| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 11, November 2025, pages 444-452

Eccrine Carcinoma Mimicking Breast Cancer: Diagnostic Challenges and Hormone Therapy as an Emerging Treatment

Yu-Han Chena, e, Santiago Imhoffa, Andrea Yue-En Sunb, Shanelly Singhc, Kayleigh Chenc, Natasha Rastogia, Alain Cagaanand, Maxwell Janoskyc, e

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, NJ, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY, USA

cHematology Oncology Physicians of Englewood, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, NJ, USA

dDepartment of Pathology, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, NJ, USA

eCorresponding Author: Yu-Han Chen, Department of Internal Medicine, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, NJ, USA; Maxwell Janosky, Hematology Oncology Physicians of Englewood, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, NJ, USA

Manuscript submitted August 18, 2025, accepted September 27, 2025, published online October 31, 2025

Short title: Eccrine Carcinoma Mimicking Breast Cancer

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5194

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Eccrine carcinoma is an exceedingly rare malignancy originating from the eccrine sweat glands, representing less than 0.01% of all cutaneous malignancies. The diagnosis of eccrine carcinoma is challenging due to its rarity. Its morphological similarities with other common tumors, especially breast cancer, further complicate assessment. It is crucial to differentiate eccrine carcinoma from metastatic breast cancer. In addition, the standard treatment is also not well established. We present the case of a 66-year-old female with a lesion on her left lip. Initially identified in 2017, the lesion recurred in 2020 and 2023. Surgeries in 2017 and 2020 achieved R0 resections, while the 2023 recurrence was an R2 resection with lymph node metastasis. Pathology suggested a possible primary breast ductal carcinoma. Immunostains were positive for estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR). However, positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) did not reveal any primary breast lesion, and there was no accessory breast tissue involvement, leading to a diagnosis of primary eccrine carcinoma. The patient declined chemotherapy and radiation therapy, opting instead for treatment with letrozole and ribociclib. Six-month follow-up imaging showed reduced lymph node size, suggesting a favorable response to therapy. This case highlights the diagnostic challenges of eccrine carcinoma, given that it mimics malignancies like breast cancer. Hormone therapy may be a potential option for hormone receptor-positive cases. Further research is essential to develop clearer diagnostic tools and standardized treatment protocols for this rare malignancy.

Keywords: Eccrine carcinoma; Breast cancer; Accessory breast cancer; Immunohistochemistry; Adnexal tumors; Recurrent skin lesions; Hormone therapy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Eccrine carcinoma is a largely understudied malignancy due to its rarity, comprising less than 0.01% of all identified cutaneous malignancies [1]. There are limited understanding and data on the prognosis of eccrine carcinoma. A study has reported that it has a mortality rate of 80% and a 10-year disease survival rate of 9% in case with metastasis [2]. It arises from the eccrine sweat glands, one of the principal adnexal structures in normal skin alongside hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and apocrine glands. Eccrine carcinoma can develop in any region of the skin and is not only restricted to the more common head and neck region [3-5]. Clinically, they typically present as pink, flesh-colored, or slightly bluish papules or nodules, varying from a few millimeters to several centimeters in size. Distinguishing features from benign counterparts include larger size, infiltrative growth pattern (poor circumscription), nuclear enlargement and pleomorphism, increased mitotic activity, rapid growth, necrosis, and ulceration. Due to its locally aggressive nature, eccrine carcinoma is associated with local recurrence rates ranging from 10% to 50% among patients who undergo local excision [6].

Diagnosing eccrine carcinoma poses a significant challenge due to its great diversity, rarity, and complexity [7]. Additionally, its morphological similarities with other common tumors, including exocrine and other neoplasms such as breast cancer, further complicate assessment. While immunohistochemistry and molecular genetics play a limited role in sweat gland tumor diagnosis, they can be valuable in ruling out alternative conditions. It is critical to rule out cutaneous metastases originating from primary adenocarcinomas, notably breast cancer, as they may morphologically and immunophenotypically resemble eccrine carcinoma [8, 9]. Similar markers could be found both in primary sweat gland carcinoma and metastatic breast cancer, which demonstrated that these markers alone are insufficient for differentiating between the two malignancies [10].

In addition to the diagnostic challenges, there is no established treatment strategy for eccrine carcinoma. Treatments such as complete excision, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy were suggested with multidisciplinary team discussion [6]. Additionally, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend androgen receptor antagonists as a possible therapy when present in certain salivary gland tumors [11]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines also suggested targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in salivary gland tumors [12]. However, there is no comment regarding estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) antagonists in eccrine cancers, necessitating further consideration and investigation.

In the hope of providing further insight into differentiating eccrine carcinoma from primary or metastatic breast adenocarcinomas, as well as exploring new treatment options for this rare cancer, we present a case of a patient with recurrent lip lesions diagnosed as eccrine carcinoma and successfully treated with hormone therapy tailored to receptor characteristics.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

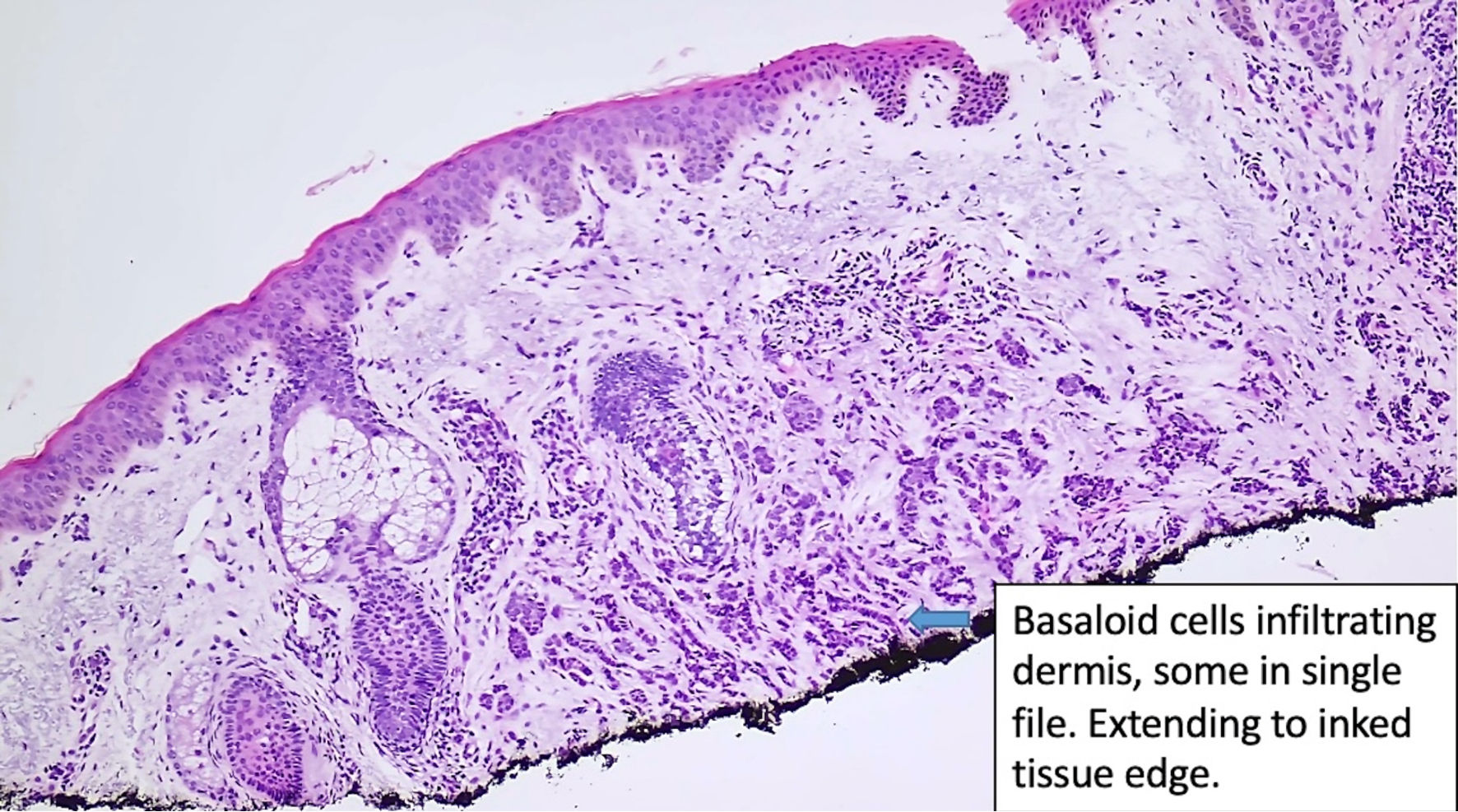

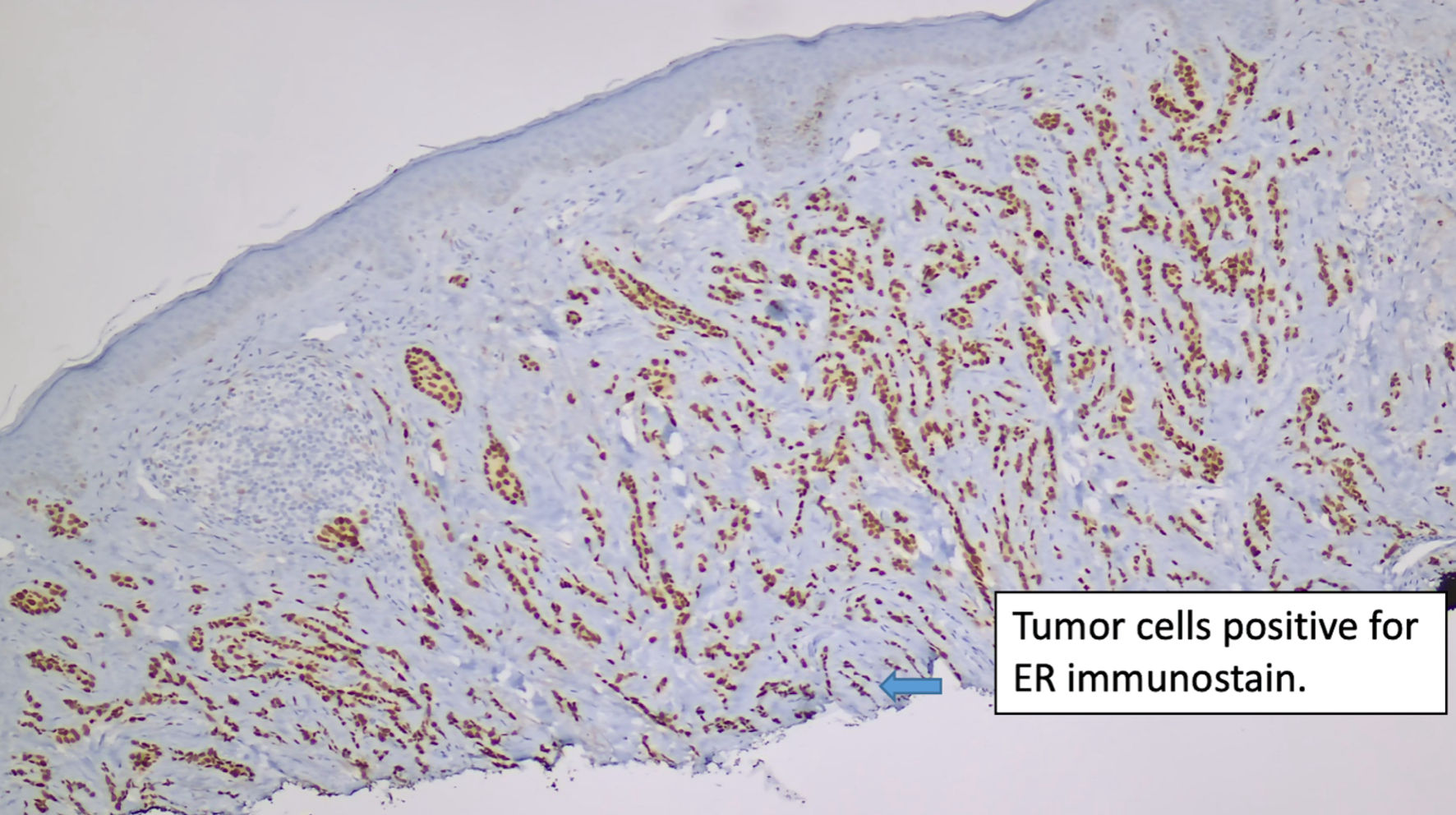

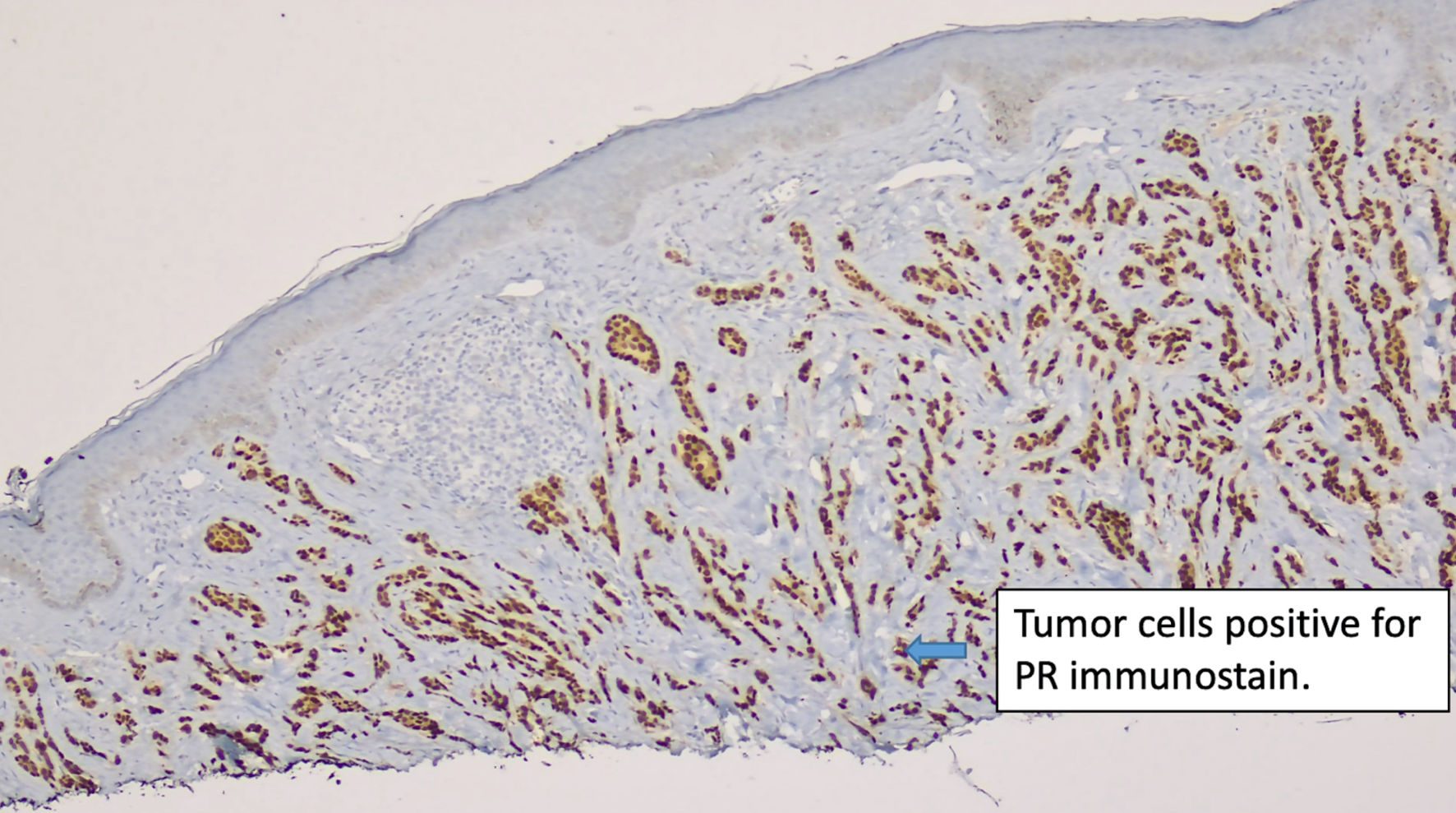

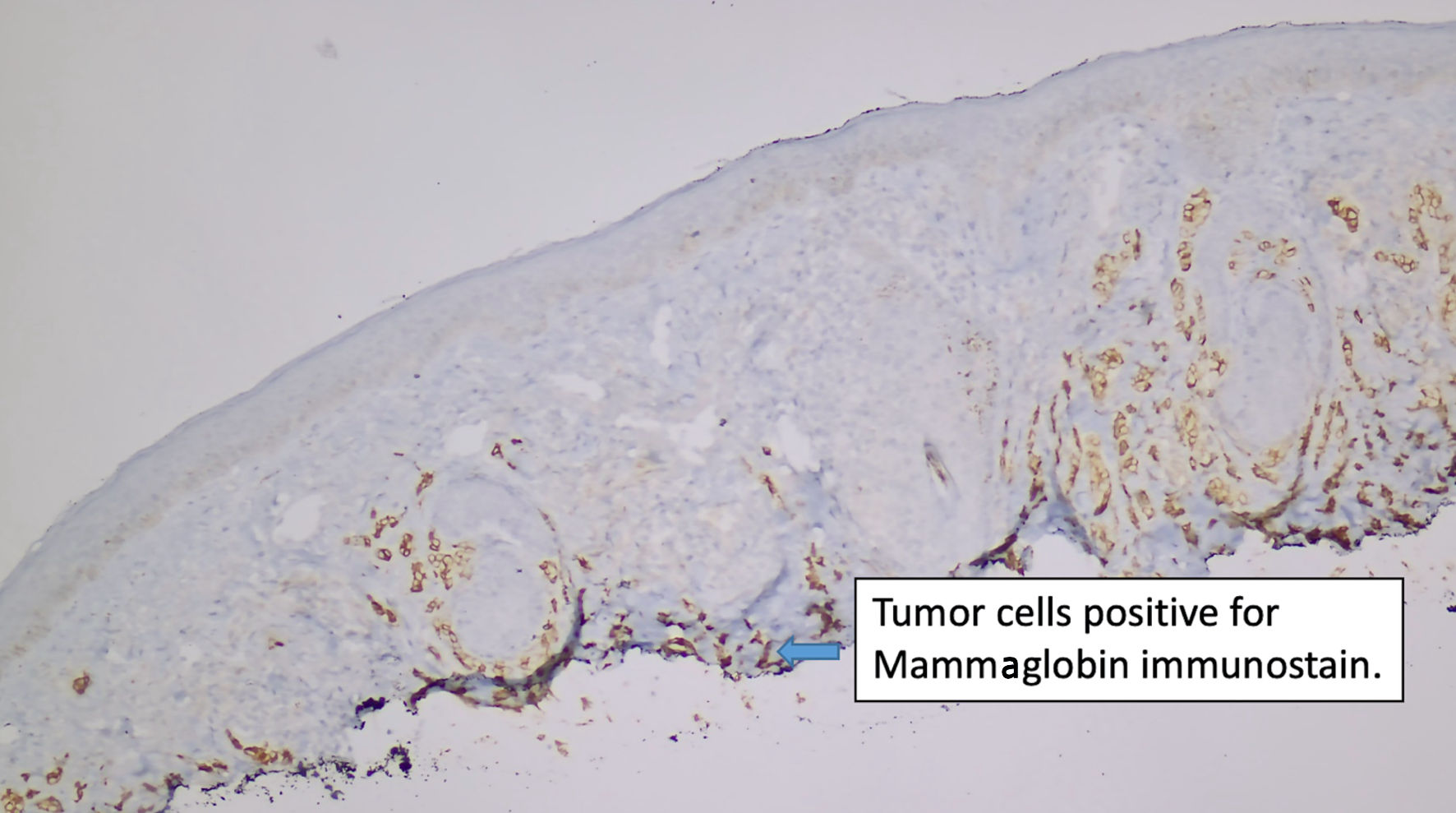

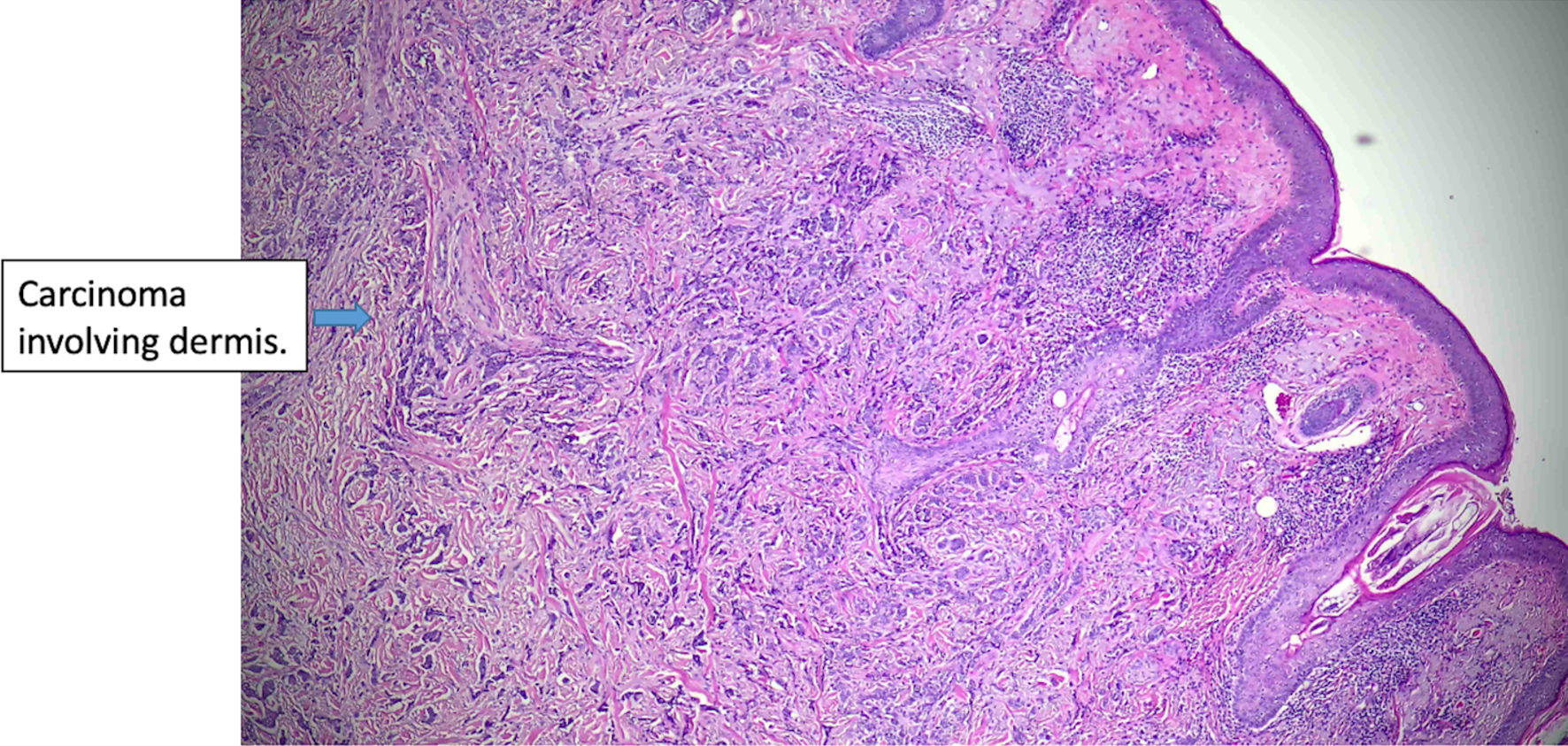

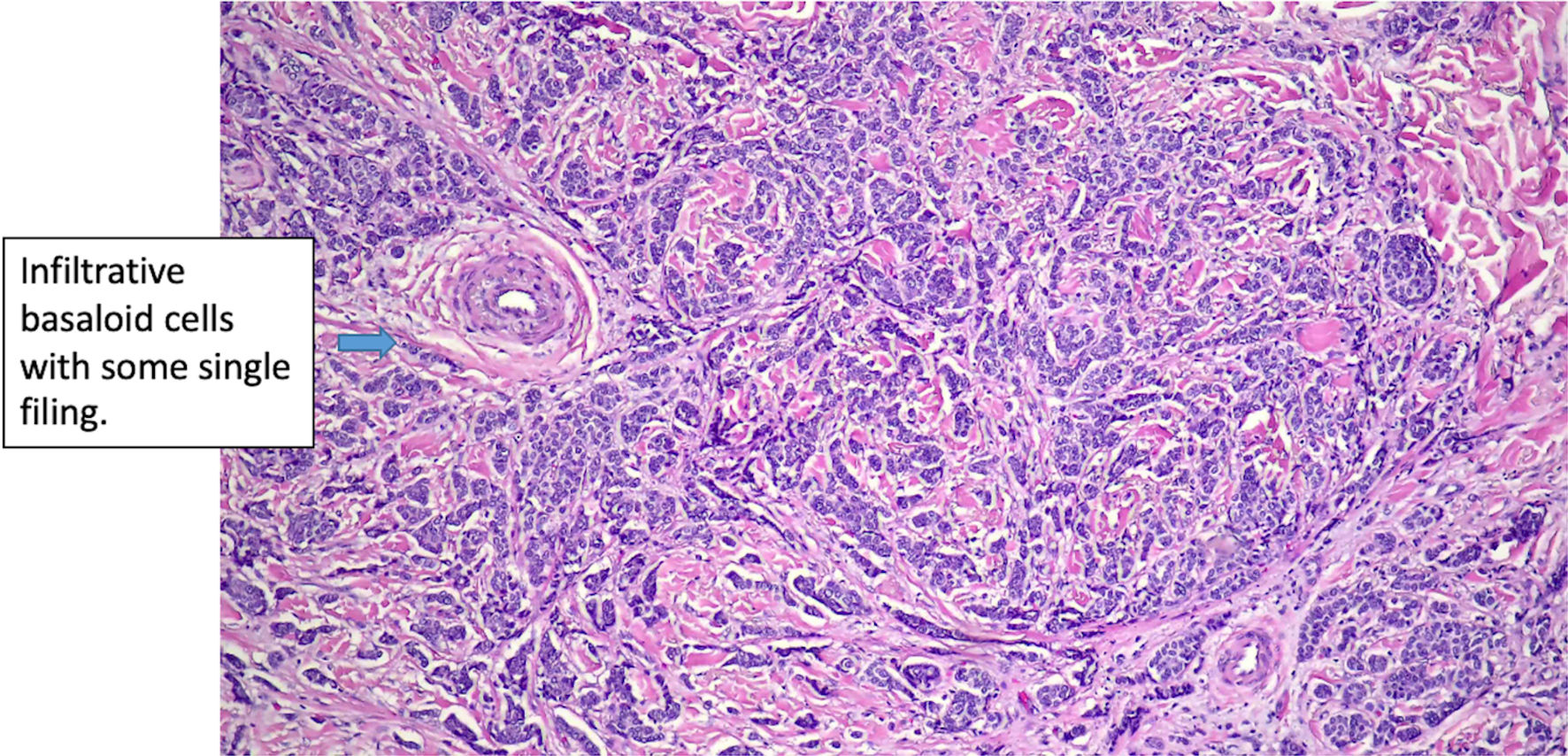

The patient is a 66-year-old female who presented to our facility in 2024 with a recurrent left lower lip lesion characterized by throbbing pain and numbness. The lesion was initially found in 2017 and later recurred twice in 2020 and 2023, which was managed at another facility. The first surgery was done in 2017 with R0 resection. Pathology report of the recurrent lesion revealed invasive carcinoma, likely ductal carcinoma of the breast with neuroendocrine differentiation. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for CK7, GCDFP-15, mammaglobin, ER (99% strong), PR (99% strong), synaptophysin, and chromogranin, while negative for S100 and p63. E-cadherin showed a strong membranous pattern, suggestive of a ductal phenotype (Figs. 1-7). These findings indicated a primary ductal carcinoma of the breast. However, further investigation revealed no evidence of primary breast cancer. The recurrence of the lesion in 2020 led to another R0 resection, revealing a poorly differentiated carcinoma with potential neuroendocrine and sebaceous differentiation. The patient subsequently developed pain and contractures in the excision area, which prompted her to consult plastic surgery services in 2023, leading to lip reconstruction and another biopsy. This procedure resulted in an R2 resection, with the finding of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with extensive perineural invasion evident at the margins. Accessory breast tissue was carefully examined, but no trace of it was found in any of the slides. The pathology slides were originally obtained from the outside facility and reviewed by a dermatopathologist and breast-specialized pathologist. In their interpretation, in the absence of breast lesions, a diagnosis of eccrine carcinoma was considered more appropriate - a known diagnostic pitfall.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Histologic features of eccrine carcinoma at the initial diagnosis. Basaloid cells are infiltrating the dermis. (original magnification × 100). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Immunostain for ER (original magnification × 100). ER: estrogen receptor. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Immunostain for PR (original magnification × 100). PR: progesterone receptor. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Immunostain for mammaglobin (original magnification × 100). |

Click for large image | Figure 5. Histologic features of eccrine cell carcinoma at excision. The carcinoma is infiltrative, largely involving the dermis (original magnification × 50). |

Click for large image | Figure 6. Histologic features of eccrine cell carcinoma at excision. (original magnification × 200). |

Click for large image | Figure 7. Histologic features of eccrine cell carcinoma at excision. Extensive perineural invasion. (original magnification × 400). |

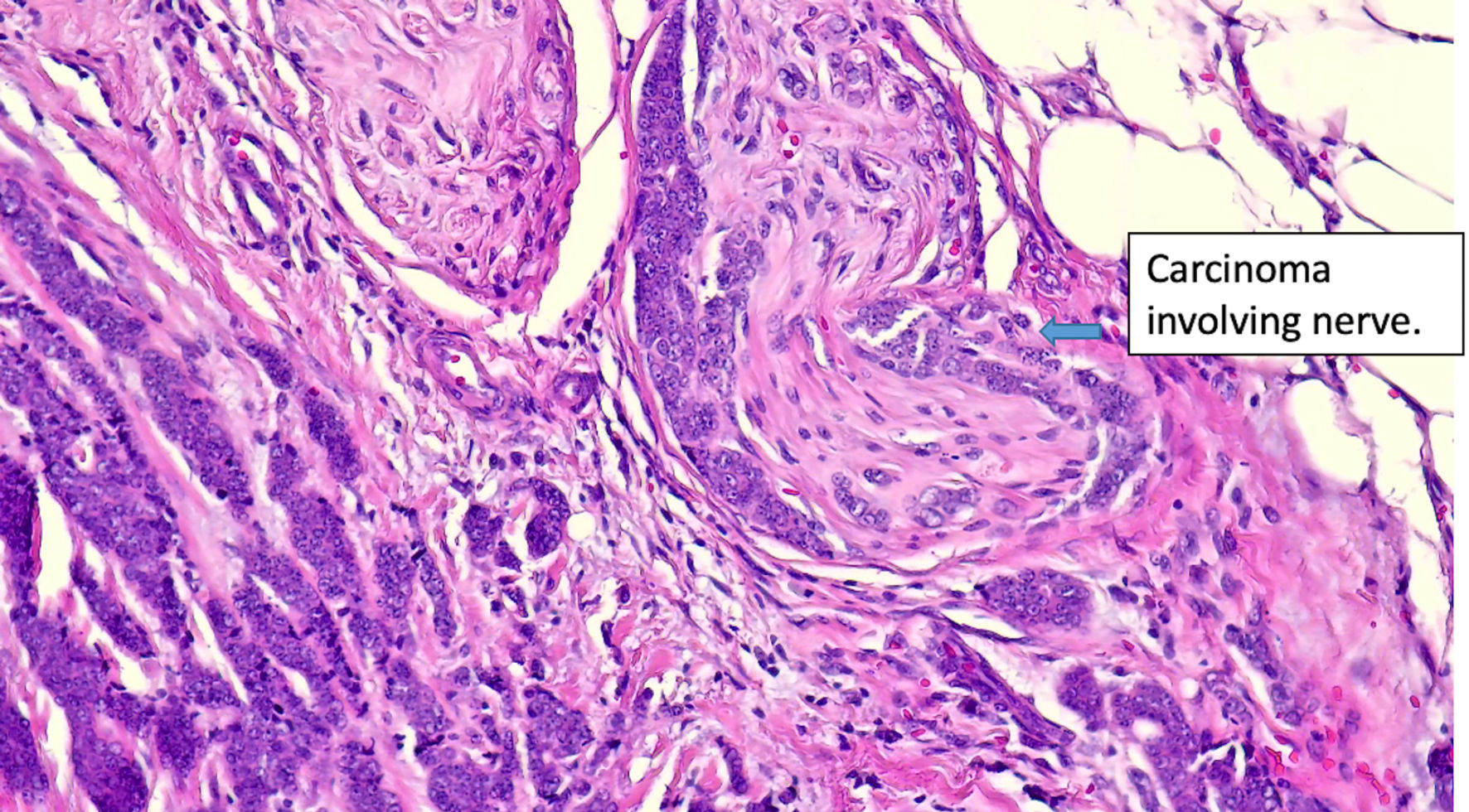

The positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) showed tracer-avid left anterior cervical, left internal mammary arterial chain, and pulmonary mediastinal/hilar lymphadenopathy, suggestive of metastatic disease. Additionally, a 6-mm tracer-avid nodule with maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 4.6, located within the left anterior facial soft tissues adjacent to the zygomatic bone, raised concern for neoplastic involvement. There was no evidence of a tracer-avid primary malignant neoplasm in the breast, pharyngeal, glottic, lung, abdominal, or pelvic organs (Fig. 8). The patient denied any family history of breast cancer. In the absence of a prior history of breast cancer or a suspicious breast lesion clinically, a primary cutaneous carcinoma with mammary phenotype, specifically eccrine carcinoma, was suggested. Due to the R2 resection, the patient was initially offered treatment with cisplatin as a radiation sensitizer followed by radiotherapy. She fully understood the prognosis, as well as the benefits and risks associated with the treatment options, but ultimately declined chemotherapy and radiotherapy. She came to our hospital for a second opinion and commenced treatment with letrozole and ribociclib, a regimen extrapolated from receptor-positive breast cancer therapy. The patient has been on letrozole and ribociclib for 10 months. She developed a rash on her arms and legs, and mild leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 2.9 × 103/µL, which resolved 2 months later. Otherwise, she tolerates the treatment well without signs of disease progression. The follow-up PET/CT after 6 months revealed decreased left facial subcutaneous nodule adjacent to the zygomatic bone, measuring 5 × 3 mm with an SUVmax of 1.5. There was resolution of abnormal tracer uptake in the left internal mammary arterial chain lymph node, with stable tracer uptake of mediastinal lymph nodes.

Click for large image | Figure 8. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) scan of the whole body demonstrates increased FDG avidity in (a) left level 1 lymph node, (b) left level 2 lymph node, (c) left internal mammary lymph node, (d) mediastinal/paratracheal lymph node, and (e) left malar soft-tissue nodule (yellow arrows), concerning for metastatic disease. (f) No evidence of increased FDG avidity within the breast tissues to suggest neoplastic disease. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Our case demonstrated the careful differential diagnosis of eccrine carcinoma, highlighting the importance of clinical and imaging correlation in ruling out potential primary or metastatic breast cancer. In addition to conventional treatments of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, our case introduces hormone therapy with letrozole and ribociclib as a novel option, with its tolerable adverse effects and promising efficacy.

Eccrine carcinoma remains an understudied malignant subtype, usually presenting as a solitary lesion in the head and neck region [13]. Histopathologically, these lesions can emulate metastatic breast cancer. However, the literature is still limited to a few case reports describing isolated skin lesions that mimic breast cancer [13-17]. One previous case report described two cases: one with a scalp lesion and one with a right axillary skin lesion. Pathology findings revealed “mucinous carcinoma consistent with a metastasis from primary breast cancer,” despite the absence of primary breast lesions, which was similar to our case. The patients were diagnosed with eccrine carcinoma, and one underwent wide local excision, while the other patient chose to observe the condition [14]. Another case report presented a patient with a history of breast cancer who developed a new scalp lesion, raising concerns about cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma. However, there was no clear evidence of breast cancer recurrence. The patient was ultimately diagnosed with eccrine carcinoma [13]. Both case reports highlight the challenge of differentiating eccrine carcinoma from breast cancer.

The human breast is a modified apocrine gland comprised of parenchymal and stromal tissues covered by skin. Given this common origin, differentiating adnexal carcinomas from metastatic breast cancer can be challenging. Immunohistochemistry has a limited role. Studies attempting to distinguish between the two were not successful. They concluded that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression might favor the diagnosis of eccrine carcinoma, while ER, PR, and anti-gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (BRST-2) are not reliable markers for distinguishing metastatic breast carcinoma from eccrine carcinoma [18, 19]. Other studies revealed that p63, CD117 and basal cytokeratins (CK5, CK14, and CK17) were more frequently found in eccrine carcinoma and might have very high specificity, while mammaglobin was more commonly expressed in metastatic breast cancer [20, 21]. Additionally, Mentrikoski et al suggested that p63 and CK5/6 are specific determinants for sweat gland carcinoma. However, they noted that if these markers are negative, it is difficult to make a definitive diagnosis, and clinical presentation may need to be considered for diagnosis [10]. In our case, the pathology revealed negative p63 and CK5/6 but positive CK7 and mammaglobin, which made the diagnosis challenging and required consideration of the clinical presentation of the lip lesion.

Lookingbill et al documented a cohort of patients exhibiting cutaneous manifestations as the primary indicator of internal malignancy. Among these, breast cancer emerged as the most prevalent malignancy to manifest through cutaneous involvement. However, most of the cases involved local skin involvement, with only five out of 237 cases presenting with remote skin metastasis [22]. Another possible differential would be accessory breast cancer. Accessory breast cancer can be found anywhere along the thoracoabdominal region of the embryologic mammary streak and is rarely found on the face [23]. Several case reports have documented axillary accessory breast cancer, but none mentioned facial or lip lesions [24-26]. Another recent study concluded that differentiating primary cutaneous adnexal adenocarcinoma from breast cancer metastasis still relies on the correlation of clinical pictures, pathology, and imaging findings [27]. In our case, imaging confirmed the absence of a primary breast cancer lesion, reducing the likelihood of metastatic breast cancer. Additionally, since the lip is not part of accessory breast tissue, the possibility of accessory breast cancer was also ruled out. The local recurrence of the lip lesion, a characteristic feature of eccrine carcinoma, further supported this diagnosis. Based on the clinical presentation and pathology findings, the patient was ultimately diagnosed with eccrine carcinoma by a multidisciplinary team.

There is no established treatment for malignant sweat gland cancer due to its rarity. The primary treatment for localized eccrine carcinoma is wide excision [6, 17, 28, 29]. Mohs micrographic surgery was reported to be a treatment option for eccrine carcinoma [30]. Localized lesions can also be treated with radiotherapy [31]. In cases of metastatic disease, chemotherapy, and radiation are the primary methods of treatment [32-34]. Previous case reports have suggested that hormone receptor-positive eccrine carcinoma may respond to hormone therapy, such as tamoxifen and letrozole [5, 35]. Schroder et al demonstrated successful treatment of eccrine carcinoma with adjuvant tamoxifen, with patients achieving complete remission for at least 3 years. They noted that although ER and PR cannot differentiate eccrine cancer from breast cancer, the markers offer a strong therapeutic target [35]. In our case, the patient underwent excision twice but eventually experienced recurrence with imaging evidence suggestive of metastatic disease. Consequently, systemic treatment was required. In light of the toxicity associated with chemotherapy and patient preference, hormone therapy targeting the positive receptor became a viable strategy. Our patient was thus started on a regimen of letrozole and ribociclib, based on her ER- and PR-positive and HER2-negative status. The addition of ribociclib to letrozole has demonstrated promising results in the treatment of hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. The MONALEESA-2 trial reported a 12-month increase in overall survival compared to letrozole plus placebo [36]. The treatment is generally well-tolerated, with the most common adverse events of neutropenia, nausea, and fatigue [37]. However, evidence supporting the efficacy of this combination in eccrine tumors remains limited, with only a few case reports documenting the successful use of anti-hormonal therapy in ER- and PR-positive eccrine tumors [38].

We extrapolated the treatment effect from breast cancer into eccrine carcinoma, given the fact that the pathology report revealed ER and PR were strongly positive. As a result, instead of using the monotherapy of tamoxifen or letrozole as previous case reports suggested, we decided to start on ribociclib and letrozole. More evidence is needed to support the use of these regimens in hormone receptor-positive eccrine carcinomas. Our patient tolerated the treatment well but developed leukopenia, which resolved in 2 months. There are limited data on the duration of the hormone therapy in eccrine carcinoma. Lifelong follow-up might be required for the patient to follow up on the efficacy and safety of the treatment. This case also highlights the importance of patient-centered care, particularly in tailoring treatment options for rare cancers. By engaging the patient in shared decision-making, we prioritized her preferences while addressing the unique challenges of managing metastatic eccrine carcinoma. Further research is needed to establish clear guidelines for the duration of hormone therapy and to compare its efficacy with chemotherapy in such rare malignancies.

Our study presented a case of eccrine carcinoma diagnosed through clinical evaluation, pathological findings, and imaging results. The patient was treated with hormone therapy, leveraging prior studies and the established use of letrozole and ribociclib in ER- and PR-positive breast cancer. Despite our efforts to make the manuscript as comprehensive as possible, this study has several limitations. The patient presented to our institution for a second opinion following surgical resection at another facility. Thus, we do not have photographs of the patient’s original lesion. Our diagnostic evaluation was based on the clinical characteristics of the patient, our pathology reports, PET/CT imaging, and multidisciplinary team discussion. Despite these constraints, this case highlights essential insights into the diagnostic challenges and therapeutic potential of hormone therapy in managing hormone receptor-positive eccrine carcinoma. Given the diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties of eccrine carcinoma, future research should aim to identify potential molecular targets that could serve as diagnostic and treatment biomarkers. Additionally, larger-scale clinical studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of hormonal therapies in eccrine carcinoma are crucial to validate their therapeutic potential and establish standardized treatment protocols.

Conclusions

This case highlights the diagnostic challenges of eccrine carcinoma, given its diverse histopathological features and potential to mimic malignancies like breast cancer. Hormone therapy may be a potential option for hormone receptor-positive cases. Further research is essential to develop clearer diagnostic tools and standardized treatment protocols for this rare malignancy.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all individuals and institutions whose contributions facilitated the completion of this research.

Financial Disclosure

All authors declare that this research was conducted without any specific funding or financial support from any external organization. The article processing fee for this work is supported by the Department of Medicine at Englewood Hospital and Medical Center.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest to disclose. We affirm that this research was conducted in an unbiased manner, and any findings or conclusions presented in the paper are based solely on the merits of the research itself. There are no financial, personal, or professional relationships or circumstances that could potentially influence the objectivity or integrity of the research reported in this paper.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. All efforts have been made to protect patient identity, and no identifiable information has been disclosed.

Author Contributions

YHC, SI, SS, and MJ conceived the study. YHC and SI collected the data. YHC and KC prepared the images. YHC, AC, and MJ prepared the pathology results. YHC, SI, AYES, SS, and KC drafted the manuscript, with NR, AC, and MJ supervising the work. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Kaseb H, Babiker HM. Eccrine carcinoma. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2024.

- Larson K, Babiker HM, Kovoor A, Liau J, Eldersveld J, Elquza E. Oral capecitabine achieves response in metastatic eccrine carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2018;2018:7127048.

doi pubmed - Alsaad KO, Obaidat NA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms—part 1: an approach to tumours of the pilosebaceous unit. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(2):129-144.

doi pubmed - Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, Ghazarian D. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64(9):788-792.

doi pubmed - Brito M, Dionisio C, Ferreira JCM, Rosa M, Cunha F, Garcia M. Ductal eccrine carcinoma of the axilla: a diagnostic pitfall. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(2):239-242.

doi pubmed - Plachta I, Kleibert M, Czarnecka AM, Spalek M, Szumera-Cieckiewicz A, Rutkowski P. Current diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(10).

doi pubmed - Jarocki C, Kozlow J, Harms PW, Schmidt BM. Eccrine porocarcinoma: avoiding diagnostic delay. Foot Ankle Spec. 2020;13(5):415-419.

doi pubmed - Macagno N, Sohier P, Kervarrec T, Pissaloux D, Jullie ML, Cribier B, Battistella M. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(3).

doi pubmed - Crowson AN, Magro CM, Mihm MC. Malignant adnexal neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(Suppl 2):S93-S126.

doi pubmed - Mentrikoski MJ, Wick MR. Immunohistochemical distinction of primary sweat gland carcinoma and metastatic breast carcinoma: can it always be accomplished reliably? Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143(3):430-436.

doi pubmed - National Comprehensive Cancer Network Head and Neck Cancers, version 1 2025 (Last Access Dec 29). https://www.nccnorg/guidelines/category_1.

- Geiger JL, Ismaila N, Beadle B, Caudell JJ, Chau N, Deschler D, Glastonbury C, et al. Management of salivary gland malignancy: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(17):1909-1941.

doi pubmed - Moonen H, Koot RAC, Hoven-Gondrie ML. [Eccrine carcinoma: a diagnostic pitfall]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2020;164.

pubmed - Merrill AL, Smith SM, Peters SB, Agnese DM. Eccrine carcinoma masquerading as metastatic breast cancer. Breast J. 2020;26(2):284-286.

doi pubmed - Bun S, Goto K, Oishi T, Kiyohara Y, Tsutsumida A, Yoshikawa S. Sweat gland carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation of the areola as a potential clinicopathologic mimicker of male breast carcinoma and syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44(11):850-854.

doi pubmed - Wu J, Chen H, Dong J, Cao Y, Li W, Zhang F, Zeng X. Axillary masses as clinical manifestations of male sweat gland carcinoma associated with extramammary Paget's disease and accessory breast carcinoma: two cases report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20(1):109.

doi pubmed - Park BW, Kim SI, Lee KS, Yang WI. Ductal eccrine carcinoma presenting as a Paget's disease-like lesion of the breast. Breast J. 2001;7(5):358-362.

doi pubmed - Wallace ML, Longacre TA, Smoller BR. Estrogen and progesterone receptors and anti-gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (BRST-2) fail to distinguish metastatic breast carcinoma from eccrine neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 1995;8(9):897-901.

pubmed - Busam KJ, Tan LK, Granter SR, Kohler S, Junkins-Hopkins J, Berwick M, Rosen PP. Epidermal growth factor, estrogen, and progesterone receptor expression in primary sweat gland carcinomas and primary and metastatic mammary carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 1999;12(8):786-793.

pubmed - Rollins-Raval M, Chivukula M, Tseng GC, Jukic D, Dabbs DJ. An immunohistochemical panel to differentiate metastatic breast carcinoma to skin from primary sweat gland carcinomas with a review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135(8):975-983.

doi pubmed - Valencia-Guerrero A, Dresser K, Cornejo KM. Utility of immunohistochemistry in distinguishing primary adnexal carcinoma from metastatic breast carcinoma to skin and squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40(6):389-396.

doi pubmed - Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. A retrospective study of 7316 cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22(1):19-26.

doi pubmed - Patel PP, Ibrahim AM, Zhang J, Nguyen JT, Lin SJ, Lee BT. Accessory breast tissue. Eplasty. 2012;12:ic5.

pubmed - Ichihashi K, Adachi A, Sawada Y. Accessory breast cancer: A case report and literature review of ultrasonographic findings. Australas J Dermatol. 2023;64(4):e384-e385.

doi pubmed - Addae JK, Genuit T, Colletta J, Schilling K. Case of second primary breast cancer in ectopic breast tissue and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(4).

doi pubmed - Hatada T, Ishii H, Sai K, Ichii S, Okada K, Utsunomiya J. Accessory breast cancer: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Tumori. 1998;84(5):603-605.

doi pubmed - Babkowski N, Savitz-Vogel G, Radoncipi AM, Stratton J, Savitz D, Volpicelli ER. Primary cutaneous adnexal adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified versus metastatic breast carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. JAAD Case Rep. 2024;51:41-44.

doi pubmed - Frouin E, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Balme B, Cavelier-Balloy B, Zimmermann U, Ortonne N, Carlotti A, et al. Anatomoclinical study of 30 cases of sclerosing sweat duct carcinomas (microcystic adnexal carcinoma, syringomatous carcinoma and squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(10):1978-1994.

doi pubmed - Moy RL, Rivkin JE, Lee H, Brooks WS, Zitelli JA. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24(5 Pt 2):857-860.

doi pubmed - Camayo TV, Dane A. Mohs Micrographic Surgery of Uncommon Tumors (Angiosarcoma, Eccrine, Paget, and Merkel Cell). In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. 2025.

pubmed - Larnaudie A, Giraud P, Naessens C, Stefan D, Clavere P, Balosso J. Radiotherapy of skin adnexal carcinoma. Cancer Radiother. 2023;27(4):349-354.

doi pubmed - Guerrissi JO, Quiroga JP. Adnexal carcinomas of the head and neck. Indian J Plast Surg. 2008;41(2):229-234.

doi pubmed - Ballardini P, Margutti G, Pedriali M, Querzoli P. Metastatic syringoid eccrine carcinoma of the nipple. Int Med Case Rep J. 2012;5:45-48.

doi pubmed - Nishizawa A, Nakanishi Y, Sasajima Y, Yamazaki N, Yamamoto A. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma with apparently aggressive transformation: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(10):1218-1221.

doi pubmed - Schroder U, Dries V, Klussmann JP, Wittekindt C, Eckel HE. Successful adjuvant tamoxifen therapy for estrogen receptor-positive metastasizing sweat gland adenocarcinoma: need for a clinical trial? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):242-244.

doi pubmed - Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, Yap YS, Sonke GS, Hart L, Campone M, et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(10):942-950.

doi pubmed - O'Shaughnessy J, Petrakova K, Sonke GS, Conte P, Arteaga CL, Cameron DA, Hart LL, et al. Ribociclib plus letrozole versus letrozole alone in patients with de novo HR+, HER2- advanced breast cancer in the randomized MONALEESA-2 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;168(1):127-134.

doi pubmed - Kalakonda AJM, Mahajan A, Chow S, Olsson-Brown AC, Sacco JJ. Oestrogen receptor positive metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report and review of anti-oestrogen therapy in rare cancers. Case Rep Oncol. 2024;17(1):497-503.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.