| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, October 2025, pages 000-000

Fetal Ovarian Cysts in Prenatal Imaging: Diagnostic Challenges and Management Options

Nikoleta Stoyanovaa, Angel Yordanovb, c, Nikola Popovskia

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medical University Pleven, Pleven, Bulgaria

bDepartment of Gynaecological Oncology, Medical University Pleven, Pleven, Bulgaria

cCorresponding Author: Angel Yordanov, Department of Gynaecological Oncology, Medical University Pleven, Pleven, Bulgaria

Manuscript submitted July 22, 2025, accepted September 22, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: Fetal Ovarian Cysts in Prenatal Imaging

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5173

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Fetal ovarian cysts (FOCs) are a rare prenatal finding that may be associated with maternal, fetal, or neonatal complications. They are classified by various features - small or large, simple or complex, unilateral or bilateral - which determine whether active treatment or simple observation is required. Prenatal ultrasound enables diagnosis as early as the first trimester, though most cases are detected in the second or third trimester. We present a case of a simple, small FOC diagnosed at 27 weeks of gestation in primigravida without accompanying diseases. The cyst remained uncomplicated throughout pregnancy and after birth, with spontaneous regression observed within the first year of life. We also conducted a brief literature review on the management of different types of FOCs. Small, asymptomatic FOCs detected in the second or third trimester usually require only ultrasound monitoring, as most regress spontaneously within the first year after birth. Symptomatic neonatal ovarian cysts, as well as those that enlarge during follow-up in pregnancy, carry a risk of ovarian torsion and generally require surgical intervention. Complex cysts and large cysts may be monitored conservatively unless they cause symptoms or show growth on serial ultrasounds.

Keywords: Fetal ovarian cysts; Ultrasound; Prenatal diagnosis

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Intra-abdominal cysts in the fetus represent a diagnostic challenge, as they may originate from a variety of anatomical structures, including the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, mesenteric, hepatic, and biliary systems. Among these entities, fetal ovarian cysts (FOCs) are the most common cystic formations observed in female fetuses during prenatal life, with an estimated incidence of approximately 1 in 2,500 live births [1]. Although the pathophysiology of ovarian cysts is not yet fully understood, they are generally considered benign functional anomalies. These cysts often result from excessive stimulation of the fetal ovaries by maternal and placental hormones such as maternal estrogens, fetal gonadotropins, and placental human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) [2]. They are more frequently observed in pregnancies complicated by maternal conditions such as diabetes, preeclampsia, or rhesus isoimmunization [3].

While the prognosis is favorable in the majority of cases, careful prenatal evaluation and follow-up are essential, as complications such as torsion, rupture, or compression of adjacent structures may occur in isolated cases. For this reason, early recognition and accurate interpretation of these cysts are crucial for determining optimal management and ensuring the best possible outcomes.

We present a case of a prenatally diagnosed simple FOC that was managed through active monitoring and remained uncomplicated both before and after birth. The cyst was observed in a first, uneventful pregnancy, which was completed via cesarean section due to pelvifetal disproportion.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 26-year old woman, primigravida, had received prenatal care since the 13th week of gestation. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable for medication use, allergies, or any underlying conditions. A routine ultrasound at the 17th week of gestation showed a female fetus with normal size. A fetal morphology scan at the 22nd week of gestation revealed appropriate fetal growth without structural abnormalities.

Diagnosis

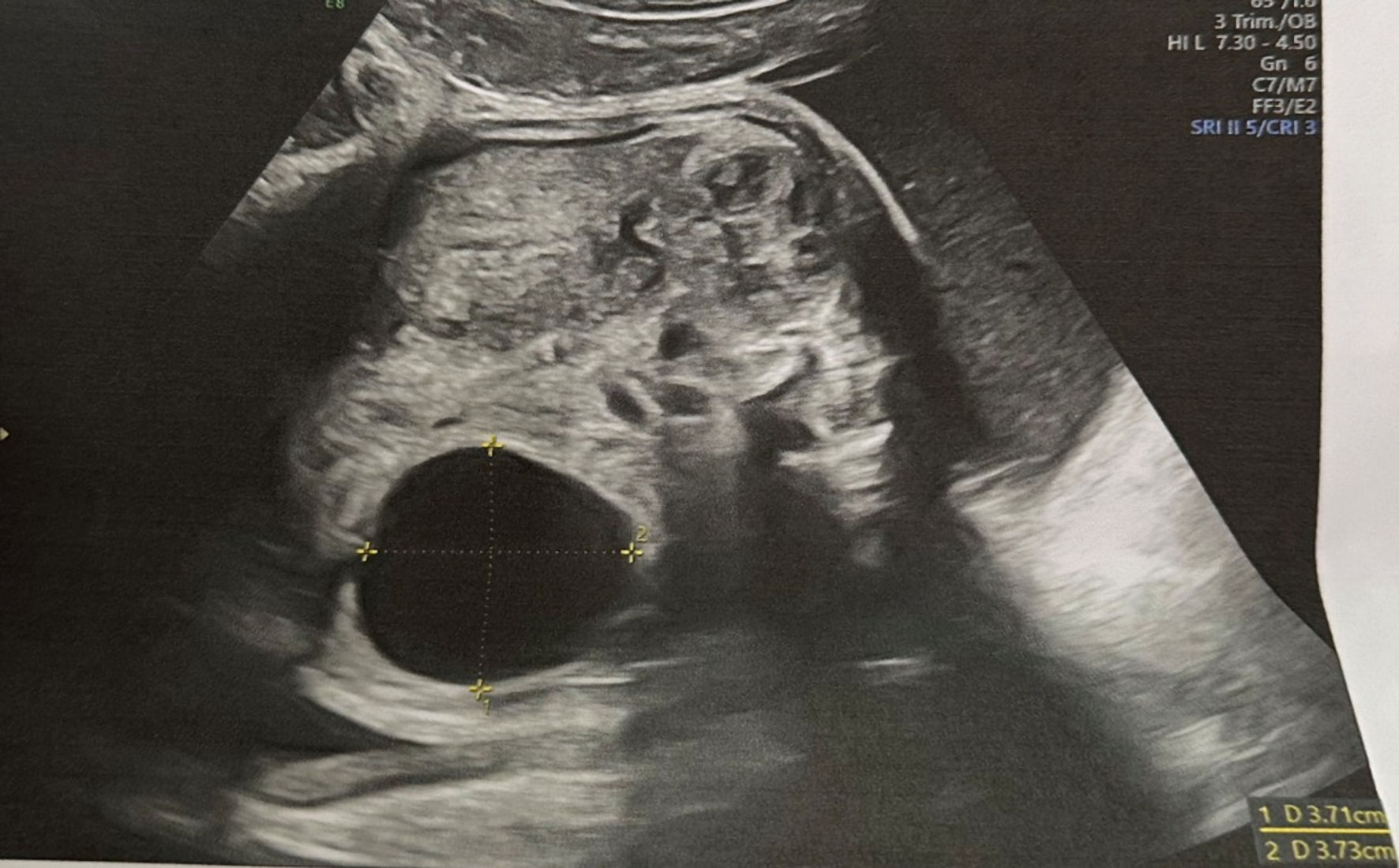

A repeat sonography at 27 weeks noted a fetal abdominal cyst. The patient was referred for comprehensive evaluation and management. A specialist of fetal medicine confirmed the presence of fetal cystic formation in the lower abdomen. The examination revealed female gender with normal biometry, normal appearance of kidneys, urinary bladder and gastrointestinal tract. A left-sided unilocular thin-walled cyst was identified separate from stomach and kidneys. The measurements of the cyst were 37 × 37 mm (Fig. 1). The volume of amniotic fluid was within the normal range, and no hydropic changes were observed in the fetus.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Simple thin-walled cystic formation localized separately from kidney seen in 27th week of gestation. |

Due to the specific ultrasound image and localization of the formation, normal appearance of gastrointestinal and urinary tracts, and the female gender of the fetus, a diagnosis of simple ovarian cyst was made.

Follow-up and outcomes

Serial ultrasound examinations revealed no change in the cyst dimensions, with normal fetal growth for the corresponding gestational age. Delivery was performed by cesarean section at 38 weeks of gestation due to pelvifetal disproportion caused by a second-degree contracted pelvis of the mother. The newborn weighed 3,100 g, with good early adaptation and an excellent Apgar score. Postnatal ultrasound confirmed the presence of a left-sided ovarian cyst measuring 30 × 30 mm. Serial ultrasound follow-ups during the first 6 months demonstrated a gradual decrease in the size of the cyst. A follow-up ultrasound performed 1 year after birth showed no residual cystic formations in the lower abdomen or pelvis.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Epidemiology

FOCs are among the most common intra-abdominal cystic lesions in female fetuses. They are typically diagnosed during the third trimester of pregnancy, most often after the 28th week of gestation. Chen et al reported that 87.2% of FOCs were identified after 28 weeks [4], while Rotar et al observed a mean gestational age of 31 weeks at diagnosis [5].

Although rare, first-trimester diagnosis is possible. Passananti et al reviewed 60 cases of fetal abdominal cysts detected during the first trimester, of which 35% were associated with concurrent or late-onset structural anomalies, and 65% were isolated [6]. Khalil et al described 14 cases diagnosed between 11 and 14 weeks, noting that about 80% of isolated cysts resolved spontaneously during pregnancy [7]. Garcia-Aguilar et al, however, reported a higher rate of associated anomalies when diagnosis occurred in the first trimester [8]. These findings suggest that earlier detection may carry a higher likelihood of underlying pathology, whereas most cysts identified later in gestation are isolated and benign.

Imaging presentation

Ultrasonography plays a fundamental role in the evaluation of FOCs as it remains the primary and most effective diagnostic method. The “daughter cyst sign’’ is considered pathognomonic of ovarian cyst and refers to an eccentric smaller cyst within a large cyst [9]. The reported sensitivity is 82%, with a specificity and positive predictive value of 100% [10].

However, if the ultrasound results are unclear or there is concern about additional fetal structural abnormalities, a fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be advised to achieve a more precise and early diagnosis [3, 11].

МRI plays an established role in the evaluation of fetal anomalies, particularly in cases involving complex neoplasms. However, its significance in the assessment of FOCs remains limited and somewhat controversial. While MRI can offer detailed anatomical information and assist in the differentiation of complex masses in pediatric and adult populations - often influencing treatment decisions - its utility in the prenatal setting for ovarian cysts is generally considered secondary to ultrasound. In most cases, prenatal ultrasound remains the primary imaging modality for diagnosis, given its accessibility, safety, and dynamic assessment capabilities. MRI may be considered in selected cases, particularly when ultrasound findings are inconclusive or when there is suspicion of complications such as hemorrhage or torsion. Nevertheless, the overall impact of MRI on the prenatal management and clinical outcomes of FOCs appears minimal, and its use is typically reserved for specific diagnostic dilemmas [1, 12].

Ovarian cysts may be unilateral or bilateral and may have different ultrasound images. Back in 1988, Nussbaum et al classified ovarian cysts as simple and complex due to their ultrasonographic characteristics [13]. Simple cysts are usually anechoic, unilocular, round and thin-walled. In contrast, complex ovarian cysts are characterized by thickened walls and heterogeneous internal contents, often due to intracystic hemorrhage, septations, or mural nodules. These cysts are associated with a higher risk of complications and are more likely to be symptomatic [13, 14]. Another classification method divides ovarian cysts into small and large, using 40 mm as the cut-off point. Cyst size is a critical factor for future management, as the risk of complications increases proportionally with increasing size. However, ovarian cysts are rarely larger than 100 mm.

The diagnosis FOCs should be considered in a female fetus with a cystic structure in the pelvis or lower abdomen and normal urinary and gastrointestinal tracts [15]. Sometimes polyhydramnios or ascites (as a result from transudation) can be observed due to compression of digestive tube, especially in larger cysts [11, 16]. However, they can also be identified incidentally during routine prenatal ultrasound conducted in the first, second, or third trimesters. Despite advances in prenatal care and access to specialized diagnostic tools, in some cases ovarian cysts may not be detected until birth - either incidentally or due to appearance of related symptoms. The most common symptoms arise from the pressure exerted by the intraabdominal mass.

In adult gynecology, the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) group has introduced standardized terminology and descriptors for adnexal masses, facilitating reproducibility and clinical decision-making. While some of these descriptors, such as “simple” versus “complex” cyst, can be applied in the fetal and neonatal setting, others (e.g., papillary projections or irregular solid areas) may be less relevant or more challenging to assess with prenatal ultrasound. This highlights the current lack of a dedicated, standardized classification system for FOCs and underscores the importance of clear and consistent terminology in clinical practice and research.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of FOCs continues to pose difficulties and includes wide spectrum of intraabdominal formations. Accurately identifying the origin of fetal abdominal cyst requires considerations of the following aspects: the cyst’s location and its relationship with adjacent organs, its morphology and thickness of the wall, the presence of internal contents, fixation or motility and follow-up observation.

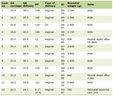

Table 1 [17-22] summarizes key differential diagnoses such as choledochal cyst, intestinal duplication cyst, mesenteric cyst, urachal cyst, lymphangioma, duodenal atresia, and hydrometrocolpos.

Click to view | Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of Fetal Abdominal Cysts |

Although neoplastic causes such as cystadenoma or granulosa cell tumor have been reported [23-25], malignancy is exceedingly rare, with only a single neonatal case described [26]. Thus, differentiating ovarian cysts from other cystic abdominal masses is more clinically relevant for management than excluding malignancy.

Risk factors and complications

Most small, simple cysts are asymptomatic and resolve spontaneously either during pregnancy or within the first year of life [27]. Complications are uncommon, but larger or complex cysts carry a higher risk. Rare complications include torsion, intracystic hemorrhage, rupture with hemoperitoneum, or compression of adjacent structures, which in exceptional cases may require emergency surgical intervention [14]. Very large cysts may exceptionally cause respiratory distress due to diaphragmatic elevation and pulmonary hypoplasia.

Bascietto et al reported ovarian torsion in 44.9% of prenatally diagnosed complex cysts [3]. In isolated cases, a necrotic torsed ovary has caused bowel obstruction or urinary tract compression [2]. Intracystic hemorrhage may rarely lead to fetal anemia, in which case Doppler assessment of the middle cerebral artery can be useful [23]. Despite these reports, serious complications remain the exception rather than the rule.

Management and follow-up

When diagnosed prenatally, ovarian cysts may differ in behavior, management, and prognosis depending on the gestational age at diagnosis.

First-trimester FOCs are rare and should prompt careful evaluation by a fetal medicine specialist. Detailed ultrasound assessment of the cyst and the rest of fetal anatomy is recommended, and karyotyping may be considered if additional anomalies are present. In most cases of isolated cysts, expectant management with close surveillance is appropriate, as many cysts resolve spontaneously without the need for prenatal or postnatal intervention.

Isolated small, asymptomatic FOCs diagnosed in second or third trimester of pregnancy generally require only follow-up with serial ultrasonographic examinations. In the majority of cases, they regress spontaneously within a year after birth, regardless of their sonographic appearance, as shown in our case [27]. Nevertheless, simple cysts can progress to complex cysts during pregnancy, which increases the risk of ovarian loss. Therefore, the right management of simple cysts is important.

Although fetal aspiration has been utilized in the management of larger ovarian cysts, its clinical benefits remain unproven [28, 29]. This approach may be more justifiable in rare cases where the cyst exerts significant pressure on surrounding organs, such as the bowel, leading to potential complications like obstruction or polyhydramnios. However, such scenarios are rare.

Based on their findings, Hara et al proposed diagnostic guidelines for the identification of FOCs. They recommend intrauterine aspiration only for simple FOCs larger than 30 - 40 mm, while suggesting pre- and postnatal observation for smaller simple cysts or complex cysts, given the higher risk of ovarian torsion in these cases [23].

Therapeutic approaches for ovarian fetal and neonatal cysts are still controversial. A recent study indicated that simple cysts measuring less than 50 mm detected on postnatal imaging tend to resolve spontaneously and may be safely monitored through serial ultrasound evaluations [30]. Conversely, due to the risk of hemorrhage, rupture, or bowel obstruction, several studies have advocated for prompt surgical management of neonatal cysts exhibiting complex features [24, 31, 32].

ISUOG advises monitoring simple cysts < 40 mm and considering aspiration for those > 40 mm [33]. The Fetal Medicine Foundation suggests follow-up every 4 weeks and aspiration for cysts > 60 mm [34]. The European Pediatric Surgeons’ Association recommends surgical intervention within the first 2 weeks after delivery for simple cysts > 40 mm or for any complex cyst [35].

Despite these guideline-based recommendations, the majority of small, simple FOCs regress spontaneously either before or shortly after birth and do not require surgical intervention. Serial ultrasound monitoring is generally sufficient for these cases, allowing safe observation while minimizing unnecessary procedures.

Another important aspect is the timing and mode of delivery in cases of FOCs, as spontaneous regression during pregnancy is possible. Determining the optimal time for delivery is crucial to preserve ovarian tissue and function. Early termination of pregnancy may lead to unnecessary postnatal interventions or surgeries, which could have been avoided if spontaneous regression had occurred in the following weeks of gestation.

Spontaneous vaginal delivery is recommended whenever conditions allow [3, 36]. Iatrogenic preterm delivery by cesarean section may be considered in cases of fetal anemia due to intracystic hemorrhage or in the presence of bilateral ovarian cysts larger than 40 mm in diameter [23]. Delivery in a facility with tertiary-level neonatal care is strongly advised.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis of FOCs is favorable. The majority regress spontaneously either before birth or within the first year of life, irrespective of their sonographic appearance [16]. The key determinant of long-term outcome is ovarian salvage, as torsion can result in loss of ovarian tissue. Reported rates of ovarian preservation vary, but timely recognition and appropriate management maximize the chance of preserving reproductive potential.

Conclusions

We presented a clinical case of a prenatally diagnosed simple ovarian cyst that regressed spontaneously after birth without complications. Due to the rarity of this condition, there is still no clear consensus regarding its optimal management. It is essential for clinicians to accurately distinguish ovarian cysts from other abdominal cystic lesions, as their clinical course, prognosis, and management strategies may differ significantly.

Early and accurate diagnosis, combined with individualized follow-up strategies, remains crucial to prevent unnecessary interventions while ensuring timely management of potential complications such as torsion or hemorrhage. Multidisciplinary collaboration between obstetricians, neonatologists, and pediatric surgeons is recommended to achieve the best possible outcomes in such cases.

Learning points

FOCs are relatively rare in the prenatal population. Although complications such as torsion, hemorrhage, or rupture can occur, these events are uncommon, and most cysts resolve spontaneously without intervention. Prenatal ultrasound is the primary diagnostic tool, capable of detecting FOCs as early as the first trimester, though most are found later in pregnancy. The case illustrates a clear example of successful conservative management, avoiding prenatal intervention or postnatal surgery, which is often considered for cysts > 40 mm. The favorable outcome supports current literature suggesting that many simple FOCs can be safely monitored rather than surgically treated.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This research received no external funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AY and NS. Methodology: NS and NP. Formal analysis: NS. Investigation: NP and NS. Resources: NP. Data curation: NS. Writing - original and draft preparation: NS. Writing - review and editing: AY. Visualization: NS. Supervision: AY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy concerns.

| References | ▴Top |

- Melinte-Popescu AS, Popa RF, Harabor V, Nechita A, Harabor A, Adam AM, Vasilache IA, et al. Managing fetal ovarian cysts: clinical experience with a rare disorder. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(4):715.

doi pubmed - Brandt ML, Helmrath MA. Ovarian cysts in infants and children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2005;14(2):78-85.

doi pubmed - Bascietto F, Liberati M, Marrone L, Khalil A, Pagani G, Gustapane S, Leombroni M, et al. Outcome of fetal ovarian cysts diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound examination: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50(1):20-31.

doi pubmed - Chen L, Hu Y, Hu C, Wen H. Prenatal evaluation and postnatal outcomes of fetal ovarian cysts. Prenat Diagn. 2020;40(10):1258-1264.

doi pubmed - Rotar IC, Tudorache S, Staicu A, Popa-Stanila R, Constantin R, Surcel M, Zaharie GC, et al. Fetal ovarian cysts: prenatal diagnosis using ultrasound and MRI, management and postnatal outcome-our centers experience. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;12(1):89.

doi pubmed - Passananti E, Bevilacqua E, Di Marco G, Felici F, Trapani M, Ciavarro V, Di Ilio C, et al. Management and outcome of fetal abdominal cyst in first trimester: systematic review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2024;64(6):721-729.

doi pubmed - Khalil A, Cooke PC, Mantovani E, Bhide A, Papageorghiou AT, Thilaganathan B. Outcome of first-trimester fetal abdominal cysts: cohort study and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(4):413-419.

doi pubmed - Garcia-Aguilar P, Maiz N, Rodo C, Garcia-Manau P, Arevalo S, Molino JA, Guillen G, et al. Fetal abdominal cysts: predicting adverse outcomes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023;102(7):883-890.

doi pubmed - Singh P, Singh SP, Lal H. Daughter cyst sign in the congenital ovarian cyst. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(6):e243963.

doi pubmed - Quarello E, Gorincour G, Merrot T, Boubli L, D'Ercole C. The 'daughter cyst sign': a sonographic clue to the diagnosis of fetal ovarian cyst. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;22(4):433-434.

doi pubmed - Degani S, Lewinsky RM. Transient ascites associated with a fetal ovarian cyst. Case report. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1995;10(3):200-203.

doi pubmed - Nemec U, Nemec SF, Bettelheim D, Brugger PC, Horcher E, Schopf V, Graham JM, Jr., et al. Ovarian cysts on prenatal MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(8):1937-1944.

doi pubmed - Nussbaum AR, Sanders RC, Hartman DS, Dudgeon DL, Parmley TH. Neonatal ovarian cysts: sonographic-pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1988;168(3):817-821.

doi pubmed - Bucuri C, Mihu D, Malutan A, Oprea V, Berceanu C, Nati I, Rada M, et al. Fetal ovarian cyst - a scoping review of the data from the last 10 years. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(2):186.

doi pubmed - Kahraman NC, Celik OY, Obut M, Arat O, Celikkan C, Iskender C, Celen S, et al. Cysts of the fetal abdomen: antenatal and postnatal comparison. J Med Ultrasound. 2022;30(3):203-210.

doi pubmed - Kwak DW, Sohn YS, Kim SK, Kim IK, Park YW, Kim YH. Clinical experiences of fetal ovarian cyst: diagnosis and consequence. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21(4):690-694.

doi pubmed - Tu CY. Ultrasound and differential diagnosis of fetal abdominal cysts. Exp Ther Med. 2017;13(1):302-306.

doi pubmed - Bishop JC, McCormick B, Johnson CT, Miller J, Jelin E, Blakemore K, Jelin AC. The double bubble sign: duodenal atresia and associated genetic etiologies. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2020;47(2):98-103.

doi pubmed - Acikgoz AS, et al. Fetal abdominal cysts: prenatal diagnosis and management. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale). 2015;5(319):2161-0932.

- Cilento BG, Jr., Bauer SB, Retik AB, Peters CA, Atala A. Urachal anomalies: defining the best diagnostic modality. Urology. 1998;52(1):120-122.

doi pubmed - Deshpande P, Twining P, O'Neill D. Prenatal diagnosis of fetal abdominal lymphangioma by ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17(5):445-448.

doi pubmed - Mallmann MR, Reutter H, Mack-Detlefsen B, Gottschalk I, Geipel A, Berg C, Boemers TM, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of hydro(metro)colpos: a series of 20 cases. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2019;45(1):62-68.

doi pubmed - Hara T, Mimura K, Endo M, Fujii M, Matsuyama T, Yagi K, Kawanishi Y, et al. Diagnosis, management, and therapy of fetal ovarian cysts detected by prenatal ultrasonography: a report of 36 cases and literature review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(12):2224.

doi pubmed - Croitoru DP, Aaron LE, Laberge JM, Neilson IR, Guttman FM. Management of complex ovarian cysts presenting in the first year of life. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26(12):1366-1368.

doi pubmed - Marshall JR. Ovarian enlargements in the first year of life: review of 45 cases. Ann Surg. 1965;161(3):372-377.

doi pubmed - Ziegler EE. Bilateral ovarian carcinoma in a 30 week fetus. Arch Pathol (Chic). 1945;40:279-282.

pubmed - Dimitraki M, Koutlaki N, Nikas I, Mandratzi T, Gourovanidis V, Kontomanolis E, Zervoudis S, et al. Fetal ovarian cysts. Our clinical experience over 16 cases and review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(3):222-225.

doi pubmed - Diguisto C, Winer N, Benoist G, Laurichesse-Delmas H, Potin J, Binet A, Lardy H, et al. In-utero aspiration vs expectant management of anechoic fetal ovarian cysts: open randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52(2):159-164.

doi pubmed - Cass DL. Fetal abdominal tumors and cysts. Transl Pediatr. 2021;10(5):1530-1541.

doi pubmed - Papic JC, Billmire DF, Rescorla FJ, Finnell SM, Leys CM. Management of neonatal ovarian cysts and its effect on ovarian preservation. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(6):990-993; discussion 993-994.

doi pubmed - Dolgin SE. Ovarian masses in the newborn. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2000;9(3):121-127.

doi pubmed - Strickland JL. Ovarian cysts in neonates, children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;14(5):459-465.

doi pubmed - Pelizzo G. Neonatal Ovarian Cysts. In: Lima M, Reinberg O (eds). Neonatal Surgery. Springer, Cham. 2019.

doi - Fetal Medicine Foundation. Ovarian Cyst. Fetal Medicine Foundation. https://fetalmedicine.org/education/fetal-abnormalities/genital-tract/ovarian-cyst. Accessed July 1, 2025.

- Szymon O, Fryczek M, Kotlarz A, Taczanowska-Niemczuk A, Gorecki W. Management of neonatal ovarian cysts: a 10-year single-center experience. Pediatr Surg Int. 2025;41(1):135.

doi pubmed - Trinh TW, Kennedy AM. Fetal ovarian cysts: review of imaging spectrum, differential diagnosis, management, and outcome. Radiographics. 2015;35(2):621-635.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.