| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, October 2025, pages 000-000

Ocular Syphilis in an Immunocompetent Patient: Through the Lens

Sravani Kamatama, c , Sandeep Guntukub

aDepartment of Adult Hospitalist Services, OSF Saint Francis Hospital, Peoria, IL, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, Mamata Medical College, Khammam, Telangana, India

cCorresponding Author: Sravani Kamatam, Department of Adult Hospitalist services, OSF Saint Francis Hospital, Peoria, IL, USA

Manuscript submitted August 14, 2025, accepted September 23, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: Ocular Syphilis in an Immunocompetent Patient

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5193

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Ocular manifestations of syphilis can occur at any stage of the disease and present with a wide range of clinical features. If left untreated, they carry a high risk of permanent vision loss. Although syphilis mainly affects individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive and other immunocompromised individuals, it can also present in immunocompetent individuals. A 61-year-old immunocompetent male presented with blurry vision and associated central vision loss in the left eye. Initial ophthalmologic evaluation revealed bilateral optic-disc swelling and serological tests positive for syphilis, with rapid plasma reagin (RPR) of 1:128 and positive immunoglobulin (Ig)G/IgM, confirming ocular syphilis. The patient was started on intravenous (IV) penicillin G for 14 days and required a prolonged course along with oral steroids due to persistent syphilitic uveitis. This case report highlights the importance of maintaining a low threshold for syphilis screening in patients with unexplained vision loss, regardless of their HIV status. Timely diagnosis and intervention are critical to avoid misdiagnosis and prevent irreversible visual sequelae.

Keywords: Syphilis; Ocular syphilis; Vision loss; Neurosyphilis; Uveitis

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease caused by Treponema pallidum. The primary mode of transmission of syphilis is through sexual contact, and the risk is influenced by factors such as the frequency of sexual activity, type of sexual contact (e.g., penile-vaginal, penile-anal, or penile-oral), stage of syphilis in the source partner, susceptibility of the exposed individual, and whether condoms are used. However, it can also be transmitted through blood transfusions, maternal to fetal transmission, and rarely direct skin-to-infectious lesion contact. It progresses through four different stages: primary, secondary, tertiary, and latent syphilis if left untreated. Characteristic primary syphilis presents as an isolated, non-tender genital chancre. Some patients may also present with non-genital lymph node enlargement which usually resolves without treatment; therefore, diagnosis in the primary stage of syphilis can be challenging. When not treated, primary syphilis can progress into secondary and tertiary stages involving other organs. Infection can progress to neurosyphilis at any given stage after the initial infection. Likewise, ocular syphilis, a manifestation of neurosyphilis, can occur at any stage. Ocular infection and associated inflammation are grouped under the term ocular syphilis. Ocular syphilis contributed to 10-15% of blindness in the United States before the antibiotic era, and there has been an increase in the number of ocular syphilis cases in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) individuals. Among ocular syphilis subtypes, posterior uveitis and panuveitis are the most common manifestations [1].

Multiple studies have shown that syphilis is reemerging in developed countries, with parallel increase in ocular manifestations. With the increase in the expansion of susceptible populations, including homosexual and HIV infections, the incidence of syphilis went up to 17.3% since 2021 [2]. Risk factors for developing neurosyphilis include being male, men who have sex with men (MSM), age greater than 45 years, HIV infection, drug use disorder, lack of antisyphilitic therapy, reinfection, and patients with serofast state. The national rates of primary and secondary syphilis have increased among women concurrently with an increase in cases among men who have sex with women (MSW), reflecting an expanding heterosexual syphilis epidemic in the United States. MSM are disproportionately impacted by primary and secondary syphilis, with a high rate of HIV coinfection. Notably, 36.4% of MSM diagnosed with primary and secondary syphilis are also diagnosed with HIV [2]. We are presenting a case of ocular syphilis in a non-HIV/immunocompetent patient who presented with vision loss as the initial presenting feature.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 61-year-old male with a past medical history of essential hypertension and type II diabetes mellitus initially presented to an ophthalmologist’s office with blurry vision in the left eye. He reported a central dark spot with preserved peripheral vision. At the ophthalmologist’s office, he denied eye pain or pain with eye movement. The initial eye exam showed normal intraocular pressure but revealed bilateral optic nerve swelling, and he was sent to the emergency department (ED) for further evaluation. Patient denied any rash or any other symptoms like fever, chills, abdominal pain, or any recent illness or sick contacts. He reported that he is not sexually active but has a history of multiple sexual partners and unprotected intercourse. His initial general physical examination was unremarkable. The patient had normal bilateral extraocular eye movements, a visual acuity of 20/40 in the right eye, and in the left eye, he had the ability to count fingers on the examiner’s hand at 3 ft. He had central scotoma on the left eye. No other neurological deficits were noted on examination.

Diagnosis

In the ED, he was hemodynamically stable, and the initial workup with complete blood count and complete metabolic profile was normal. A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) head was ordered on admission to rule out stroke or any other infectious cause of the vision loss. It showed a small area of indeterminate decreased density in the right insula, which would not explain his symptoms, but was otherwise normal. A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast was ordered, which showed no acute findings. There was a concern for meningitis, and a lumbar puncture was done. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) opening pressure was normal at 16 cm of water. CSF white blood cell (WBC) count and protein were high, and the gram stain was negative. He was initially started on intravenous (IV) acyclovir and was stopped once CSF herpes simplex virus (HSV) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was negative, and the CSF meningitis panel was negative. His C-reactive protein was normal, but his erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was mildly elevated at 28 mm/h (normal value of ESR 0 - 15 mm/h). Other infectious workup including HIV panel, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcal infection, coccidiomycosis, tuberculosis, and Lyme serology, was negative. Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and sexually transmitted disease (STD) panels including Chlamydia, Neisseria and Trichomonas by nucleic acid amplification tests were ordered. Inflammatory workup with rheumatoid factor was also ordered and was negative. Given the progressive vision loss, he was transferred to our tertiary center for inpatient ophthalmology evaluation before the above test results became available. On arrival at our facility, he started having blurry vision in his right eye. Ophthalmology was consulted on arrival at the tertiary center, and the patient was started on Solu-Medrol 1 g on the first day for possible infectious, inflammatory, or autoimmune etiology. His RPR screen was positive, and syphilis immunoglobulin (Ig)G/IgM was positive, with an RPR titer of 1:128.

Treatment

He was diagnosed with ocular syphilis based on positive serological tests and was started on penicillin G IV 1 million units/h for a total of 14 days and was discharged to complete antibiotics with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line in place.

Follow-up and outcomes

Later, he had persistent syphilitic uveitis on follow-up outpatient ophthalmology visit, even after completion of antibiotics. He was started on benzathine penicillin 2.4 million units, which was given once a week for 2 weeks, and penicillin G 500 mg every 6 h for 2 weeks, along with prednisone 60 mg for 10 days, after which his symptoms improved. The need for partner testing and treatment was discussed with the patient. The patient’s vision was back to baseline, and there were no other complications.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Syphilis can mimic various ocular inflammatory conditions and may present solely with ocular symptoms. With its increasing prevalence and potential for serious complications, early recognition is critical. We report a case of ocular syphilis presenting as blurred vision, highlighting its nonspecific presentation and the need for high clinical suspicion to ensure prompt diagnosis and management.

Ocular syphilis can occur at any stage of the disease spectrum and can be manifested in different forms, including uveitis, retinitis, optic neuritis, and chorioretinitis, from a few weeks to months after primary infection. Ocular syphilis can be characterized under neurosyphilis, and ocular signs have led to the diagnosis of syphilis in up to 78% of patients [3]. In a retrospective study by Cheng et al, ocular signs were the primary complaint in 9.43% of patients, and 5.65% were diagnosed with ocular syphilis [4]. Most ocular syphilis cases have been observed in the tertiary stage, but nearly one-third have been reported during the primary and secondary stages. The mean time from the initial infection to ocular symptom manifestation was about 11 months, and 87.5% of patients developed ocular symptoms within 2 years [5].

Ocular syphilis is considered a manifestation of neurosyphilis, as Treponema pallidum invades the ocular tissue and retina, which is part of the central nervous system. The most common manifestation of ocular syphilis is syphilitic uveitis, which can be anterior, middle, posterior, or panuveitis. Syphilitic uveitis is noted to have an incidence of around 1-4% of ocular syphilis cases. Acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis (APPC) is a characteristic manifestation with one or more yellow-gray or yellow white squamous lesions on the retina. In a retrospective analysis of 17 cases of ocular syphilis by Xu et al, the most common manifestation of ocular syphilis was chorioretinitis, followed by optic neuropathy and oculomotor nerve palsy [6]. Syphilitic uveitis typically includes APPC, retinal necrosis and punctate inner retinopathy. Syphilis optic neuritis can present as perineuritis, retrobulbar optic neuritis or papillitis which is optic neuritis with disk swelling [7]. It can also present in several other ways, with optic disc edema as seen in our patient, along with vision loss, uveitis, retinitis, vitreous, and retinal vasculitis. Symptoms of ocular syphilis range from blurry vision to vision loss, with the posterior and panuveitis being the most common presentations. Given these broad range of clinical manifestations, nonspecific and fluctuating symptoms, syphilis is often referred to as the “great masquerader”. These characteristics, combined with its resemblance to other conditions, frequently result in delayed diagnosis, particularly in cases of ocular syphilis. A case report by Oliveira et al described a woman who presented with acute visual deterioration and was found to have uveitis on ophthalmologic evaluation. The diagnosis of syphilis was delayed by 2 months, ultimately resulting in permanent ocular damage and significant visual loss [8].

Ocular syphilis can closely mimic a range of inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, including intermediate uveitis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. It may also resemble other infectious etiologies such as toxoplasmosis and cytomegalovirus retinitis, as well as vasculitis disorders like tuberculosis and Behcet’s disease. Given this broad spectrum of differential diagnoses, ocular syphilis presents a significant diagnostic challenge, often leading to delays in appropriate treatment.

Other head and neck sites that are commonly involved in syphilis are oral cavity and oropharynx. The systematic review by Guarino et al highlighted the diagnostic challenges of oropharyngeal syphilis, which can mimic malignancies due to its highly variable presentation - paralleling our case and reinforcing the need for heightened clinical suspicion in atypical manifestations [9]. A case series by Culbert et al described three patients whose presentations mimicked head and neck carcinoma but were ultimately diagnosed with syphilis. This underscores the diagnostic complexity associated with syphilis and, considering its increasing prevalence alongside oropharyngeal carcinoma, highlights the importance of including syphilis in the differential diagnosis of similar clinical scenarios [10].

Given the co-occurrence of syphilis and HIV, there is a low index of suspicion for ocular syphilis in non-HIV patients presenting with decreased vision. In the past two decades, there has been a resurgence of syphilis in high-income countries, especially the United States, and has been attributed to multiple factors, including changes in sexual practices secondary to the successful elimination of HIV infectivity through treatment and susceptibility through chemoprophylaxis. In a retrospective study, Kim et al reviewed 39 HIV-negative patients and concluded that non-HIV-related ocular syphilis is uncommon [11]. However, timely treatment was associated with good clinical response and reduced disease-related morbidity.

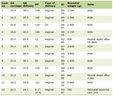

Presented below in Table 1 [6, 12-17] is a listing of ocular syphilis cases in HIV-negative patients published with respective stages at point of diagnosis in the years 2020 - 2024, indicating that ocular syphilis is not so rare anymore in HIV-negative patients.

Click to view | Table 1. Ocular Syphilis Cases in HIV-Negative Patients Published in the Years 2020 - 2024 |

Diagnosis of ocular syphilis is made concomitantly with symptoms and serological testing. Initial screening serological tests include RPR testing and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) testing [11]. Histopathological staining, darkfield microscopy, direct fluorescent antibody, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays can be used to directly detect Treponema pallidum, but it is not available widely, so serological testing is mainly used to diagnose syphilis.

The treatment of ocular syphilis is similar to neurosyphilis, with penicillin G, 18 - 24 million units recommended for 14 days. It can be administered as 3 - 4 million units every 4 h or as 24 million units as continuous infusion. Studies have shown that CSF abnormality in patients with ocular syphilis can be present and can have concomitant syphilitic meningitis, so it is beneficial but not recommended to get CSF analysis to start the treatment. Follow-up with CSF analysis is needed in patients with CSF abnormality to check for seroconversion 3 months after treatment and every 6 months after until the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) CSF becomes negative [18].

Conclusions

With worldwide resurgence in syphilis, the disease poses a serious public health concern. In the United States, syphilis incidence is increasing not only among traditional high-risk groups but also among non-HIV individuals. Loss of visual acuity should be considered as a warning sign of ocular syphilis in non-high-risk groups as well, and alert screening for syphilis. Maintaining a low threshold for suspicion, along with prompt diagnosis and treatment, is essential to prevent permanent vision loss.

Learning points

Accurate diagnosis is a critical first step in guiding patient management, initiating appropriate treatment, and preventing complications - whether to save sight or life. Early detection is especially crucial in cases of ocular syphilis, where inappropriate treatment with steroids is a common risk. Routine syphilis screening should be considered for patients presenting with reduced visual acuity or signs of optic neuropathy to avoid misdiagnosis and treatment delays.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This study did not receive any funding.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained verbally from the patient. No patient identifier is included in the case report.

Author Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Sravani Kamatam: writing the manuscript, reviewing the manuscript, researching literature and preparation of manuscript for final submission. Guntuku Sandeep: writing the initial draft for the manuscript and literature search.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings in the case report are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Jackson DA, McDonald R, Quilter LAS, Weinstock H, Torrone EA. Reported neurologic, ocular, and otic manifestations among syphilis cases-16 states, 2019. Sex Transm Dis. 2022;49(10):726-732.

doi pubmed - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2022 [Internet]. 2022 [cited May 1, 2024]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/overview.htm.

- Bazewicz M, Lhoir S, Makhoul D, Libois A, Van den Wijngaert S, Caspers L, Willermain F. Neurosyphilis cerebrospinal fluid findings in patients with ocular syphilis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(1):95-101.

doi pubmed - Cheng H, Zhu H, Shen G, Cheng Y, Gong J, Deng J. Ocular findings in neurosyphilis: a retrospective study from 2012 to 2022. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1472274.

doi pubmed - Tsuboi M, Nishijima T, Yashiro S, Teruya K, Kikuchi Y, Katai N, Gatanaga H, et al. Time to development of ocular syphilis after syphilis infection. J Infect Chemother. 2018;24(1):75-77.

doi pubmed - Xu Y, Li J, Xu Y, Xia W, Mo X, Feng M, He F, et al. Case report: Visual acuity loss as a warning sign of ocular syphilis: a retrospective analysis of 17 cases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1037712.

doi pubmed - Rasool N, Stefater JA, Eliott D, Cestari DM. Isolated presumed optic nerve gumma, a rare presentation of neurosyphilis. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2017;6:7-10.

doi pubmed - Oliveira R, Carvalho L, Ramos A, Cardoso MJ, Guimaraes JT. A rare case of syphilitic uveitis in a 61-year-old non-HIV woman. Porto Biomed J. 2024;9(1):242.

doi pubmed - Guarino P, Chiari F, Carosi C, Parruti G, Caporale CD, Presutti L, Molteni G. Description of clinical cases and available diagnostic tools of oropharyngeal syphilis: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):1252.

doi pubmed - Culbert AA, Israel AK, Ku J, Silver NL. The increasing problem of syphilis manifesting as head and neck cancer: a case series. Laryngoscope. 2024;134(1):236-239.

doi pubmed - Kim Y, Yu SY, Kwak HW. Non-human immunodeficiency virus-related ocular syphilis in a Korean population: clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2016;30(5):360-368.

doi pubmed - Nwaobi S, Ugoh AC, Iheme BC, Osadolor AO, Walker RK. Through the eyes: a case of ocular syphilis. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e48236.

doi pubmed - Paulraj S, Ashok Kumar P, Gambhir HS. Eyes as the window to syphilis: a rare case of ocular syphilis as the initial presentation of syphilis. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e6998.

doi pubmed - Kautz M, Kerbow C, Lee T, Kronmann KC, Dore M. A case series of ocular syphilis cases at military treatment facility from 2020 to 2021. Mil Med. 2024;189(1-2):e410-e413.

doi pubmed - Jahnke S, Sunderkotter C, Lange D, Wienrich R, Kreft B. Ocular syphilis - a case series of four patients. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19(7):987-991.

doi pubmed - Koksaldi S, Nazli A, Kaya M, Saatci AO. Never forget ocular syphilis: a case series from a single tertiary centre. Int J STD AIDS. 2023;34(11):817-822.

doi pubmed - Kabanovski A, Donaldson L, Jeeva-Patel T, Margolin EA. Optic disc edema in syphilis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2022;42(1):e173-e180.

doi pubmed - Marra CM, Maxwell CL, Tantalo L, Eaton M, Rompalo AM, Raines C, Stoner BP, et al. Normalization of cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities after neurosyphilis therapy: does HIV status matter? Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(7):1001-1006.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.