| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 11, November 2025, pages 456-460

A Rare Cause of Umbilical Discharge in a Healthy Adult: A Case Report of Patent Urachal Sinus in Primary Care

Muhammad Tarmidzi Ibrahima, Zainal Adwin Zainal Abiddinb, Mohd Shukry Mohd Khalidc, Salma Yasmin Mohd Yusufa, Noorhida Baharudina, d, e

aDepartment of Primary Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, 47000 Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia

bGleneagles Hospital, Jalan Medini Utara 4, Medini Iskandar, 79250 Iskandar Puteri, Johor, Malaysia

cDepartment of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, 47000 Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia

dCardiovascular Advancement and Research Excellence (CARE) Institute, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, Jalan Hospital, 47000 Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia

eCorresponding Author: Noorhida Baharudin, Department of Primary Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh Campus, 47000 Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia

Manuscript submitted August 26, 2025, accepted October 10, 2025, published online October 31, 2025

Short title: Patent Urachal Sinus in an Adult

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5199

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Umbilical discharge in adults is a rare presentation in primary care and is frequently misdiagnosed as superficial infections, umbilical dermatitis, or abscesses, particularly in individuals with known predisposing factors such as obesity, poor hygiene, or diabetes mellitus. However, in the absence of these risk factors, the possibility of underlying congenital anomalies such as a patent urachus should be considered, as prompt recognition and diagnosis are paramount to prevent complications such as recurrent infections, abscess formation, and even malignant transformation. We report the case of a 29-year-old healthy male who presented to a primary care clinic with a 5-day history of purulent umbilical discharge and abdominal pain without associated fever or systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed mild periumbilical erythema and purulent discharge but no palpable mass. The absence of typical risk factors for superficial infection raised clinical suspicion of an underlying pathology. Early diagnostic workup with ultrasound revealed a hypoechoic collection within the subcutaneous tissues, and subsequent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) confirmed an infected umbilical urachal sinus. The patient was promptly referred to a surgical team for inpatient management. He was commenced on intravenous amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and underwent an incision and drainage for the infected umbilical urachal sinus. He made an uneventful recovery and was arranged for an elective laparoscopic excision of the urachal remnant. This case highlights several important learning points. In adults, urachal anomalies are rare and frequently misdiagnosed as superficial infections or abscesses, especially in the context of comorbidities such as diabetes and obesity. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis, including rare congenital conditions such as a patent urachal sinus, when assessing adults presenting with umbilical discharge. It also illustrates the critical role of primary care providers in recognizing uncommon conditions, as timely recognition and diagnosis are essential for the effective management of this rare but potentially serious condition.

Keywords: Umbilical discharge; Urachus; Urachal anomalies; Urachal sinus; Adult; Primary care

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Umbilical discharge is a common manifestation of omphalitis, an infection or inflammation of the umbilicus that primarily affects newborns [1]. In adults, umbilical infection is usually associated with superficial dermatological conditions, such as dermatitis or infectious causes [2]. These infections may extend into the subcutaneous tissues, leading to the formation of an umbilical abscess. Clinically, patients often present with purulent umbilical discharge accompanied by localized erythema and tenderness. The risk and severity of abscess formation are frequently heightened in individuals with immunocompromising conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and obesity [2, 3]. In rare instances, however, umbilical discharge may indicate an underlying congenital anomaly, such as a patent urachus. The urachus is a midline structure that extends from the bladder dome to the umbilicus. Following birth, this canal normally undergoes obliteration to form a fibrous remnant known as the median umbilical ligament. In some cases, however, the process of obliteration is incomplete, giving rise to a spectrum of urachal anomalies, including a patent urachus (urachal fistula), umbilical urachal sinus, urachal cyst, and vesicourachal diverticulum [4, 5].

While most cases of umbilical discharge in adults are attributed to acquired causes, congenital anomalies should also be considered. An infected umbilical urachal sinus is particularly rare in adults and often presents with nonspecific symptoms such as umbilical discharge and lower abdominal pain, making diagnosis challenging. This report describes a rare case of an infected urachal sinus in an adult, highlighting the importance of including urachal anomalies in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with umbilical discharge and lower abdominal pain in primary care.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

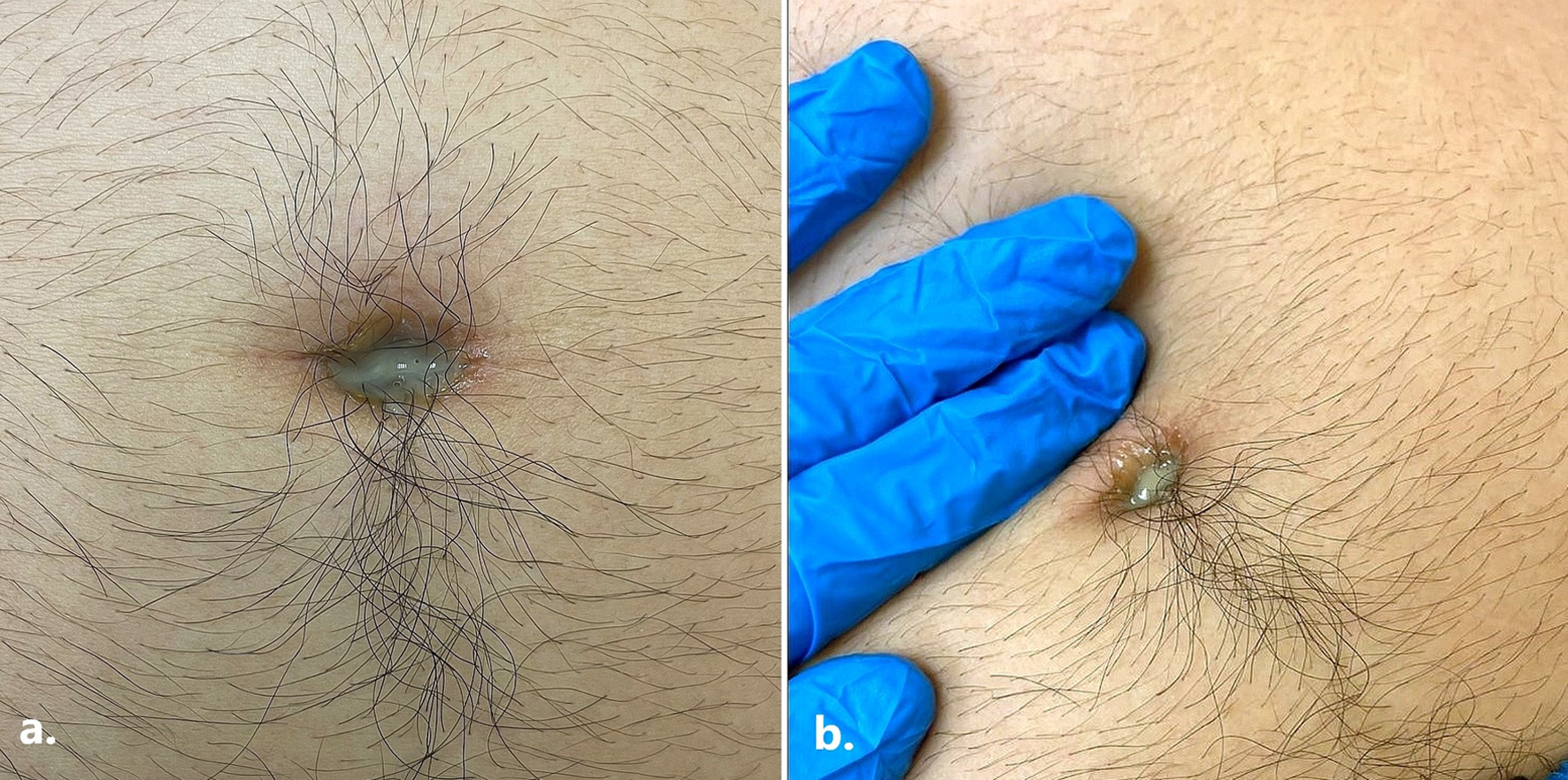

A 29-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented to a primary care clinic with a 5-day history of purulent umbilical discharge and abdominal pain. The pain was localized to the umbilical region, with a pain score of 7 out of 10. The patient did not report any fever or symptoms of a urinary tract infection, such as dysuria or frequency. Upon presentation, the patient’s vital signs were within normal limits, and his body mass index was 25 kg/m2. Physical examination revealed a tender and mildly erythematous umbilicus with purulent discharge (Fig. 1a, b). The abdomen was soft, non-tender, with no palpable masses.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) Pus discharge from the umbilicus during initial presentation at the primary care clinic. (b) Purulent discharge from the umbilicus upon gentle compression during initial presentation at the primary care clinic. |

Diagnosis

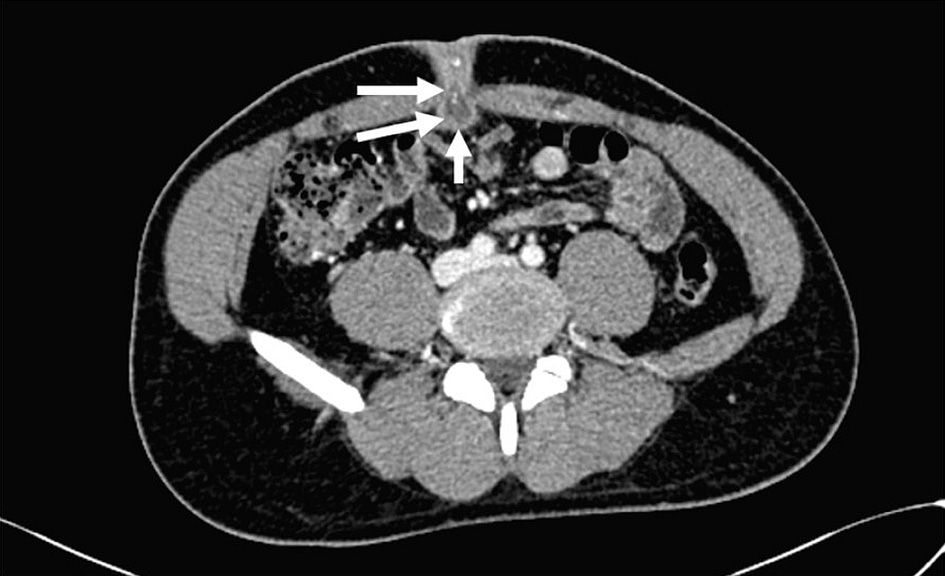

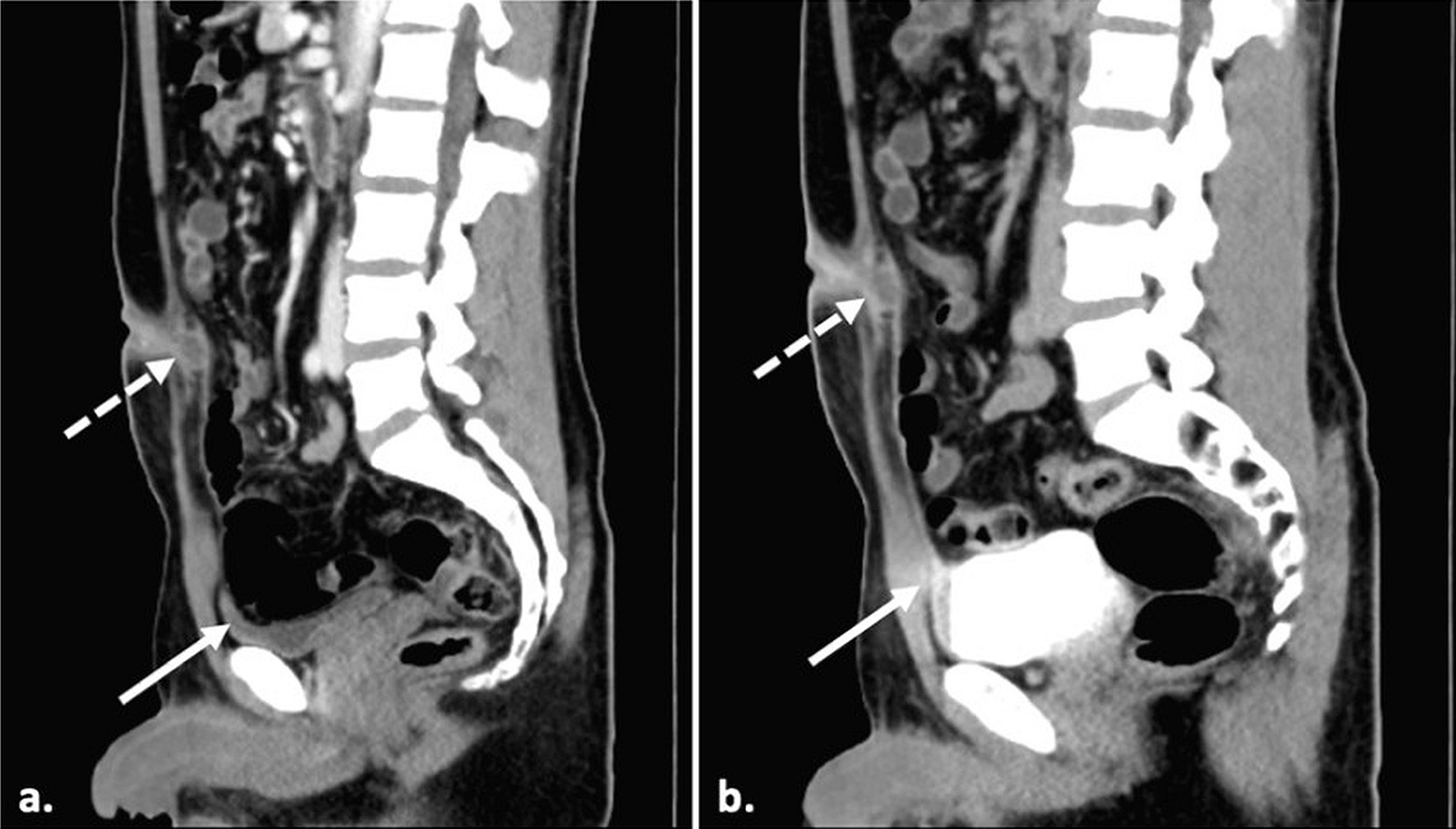

Laboratory investigations showed a normal white blood cell (WBC) count of 10 × 109/L and an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 5.6 mg/L. Renal and liver function tests were within normal parameters. The fasting plasma glucose was also within the normal range (5 mmol/L). During this consultation at the primary care clinic, a provisional diagnosis was an umbilical abscess, and the patient was referred for inpatient management, including intravenous antibiotics, imaging, and surgical evaluation. In the hospital, abdominal ultrasonography revealed an irregular hypoechoic collection within the rectus muscle and continuous with the subcutaneous tissue at the umbilical region, measuring approximately 2.2 × 2.7 × 1.9 cm. No intraperitoneal extension was demonstrated. Subsequent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a rim-enhancing fluid collection at the umbilicus measuring 2.1 × 1.7 × 1.7 cm, consistent with an infected umbilical urachal sinus (Fig. 2). Surrounding fat stranding was observed, indicative of localized inflammation. Additionally, the CT scan identified a vesicourachal diverticulum (Fig. 3a, b), characterized by a tubular tract extending from the anterior dome of the bladder towards the umbilicus.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Axial abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography image shows a blind ending, thick-walled, hypodense tubular collection (white arrows) extending posteriorly from the umbilicus into the abdominal cavity in keeping with an infected umbilical-urachal sinus. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Midsagittal CT scan images of (a) contrast-enhanced scan and (b) delayed images with a full bladder showing the partially filled vesicourachal diverticulum (solid arrow) and the infected umbilical-urachal sinus (dashed arrow). There is no evidence of communication of the umbilical-urachal sinus with the bladder lumen. |

Treatment

The patient was commenced on intravenous amoxicillin-clavulanic acid upon hospital admission. An incision and drainage procedure was performed for the infected umbilical urachal sinus. Intraoperatively, approximately 2 mL of frank pus was expressed through the umbilicus, and the posterior layer of the rectus sheath was found to be intact.

Follow-up and outcomes

The patient made an uneventful recovery following the procedure and completed a course of antibiotic therapy. A subsequent elective cystoscopy revealed normal findings, with no evidence of a vesicourachal diverticulum despite the prior CT suspicion. At follow-up in the primary care and urology clinics, the patient demonstrated complete clinical resolution. Elective laparoscopic excision of the urachal remnant was planned.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Urachal anomalies, including patent urachal sinuses, are rare congenital conditions resulting from incomplete obliteration of the urachus. The earliest documented reference to the persistence of the urachus dates back to 1550, as noted by Begg [6, 7]. Embryologically, the urachus is derived from the allantois, an extraembryonic diverticulum that develops in the third week of gestation [8]. The allantois is initially located on the posterior aspect of the yolk sac and projects into the body stalk [8]. Anatomically, the urachus extends from the anterior dome of the bladder to the umbilicus, lying within the space of Retzius, posterior to the transversalis fascia and anterior to the peritoneum [7]. Urachal anomalies can be classified into several types, including patent urachus, where the tubular structure remains open, urachal sinus and urachal diverticulum, where one end of the structure fails to close properly [7, 9]. Another type is a urachal cyst, where both ends close but the central lumen remains open; and finally, an alternating sinus, a cyst-like structure that can drain either into the bladder or the umbilicus [7, 9]. According to Ueno et al, the most common type of urachal anomaly is a patent urachus, which accounts for 47% of cases, followed by urachal cysts (30%), urachal sinuses (18%), and vesicourachal diverticulum (3%) [7]. The umbilical urachal sinus arises when the umbilical portion of the urachus does not undergo obliteration, resulting in a fusiform outpouching structure located just beneath the navel [8, 10]. This anomaly creates a potential space, which can accumulate cellular debris and lead to complications, such as infection and, less commonly, stone formation [8]. Although such complications primarily arise from urachal anomalies, other rare neonatal causes of umbilical discharge such as umbilical artery infection have also been reported, albeit exceedingly uncommon beyond the neonatal period [11].

While urachal pathologies are usually detected in infancy or childhood, they may rarely persist into adulthood, undetected and present with nonspecific symptoms such as umbilical discharge, abdominal pain, or recurrent infections. In adult primary care settings, umbilical discharge is often attributed to acquired causes, such as infected dermatoses and abscesses, which are frequently exacerbated by comorbidities like diabetes mellitus and obesity [2]. However, when conservative management fails or when the umbilical discharge recurs, a congenital etiology such as urachal anomaly should be considered. Those with infected umbilical urachal sinuses may present with a range of symptoms, including abdominal pain, fever, umbilical discharge, and the presence of a midline mass [12]. Due to the rarity of this condition and its variable clinical presentation, delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis remain significant concerns [4, 13], leading to potentially serious complications like abscess formation, peritonitis, or in rare instances, adenocarcinoma of urachal remnants [14, 15]. Furthermore, urachal anomalies can also mimic other intra-abdominal pathologies, including acute abdomen, when infection or inflammation extends beyond the umbilical region, highlighting the need to consider urachal pathology in patients presenting with lower midline pain [16]. In clinical practice, narrowing the differential diagnosis before imaging can be aided by the symptom pattern, particularly the location of pain and the presence or absence of discharge. Lower midline pain accompanied by umbilical discharge should raise suspicion for a urachal anomaly, whereas pain without discharge may suggest other intra-abdominal pathologies such as appendicitis, Meckel diverticulitis, urinary tract infections, and pelvic inflammatory disease [9, 16].

When a urachal anomaly is suspected, Yiee et al recommend ultrasonography as the initial imaging modality due to its high sensitivity in detecting various types of urachal anomalies [12]. A urachal sinus typically appears on ultrasound as a tubular, hypoechoic structure that communicates exclusively with the umbilicus [17]. While ultrasonography serves as an accessible first-line modality for primary care providers, CT can be valuable in confirming or clarifying uncertain findings, particularly in the context of an infected umbilical urachal sinus. When ultrasound fails to yield a definitive diagnosis or when no umbilical drainage is observed, CT should be considered the next imaging step. CT imaging can help differentiate between a urachal cyst and other intra-abdominal pathologies, such as appendicitis or Meckel’s diverticulitis [12]. A CT scan will usually demonstrate a thickened and fusiform dilation of the urachus at the umbilical end, with no connection to the bladder [8]. In this case, both ultrasound and CT imaging were pivotal in establishing the diagnosis of an infected umbilical urachal sinus.

Two surgical approaches are commonly employed in the management of an infected umbilical urachal sinus. The first is a single-stage procedure, in which the urachal remnant is completely excised in a single operation, provided there is no active infection. This may involve excision of the entire urachal tract, with or without a bladder cuff, and can be performed via an open or laparoscopic technique [18]. The second option is a two-stage approach, which involves initial incision and drainage of the abscess, followed by delayed excision of the urachal remnant once the infection has resolved [19]. In the present case, a two-stage approach was adopted: the patient initially underwent incision and drainage of the infected sinus along with intravenous antibiotic therapy. Elective laparoscopic excision of the urachal remnant was subsequently planned as definitive management.

Conclusions

The primary care physicians play an essential role in the early recognition and referral of this rare yet potentially serious condition. Effective communication and collaboration between the primary care and urology teams ensure timely diagnosis, appropriate imaging, definitive surgical management, and optimal postoperative recovery. Given the rarity of this condition in adults, it is imperative that primary care physicians maintain a broad differential when evaluating patients with umbilical discharge and pain.

Learning points

In adults, urachal anomalies are rare and frequently misdiagnosed as superficial infections or abscesses, especially in the context of comorbidities such as diabetes and obesity. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, including rare congenital conditions such as a patent urachal sinus, when assessing adults presenting with umbilical discharge in primary care. Timely recognition and diagnosis by the primary care physicians, in collaboration with urologists, are essential for the effective management of this rare but potentially serious condition.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the patient for providing informed consent to share his case.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

Author Contributions

MTI drafted the initial manuscript. NB and SYMY supervised MTI throughout the process, including the conception of the idea, drafting, writing, and critical revision of the case report. MSMK prepared and selected the radiological images. ZAZA provided surgical and urological contents of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, made substantial contributions, met the criteria for authorship, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the manuscript, including its accuracy and integrity.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting this case report are available within the article.

Use of AI Tools

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to improve the language and readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed, appraised, and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Abbreviations

CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: computed tomography; WBC: white blood cell

| References | ▴Top |

- Tawk A, Abdallah A, Meouchy P, Salameh J, Khoury S, Kyriakos M, Abboud G, et al. Omphalitis with umbilical abscess in an adult with a urachal remnant. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2021;15(3):966-971.

doi pubmed - Omphalitis in an adult - GPnotebook [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://gpnotebook.com/pages/surgery/omphalitis-in-an-adult.

- Zhou K, Lansang MC. Diabetes mellitus and infection. In: Feingold KR, Ahmed SF, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, et al. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA), MDText.com, Inc. 2000.

pubmed - Nogueras-Ocana M, Rodriguez-Belmonte R, Uberos-Fernandez J, Jimenez-Pacheco A, Merino-Salas S, Zuluaga-Gomez A. Urachal anomalies in children: surgical or conservative treatment? J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10(3):522-526.

doi pubmed - Schoenwolf GC, Bleyl SB, Brauer PR. Larsen’s Human Embryology (5th Edition). Elsevier; 2014.

- Begg RC. The urachus: its anatomy, histology and development. J Anat. 1930;64(Pt 2):170-183.

pubmed - Ueno T, Hashimoto H, Yokoyama H, Ito M, Kouda K, Kanamaru H. Urachal anomalies: ultrasonography and management. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(8):1203-1207.

doi pubmed - Parada Villavicencio C, Adam SZ, Nikolaidis P, Yaghmai V, Miller FH. Imaging of the urachus: anomalies, complications, and mimics. Radiographics. 2016;36(7):2049-2063.

doi pubmed - Blichert-Toft M, Nielsen OV. Diseases of the urachus simulating intra-abdominal disorders. Am J Surg. 1971;122(1):123-128.

doi pubmed - DiSantis DJ, Siegel MJ, Katz ME. Simplified approach to umbilical remnant abnormalities. Radiographics. 1991;11(1):59-66.

doi pubmed - Yamaoka T, Kurihara K, Kido A, Togashi K. Four "fine" messages from four kinds of "fine" forgotten ligaments of the anterior abdominal wall: have you heard their voices? Jpn J Radiol. 2019;37(11):750-772.

doi pubmed - Yiee JH, Garcia N, Baker LA, Barber R, Snodgrass WT, Wilcox DT. A diagnostic algorithm for urachal anomalies. J Pediatr Urol. 2007;3(6):500-504.

doi pubmed - Mrad Daly K, Ben Rhouma S, Zaghbib S, Oueslati A, Gharbi M, Nouira Y. Infected urachal cyst in an adult: A case report. Urol Case Rep. 2019;26:100976.

doi pubmed - Ashley RA, Inman BA, Sebo TJ, Leibovich BC, Blute ML, Kwon ED, Zincke H. Urachal carcinoma: clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of an aggressive malignancy. Cancer. 2006;107(4):712-720.

doi pubmed - Yu JS, Kim KW, Lee HJ, Lee YJ, Yoon CS, Kim MJ. Urachal remnant diseases: spectrum of CT and US findings. Radiographics. 2001;21(2):451-461.

doi pubmed - Kamel K, Nasr H, Tawfik S, Azzam A, Elsaid M, Qinawy M, Kamal A, et al. Complicated urachal cyst in two pediatric patients: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23(1):147.

doi pubmed - Das JP, Vargas HA, Lee A, Hutchinson B, O'Connor E, Kok HK, Torreggiani W, et al. The urachus revisited: multimodal imaging of benign & malignant urachal pathology. Br J Radiol. 2020;93(1110):20190118.

doi pubmed - Yohannes P, Bruno T, Pathan M, Baltaro R. Laparoscopic radical excision of urachal sinus. J Endourol. 2003;17(7):475-479; discussion 479.

doi pubmed - El Ammari JE, Ahallal Y, El Yazami Adli O, El Fassi MJ, Farih MH. Urachal sinus presenting with abscess formation. ISRN Urol. 2011;2011:820924.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.