| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 12, December 2025, pages 493-498

Multi-Modality Imaging for Accurate Valvular Lesion Diagnosis: A Case Report of Catastrophic Outcomes From Unrecognized Severe Aortic Regurgitation

Philip Nolana, b, c, e, Bridog Nic Aodhabhuia, b, Rory O’Hanlond, Briain MacNeilla, b

aCardiology Department, University Hospital Galway and SAOLTA University Health Care Group, Galway, Ireland

bSchool of Medicine, University of Galway, Galway, Ireland

cCardiology Department, Cork University Hospital, Cork, Ireland

dCardiology Department, Blackrock Clinic, Dublin, Ireland

eCorresponding Author: Philip Nolan, Cardiology Department, Cork University Hospital, Cork, Ireland

Manuscript submitted July 25, 2025, accepted October 7, 2025, published online November 22, 2025

Short title: Multi-Imaging for Severe AR

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5177

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Aortic regurgitation (AR) can be difficult to accurately quantify on echocardiography alone, potentially leading to erroneous grading. A 52-year-old male presented following resuscitation after an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. He had been followed in the cardiology outpatient clinic for a number of years for monitoring of bicuspid aortic valve and associated AR. Regular transthoracic echocardiography and one transesophageal echocardiogram had shown moderate range AR. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging reported the AR as severe with associated severely dilated left ventricle. Echocardiography grading and the patient’s lack of symptoms supported a strategy of active surveillance. The presentation with cardiac arrest prompted re-evaluation of the severity of this patient’s AR. Repeat cardiac magnetic resonance imaging re-affirmed severe AR, and the patient proceeded to surgical aortic valve replacement with a bioprosthetic valve. Post-operatively, the patient had heart failure with severely reduced ejection fraction. During hospital stay, he developed thyrotoxicosis secondary to amiodarone. This case demonstrates the discrepancy in assessing severity between different imaging techniques and highlights the potential complications in delayed intervention in AR.

Keywords: Aortic regurgitation; Cardiac MRI; Cardiac arrest; Aortic valve replacement

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Aortic regurgitation (AR) has well-defined parameters for determining severity based on echocardiography. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) [1] and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) [2] advise use of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) when echocardiographic measurements are equivocal or discordant with clinical findings. CMRI is useful in assessing aortic dilatation, though cardiac computed tomography is advised for assessing aortic dimensions for clinical decision making.

Decisions on intervention are based on integrating imaging parameters with symptomatology and risk of progression to heart failure. Surgery for severe AR is an ACC/AHA class I recommendation in symptomatic patients, or asymptomatic patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 55% due to AR, or if undergoing another cardiac surgery. Surgery is a class IIa recommendation for asymptomatic patients with left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD) > 50 mm or LVESD > 25 mm/m2 adjusted to body surface area (BSA). Surgery is a class IIb recommendation for asymptomatic patients with progressive decrease in LVEF or increase in left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) > 50 mm or > 25 mm/m2 BSA. ESC guidelines have similar criteria.

Within guidelines is a recognition that echocardiography may be suboptimal in assessing AR in some cases. Of course, guidelines cannot cover every potential clinical scenario and many cases are not easily categorized. Additionally, patients with an indication for valve intervention may elect to postpone surgery if asymptomatic. This case is an example of AR which would have led to earlier indication for aortic valve replacement based on CMRI but was deemed moderate by echocardiographic parameters.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 52-year-old male had outpatient follow-up since 2018 for Sievers-1.1 bicuspid aortic valve and AR. Yearly echocardiography had consistently shown moderate AR, though with a markedly eccentric jet which limited quantitative measurement. He had normal LVEF and no left ventricle (LV) dilatation on echocardiography, up to July 2021. He was asymptomatic and physically active, regularly cycling long distances. Medical history included hypertension and atrial fibrillation with pulmonary vein isolation. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed left-bundle branch block (LBBB). His regular medications were apixaban, bisoprolol, and ramipril. He did not smoke nor use illicit drugs.

Coronary angiogram, done following non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) during otherwise normal an exercise stress test, showed no obstructive coronary artery disease. CMRI in February 2022, assessing for causes of NSVT, showed a severely dilated LV, mild eccentric LV hypertrophy, and LVEF of 60%. Fusion of the left and right coronary cusps was seen with resulting severe AR due to coaptation failure, though regurgitant fraction was 40%, consistent with moderate AR. Post-contrast imaging showed no late-gadolinium enhancement. Interval transthoracic echocardiogram again showed normal LVEF and dimensions with moderate LVEF. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) in July 2022 estimated moderate AR, though with some incongruous measurements - AR jet covering 40% of left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT), vena contracta 6 mm, and pressure half-time of 660 ms. The patient remained asymptomatic and continued regular long-distance cycling. After Heart Team discussion, given the patient’s lack of symptoms and the impression of moderate AR on echocardiography, ongoing active surveillance was agreed via shared decision-making, with a plan to proceed to surgery if any symptoms developed.

In January 2023, the patient collapsed without preceding symptoms. His family commenced cardiopulmonary resuscitation, which was continued by paramedics. ECG monitoring showed ventricular fibrillation. Following 14 min, including four rounds of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), four defibrillating shocks, and two doses of intravenous adrenaline, return of spontaneous circulation was achieved. After hospital transfer, the patient was electrically cardioverted for new-onset atrial fibrillation and started on intravenous amiodarone. He was intubated and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). ECG showed LBBB pattern. Electrolytes were normal. In the preceding month, the patient had been treated with doxycycline and co-amoxiclav for mild but persistent community-diagnosed respiratory infection, but had maintained his baseline active lifestyle.

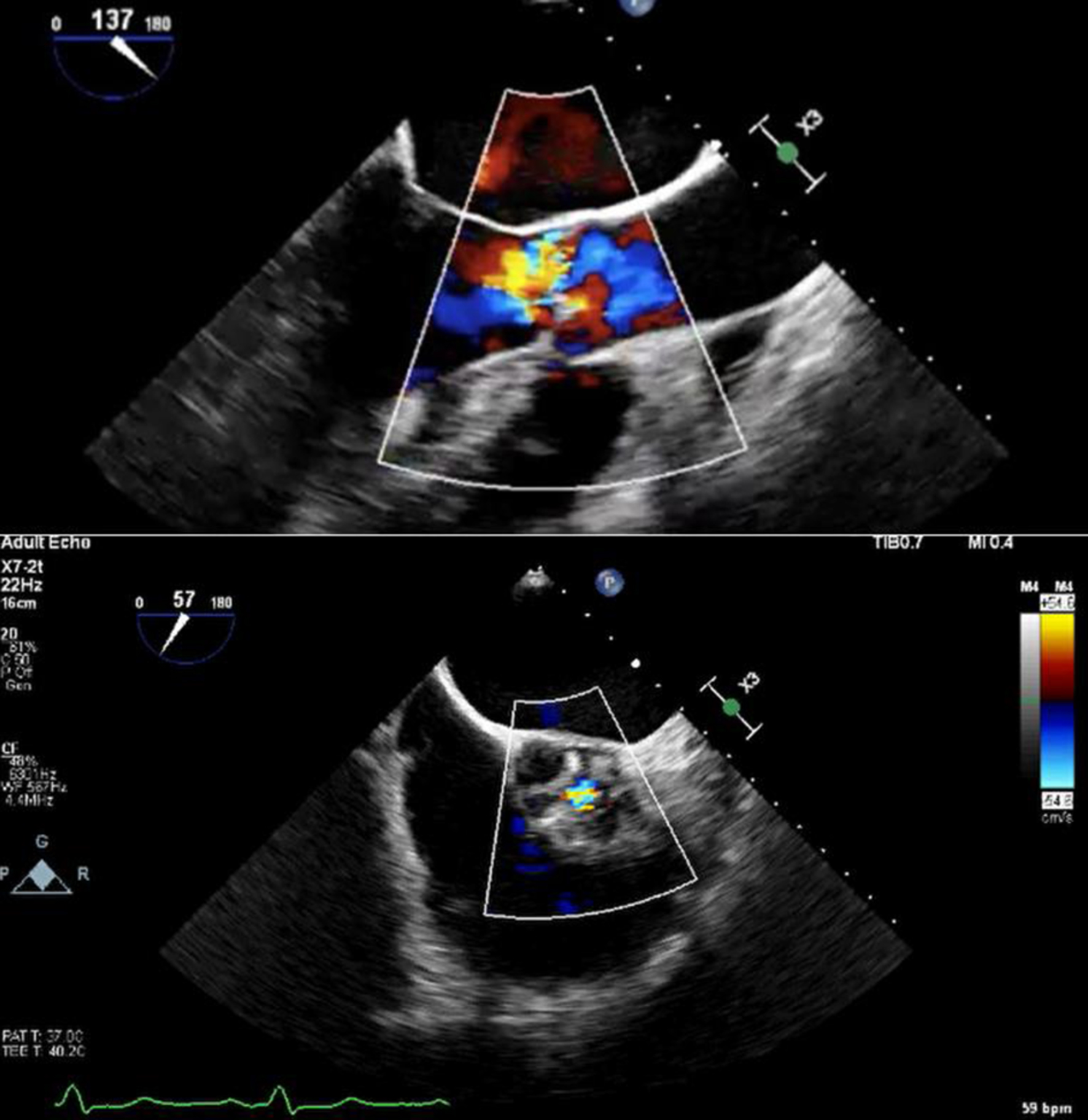

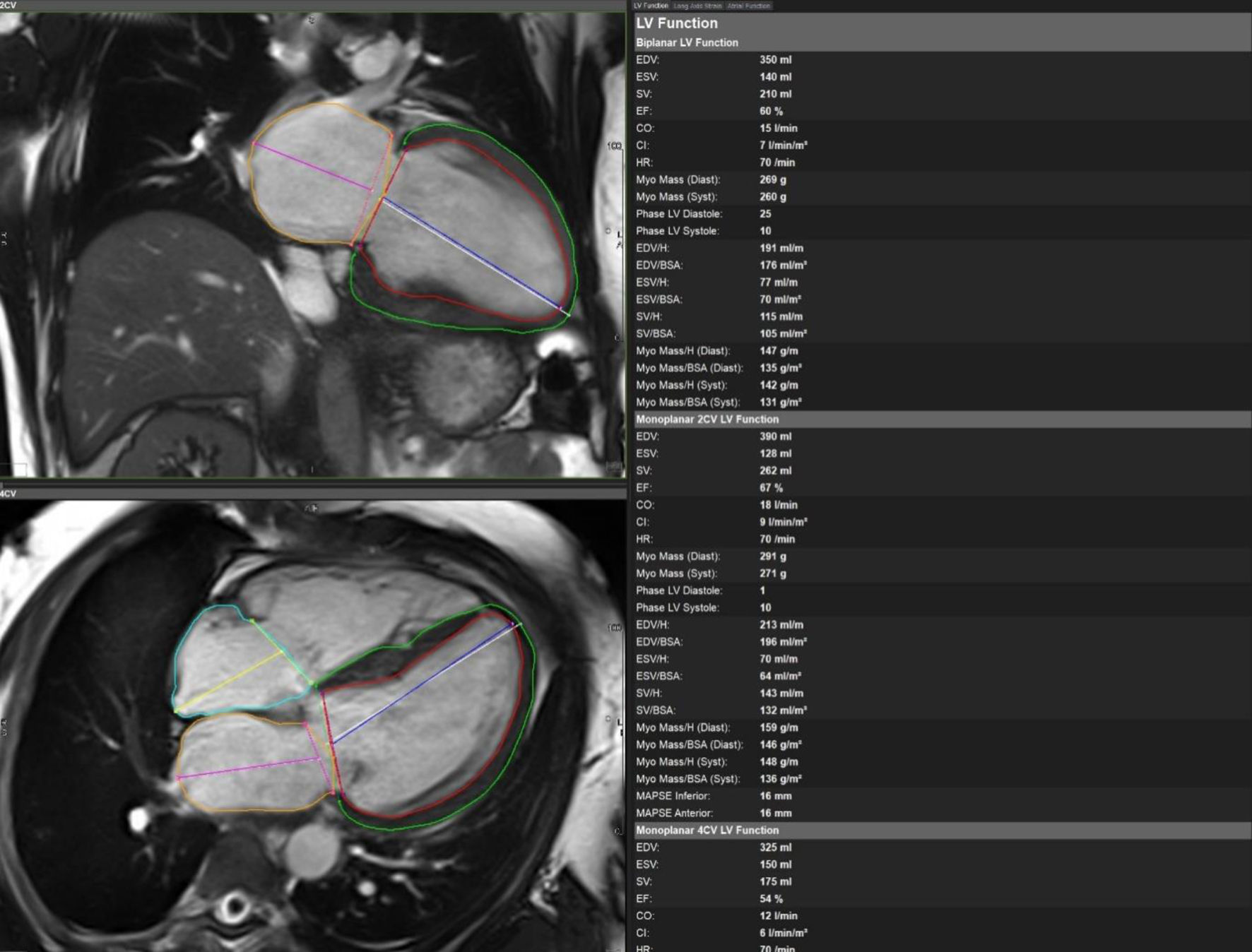

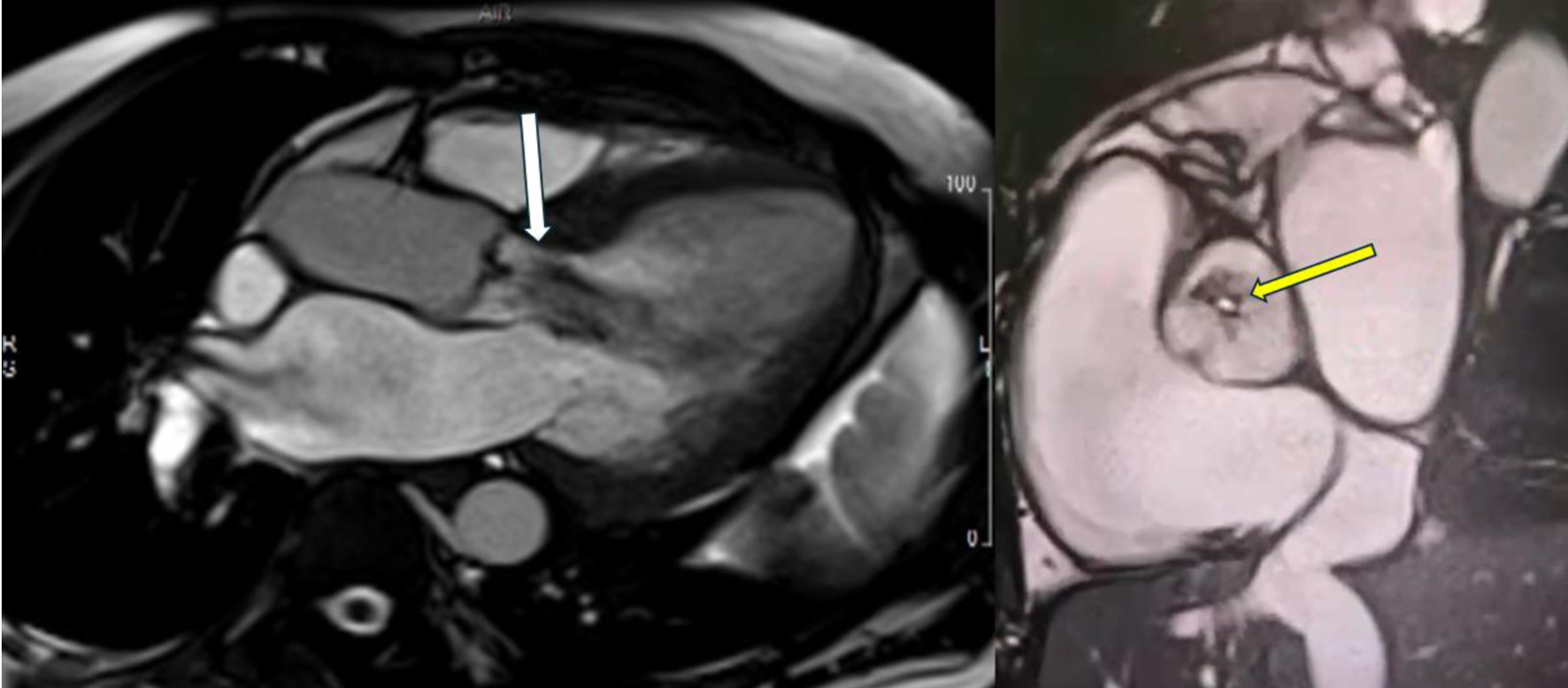

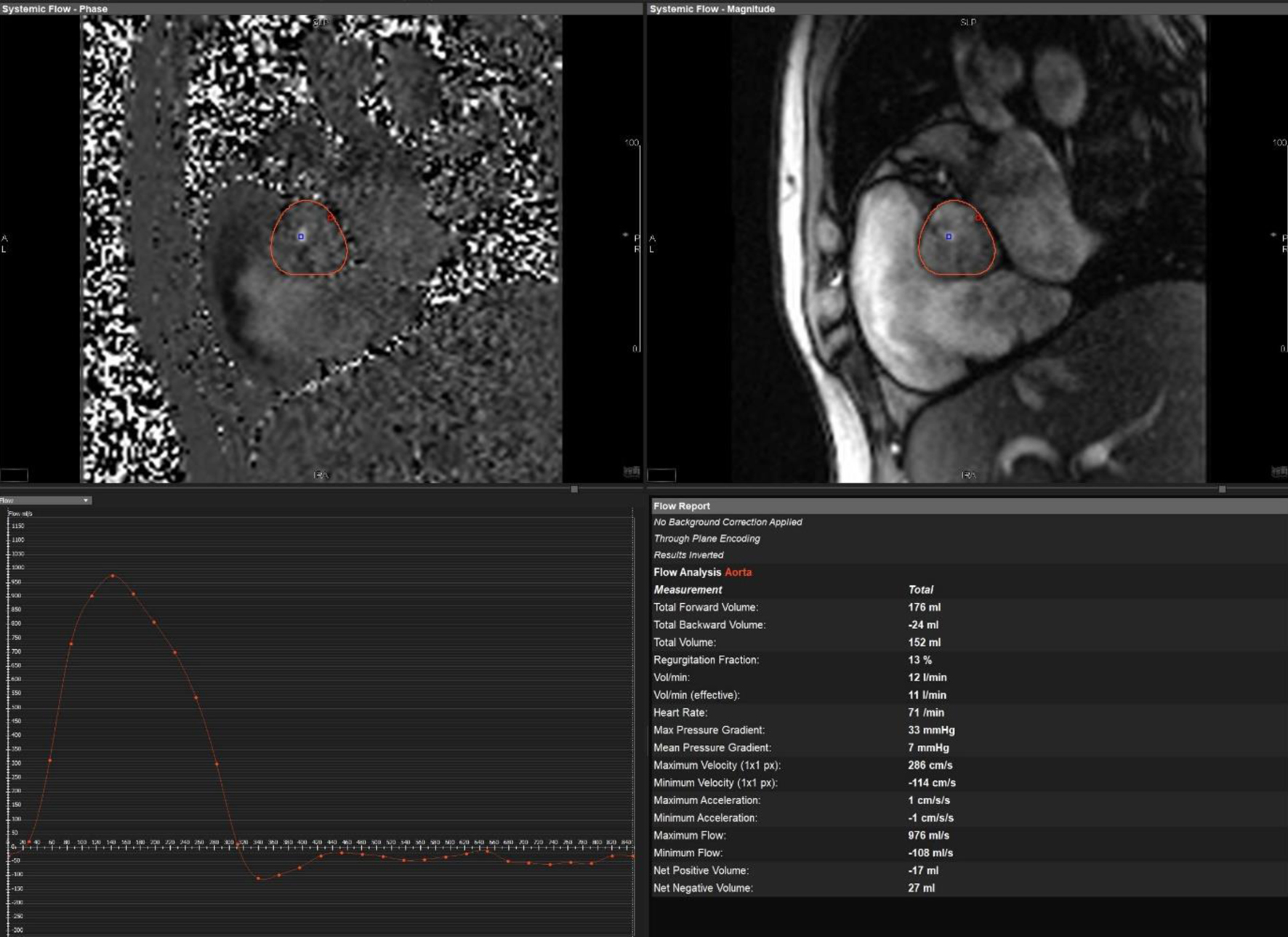

Initial bedside echocardiogram, done while intubated in ICU, showed LVEF of 30-35%, dilated LV at 6 cm, and a central jet of AR deemed moderate. Departmental TEE corroborated the impression of moderate AR. Quantitative assessment was, however, limited by eccentric AR jet (Fig. 1). Coronary angiogram showed no obstructive coronary artery disease. Two weeks later, CMRI showed a severely dilated LV with indexed end diastolic volume of 176 mL/m2 (Fig. 2). There was moderate eccentric LV hypertrophy, but preserved LVEF at 56% and stroke volume of 197 mL. Aortic valve images demonstrated a trileaflet aortic valve with partial fusion of the left and right coronary cusps, and severe AR due to failure of coaptation between these cusps (Fig. 3). Aortic regurgitant fraction was 45-50% by LV-RV stroke volume difference. Unfortunately, flow analysis was limited as the imaging plane was placed on the aortic valve rather than the sino-tubular junction, which would underestimate regurgitant fraction (Fig. 4). The AR was felt to be severe based on qualitative assessment, large, holodiastolic jet extending into LV, aortic diastolic flow-reversal, and regurgitant fraction > 45% plus LV dilatation. There was no systolic anterior motion or LVOT obstruction, and no late-gadolinium enhancement, suggesting no myocardial fibrosis, infiltration, or infarction. There was no fibrosis detected on T1 mapping. Discrepancy in LVEF between imaging modalities was explained by myocardial stunning post-arrest. AR severity was underestimated on echocardiography due to the eccentricity of the AR jet.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Color Doppler transoesophageal echocardiography showing eccentric aortic regurgitation jet, with short-axis view showing regurgitant jet through coaptation defect. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with biplane left ventricular volumes and function. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing severe aortic regurgitation. Long-axis view showing large central aortic regurgitation jet (white arrow) with dilated left ventricular diameter. Short-axis view showing coaptation failure between the left and right coronary cusps (yellow arrow), contributing to severe aortic regurgitation. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing flow across aortic valve. Malalignment of the imaging plane resulted in underestimation of the regurgitant fraction. |

After Heart Team discussion, the patient proceeded to surgical bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement. Intra-operative documentation noted left and right coronary cusp fusion with a large gap between fused leaflets, corresponding with MRI description. He had concurrent left atrial appendage occlusion device insertion. He subsequently had a dual-chamber implantable cardiac defibrillator inserted. Cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillation (CRT-D) was not implanted as a high pacing burden was not anticipated, but the option for later upgrade was considered if LVEF did not improve on optimal medications.

Admission was complicated by development of atrial fibrillation and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, for which he was given amiodarone. He subsequently became clinically and biochemically hyperthyroid. Following consultation with endocrinology, he was started on carbimazole, prednisolone, and propranolol. He also had a large left-sided pleural effusion which necessitated insertion of a chest drain. Pleural aspirate biochemistry was consistent with transudative effusion and attributed to heart failure.

Following surgery, the patient’s LVEF was 25%. There were no echocardiographic signs of high-output heart failure, which may have been due to amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. He was started on guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure. He had early outpatient clinic follow-up arranged with heart failure, cardiothoracic surgery, and endocrinology. On last review, the patient was recovering well with no symptoms attributable to valvulopathy. Repeat echocardiography showed an improved LVEF to 57%.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case highlights the difficult of treatment decisions in cases of borderline severity AR. Despite severe AR on CMRI, echocardiographic parameters indicating moderate regurgitation and the patient’s stable clinical condition, resulted in pursuit of an active surveillance strategy with repeat outpatient echocardiograms. The resulting untreated severe AR and LV remodeling lead to cardiac arrest and subsequent substantial morbidity, which may have been avoided by earlier recognition of AR severity. Indeed, despite some discrepancies between imaging modalities, there was evidence that the AR severity warranted surgical intervention, such as underlying LBBB, NSVT, and LV dilatation.

CMRI provides reproducible and reliable measurements relevant to AR severity grading [3]. CMRI can be used diagnostically in difficult echocardiographic cases, and can provide prognostic information through improved identification of holodiastolic retrograde flow [4]. Importantly, CMRI can reclassify AR severity which potentially leads to earlier intervention [4]. Even without severe AR, CMRI can identify patients who are likely to progress to symptomatic AR or require surgery [5]. CMRI measures of AR severity and LV remodeling are associated with progression to negative outcomes due to AR [6, 7]. CMRI-detected LV remodeling can occur at lower thresholds than currently specified by guidelines [8]. Additionally, CMRI has associated symptoms and LV remodeling due to AR at lower severity thresholds than current guidelines, particularly by measuring indexed LV volumes and regurgitant fraction [6].

Despite guidelines, there is evidence to suggest that patients have improved long-term outcomes with earlier intervention for AR [9]. Patients with class I indications for aortic valve intervention had worse outcomes compared to those with class II indications, which suggests that the AR-induced LV dysfunction intrinsic to class I indications should be pre-empted through earlier intervention. Importantly, the above patient would have been identified by these criteria given his raised indexed LV diastolic volume and regurgitant fraction. Ultimately, however, CMRI is not perfect and has substantial limitations, though still provides important additional information to that obtained via echocardiography. In future, CMR is likely to have a more prominent role in quantifying AR severity and decisions on treatment, especially measurement of regurgitant fraction.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of early detection of severe AR in order to prevent negative outcomes due to LV remodeling. CMRI provides increased resolution compared to echocardiography. In future, CMRI will likely have a more prominent role in quantifying AR severity and decisions on treatment. Used with echocardiography, CMRI can provide additional information to quantify AR severity and LV remodeling, especially in ambiguous cases.

Learning points

Severe AR can lead to catastrophic outcome if not treated appropriately.

CMRI will likely have a more prominent role in quantifying AR severity and decisions on treatment in future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the doctors, radiographers, nurses, technicians, or coordinators who contributed in a supportive role. We are grateful to the patient for consenting to the publication of this case.

Financial Disclosure

No financial support was obtained for this paper, and there are no conflicts to disclose.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Informed Consent

The patient has consented to use of their case history, investigations, and images as part of this case report, in accordance with COPE guidelines.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in direct care of the patient, collection of data, drafting and editing the text, general supervision of the writing process, and approval of the final published version. Philip Nolan and Bridog Nic Aodhabhui were primarily responsible for initial drafts and subsequent editing. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The corresponding author is Philip Nolan.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Writing Committee Members, Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, 3rd, Gentile F, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(4):e25-e197.

doi pubmed - Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, Capodanno D, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2022;75(6):524.

doi pubmed - Nanavaty D, Patel B, Mankad S, Anand V. Aortic regurgitation: diagnosis and evaluation. current treatment options. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2023:1-5.

doi - Kammerlander AA, Wiesinger M, Duca F, Aschauer S, Binder C, Zotter Tufaro C, Nitsche C, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in aortic regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(8 Pt 1):1474-1483.

doi pubmed - Myerson SG, d'Arcy J, Mohiaddin R, Greenwood JP, Karamitsos TD, Francis JM, Banning AP, et al. Aortic regurgitation quantification using cardiovascular magnetic resonance: association with clinical outcome. Circulation. 2012;126(12):1452-1460.

doi pubmed - Malahfji M, Crudo V, Kaolawanich Y, Nguyen DT, Telmesani A, Saeed M, Reardon MJ, et al. Influence of cardiac remodeling on clinical outcomes in patients with aortic regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(19):1885-1898.

doi pubmed - Hashimoto G, Enriquez-Sarano M, Stanberry LI, Oh F, Wang M, Acosta K, Sato H, et al. Association of left ventricular remodeling assessment by cardiac magnetic resonance with outcomes in patients with chronic aortic regurgitation. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(9):924-933.

doi pubmed - Vejpongsa P, Xu J, Quinones MA, Shah DJ, Zoghbi WA. Differences in cardiac remodeling in left-sided valvular regurgitation: implications for optimal definition of significant aortic regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(10):1730-1741.

doi pubmed - de Meester C, Gerber BL, Vancraeynest D, Pouleur AC, Noirhomme P, Pasquet A, de Kerchove L, et al. Do guideline-based indications result in an outcome penalty for patients with severe aortic regurgitation? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(11 Pt 1):2126-2138.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.