| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 10, October 2025, pages 406-409

Vasovagal Syncope in Penoscrotal Inflatable Penile Prosthesis Implantation Following Spinal Anesthesia

Department of Urology, College of Medicine, Majmaah University, Al-Majmaah 11952, Saudi Arabia

Manuscript submitted August 11, 2025, accepted September 30, 2025, published online October 19, 2025

Short title: Vasovagal Reactions During PPI

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5189

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Spinal anesthesia (SA) is increasingly recognized as a preferred alternative to general anesthesia (GA). Nonetheless, several factors must be carefully considered to ensure safe and practical application. Vasovagal syncope (VVS) or vasovagal reaction, characterized by a sudden decrease in heart rate (HR) and/or blood pressure (BP), is common during pain management procedures and SA administration in patients undergoing surgery. We report the case of a 57-year-old male who underwent SA during penoscrotal inflatable penile prosthesis (IPP) implantation. During the corporotomy closure, the patient developed a brief episode of sudden severe bradycardia and low BP, which was attributed to VVS. Penile prosthesis implantation (PPI) is commonly performed with SA. Both urologists and anesthesiologists strongly recommend identifying important risk factors, such as VVS, before SA to facilitate monitoring and rapid response to VVS during the procedure.

Keywords: Penile prosthesis; Syncope; Vasovagal; Anesthesia; Erectile dysfunction

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The advantages of spinal anesthesia (SA) are beginning to be widely recognized as viable alternatives to general anesthesia (GA) [1]. Opting for SA in the lower abdominal, lower limb, pelvic, and perineal surgeries and specific urological procedures may offer advantages over GA [2, 3]. Patients who received penile prosthesis implantation (PPIs) under SA require fewer intravenous (IV) pain medications and treatment for nausea and vomiting. SA may provide improved analgesia during the short procedure while sparing the systemic effects of GA [4].

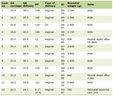

Table 1 [5-7] provides an overview of the pathophysiological features, clinical classification, symptomatology, and potential complications associated with vasovagal syncope (VVS).

Click to view | Table 1. The Definition, Types, Clinical Features, and Potential Complications of Vasovagal Syncope (VVS) |

It is essential for andrologists to recognize intraoperative VVS for early identification and immediate initiation of effective treatment. Failure to intervene promptly can result in rapid progression and high mortality, highlighting the need for effective management strategies.

This report presents a case of a patient who underwent elective inflatable penile prosthesis (IPP) for refractory erectile dysfunction (ED) and developed VVS during penoscrotal IPP implantation.

This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE checklist [8].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 57-year-old married, retired male with a past medical history of diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia managed with oral medications presented to the andrology clinic with complaints of weak erection and failure of different dosages and types of oral ED medications. He had no known allergies and was a non-smoker. Counseling was provided as an alternative treatment option, and the patient chose a three-piece IPP. Informed consent was obtained, and preoperative assessment, blood and urine test, chest X-ray, and electrocardiogram (ECG) were all within normal limits. Following the clearance of anesthesia, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score was class II. The patient was admitted for an elective PPI. Upon admission, the patient’s vitals were stable, and he received standard perioperative antibiotic treatment with vancomycin and gentamycin. The patient underwent SA with dexmedetomidine (DEX) and was monitored routinely using ECG, noninvasive arterial pressure, and oxygen saturation. Initial vital signs included a heart rate (HR) of 89 beats per minute (bpm), normal sinus rhythm, and a blood pressure (BP) of 124/56 mm Hg.

After shaving the genitalia area, the surgical fields were prepared with a customary 10-min scrub wash, followed by aseptic prepping and draping. Antimicrobial incise drapes were applied and a closed urethral catheter drainage system was inserted. The procedure was performed using a standard technique with vertical penoscrotal incision. The insertion of the Titan® OTR IPP, including reservoir and cylinders, was accomplished. However, approximately 3 - 5 min after the corporotomy closure began, a sudden decrease in HR to 26 bpm and BP to 94/56 mm Hg was observed on the intraoperative monitor. In response, the anesthesia team requested that the surgical team cease tissue handling and traction. Massive bleeding or hypotension were not observed. IV atropine (1 mg) was promptly administered. Following atropine administration, the patient’s vital signs were stabilized, with an HR of 95 bpm and a BP of 138/74 mm Hg within approximately 60 s. Notably, there were no indications of arrhythmia or reflex bradycardia, and the intraoperative ECG showed the sinus rhythm. When the patient’s condition was stabilized, the procedure was resumed, with complete closure of the corporotomy and placement of a pump at the gravity-dependent location. The wound was closed. The penile implant remained semi-inflated, and the urethral catheter was securely fixed. The wound was dressed, and a mummy wrap was applied. Subsequently, he was transferred to the recovery room. The postoperative recovery proceeded seamlessly. The cardiology team performed serial troponin and ECG assessments during recovery and in the ward, yielding results within the normal range. Upon evaluation, the patient mentioned that he had a history of vasovagal episodes or vasovagal syncope (VVS) thrice in his life, which occurred during stressful situations, such as during blood sampling. The cardiological assessment revealed that the occurrence was likely a vagal response to SA. During follow-up, the patient recovered smoothly with no active issues. Prosthesis activation was at 3 - 4 weeks postoperatively, and the patient could resume sexual intercourse after 6 weeks.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This is the first reported case of a patient who underwent penoscrotal inflatable PPI and developed VVS following SA. This case is valuable for andrologists and penile prosthesis implanters as it highlights the need to recognize the risk factors, implement preventive measures, and effectively manage VVS in operating room settings.

Previous literature has reported VVS due to intervention or procedures in male genitourinary, such as VVS due to bladder overdistension or during cystoscopy [9, 10]. Similar vasovagal responses have been observed during other urological procedures such as cystoscopy and testicular manipulation [11-13]. Our report is the first to address VVS during PPI treatment.

Several factors are associated with the occurrence of VVS after interventional pain management (IPM). The most significant risk factor is a history of VVS because individuals with a previous occurrence are predisposed to future reactions [14, 15]. Additional factors contributing to VVS include male gender, age above 65 years, and higher pre-procedural pain scores. A study by Kennedy et al in 2013 [16] indicated that men were twice as likely as women to experience VVS during IPM procedures. While the reasons remain unclear, studies suggest that increased muscle mass may have led to a more significant drop in blood pressure. Additional factors indicated as potential risk factors for VVS include baseline hypotension, bradycardia, dehydration, and anxiety [14, 17]. Notably, the patient disclosed only postoperatively that he had experienced three prior VVS episodes, including during blood drawing. This omission highlights a critical failure in preoperative risk stratification. Potential VVS occurrences can be reduced by identifying the factors that lead to VVS incidents during anesthetic administration, improving patient education regarding the use of spinal or regional anesthesia, and reducing anxiety by preoperative anxiolytic treatment [17]. The most frequently encountered immediate adverse event in IPM procedures is the VVS, with rates varying from 0% to 4% in the literature [5]. Bradycardia occurs in approximately 13% of the patients [18]. In the context of sympathectomy induced by either general or neuraxial anesthesia, abrupt activation of the vagus nerve and/or a sudden decrease in sympathetic tone can lead to severe vasovagal responses [19]. Due to the administration of DEX in SA, bradycardia occurs in approximately 13-30% of patients, varying based on the loading dose of DEX used [20, 21]. In our case, concomitant DEX sedation during SA may have amplified vagal excitability and contributed to the profound bradycardic episode.

The mechanisms underlying VVS during IPM procedures are complex and not fully understood. In the context of epidural steroid injections, some theories propose that epidural anesthesia may cause sympathetic blockade, leading to decreased venous tone and reduced cardiac output [5].

Continuous monitoring of vital signs is essential for most patients undergoing IPM. These included pulse oximetry, ECG, and BP assessments before and during the procedure. Such monitoring is vital in individuals with a history of VVS to similar procedures. In the event of bradycardia and/or vasodepression, immediate cessation of the procedure is imperative [14]. The patient should be given a cold compress, such as an ice pack, to apply to the neck. Additionally, the patient should be positioned either lying flat on their back (supine) or in the Trendelenburg position, where the table is tilted so that the patient’s head is lower than their feet at an angle of approximately 15° to 30° [14].

Patients can be encouraged to perform counterpressure techniques, such as crouching or crossing the leg, which may enhance the rate of blood flow back to the heart and cardiac output. If conservative management is ineffective, IV fluids should be started (if these have not already been administered before surgery). Additionally, vasoactive medications, such as ephedrine in increments of 5 - 10 mg, glycopyrrolate in increments of 0.2 mg, or atropine in increments of 0.4 - 1.0 mg, should be considered. If the patient’s systolic BP remains below 90 mm Hg, mean arterial pressure below 65 mm Hg, and/or HR below 50 bpm, prompt emergency intervention is warranted [14].

Conclusions

This case underscores the need for preoperative screening for vasovagal history in penile prosthesis candidates. In patients with prior syncopal events, prophylactic anticholinergics and heightened intraoperative vigilance may help prevent catastrophic bradycardic episodes under SA.

Learning points

This study highlights several important aspects of the clinical presentation and diagnosis of VVS during PPI surgeries. It emphasizes a clinically relevant issue for both urologists and anesthesiologists. The novelty lies in drawing attention to intraoperative VVS risk stratification, monitoring, and prompt management in prosthetic urology.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Majmaah University for supporting this work.

Financial Disclosure

No funding was received for this work.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable

Author Contributions

Meshari A. Alzahrani drafted the manuscript and case section, conducted the literature review, performed review and editing, and created the conceptual visualization.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

SA: spinal anesthesia; GA: general anesthesia; VVS: vasovagal syncope; PPI: penile prosthesis implant; IPP: inflatable penile implant; BP: blood pressure; HR: heart rate; ECG: electrocardiography; IPM: interventional pain management

| References | ▴Top |

- Keenan C, Wang AY, Balonov K, Kryzanski J. Postoperative vasovagal cardiac arrest after spinal anesthesia for lumbar spine surgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2022;13:42.

doi pubmed - Mung'ayi V, Mbaya K, Sharif T, Kamya D. A randomized controlled trial comparing haemodynamic stability in elderly patients undergoing spinal anaesthesia at L5, S1 versus spinal anaesthesia at L3, 4 at a tertiary African hospital. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(2):466-479.

doi pubmed - Kame BS, Kumar VU, Subramaniam A. Spinal anaesthesia for urological surgery: a comparison of isobaric solutions of levobupivacaine and ropivacaine with dexmedetomidine. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2023;33(1):65-72.

doi pubmed - Henry GD, Sacca A, Eisenhart E, Cleves MA, Kramer AC. Subarachnoid versus General Anesthesia in Penile Prosthetic Implantation: Outcomes Analyses. Adv Urol. 2012;2012:696752.

doi pubmed - Malave B, Vrooman B. Vasovagal reactions during interventional pain management procedures-a review of pathophysiology, incidence, risk factors, prevention, and management. Med Sci (Basel). 2022;10(3):39.

doi pubmed - Sun L, Dong JZ, Du X, Bai R, Li S, Salim M, Ma CS. Prophylactic atropine administration prevents vasovagal response induced by cryoballoon ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;40(5):551-558.

doi pubmed - Kennedy DJ, Schneider B, Smuck M, Plastaras CT. The use of moderate sedation for the secondary prevention of adverse vasovagal reactions. Pain Med. 2015;16(4):673-679.

doi pubmed - Kerwan Ahmed, et al. Revised Surgical Case Report (SCARE) guideline: an update for the age of artificial intelligence. Premier J Sci. 2025;2025:10.100079.

- Yamaguchi Y, Tsuchiya M, Akiba T, Yasuda M, Kiryu Y, Hagiwara T, Fujishiro Y, et al. Nervous influences upon the heart due to overdistension of the urinary bladder: the relation of its mechanism to Vago-Vagal reflex. Keio J Med. 1964;13:87-99.

doi pubmed - Dykstra DD, Sidi AA, Anderson LC. The effect of nifedipine on cystoscopy-induced autonomic hyperreflexia in patients with high spinal cord injuries. J Urol. 1987;138(5):1155-1157.

doi pubmed - Alzahrani MA, Alasmari MM, Altokhais MI, Alkeraithe FW, Alghamdi TA, Aldaham AS, Hakami AH, et al. Is there a relationship between waking up from sleep and the onset of testicular torsion? Res Rep Urol. 2023;15:91-98.

doi pubmed - Okonkwo KC, Wong KG, Cho CT, Gilmer L. Testicular trauma resulting in shock and systemic inflammatory response syndrome: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1(1):4.

doi pubmed - Gorgy A, Meniru GI, Naumann N, Beski S, Bates S, Craft IL. The efficacy of local anaesthesia for percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration and testicular sperm aspiration. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(3):646-650.

doi pubmed - Vidri R, Emerick T, Alter B, Brancolini S. Managing vasovagal reactions in the outpatient pain clinic setting: a review for pain medicine physicians not trained in anesthesiology. Pain Med. 2022;23(6):1189-1193.

doi pubmed - Thijsen A, Masser B. Vasovagal reactions in blood donors: risks, prevention and management. Transfus Med. 2019;29(Suppl 1):13-22.

doi pubmed - Kennedy DJ, Schneider B, Casey E, Rittenberg J, Conrad B, Smuck M, Plastaras CT. Vasovagal rates in flouroscopically guided interventional procedures: a study of over 8,000 injections. Pain Med. 2013;14(12):1854-1859.

doi pubmed - Ekinci M, Golboyu BE, Dulgeroglu O, Aksun M, Baysal PK, Celik EC, Yeksan AN. [The relationship between preoperative anxiety levels and vasovagal incidents during the administration of spinal anesthesia]. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2017;67(4):388-394.

doi pubmed - Carpenter RL, Caplan RA, Brown DL, Stephenson C, Wu R. Incidence and risk factors for side effects of spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1992;76(6):906-916.

doi pubmed - Jang YE, Do SH, Song IA. Vasovagal cardiac arrest during spinal anesthesia for Cesarean section -A case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;64(1):77-81.

doi pubmed - Elcicek K, Tekin M, Kati I. The effects of intravenous dexmedetomidine on spinal hyperbaric ropivacaine anesthesia. J Anesth. 2010;24(4):544-548.

doi pubmed - Ahn EJ, Park JH, Kim HJ, Kim KW, Choi HR, Bang SR. Anticholinergic premedication to prevent bradycardia in combined spinal anesthesia and dexmedetomidine sedation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:13-19.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.