| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 12, December 2025, pages 475-486

Cecal Involvement of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Rare Extra-Nodal Presentation

Usama Sakhawata, e, Ahmed Shehadaha, Usman Mazharb, Miranda Gonzalezc, Fahad Malika, James Van Gurpd, Leslie Banka

aDepartment of Gastroenterology, United Health Services Hospitals, Binghamton, NY, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, Rawalpindi Medical College, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

cDepartment of Family Medicine, St. Joseph’s Health, Syracuse, NY, USA

dDepartment of Pathology, United Health Services Hospitals, Binghamton, NY, USA

eCorresponding Author: Usama Sakhawat, Department of Gastroenterology, United Health Services Hospitals, Binghamton, NY, USA

Manuscript submitted September 18, 2025, accepted October 25, 2025, published online November 22, 2025

Short title: Cecal Involvement of DLBCL

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5192

| Abstract | ▴Top |

We present the case of a 56-year-old male with cecal involvement of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), whose tumor was refractory to multiple chemotherapy regimens and ultimately resulted in significant local complications due to tumor erosion, leading to considerable morbidity. NHL is the most common hematologic cancer with many subtypes of disease, with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) being the most common. Extra-nodular presentation in the gastrointestinal tract is typical in many cases; however, the involvement of the colon is rare. This case details a patient with extra-nodal involvement of the cecum. The patient initially presented with an enlarging neck mass. This report highlights the importance of evaluating extra-nodular disease.

Keywords: Lymphoma; Colon; GI malignancies

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) represents a significant portion of hematologic malignancies, accounting for approximately 4% of all cancer diagnoses in the United States. The incidence of NHL has markedly increased, with a reported rise of 168% since 1975 [1]. NHL is characterized by its heterogeneity, comprising a multitude of subtypes, among which diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most prevalent which constitutes approximately 25% of all NHL cases in the United States [1]. Several risk factors have been identified in association with DLBCL, including prior exposure to radiation, obesity, tobacco use, and certain infectious agents such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8). A notable feature of NHL is its propensity for extra-nodal involvement, which occurs in up to 40% of patients [2], with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract being a common site for such manifestations [3, 4].

Primary GI lymphoma is uncommon, with colonic involvement seen in only ∼1.3% of all lymphoma cases, making primary colonic DLBCL, especially in the cecum, rare [5, 6]. In contrast, secondary colonic involvement from systemic DLBCL occurs in only 2-3% of cases, reflecting its rarity as an extranodal site [7]. Within the colon, the cecum is frequently identified as the primary site of involvement. The clinical presentation of colonic lymphoma can often be insidious, leading to delays in diagnosis due to the absence of early symptoms. This delay can result in significant complications, including disease progression, perforation, and an overall poorer prognosis. Patients with advanced-stage DLBCL have a favorable response to treatment, with more than 60% achieving remission or potential cure through the R-CHOP regimen, which combines rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone [8]. This case report details a patient diagnosed with aggressive DLBCL localized to the cecum, who initially presented with an enlarging neck mass.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Presentation and initial evaluation

A 56-year-old male with a past medical history of hypothyroidism due to Hashimoto thyroiditis presented to the office with a 6-week history of sore throat and an enlarging neck mass. The patient reported associated symptoms of throat swelling, odynophagia, and dysphagia, which significantly impacted his ability to swallow. Additionally, he experienced a notable 10-pound weight loss over this period and night sweats, raising concerns for a possible underlying malignancy. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck was performed, revealing a moderately enlarged thyroid gland with well-defined lesions bilaterally: a larger lesion on the right measuring 5.5 × 4.9 cm and a smaller lesion on the left measuring 3.0 × 1.8 cm. The imaging also demonstrated moderate prominence of the left tonsillar and peritonsillar soft tissues, accompanied by cervical lymphadenopathy and multiple prominent mediastinal lymph nodes indicative of possible lymphoproliferative disease.

Initial diagnosis and treatment of DLBCL

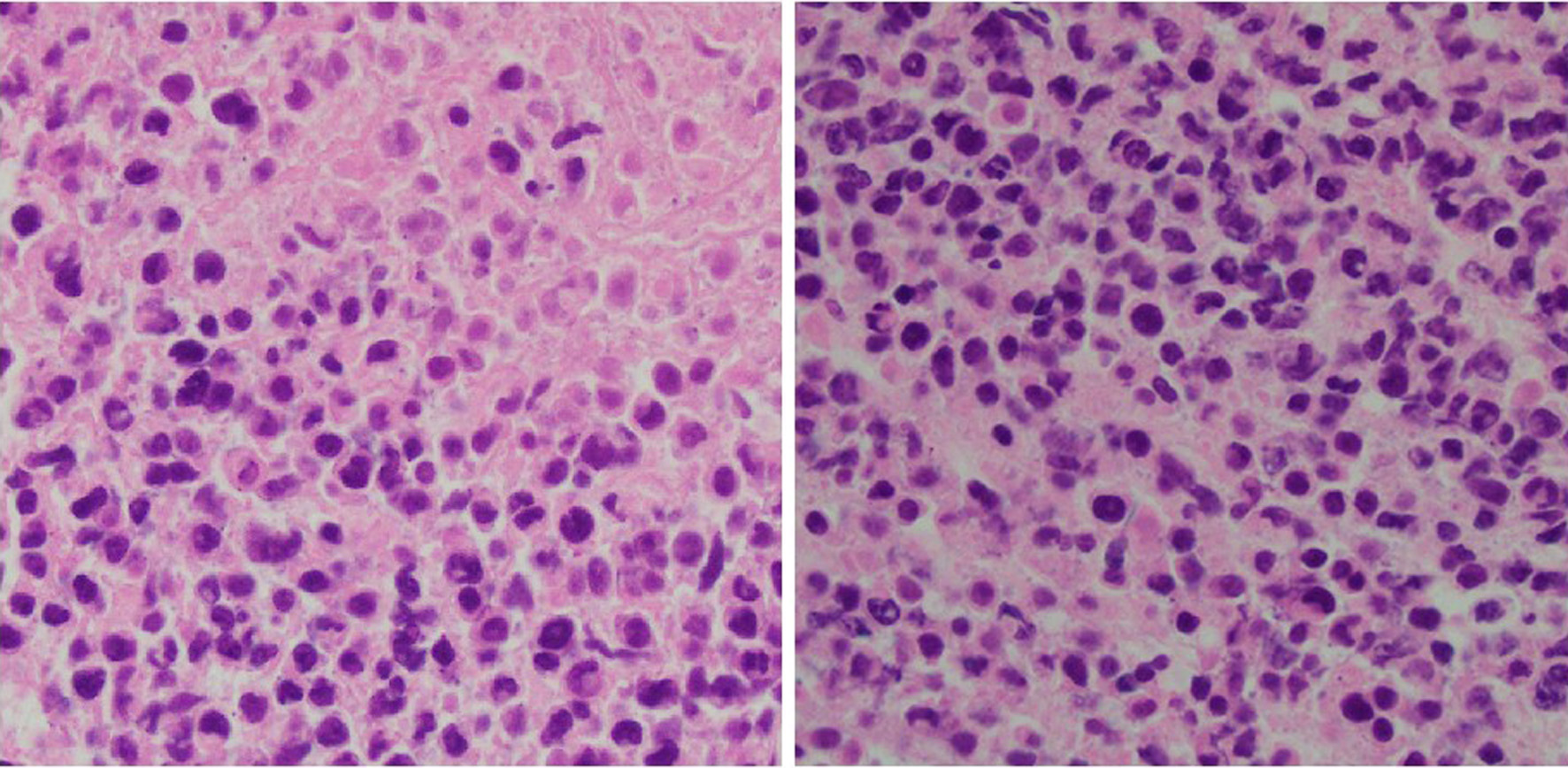

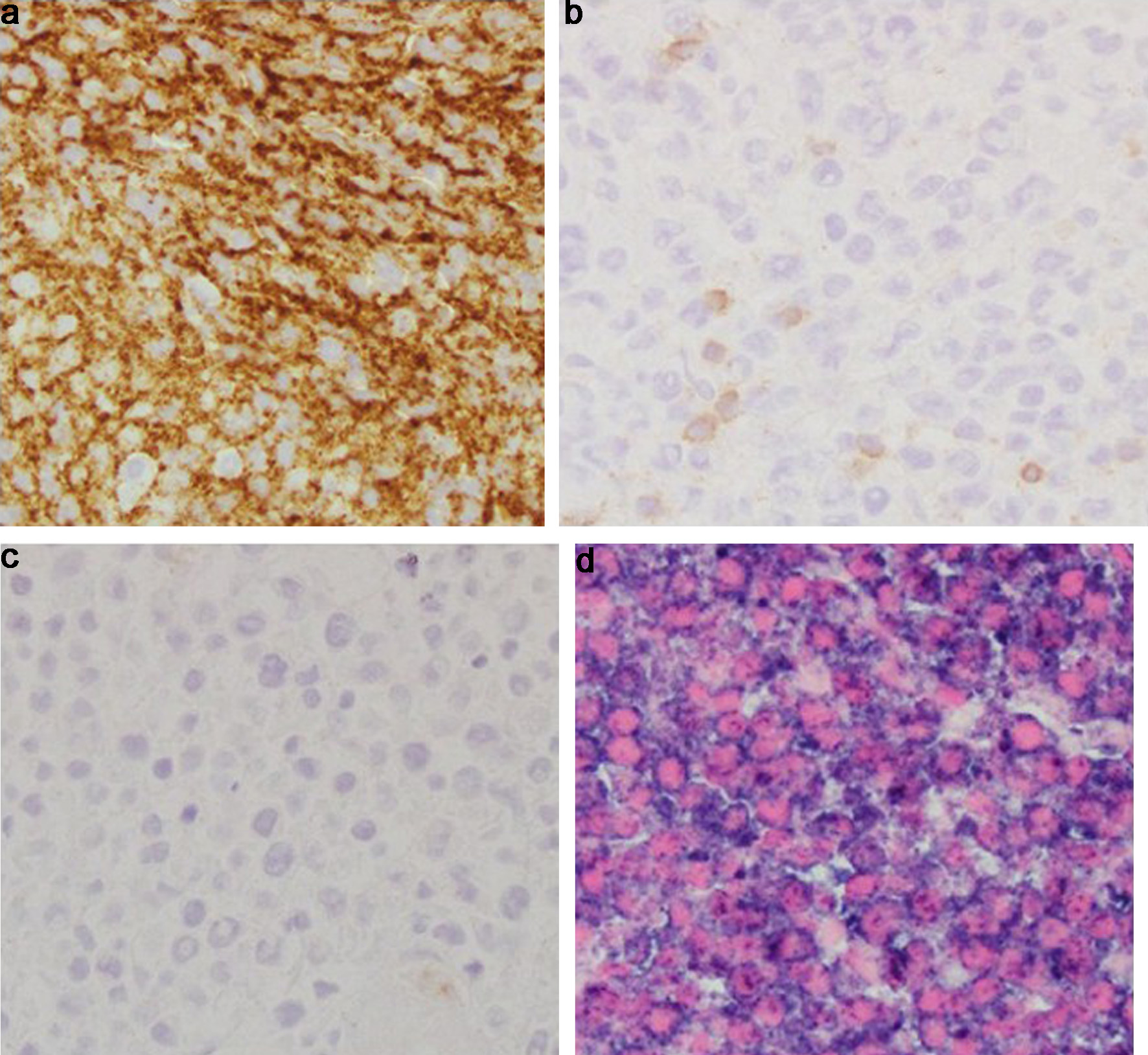

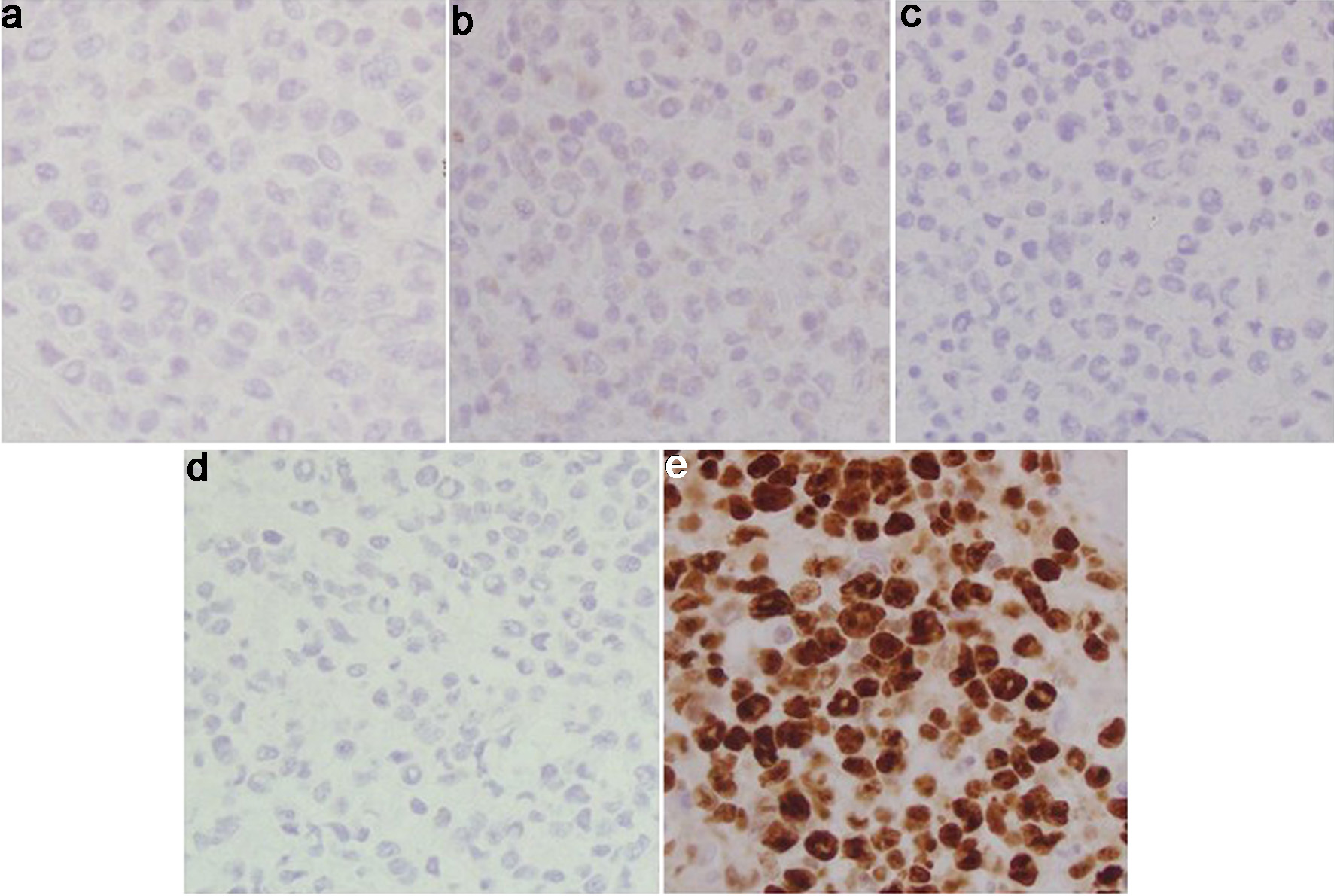

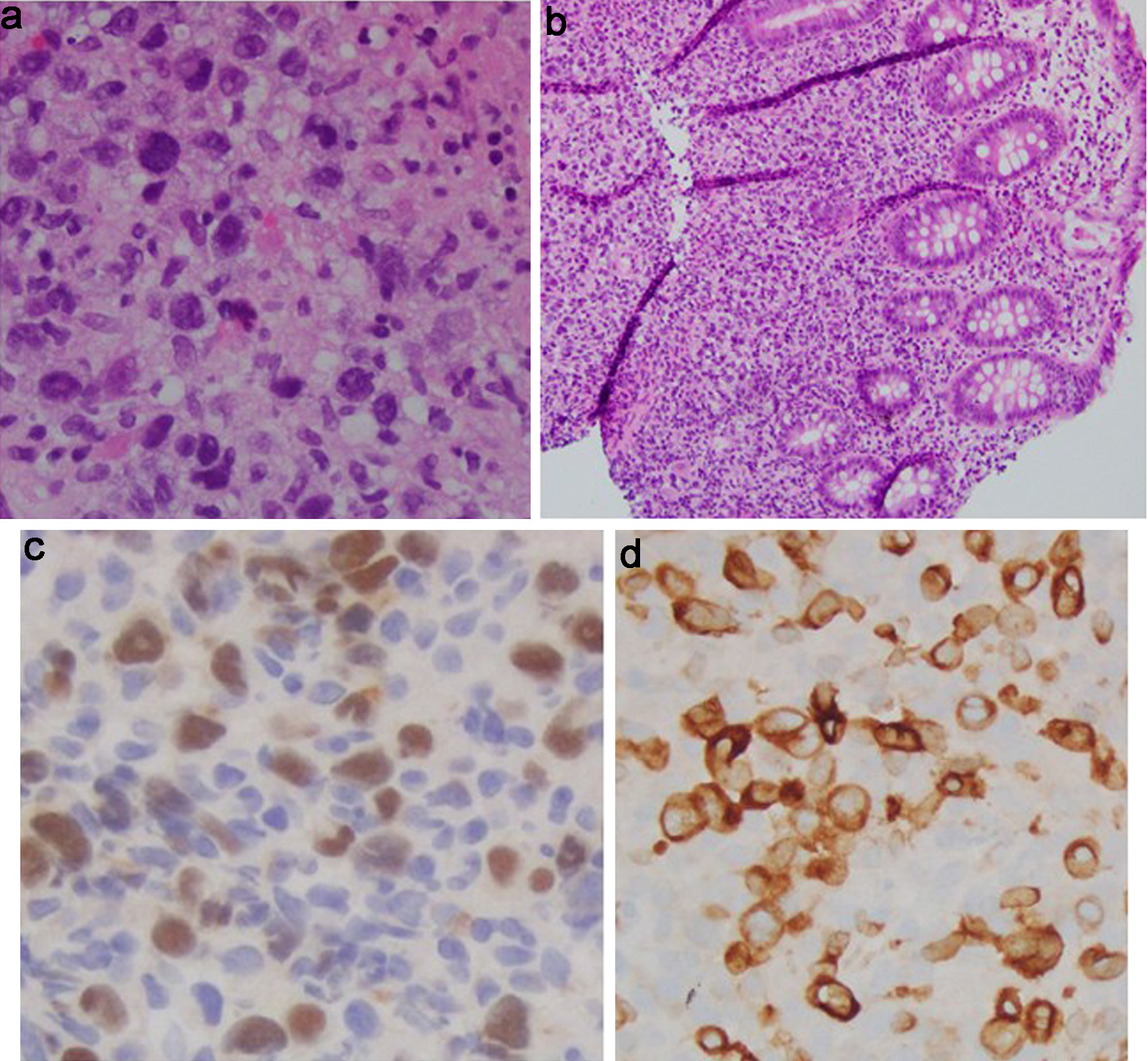

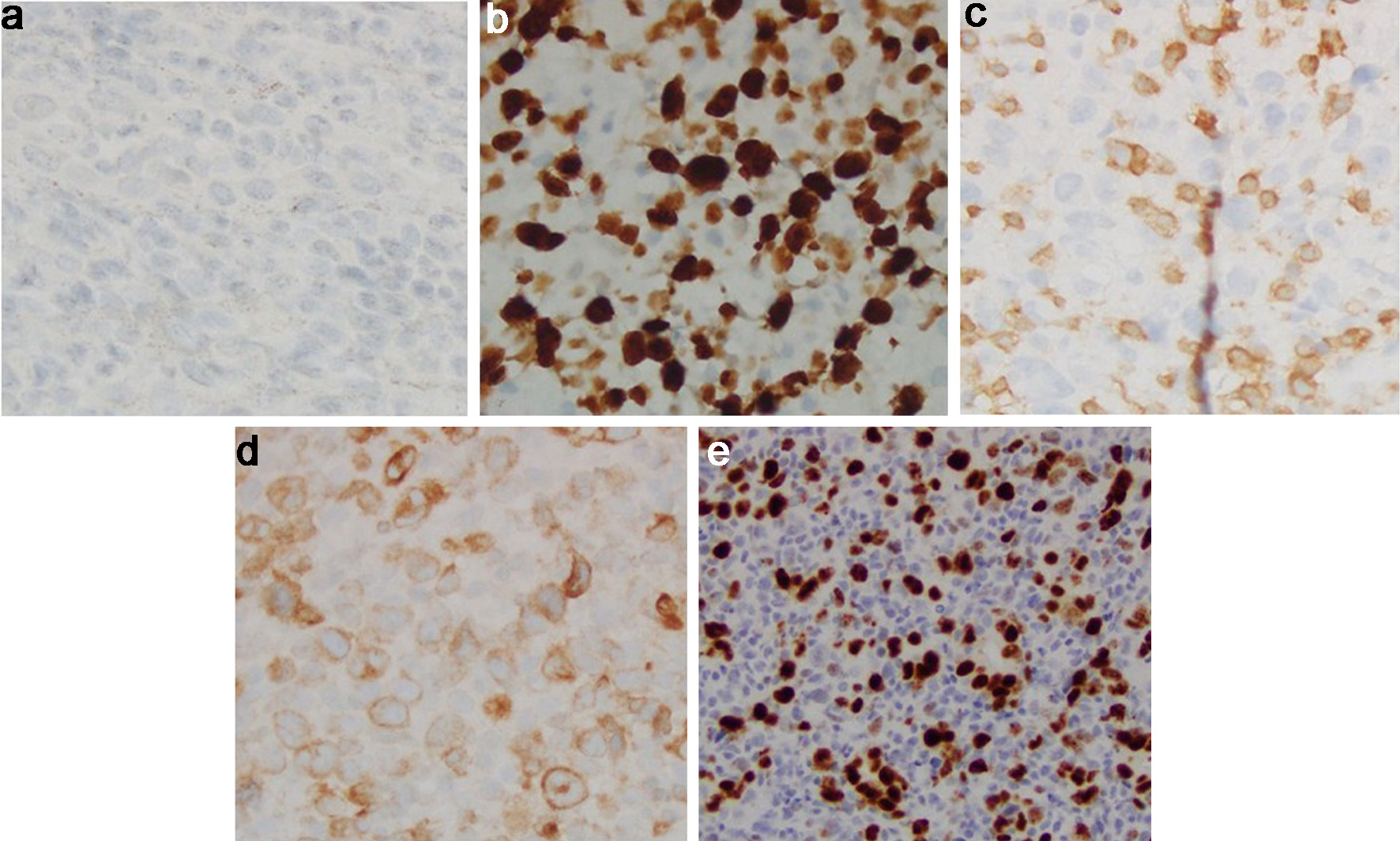

Subsequently, the patient underwent a biopsy of the left tonsillar mass. Histopathological examination showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate predominantly composed of small-to-medium-sized lymphocytes (Fig. 1). Immunophenotyping confirmed positivity for CD20 (Fig. 2a), a B-cell marker. Immunophenotyping and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) were negative for CD10, CD3, B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6), B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2), C-MYC and multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1) (Figs. 2b, c and 3a-d). Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA in situ hybridization (EBER-ISH) was positive (Fig. 2d). The Ki-67 proliferation index was notably high, ranging from 80% to 90%, which indicated a high-grade lymphoma (Fig. 3e). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with aggressive DLBCL. To assess the extent of the disease, a whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) scan combined with CT imaging was conducted.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Tonsil mass biopsy histology: high-grade lymphoid neoplasm with necrosis (H&E, × 40). H&E: hematoxylin and eosin. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Tonsil mass biopsy histology. (a) CD 20 immunostain (× 40): positive in the abnormal infiltrate, confirming B-cell lineage. (b) CD3 immunostain (× 40): negative in the neoplastic B cells. Admixed CD3+ small T cells. (c) CD10 immunostain (× 40): negative in the neoplastic B cells. (d) EBER-ISH (× 40): positive in the neoplastic B cells. EBER-ISH: Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA in situ hybridization. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Tonsil mass biopsy histology. (a) BCL6 immunostain (× 40): negative in the neoplastic B cells. (b) BCL2 immunostain (× 40): negative in the neoplastic B cells. (c) C-MYC immunostain (× 40): negative in the neoplastic B cells. (d) MUM1 immunostain (× 40): negative in the neoplastic B cells. (e) Ki-67 immunostain (× 40): elevated proliferative index in the large cell infiltrate. BCL2: B-cell lymphoma 2; BCL6: B-cell lymphoma 6; MUM-1: multiple myeloma oncogene 1. |

The PET scan revealed F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid lymphadenopathy with central necrosis in bilateral cervical lymph nodes as well as hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy in the left IIa and IIb lymph node stations. Importantly, focal wall thickening at the base of the cecum and the proximal portion of the ascending colon was identified, which demonstrated hypermetabolic activity suggestive of possible colonic involvement. A bone marrow biopsy was done which did not show any evidence of involvement with lymphoma. Considering the above findings, the patient commenced combination chemotherapy with R-CHOP.

Subsequent confirmation of cecum as an extra-nodal site of lymphoma

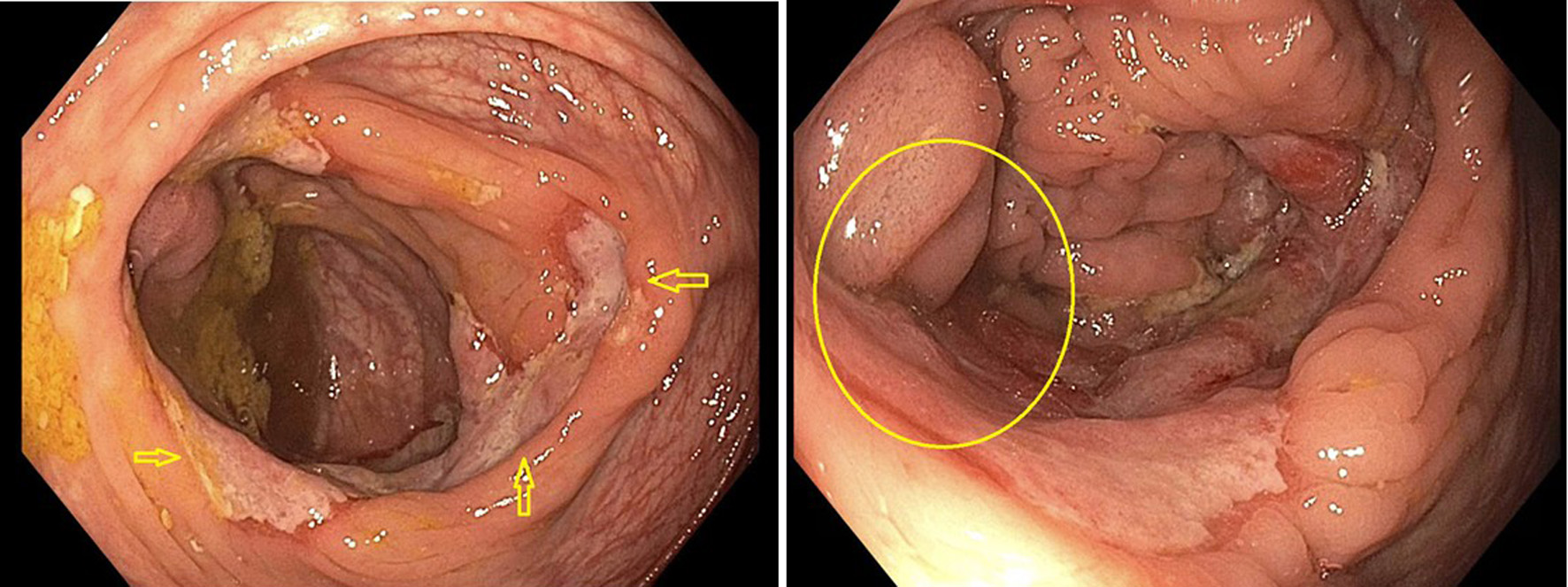

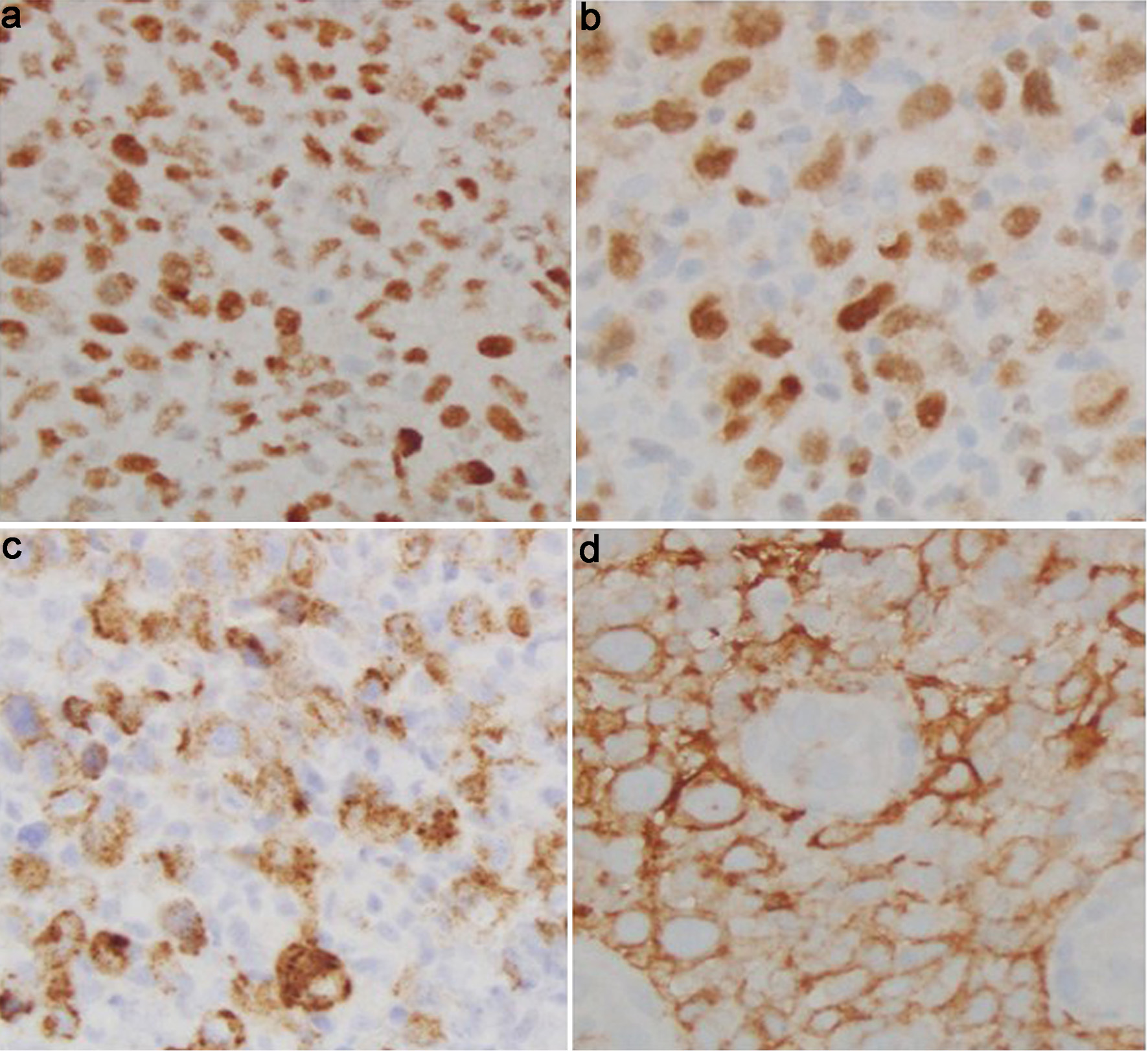

Gastroenterology consultation was requested for evaluation of the colonic abnormalities noted on the PET scan. A colonoscopy was performed, which revealed a solitary 15 mm ulcer in the cecum that was biopsied with cold forceps for histology (Fig. 4). Biopsy of the ulcerated colonic mucosa demonstrated infiltration by sheets of large atypical lymphoid cells (Fig. 5a, b). Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed B-cell lineage, with the neoplastic cells showing positive staining for PAX5 and CD79a (Fig. 5c, d). CD20 was negative, consistent with prior anti-CD20 (rituximab) therapy (Fig. 6a). Ki-67 immunostaining revealed a markedly elevated proliferative index within the large cell infiltrate (Fig. 6b). Immunostaining for CD3 was negative (Fig. 6c). The neoplastic cells were also positive for Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (EBV-LMP1), CD10, BCL6, and MUM1 (Fig. 7a-d). Additionally, co-expression of C-MYC and BCL2 was demonstrated, indicating a “double-expressor” phenotype, which is typically associated with a more aggressive clinical course (Fig. 6d, e). Based on these findings, and according to the Hans algorithm, the lesion was classified as DLBCL, germinal center B-cell (GCB) subtype.

Click for large image | Figure 4. Solitary 15 mm ulcer in cecum on colonoscopy. Arrows indicate the extent and dimensions of ulcer. Circle indicates distortion of ileocecal valve from the ulcer. |

Click for large image | Figure 5. Cecal tumor histology. (a) H&E (× 40): cecal mucosa involved by a large atypical lymphoid infiltrate. No Hodgkin/HRS-like morphology seen. (b) H&E (× 10): cecal mucosa involved by a large atypical lymphoid infiltrate. (c) PAX5 immunostain (× 40): positive in the abnormal infiltrate, confirming B-cell lineage. (d) CD79a immunostain (× 40): positive in the abnormal infiltrate confirming B-cell lineage. H&E: hematoxylin and eosin. |

Click for large image | Figure 6. Cecal tumor histology. (a) CD20 immunostain (× 40): negative in the B-cell infiltrate, consistent with anti-CD20 therapy. (b) Ki-67 immunostain (× 40): elevated proliferative index in the large cell infiltrate. (c) CD3 immunostain (× 40): negative in the neoplastic B cells. Admixed CD3+ small T cells. (d) BCL2 immunostain (× 40): positive in the neoplastic B cells. (e) C-MYC immunostain (× 20): positive (> 35%) in the neoplastic B cells. BCL2: B-cell lymphoma 2. |

Click for large image | Figure 7. Cecal tumor histology. (a) BCL6 immunostain (× 40): positive in the neoplastic B cells. (b) MUM1 immunostain (× 40): positive in the neoplastic B cells. (c) EBV-LMP1 immunostain (× 40): positive in the neoplastic B cells. (d) CD10 immunostain (× 40): positive in the neoplastic B cells. BCL6: B-cell lymphoma 6; EBV-LMP1: Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1; MUM-1: multiple myeloma oncogene 1. |

Treatment and response

Six cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy were given over a period of 3 months. His clinical course was complicated by the development of deep venous thrombosis, requiring initiation of rivaroxaban.

A repeat PET scan was done to determine the response to chemotherapy. The PET scan showed a complete response of the lymphadenopathy in the head and neck region, with persistent significant uptake in the cecal mass (standardized uptake value 23.2, previously 27.3). Since the cecal lymphoma did not respond appropriately to chemotherapy, second line treatment options, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T therapy) and autologous stem cell transplant, were considered. The patient declined CAR-T therapy due to its potential neurological side effects.

The patient sought a second opinion from a different oncologist and was given the option of repeating the PET-CT scan with surveillance if his disease remained stable. The patient opted for surveillance. Therefore, a repeat PET-CT was performed, which showed metabolically active diffuse cecal wall thickening with slightly increased activity. Necrotic conglomerate lymphadenopathy in the right neck exhibited decreased FDG activity. Interval development of right hydroureteronephrosis was noted.

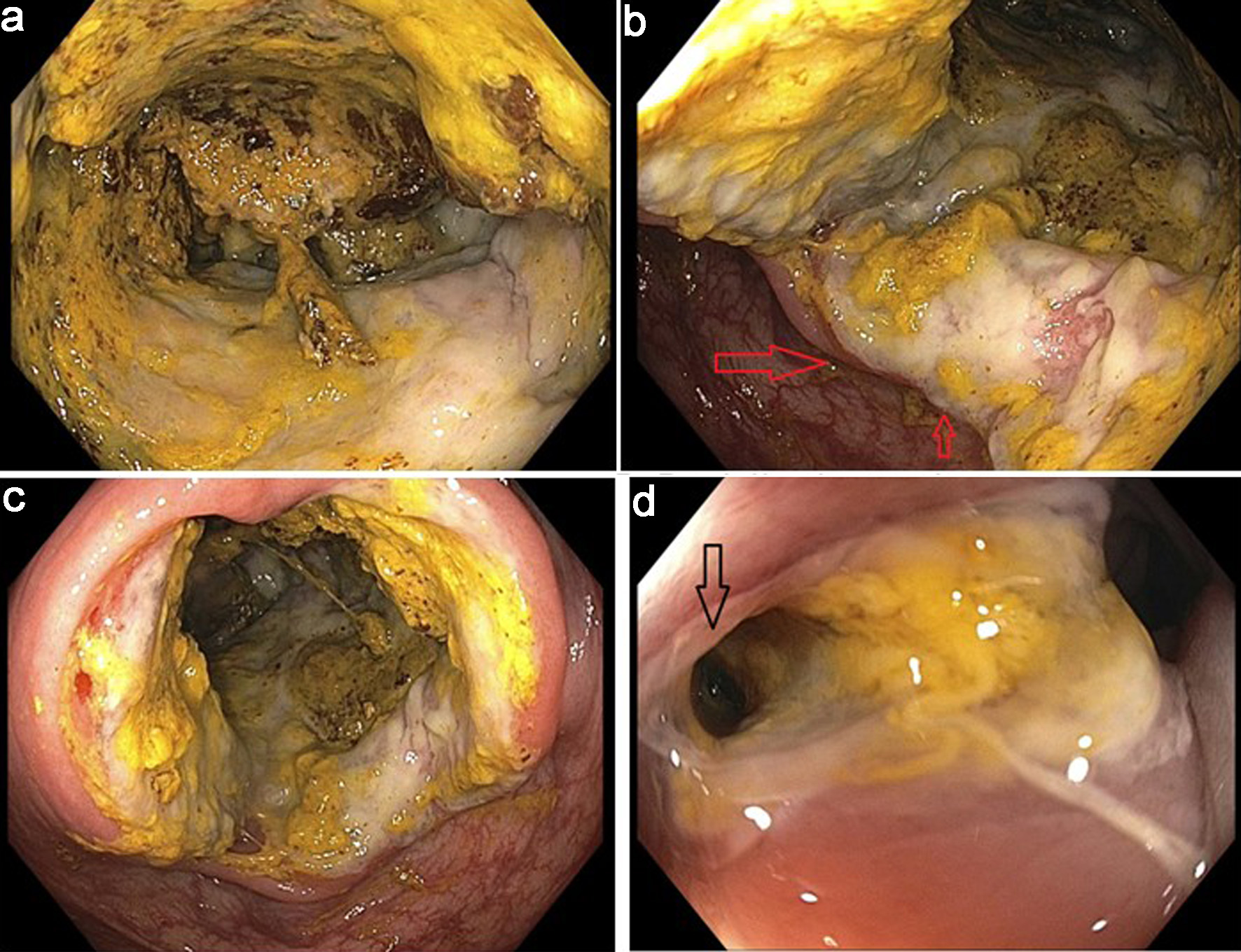

Due to the persistent abnormality noted on the PET scan, a repeat colonoscopy was performed. An infiltrative and ulcerated obstructing large mass was found in the cecum, measuring 14 mm, which was biopsied (Fig. 8a-c). There was an appearance of an ulcerated fistula in the rectum; biopsies were obtained (Fig. 8d). Both the cecal mass and rectal biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of recurrent DLBCL.

Click for large image | Figure 8. Infiltrative and ulcerated obstructing large cecal mass and rectal fistula. (a) Infiltrative cecal mass. (b) Partially obstructive cecal mass (arrows). (c) Ulcerated cecal mass. (d) Ulcerated fistula in rectum (arrow). |

Complications

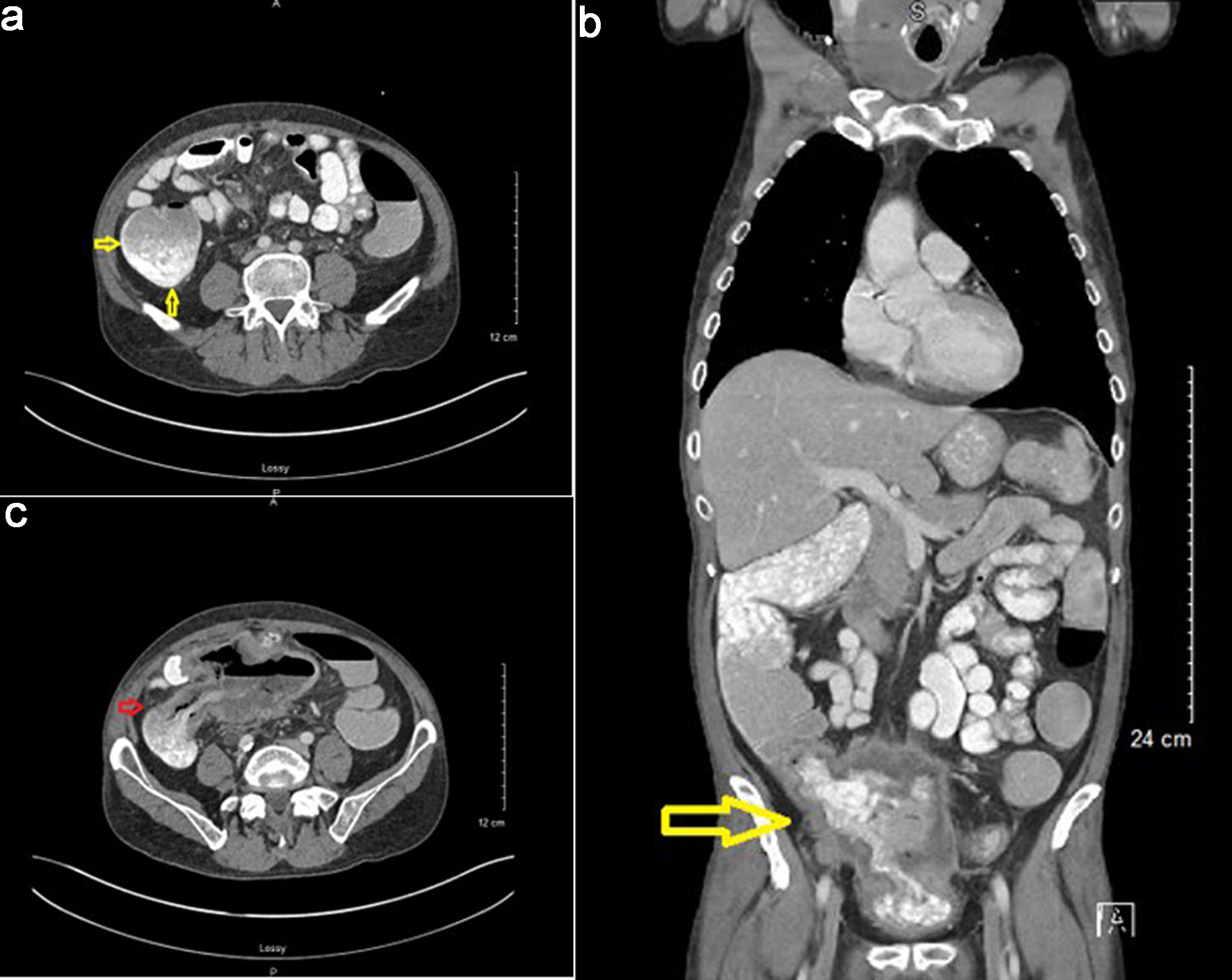

The patient was then hospitalized for severe diarrhea due to Clostridium difficile colitis and was treated with vancomycin. During this hospitalization, a CT scan of the abdomen with an oral and intravenous contrast was obtained. This revealed a markedly distended cecum with thick-walled changes (Fig. 9a), significant inflammatory stranding, and overt fistulization to the bladder. Dense oral contrast material was noted within the bladder (Fig. 9b, c). Unfortunately, due to the mass effect and colovesical fistula, the patient developed obstructive uropathy, necessitating the placement of a right-sided nephrostomy tube. He developed a urinary tract infection with E. coli as well, which was treated with antibiotics.

Click for large image | Figure 9. Computed tomography (CT) scan with oral and IV contrast findings. (a) Markedly distended cecum with thick-walled changes (arrows). (b) Oral contrast noted in bladder indicating a presence of a colovesical fistula (arrow). (c) Dense oral contrast material traversing colovesical fistula (arrow). |

The patient was then re-hospitalized due to worsening renal function. Due to progression of lymphoma with cecal involvement eroding into adjacent structures and associated urological complications, and given prior failure of R-CHOP therapy, the patient was started on salvage chemotherapy with rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (R-ICE). He received two cycles of R-ICE. A diverting loop ileostomy was performed.

Unfortunately, the patient did not respond to R-ICE chemotherapy. Given the lack of response to prior chemotherapy regimens, the decision was made to initiate treatment with rituximab and polatuzumab on a 6-week cycle, administered every 21 days.

Radiation therapy was not recommended due to concerns about exacerbating the colovesical fistula and the proximity of the mass to the bowel.

Final outcome

Despite these interventions, the patient’s disease continued to progress. Unfortunately, he passed away due to complications related to his underlying lymphoma. An autopsy was not performed.

This case highlights the importance of thorough evaluation for extranodal involvement in patients with NHL, especially when atypical symptoms or imaging findings are present. In this case, lymphoma involving the colon was refractory to chemotherapy and resulted in complications culminating in fatality.

Table 1 shows the brief summary of the clinical course.

Click to view | Table 1. Timeline of Clinical Course |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

We report a rare case of a 56-year-old male with cecal involvement of DLBCL who initially presented with a neck mass, B-symptoms, and weight loss. Histopathology confirmed a GCB subtype DLBCL with a high Ki-67 proliferation index (80-90%) and a double-expressor phenotype (MYC/BCL2 co-expression). Despite frontline R-CHOP chemotherapy and subsequent salvage R-ICE regimen, the patient exhibited primary refractory disease and ultimately developed a colovesical fistula, complicated by recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) and renal failure. Radiotherapy was withheld due to the presence of the fistula, given the risk of worsening fistulation. This constellation of features, cecal involvement, double-expressor status, primary chemotherapy refractoriness, and fistula formation, makes this case clinically unique and highlights several important diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

DLBCL is the most common type of NHL, accounting for approximately 40% of all cases. R-CHOP remains the standard first-line therapy and cures about 60% of patients, while roughly 40% are either refractory or relapse [9]. Chemo refractoriness, as observed in our patient, represents a high-risk clinical scenario.

Double-expressor lymphoma (DEL) is known for aggressive clinical characteristics, including high Ki-67 proliferation indices, elevated International Prognostic Index (IPI) scores, involvement of multiple extranodal sites, and a higher prevalence of non-germinal center B-cell (non-GCB) subtypes. Our patient exhibited several of these high-risk features, including GCB phenotype, markedly elevated Ki-67 (80-90%), and cecal involvement, which aligns with the aggressive disease patterns as reported by Riedell and Smith (2018) [10] and Green et al (2012) [11].

DEL has been consistently associated with poor outcomes when treated with standard R-CHOP therapy. Green et al (2012) [11] and Hu et al (2013) [12] reported 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) of only 27-32% and overall survival (OS) of 30-36% in DEL patients. In our case, the disease remained refractory to both R-CHOP and salvage R-ICE regimens, which aligns with these prior findings. Furthermore, Zhang et al (2019) [13] demonstrated that intensive regimens such as DA-EPOCH-R do not significantly improve survival in DEL patients, which is consistent with the poor response observed in our patient. These findings highlight the challenges in managing DEL. Thus, our case underscores the high-risk nature of DEL and the limitations of conventional therapy. As Ning et al (2012) [14] suggested, novel therapeutic strategies, including histone deacetylase inhibitors and other targeted agents, may be required to improve outcomes in this high-risk population.

Recent evidence suggests that chemotherapy refractoriness in GI DLBCL may result from a complex interplay between gut microbiota dysbiosis and alterations in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Disruption of microbial diversity and enrichment of pro-inflammatory taxa can compromise mucosal integrity, promote systemic inflammation, and impair immune-mediated tumor control, collectively diminishing chemoimmunotherapy efficacy [15]. Simultaneously, immune escape mechanisms within the TME, such as downregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II molecules, and dysregulation of macrophage phagocytic signaling through TMEM30A mutations or CD47 overexpression further hinder effective antitumor responses [16]. These microenvironmental and microbial factors may synergistically contribute to the aggressive course and limited treatment response observed in primary cecal DLBCL, highlighting the need for integrated approaches that consider host-microbiome-tumor interactions in therapeutic planning.

DLBCL pathogenesis involves genetic and molecular alterations such as BCL6 overexpression, TP53 inactivation, and dysregulation of BCL2 and MYC, leading to genomic instability, immune evasion, and aggressive tumor behavior [17, 18]. Resistance to R-CHOP in DLBCL is frequently driven by genetic and molecular abnormalities. Double-hit lymphomas (DHLs), harboring concurrent MYC and BCL2 rearrangements, and triple-hit lymphomas (THLs), involving MYC, BCL2, and BCL6, are consistently associated with poor outcomes and limited response to standard therapy [19, 20]. Similarly, double protein expression lymphoma (DPL), defined by high MYC and BCL2 protein levels without detectable gene rearrangements, also predicts inferior survival, though slightly better than DHL [19, 21]. Isolated MYC or BCL2 alterations, as well as specific MYC mutations, have variable prognostic significance [22-25]. These findings underscore the need for early molecular screening using FISH for gene rearrangements and immunohistochemistry for protein overexpression, as conventional prognostic tools, including the IPI, often fail to identify patients at high risk of treatment resistance [19, 20].

Tumor-associated bowel fistulas, including enterovesical, enterocolic, and less commonly splenocolic or gastrosplenic fistulas, are rare but serious complications of primary GI lymphoma, particularly DLBCL [26-34]. These fistulas may result from transmural tumor invasion, local inflammatory changes, adherence to adjacent organs, or treatment-related cytotoxic injury, including post-chemotherapy tumor regression leading to wall weakness [28-30, 32]. Clinical manifestations are often nonspecific, ranging from abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss to acute complications such as GI bleeding or partial bowel obstruction, which may delay diagnosis [26, 27, 33, 34]. Imaging modalities including CT, CT angiography, and CT enterography are crucial for early detection, localization of fistulas, and surgical planning, while endoscopy may fail to reveal lesions in some cases [28, 29, 31, 33]. Literature reviews indicate that fistulas can rarely present as the initial manifestation of primary intestinal lymphoma, with the small intestine and colon being the most commonly involved sites, and DLBCL being the predominant histologic type [26, 27, 33]. Management often requires a multidisciplinary approach, combining surgery for resection or drainage with chemotherapy, including R-CHOP regimens, which has been associated with improved survival and functional outcomes [26-29, 30, 32, 34]. While long-term prognosis remains variable, early recognition and timely intervention are pivotal in reducing morbidity and mortality in these patients [26, 27, 33, 34].

In summary, DLBCL typically presents as an enlarging symptomatic mass, often as a growing nodule in the neck or abdomen. Patients frequently report systemic “B” symptoms, including fever, weight loss, and night sweats, which are indicative of advanced disease [35]. As in this case, the presence of “B” symptoms, advanced disease stage, and the patient’s age (greater than 58 years) are recognized as poor prognostic factors for colon lymphoma [36]. In the context of GI involvement, particularly colon lymphoma patients may present with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and GI bleeding, with bowel obstruction occurring in rare instances. The absence of extra-nodal symptoms, as in this case, highlights the importance of recognizing primary symptoms and utilizing imaging modalities such as CT scans for comprehensive evaluation of potential lymphoma sites. The diagnosis is best made by excisional tissue biopsy which allows for definitive histopathological assessment [37].

Management of GI DLBCL involves a multidisciplinary approach, with surgery reserved for large or obstructive tumors and standard chemotherapy consisting of six cycles of R-CHOP [38]. Ongoing monitoring is essential to assess remission, manage treatment related complications, and facilitate early detection of extracolonic malignancies through age-appropriate screening colonoscopies. In older patients, treatment should be individualized based on fitness rather than age: fit patients may receive standard R-CHOP, unfit patients can benefit from dose-reduced regimens such as R-Mini CHOP or anthracycline alternatives (R-CEOP/gemcitabine), while frail patients may not tolerate chemotherapy [39]. Geriatric assessments, prephase corticosteroids, primary granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) prophylaxis help optimize outcomes and minimize toxicity. These observations highlight the need for tailored treatment strategies for high-risk DLBCL and integrating molecular and genetic profiling with conventional and novel therapies may improve precision medicine approaches and patient outcomes [38, 39].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this case highlights that the GI tract involvement of DLBCL, especially metastatic spread to cecum, is a rare occurrence. Early diagnosis of extra-nodal involvement - particularly colonic lesion as seen in our case - is crucial, and clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for GI extra-nodal disease in patients presenting with atypical or nonspecific symptoms, even in the absence of clear GI manifestations. Screening colonoscopy could play a pivotal role in diagnosing these lesions ahead of time. Early recognition, especially in tumors with high-risk or chemo-refractory features, may allow for timely surgical intervention and help prevent significant local complications and morbidity. Once suspected, the excisional biopsy of incidental mass is confirmatory. However, treatment options are limited given the scarcity of data. In short, it is imperative for physicians to maintain a high level of suspicion of this clinical entity in NHL-DLBCL patients presenting without any primary GI symptoms as early diagnosis and management can lead to potentially favorable outcomes.

Learning points

Early identification and diagnosis of extranodal involvement in DLBCL through imaging modalities such as PET-CT, especially in patients without gastrointestinal symptoms, is crucial. This facilitates timely decisions regarding chemotherapy and, when necessary, early surgical intervention, thereby preventing significant morbidity and local complications.

Screening colonoscopy also plays a vital role, not only in detecting polyps and colonic adenocarcinoma but also in identifying atypical lesions, that may lead to the diagnosis of rare malignancies. In our case, age-appropriate colon cancer screening might have led to an earlier diagnosis and identification of extranodal colonic involvement, potentially preventing significant complications, enabling timely treatment, and reducing morbidity.

It is essential to recognize aggressive tumor features and remain vigilant about the potential for chemo-refractory disease.

Management of such difficult-to-treat tumors requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach involving specialists from urology, surgery, hematology-oncology, and gastroenterology.

Acknowledgments

This article was previously presented as a meeting abstract at the 2022 ACG Annual Scientific Meeting on October 21-26, 2022.

Financial Disclosure

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Author Contributions

Usama Sakhawat, primary author, contributed to all parts of the report from collecting data, writing abstract, case presentation, literature review, discussion, and finalizing/reviewing the final version. Ahmed Shehadah and Usman Mazhar contributed to literature review and discussion. Miranda Gonzalez contributed to case presentation, abstract, and conclusion. Fahad Malik and Leslie Bank contributed to discussion and conclusion. James Van Gurp contributed to case presentation, discussion, and conclusion.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Thandra KC, Barsouk A, Saginala K, Padala SA, Barsouk A, Rawla P. Epidemiology of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Med Sci (Basel). 2021;9(1):5.

doi pubmed - Bairey O, Ruchlemer R, Shpilberg O. Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas of the colon. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8(12):832-835.

pubmed - Moller MB, Pedersen NT, Christensen BE. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: clinical implications of extranodal versus nodal presentation—a population-based study of 1575 cases. Br J Haematol. 2004;124(2):151-159.

doi pubmed - Calomino N, Fusario D, Cencini E, Lazzi S. Two secondary localisation of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas in the upper gastrointestinal tract. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(5):e247607.

doi pubmed - George DM, Lakshmanan A. Lymphomas with primary gastrointestinal presentation: a retrospective study covering a five-year period at a quaternary care center in Southern India. Cureus. 2024;16(12):e75161.

doi pubmed - Kasouha G, et al. Gastrointestinal tract lymphomas: a review of the clinicopathologic features and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145(12):1585-1594.

doi - Prognostic impact of gastrointestinal involvement in newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):5400.

doi - Sehn LH, Salles G. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):842-858.

doi pubmed - Susanibar-Adaniya S, Barta SK. 2021 Update on Diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a review of current data and potential applications on risk stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(5):617-629.

doi pubmed - Riedell PA, Smith SM. Double hit and double expressors in lymphoma: definition and treatment. Cancer. 2018;124(24):4622-4632.

doi pubmed - Green TM, Young KH, Visco C, Xu-Monette ZY, Orazi A, Go RS, Nielsen O, et al. Immunohistochemical double-hit score is a strong predictor of outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(28):3460-3467.

doi pubmed - Hu S, Xu-Monette ZY, Tzankov A, Green T, Wu L, Balasubramanyam A, Liu WM, et al. MYC/BCL2 protein coexpression contributes to the inferior survival of activated B-cell subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and demonstrates high-risk gene expression signatures: a report from The International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program. Blood. 2013;121(20):4021-4031; quiz 4250.

doi pubmed - Zhang XY, Liang JH, Wang L, Zhu HY, Wu W, Cao L, Fan L, et al. DA-EPOCH-R improves the outcome over that of R-CHOP regimen for DLBCL patients below 60 years, GCB phenotype, and those with high-risk IPI, but not for double expressor lymphoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145(1):117-127.

doi pubmed - Ning ZQ, Li ZB, Newman MJ, Shan S, Wang XH, Pan DS, Zhang J, et al. Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000): a new histone deacetylase inhibitor of the benzamide class with antitumor activity and the ability to enhance immune cell-mediated tumor cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69(4):901-909.

doi pubmed - Caserta S, Alvaro ME, Penna G, Fazio M, Stagno F, Allegra A. Gut microbiota dysbiosis and dietary interventions in non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas: implications for treatment response. Biomedicines. 2025;13(9):2141.

doi pubmed - Ennishi D. The biology of the tumor microenvironment in DLBCL: Targeting the "don't eat me" signal. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2021;61(4):210-215.

doi pubmed - Choi SY, Kim SJ, Kim WS, Kim K, Ko YH. Aggressive B cell lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract: clinicopathologic and genetic analysis. Virchows Arch. 2011;459(5):495-502.

doi pubmed - Cakmak A, Yilmaz A, Yildiz M. Prognostic significance of P53, Bcl-2, and Fas expression in patients with primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Erciyes Med J. 2015;37(2):67-73.

doi - Sarkozy C, Traverse-Glehen A, Coiffier B. Double-hit and double-protein-expression lymphomas: aggressive and refractory lymphomas. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(15):e555-e567.

doi pubmed - Xu-Monette ZY, Dabaja BS, Wang X, Tu M, Manyam GC, Tzankov A, Xia Y, et al. Clinical features, tumor biology, and prognosis associated with MYC rearrangement and Myc overexpression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with rituximab-CHOP. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(12):1555-1573.

doi pubmed - Johnson NA, Slack GW, Savage KJ, Connors JM, Ben-Neriah S, Rogic S, Scott DW, et al. Concurrent expression of MYC and BCL2 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(28):3452-3459.

doi pubmed - Caponetti GC, Dave BJ, Perry AM, Smith LM, Jain S, Meyer PN, Bast M, et al. Isolated MYC cytogenetic abnormalities in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma do not predict an adverse clinical outcome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(11):3082-3089.

doi pubmed - Copie-Bergman C, Cuilliere-Dartigues P, Baia M, Briere J, Delarue R, Canioni D, Salles G, et al. MYC-IG rearrangements are negative predictors of survival in DLBCL patients treated with immunochemotherapy: a GELA/LYSA study. Blood. 2015;126(22):2466-2474.

doi pubmed - Xu-Monette ZY, Deng Q, Manyam GC, Tzankov A, Li L, Xia Y, Wang XX, et al. Clinical and biologic significance of MYC genetic mutations in de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(14):3593-3605.

doi pubmed - Iqbal J, Meyer PN, Smith LM, Johnson NA, Vose JM, Greiner TC, Connors JM, et al. BCL2 predicts survival in germinal center B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with CHOP-like therapy and rituximab. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(24):7785-7795.

doi pubmed - Kumar A, West JC, Still CD, Komar MJ, Babameto GP. Jejunocolic fistula: an unreported complication of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated lymphoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34(2):194-195.

doi pubmed - Wang V, Dorfman DM, Grover S, Carr-Locke DL. Enterocolic fistula associated with an intestinal lymphoma. MedGenMed. 2007;9(1):28.

pubmed - Golabek T, Szymanska A, Szopinski T, Bukowczan J, Furmanek M, Powroznik J, Chlosta P. Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:617967.

doi pubmed - Ansari MS, Nabi G, Singh I, Hemal AK, Pandey G. Colovesical fistula an unusual complication of cytotoxic therapy in a case of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Int Urol Nephrol. 2001;33(2):373-374.

doi pubmed - Altfillisch C, Reddy P, Srinivasan S, Jackson M. A rare gastrosplenic fistula treated endoscopically in a post-chemotherapy patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S):e2331.

doi - Gajjar BA, Gabriel J, Minhas A, Schmidt L. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as partial small bowel obstruction and a fistula. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(Suppl):S1454.

doi - Luca T, Sergi M, Coco O, Leone E, Chisari G, Fontana P, Castorina S. Splenocolic fistula in a patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a case report and review of literature. Front Surg. 2022;9:979463.

doi pubmed - Zhao RJ, Zhang CL, Zhang Y, Sun XY, Ni YH, Luo YP, Li J, et al. Enteral fistula as initial manifestation of primary intestinal lymphoma. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133(1):101-102.

doi pubmed - Chiang SW, Chiang TW. Colo-enteric fistula associated with diffuse large B cell lymphoma that resulted in gastrointestinal bleeding: a case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;91:106798.

doi pubmed - Hui D, Proctor B, Donaldson J, Shenkier T, Hoskins P, Klasa R, Savage K, et al. Prognostic implications of extranodal involvement in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(9):1658-1667.

doi pubmed - d'Amore F, Brincker H, Gronbaek K, Thorling K, Pedersen M, Jensen MK, Andersen E, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a population-based analysis of incidence, geographic distribution, clinicopathologic presentation features, and prognosis. Danish Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(8):1673-1684.

doi pubmed - Vetro C, Romano A, Amico I, Conticello C, Motta G, Figuera A, Chiarenza A, et al. Endoscopic features of gastro-intestinal lymphomas: from diagnosis to follow-up. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(36):12993-13005.

doi pubmed - Sehn LH, Congiu AG, Culligan DJ, et al. No added benefit of eight versus six cycles of CHOP when combined with rituximab in previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients: Results from the international phase III GOYA study. Blood. 2018;132(6):783-793.

doi - Lugtenburg PJ, Mutsaers P. How I treat older patients with DLBCL in the frontline setting. Blood. 2023;141(21):2566-2575.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.