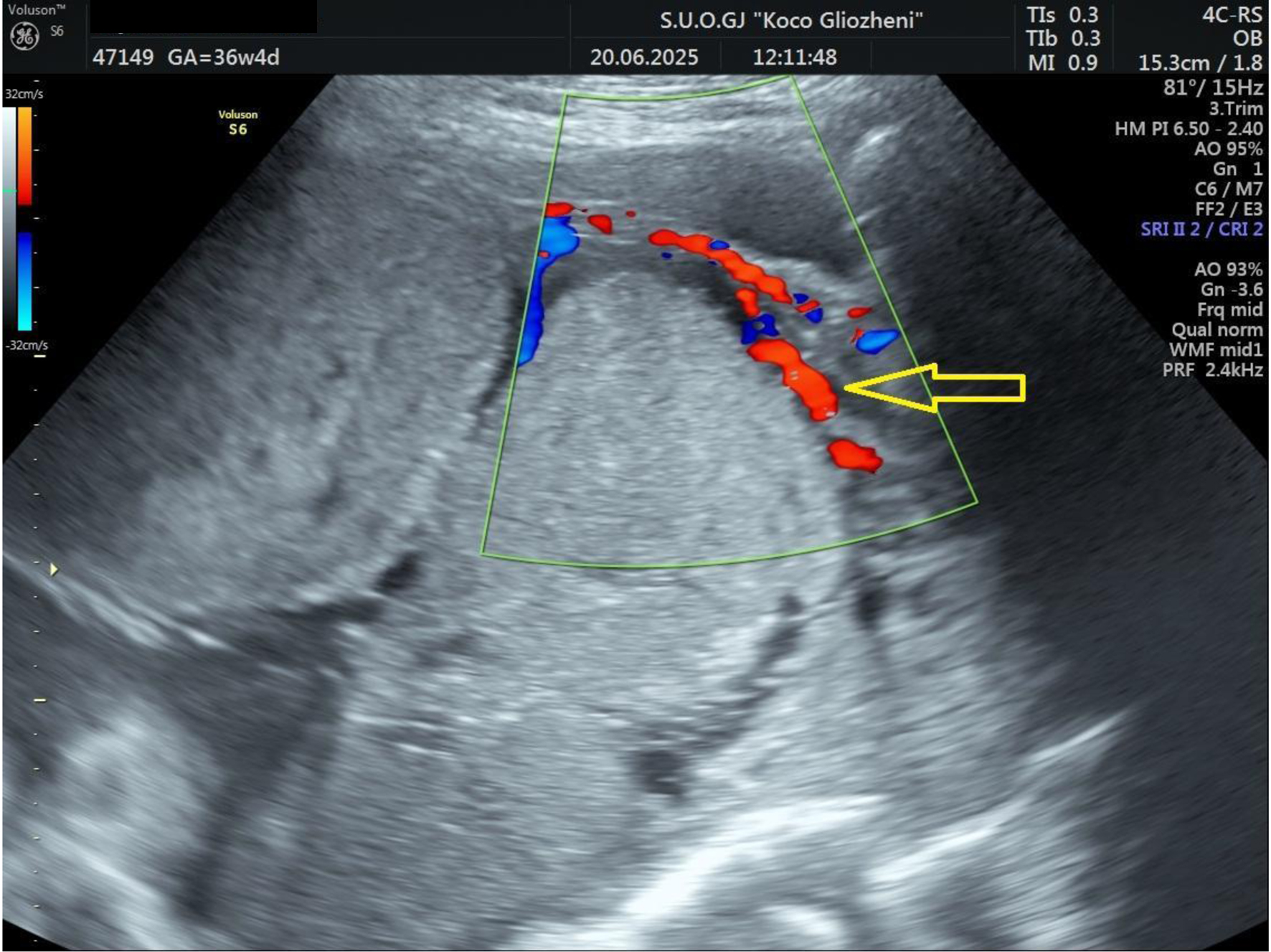

A 41-year-old woman at 36 - 37 weeks’ gestation, body mass index (BMI) 26 kg/m2, with a history of two prior cesarean deliveries and a transverse fetal lie, was admitted for evaluation. Ultrasound showed an anterior placenta completely covering the internal os, invading the full myometrial thickness up to the serosa, consistent with PAS, with marked Doppler vascularization (Figs. 1 and 2). So, elective cesarean section was indicated, and the blood bank was notified ensuring blood reserves. The surgical team was composed by obstetrician, vascular surgeon, and urologist.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Ultrasound examination showing placental tissue invading the lower myometrium (arrow). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Doppler ultrasound examination showing placental tissue invading the myometrium and extending to the serosa. Increased vascular flow was demonstrated on color Doppler ultrasound (arrow). |

Cesarean section was initiated under spinal anesthesia. After neonatal delivery, manual placental separation caused massive hemorrhage, prompting endotracheal intubation and conversion to general anesthesia. Abdominal hysterectomy was performed, with additional hemostatic sutures, bladder repair by a urologist, and vaginal hemostasis by a vascular surgeon. Bleeding was controlled after about 3 h. The baby was delivered uneventfully with an Apgar score of 9 and a birth weight of 2,725 g.

Treatment

Initial management included spinal anesthesia and crystalloids via two large-bore intravenous (IV) lines (blood pressure (BP) 110/55 mm Hg, heart rate (HR) 75 bpm). Following placental separation, hypotension (BP 50/35 mm Hg) and tachycardia (HR 78 - 135 bpm) required general anesthesia. Central venous and arterial lines were placed; norepinephrine infusion (0.05 - 0.2 µg/kg/min) maintained mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≈ 60 mm Hg. An MTP was activated, delivering 14 packed red blood cells (PRBCs), 10 fresh frozen plasma (FFP), 12 platelets, 3.5 L of crystalloids, and 2 g tranexamic acid (TXA), with active prevention of hypocalcemia and hypothermia.

Follow-up and outcomes

Surgery lasted 4.2 h with an estimated 4 L blood loss. The patient remained hemodynamically stable and was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for monitoring with the Most-Care system (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Most-Care monitor in intensive care unit. |

The cardiac output (CO) was within normal limits; however, a pulse pressure variation of 23% suggested significant hypovolemia, indicating the need for additional fluid resuscitation and vasopressor support to maintain hemodynamic stability. Both CO and stroke volume (SV) were at the lower end of the normal range, consistent with reduced preload and ongoing volume deficit.

Postoperatively, she was alert and stable (BP 90/45 mm Hg, HR 110 bpm); labs showed Hb 6.5 g/dL, platelets 75 × 103/µL, fibrinogen 223 mg/dL, pH 7.21, base excess (BE) -14.1, and lactate 5.6. Supportive therapy included two blood units, albumin, antibiotics, electrolytes, and anticoagulants. She was discharged in good condition after 10 days.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

PAS is a major obstetric complication involving abnormal placental invasion, leading to retained placenta, massive hemorrhage, and high maternal morbidity. We report a 41-year-old gravida 3 at 36 - 37 weeks with two prior cesareans and a transverse lie who developed life-threatening bleeding during cesarean delivery for PAS. Management included conversion to general anesthesia, hysterectomy, bladder repair, hemostatic suturing, and massive transfusion, emphasizing the importance of timely decision-making and multidisciplinary coordination.

PAS poses a major clinical challenge due to abnormal placental invasion into the myometrium and, in severe cases, adjacent pelvic structures. It is commonly associated with massive hemorrhage, transfusion requirements, urologic or gastrointestinal injuries, and prolonged ICU admission, contributing to high maternal morbidity and mortality [6]. Table 1 summarizes the complications associated with PAS.

Click to view | Table 1. Complications Associated With PAS |

Common complications of hysterectomy generally reported include infection (9-13%), thromboembolism (1-12%), genitourinary injury (1-2%), gastrointestinal injury (0.1-1%), and bleeding (median blood loss 156 - 660 mL) [7]. Yared et al [8] reported bladder or ureteral injuries in 32% of hysterectomy cases, recommending multidisciplinary care and prophylactic ureteral stenting to reduce morbidity. Pinto et al [9] found hysterectomy was required in 11.2% of PAS cases, while urologic injuries occurred in 8.8%.

Hessami et al published an interesting meta-analysis. This meta-analysis of 2,300 women with PAS found that cesarean hysterectomy led to higher blood loss, more transfusions, and increased genitourinary injuries compared to conservative approaches, though ICU admission and thromboembolic risks were like some conservative methods. Conservative management, including placenta left in situ or local resection, was associated with lower surgical morbidity and may preserve fertility. These findings support conservative strategies as a viable alternative to cesarean hysterectomy, but further randomized and long-term studies are needed to confirm safety and outcomes [10].

Vatanchi et al [11] observed urinary tract injuries in 25% of PAS hysterectomies, mainly cystotomy, with many developing overactive bladder symptoms. Orsi et al [12] reported a 17.7% rate of urological complications, mainly bladder injuries, associated with prior cesareans and high blood loss.

Vascular injury risk increases with obesity, adhesions, anatomical variations, and low surgical volume [13, 14]. Levin et al [15] found vascular repair was needed in 0.09% of 201,224 gynecologic surgeries, mostly during hysterectomy. Lopez-Vera et al [16] noted 4.5 hysterectomies per 1,000 obstetric procedures, with selective arterial ligation used in 88% of cases.

Bleeding remains a major concern in PAS. Jurkovic et al [17] reported significant bleeding in 38% of cesarean scar pregnancies (CSPs) managed beyond 12 weeks. Definitions of “severe bleeding” vary across studies, complicating data comparison [18-20].

During surgery, the patient experienced uncontrolled hemorrhage, vascular injury, and bladder damage - events that rapidly escalated the clinical complexity. The timely conversion from spinal to general anesthesia (intraoperatively) was a pivotal decision, enabling airway control, improved hemodynamic management, and facilitation of prolonged surgical intervention. Early recognition of the surgical challenges prompted immediate involvement of a vascular surgeon and a urologist, ensuring rapid hemostasis and bladder repair. Activation of the MTP was triggered by sustained bleeding and hemodynamic instability, allowing timely replacement of blood products and correction of coagulopathy. This coordinated, multidisciplinary response, guided by clear communication between anesthesiology, surgery, and transfusion teams, was instrumental in restoring stability and achieving a favorable outcome despite limited resources.

Massive obstetric hemorrhage most often from placental disorders or uterine atony, remains a leading cause of maternal mortality. Delays in resuscitation and surgical control are key contributors to poor outcomes. Early volume resuscitation, blood transfusions, and uterotonics were vital in this case [21]. Definitive surgical control was achieved through vessel ligation and hysterectomy.

Massive hemorrhage (typically > 2,500 mL) requires MTP activation and early fibrinogen replacement [22]. The RCOG defines “massive” antepartum hemorrhage as blood loss > 1,000 mL or any bleeding causing shock [23]. Greene et al [24] observed a 54% increase in major bleeding between 2011 and 2018, with median losses > 3,000 mL.

ACOG recommends cesarean delivery for PAS with active bleeding regardless of gestation, favoring expectant management only if bleeding ceases before 36 weeks [25]. In a review of 62 MTP cases, PAS (32%) and atony (34%) were leading causes, with favorable survival outcomes [26]. Balanced transfusion ratios (∼1:1:1 for PRBCs/FFP/platelets) improved hemostasis and reduced coagulopathy [27, 28]. Anesthetic principles of massive bleeding management are summarized in Table 2.

Click to view | Table 2. Anesthetic Management of Massive Bleeding [21-28] |

Studies support a 1:1 FFP/RBC ratio for optimal hemostasis [29]. Panigrahi et al [30] found higher transfusion needs in increta/percreta (82%) than accreta (71%). Balanced resuscitation strategies, including TXA within 3 h, reduce coagulopathy and mortality [31-36]. The WOMAN trial was a randomized, double-blind study conducted across 193 hospitals in 21 countries, enrolling 20,060 women with postpartum hemorrhage who were assigned to receive either TXA or placebo. TXA significantly reduced death due to bleeding (1.5% vs. 1.9%), particularly when administered within 3 h of birth, but it did not reduce hysterectomy rates or the composite outcome of death or hysterectomy. Adverse events, including thromboembolic complications, were comparable between groups [37].

Maintaining an MAP around 50 mm Hg without hypoperfusion may also limit blood loss [38, 39]. The actual strategies to reduce massive bleeding in obstetrics are summarized in Table 3.

Click to view | Table 3. Our Practice to Reduce Massive Bleeding in Obstetrics |

The procedure began under spinal anesthesia, as initially planned by the obstetric team, with two large-bore IV accesses. When uncontrolled bleeding developed, rapid conversion to general anesthesia was essential to secure the airway and optimize hemodynamic control. Central venous and arterial lines were promptly inserted, and aggressive volume resuscitation was initiated, followed by activation of the MTP. The patient received 14 units of PRBCs, 10 units of FFP, 12 platelet units, 2 g of TXA, and continuous norepinephrine infusion (0.05 - 0.2 µg/kg/min).

Continuous monitoring of hemoglobin, lactate, and perfusion indices along with meticulous prevention of hypocalcemia and hypothermia guided intraoperative management. Despite the absence of advanced coagulation tools, clinical assessment and structured team coordination enabled effective hemostasis and hemodynamic stabilization. The patient was transferred to the ICU extubated and remained stable throughout recovery.

This case was managed in a resource-limited setting, where comprehensive coagulation monitoring was not feasible due to the unavailability of ROTEM and fibrinogen concentrate, requiring empirical initiation of the MTP. While the outcome was favorable, the single-case nature of this report and the limited postoperative follow-up restrict the generalizability of our observations. Despite these limitations, the case highlights the importance of early recognition, prompt activation of MTPs, rapid anesthetic adaptation, and coordinated multidisciplinary care in achieving successful outcomes in high-risk PAS patients, even when advanced diagnostic or monitoring tools are not available.

Conclusions

Effective management of massive obstetric hemorrhage requires prompt identification of the bleeding source and timely interventions tailored to the patient’s condition. In this case, early activation of the MTP allowed rapid replacement of blood loss with balanced blood products, while TXA was administered to support hemostasis. The decision to convert from spinal to general anesthesia was guided by hemodynamic instability and surgical complexity, enabling safe completion of hysterectomy and bladder repair. Targeted surgical measures, including compression sutures and careful hemostatic techniques, were applied when conservative methods were insufficient. Close multidisciplinary communication between obstetric, anesthetic, surgical, and critical care teams, combined with immediate blood bank support, was critical in preventing maternal morbidity and achieving a favorable outcome.

Learning points

1) Early activation of the MTP with a balanced 1:1:1 ratio and prompt use of TXA are vital to control hemorrhage and prevent coagulopathy in PAS.

2) Timely anesthetic conversion to general anesthesia and multidisciplinary coordination among obstetric, anesthetic, surgical, and transfusion teams are essential for optimal intraoperative management.

3) Vigilant monitoring and correction of hypothermia, hypocalcemia, and acidosis, can achieve favorable outcomes even in resource-limited settings.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been obtained.

Author Contributions

RD, ASI, KL, GH, and KD wrote the paper; VS, XHFP, and ASh contributed to literature searching; HS, AA, and FS contributed to language editing.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Silver RM, Barbour KD. Placenta accreta spectrum: accreta, increta, and percreta. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(2):381-402.

doi pubmed - Jauniaux E, Bunce C, Gronbeck L, Langhoff-Roos J. Prevalence and main outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(3):208-218.

doi pubmed - Abdelhafez MMA, Ahmed KAM, Mohd Daud MNB, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum: a current literature review. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. 2023;39(6):599-613.

doi - Ogawa K, Jwa SC, Morisaki N, Sago H. Risk factors and clinical outcomes for placenta accreta spectrum with or without placenta previa. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;305(3):607-615.

doi pubmed - Abouda HS, Aloui H, Azouz E, Marzouk SB, Frikha H, Hammami R, Minjli S, et al. New surgical technique for managing placenta accreta spectrum and pilot study of the "CMNT PAS" study. AJOG Glob Rep. 2025;5(1):100430.

doi pubmed - Fonseca A, Ayres de Campos D. Maternal morbidity and mortality due to placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;72:84-91.

doi pubmed - Clarke-Pearson DL, Geller EJ. Complications of hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(3):654-673.

doi pubmed - Yared G, Moussa M, Matar M, Nahle M, El Hajjar C, Mourad P, El Moghrabi A, et al. Urological outcomes and management of abnormal placental presentations: a retrospective study at a Lebanese center. Future Sci OA. 2025;11(1):2546235.

doi pubmed - Pinto PV, Freitas G, Vieira RJ, Aryananda RA, Nieto-Calvache AJ, Palacios-Jaraquemada JM. Placenta accreta spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis on conservative surgery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2025.

doi pubmed - Hessami K, Kamepalli S, Lombaard HA, Shamshirsaz AA, Belfort MA, Munoz JL. Conservative management of placenta accreta spectrum is associated with improved surgical outcomes compared to cesarean hysterectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2025;232(5):432-452.e3.

doi pubmed - Vatanchi A, Mottaghi M, PeivandiNajar E, Pourali L, Maleki A, Mehrad-Majd H. Overactive bladder syndrome following cesarean hysterectomy for placenta accreta spectrum, a cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 2025;36(5):1077-1084.

doi pubmed - Orsi M, Somigliana E, Paraboschi I, Reschini M, Cassardo O, Ferrazzi E, Perugino G. Urological injuries complicating pregnancy-related hysterectomy: Analysis of risk factors and proposal to improve the quality of care. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2025;306:106-111.

doi pubmed - Hoffman M, Buras A, Gonzales R, Shames M. Major vascular injury during gynecologic surgery. J Gynecol Surg. 2021;37:200.

doi - Wenzel HHB, Kruitwagen R, Nijman HW, Bekkers RLM, van Gorp T, de Kroon CD, van Lonkhuijzen L, et al. Short-term surgical complications after radical hysterectomy-A nationwide cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(7):925-932.

doi pubmed - Levin SR, de Geus SWL, Noel NL, Paasche-Orlow MK, Farber A, Siracuse JJ. Vascular repairs in gynecologic operations are uncommon but predict major morbidity and mortality. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(3):1059-1066.e2.

doi pubmed - Lopez-Vera EA et al. Experience in obstetric hysterectomy and vascular control in Northeastern Mexico. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2021;89(2):109-114.

doi - Jurkovic D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Salim R, Elson CJ. First-trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(3):220-227.

doi pubmed - Cali G, Timor-Tritsch IE, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Monteaugudo A, Buca D, Forlani F, Familiari A, et al. Outcome of Cesarean scar pregnancy managed expectantly: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51(2):169-175.

doi pubmed - Fu P, Sun H, Zhang L, Liu R. Efficacy and safety of treatment modalities for cesarean scar pregnancy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2024;6(8):101328.

doi pubmed - Birch Petersen K, Hoffmann E, Rifbjerg Larsen C, Svarre Nielsen H. Cesarean scar pregnancy: a systematic review of treatment studies. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(4):958-967.

doi pubmed - Papp Z. Massive obstetric hemorrhage. J Perinat Med. 2003;31(5):408-414.

doi pubmed - Guasch E, Gilsanz F. Massive obstetric hemorrhage: Current approach to management. Med Intensiva. 2016;40(5):298-310.

doi pubmed - Drew T, Carvalho JCA. Major obstetric haemorrhage. BJA Educ. 2022;22(6):238-244.

doi pubmed - Greene RA, McKernan J, Manning E, Corcoran P, Byrne B, Cooley S, Daly D, et al. Major obstetric haemorrhage: Incidence, management and quality of care in Irish maternity units. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;257:114-120.

doi pubmed - ACOG Committee Opinion No. 764: medically indicated late-preterm and early-term deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(2):e151-e155.

doi pubmed - Salmanian B, Clark SL, Hui SR, Detlefs S, Aalipour S, Meshinchi Asl N, Shamshirsaz AA. Massive transfusion protocols in obstetric hemorrhage: theory versus reality. Am J Perinatol. 2023;40(1):95-98.

doi pubmed - Vaishnav SB, Pal R, Pandey S, Shinde M, Padaliya A. Massive transfusion protocol: a boon for salvaging patients of obstetric hemorrhage. Asian Res J Gynaecol Obst. 2024;7(1):236-248.

doi - Lin VS, Sun E, Yau S, Abeyakoon C, Seamer G, Bhopal S, Tucker H, et al. Definitions of massive transfusion in adults with critical bleeding: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):265.

doi pubmed - Tanaka H, Matsunaga S, Yamashita T, Okutomi T, Sakurai A, Sekizawa A, Hasegawa J, et al. A systematic review of massive transfusion protocol in obstetrics. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;56(6):715-718.

doi pubmed - Panigrahi AK, Yeaton-Massey A, Bakhtary S, Andrews J, Lyell DJ, Butwick AJ, Goodnough LT. A Standardized approach for transfusion medicine support in patients with morbidly adherent placenta. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(2):603-608.

doi pubmed - Flint AWJ, McQuilten ZK, Wood EM. Massive transfusions for critical bleeding: is everything old new again? Transfus Med. 2018;28(2):140-149.

doi pubmed - Harvey CJ. Evidence-based strategies for maternal stabilization and rescue in obstetric hemorrhage. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2018;29(3):284-294.

doi pubmed - Kogutt BK, Vaught AJ. Postpartum hemorrhage: blood product management and massive transfusion. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43(1):44-50.

doi pubmed - Society of Gynecologic Oncology; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Cahill AG, Beigi R, Heine RP, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(6):B2-B16.

doi pubmed - Pacheco LD, Hankins GDV, Saad AF, Costantine MM, Chiossi G, Saade GR. Tranexamic acid for the management of obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4):765-769.

doi pubmed - Ahmadzia HK, Phillips JM, Katler QS, James AH. Tranexamic acid for prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: an update on management and clinical outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018;73(10):587-594.

doi pubmed - WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum hemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10084):2105-2116.

doi - Domi R, Coniglione F, Huti G, Lilaj K. Permissive strategies in intensive care units (ICUs): actual trends? Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2025;20(2):127-135.

doi pubmed - Lamontagne F, Meade MO, Hebert PC, Asfar P, Lauzier F, Seely AJE, Day AG, et al. Higher versus lower blood pressure targets for vasopressor therapy in shock: a multicentre pilot randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(4):542-550.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, including commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.