| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, August 2025, pages 000-000

Benralizumab in a Patient With Refractory Eosinophilic Endocarditis

Hanna M. Schultza, Daniel Valdesb, Ronald R. Butendieck Jrc, Candido E. Riverad, e

aUniversity of Florida College of Pharmacy, Jacksonville, FL, USA

bCancer Care Pharmacy, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA

cDepartment of Rheumatology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA

dDepartment of Hematology/Oncology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA

eCorresponding Author: Candido E. Rivera, Department of Hematology/Oncology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL 32224, USA

Manuscript submitted July 8, 2025, accepted July 25, 2025, published online August 7, 2025

Short title: Benralizumab in Refractory Eosinophilia

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5168

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a hematologic disorder characterized by an increased absolute eosinophil count (AEC) that can lead to tissue infiltration and damage. Idiopathic HES (iHES) comprises a subset of patients with HES, in which a reactive cause such as infections or an inflammatory process cannot be identified, and clonality is not demonstrable. iHES remains a challenge to treat since there is no specific mutation to target. Interleukin-5 (IL-5) is a cytokine responsible for the proliferation and maturation of eosinophils. Anti-IL-5 and anti-IL-5 receptor therapies represent recent advancements in the management of these disorders. A 25-year-old female developed transient and recurrent visual deficits lasting several minutes at a time. Marked peripheral blood eosinophilia was noted. Over a year, she developed Loeffler’s endocarditis (LE), leading to microvascular ischemic strokes and heart failure due to mitral valve infiltration. The patient needed an urgent mitral valve replacement. Multiple lines of standard eosinophil-lowering agents were tried and appeared ineffective or could not be maximally dosed due to hematologic dose-limiting toxicity. Benralizumab (Fasenra®) is an IL-5 receptor antagonist indicated for eosinophilic asthma and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) but not Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for other HESs. Off-label benralizumab was tried, and her eosinophil count normalized within a week, allowing hemodynamic stability for a mitral valve replacement. After a year of continued bimonthly treatment with off-label benralizumab, her eosinophil count remains within normal limits, resulting in stabilization of her cardiac parameters. Off-label benralizumab treatment was effective in controlling our patient’s eosinophilic counts and preventing further cardiac injury. Benralizumab should be considered earlier in the treatment of LE, particularly when rapid control of the eosinophil count is needed.

Keywords: Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome; Loeffler’s endocarditis; Benralizumab; IL-5; IL-5 receptor antagonist

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) encompasses a diverse group of uncommon white blood cell disorders characterized by an elevated absolute eosinophil count (AEC) that can lead to tissue infiltration and end-organ damage. HES is defined by an absolute eosinophil blood count greater than 1,500 cells/µL and greater than 10% eosinophils on two occasions (at least 1 month apart) and organ damage attributed to hypereosinophilic infiltration with the absence of other disorders or conditions causing organ dysfunction [1, 2]. Primary HES is associated with clonal origin within the myeloid or lymphoid cell pathway. Clonality occurs in about 10% of cases with HES [3]. Secondary, nonclonal eosinophilia is a reactive pathway caused by allergies, infections, drug reactions, auto-immune diseases, or solid-tumor malignancies [3]. Nonclonal eosinophilia accounts for approximately 90% of eosinophilia-related diseases. According to the 2022 World Health Organization and International Consensus Classification Schemes of Eosinophilic Disorders, screening for genetic abnormalities (platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA), platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRB), fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), Abelson tyrosine-protein kinase 1 (ABL1), chromosomal reciprocal translocations, T-cell receptor rearrangement, and flow cytometry) is warranted upon diagnosis to correctly categorize HES origin [2]. Mutations or translocations can guide treatment based on myeloid or lymphoid neoplasm classification. Negative testing warrants further exploration, including bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. Increased bone marrow myeloid blasts (5-19%) are diagnostic of chronic eosinophilic leukemia (CEL) or not otherwise specified (NOS). T-cell receptor rearrangement or in vitro T-cell function assays to analyze cytokine production may help in establishing lymphocyte populations driving hypereosinophilia. If all testing is negative and reactive causes of HES are excluded, the disease is classified as idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (iHES) if organ damage is present.

Corticosteroids are the first-line treatment for iHES, with the option to escalate to second-line therapies. Second-line treatments include hydroxyurea, pegylated interferon alfa, imatinib, mepolizumab, alemtuzumab, and chemotherapeutics such as methotrexate and cyclophosphamide. Unresponsive patients should then be considered for clinical trials or even bone marrow transplantation [2].

HESs can become aggressive, infiltrative disorders. Eosinophils infiltrating the heart can cause Loeffler’s endocarditis (LE), also referred to as eosinophilic myocarditis. LE is a high-morbidity and mortality form of cardiomyopathy that progresses in three stages. The initial acute stage is often asymptomatic, with unremarkable findings on imaging studies, and represents the beginning phase of eosinophilic infiltration with concomitant necrosis and inflammatory damage. In the intermediate stage, thrombosis develops within the damaged endocardium, which can lead to thromboembolic events. In the final stage, overt fibrosis develops, replacing damaged cardiac tissue, leading to restrictive cardiomyopathy with diastolic dysfunction, often requiring mitral valve replacement [4].

A recent review surveyed the clinical profiles of 347 patients with HES and their treatment regimens. Of individuals with HES, approximately 152 (44%) patients were diagnosed with iHES. Cardiac involvement was reported in 64 (42%) of the iHES patients [5].

LE treatment goals include preserving cardiac function, preventing thrombosis, and preventing death by decreasing eosinophil counts, preventing further infiltration into other organs, and avoiding bone marrow transplantation.

The purpose of this case study is to highlight the complex intricacies of pharmacological management of iHES-induced LE and offer additional evidence that benralizumab is a promising agent to use in iHES, potentially an option for earlier eosinophilic control.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

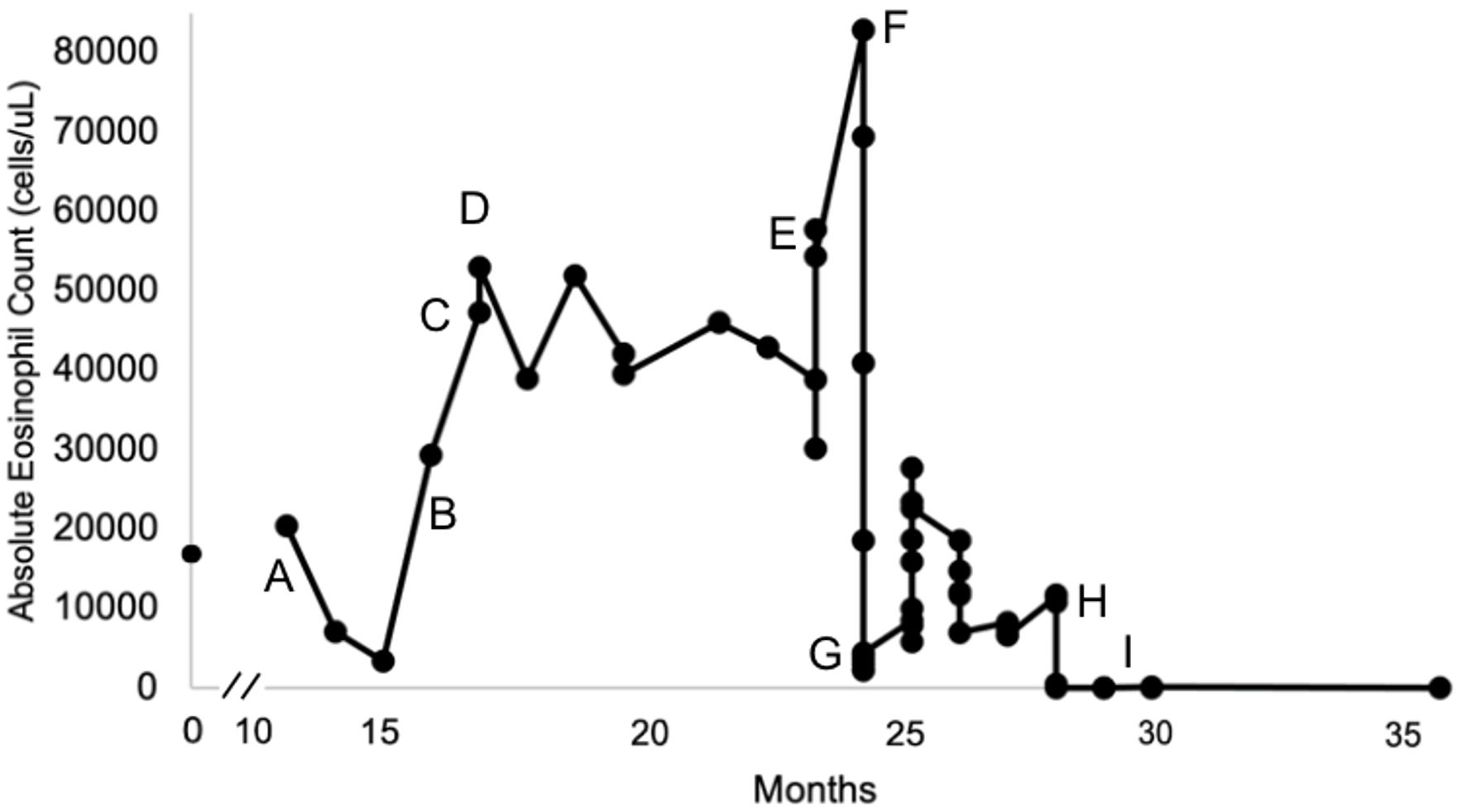

We present a patient who is a 25-year-old female with a past medical history of lightheadedness, vision abnormalities, and syncope since age 18. At age 24, she sought medical attention for transient and recurrent visual deficits lasting several minutes at a time. A markedly elevated AEC was noted in peripheral blood (Fig. 1). Eventually, a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy were performed, which was normocellular with the only significant abnormality of marked eosinophilia. Bone marrow karyotype was normal. Genetic testing revealed a normal karyotype and no abnormalities for JAK2, PDGFRA, PDGFRB, FGFR1, ABL1, or T-cell receptor rearrangement. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was normal. Stool samples were negative for parasitic infection.

Click for large image | Figure 1. The timeline of the patient’s absolute eosinophil counts over 36 months since eosinophilia onset. Pharmacological management and significant events are denoted by the letters A - I. |

Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with secondary hypereosinophilia and managed conservatively for a year until she developed frequent bilateral vision loss and headaches accompanied by worsening shortness of breath and fatigue. An echocardiogram revealed evidence of mitral valve thickening with severe mitral valve regurgitation, concerning for Loeffler’s endocarditis. A mitral valve replacement was recommended once the eosinophil count normalized. A follow-up cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed dilatation of the left ventricle with thickening of the mitral valve leaflets, causing stenosis, eccentric regurgitation, and left atrial dilation. Diffuse subendocardial changes consistent with known eosinophilic endocarditis, such as filling defects in the left ventricular apex, along the medial aspect of the mitral apparatus, adjacent to the interventricular septum, were suggestive of focal areas of post-inflammatory fibrosis rather than thrombi.

Treatment

Initial treatment included high-dose corticosteroids: prednisone 60 mg orally daily (about 1 mg/kg/day), then followed by hydroxyurea 1,000 mg orally daily (Fig. 1, time point A). Hydroxyurea and prednisone combination therapy was titrated to 2,000 mg orally daily and 80 mg orally daily, respectively, over the next 2 months, with a suboptimal response. Prednisone 80 mg orally daily was continued, and an initial trial of mepolizumab 100 mg subcutaneously monthly resulted in continued AEC elevation (Fig. 1, time point B). Prednisone was tapered off, and a single dose of empiric oral ivermectin in addition to continuing mepolizumab 100 mg subcutaneously monthly was shown to be ineffective with increasing AEC (Fig. 1, time point C). An empirical trial of imatinib 400 mg orally once daily was then initiated. The patient was continued on imatinib for approximately 6 months (about 16 - 23 months), and the AEC decreased from 53,000 cells/µL to 30,200 cells/µL at the expense of grade 2-3 [6] neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia (Fig. 1, time point D).

After failing multiple lines of treatment, the patient was referred to our institution for further management (month 12, Fig. 1). Metabolic, autoimmune, infectious, and nutritional causes were ruled out. The diagnosis of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) was considered, but this patient lacked typical EGPA features such as asthma, nasal polyps, chronic rhinosinusitis, pulmonary infiltrates, cutaneous vasculitis findings, mononeuritis multiplex or motor neuropathy. The patient’s perinuclear antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody testing was also negative. The 2022 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for EGPA should be applied when a diagnosis of small-or medium-vasculitis has been made, which was not identified in this patient [7]. While cardiac involvement is a well-recognized and sometimes predominant manifestation of EGPA, particularly in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-negative patients, all published cases series and reviews emphasize that EGPA diagnosis requires a combination of clinical, laboratory and often histopathological features typically including asthma, sinonasal disease, and/or other organ involvement, in additional to eosinophilia and cardiac manifestations, which were not observed in this patient [8-15]. Consequently, Loeffler’s endocarditis associated with HES was deemed a more likely diagnosis.

Shortly after being transferred to our institution, imatinib was discontinued, and a trial of oral methotrexate 10 mg/m2 weekly was started unsuccessfully with a rapid rise of her eosinophil count accompanied by worsening heart failure (Fig. 1, time point E). The patient was hospitalized and was noted to develop multiple microinfarcts on the brain MRI. CT chest with intravenous (IV) contrast raised concern for left ventricular thrombus. Her cardiomyopathy symptoms worsened, requiring hospitalization and intensive care for heart failure and titration of her anticoagulation regimen as tolerated by the platelet count. The patient was then started on high-dose hydroxyurea, initially at a dose of 4,000 mg orally daily in addition to therapeutic anticoagulation (Fig. 1, time point F). When titrating down her dose of hydroxyurea, we could not achieve normalization of eosinophil count without causing grade 3-4 [6] anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia. We then tried a combination of hydroxyurea (1,000 mg orally daily) and mepolizumab (300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks), only achieving a partial response, bringing down the AEC to a nadir of 5,800 cells/µL at the expense of grade 2-3 [6] anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia (Fig. 1, time point G). Partial eosinophilic response to this combination treatment was short-lasting, and the eosinophil count started rising again within a couple of months. Interferon treatment was not tried as the patient was experiencing cytopenias, and we were favoring treatments with a relatively faster clinical response. IV cyclophosphamide was not tried due to concerns of alkylator damage to the bone marrow in the long term in such a young patient.

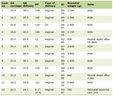

Off-label benralizumab was then started at a dose of 30 mg subcutaneously once every 4 weeks for initial dosing and transitioned to every 8 weeks after the first three doses. Eosinophil counts declined to 560 cells/µL within 5 days and to 0 cells/µL within 12 days (Fig. 1, time point H). Table 1 displays the AEC trends in coordination with pharmacological management.

Click to view | Table 1. Absolute Eosinophil Counts and Treatment Denoted by A - I |

Follow-up and outcomes

Once eosinophilia resolved, the patient was able to proceed with mitral valve replacement surgery, which was uneventful. Mitral valve pathology revealed valvular tissue with degenerative changes and amorphous non-viable material. Eosinophilic infiltration or granulomas were not observed. A heart biopsy was not felt to be indicated by the cardiothoracic surgeon at the time of valve replacement.

A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed for reassessment 9 months after surgery, which showed adequate mitral prosthesis function. While asymptomatic, she continued to have moderate-to-severe tricuspid valve regurgitation and was managed conservatively with diuretics. Repeat imaging reassessment was planned periodically, and if the tricuspid valve regurgitation remains severe, minimally invasive options for therapy will be considered.

The patient continues to be treated with off-label benralizumab and maintains a complete response with the AEC goal of < 500 cells/µL for over a year (Fig. 1, time point I).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Multiple lines of therapy are often required during the initial management of iHES before a complete response is achieved. Recently, developed therapies include the use of monoclonal antibodies such as mepolizumab, dupilumab, atezolizumab, and benralizumab. Benralizumab, an interleukin-5 (IL-5) receptor alpha-directed cytolytic monoclonal antibody, is indicated for adjunctive maintenance treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma aged greater than 6 years and, more recently, approved for EGPA [16]. Benralizumab was granted orphan drug status in the year 2019 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the management of HES [17]. A phase 2 study for the use of benralizumab in PDGFRA-negative HES was published in the year 2019 [18].

We hypothesized that our patient may have markedly elevated IL-5 levels that cannot be neutralized efficiently with high-dose mepolizumab, 300 mg administered subcutaneously weekly, but can be counteracted through anti-IL-5 receptor blockade on the surface of eosinophils by benralizumab. This case is an example of what may be undocumented evidence in iHES that benralizumab may be more effective than mepolizumab. It is substantiated in EGPA that anti-IL5 receptor antibody treatment achieved a higher complete response at 12 months, and a deeper peripheral eosinophil reduction than anti-IL5 antibody treatment [19].

Data are limited for iHES management with cardiac involvement. Targeted monoclonal antibody therapies have become a mainstay for the treatment of eosinophilic asthma.

One case report of a 51-year-old male with uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma and cardiogenic shock was treated with high-dose steroids and benralizumab. Eosinophil count returned to normal, and asthma symptoms improved. An endomyocardial biopsy 26 days later revealed absent infiltration of eosinophils, absent myocardial injury, and mild myocyte hypertrophy [20].

Another case report of hypereosinophilic cardiac infiltration detailed a 19-year-old male with EGPA. Benralizumab returned the eosinophil count to normal. The patient did have cardiac infiltration and showed an increase in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) from 40% upon presentation to 60% after 2 months of benralizumab therapy [21].

Chen et al reported the use of off-label benralizumab in HES. Of the 15 patients treated with benralizumab for any HES subtype, 10 (67%) patients achieved hematological remission, and four (27%) patients were already in remission, and one (6%) patient did not achieve remission on benralizumab. iHES was represented by four (27%) patients in the cohort, and all responded clinically to benralizumab, demonstrating a glucocorticoid-sparing effect [22]. Although no iHES patients had cardiac involvement in this series, the overall utilization of benralizumab is promising.

In another case series, 15 patients with refractory HES were treated with compassionate, off-label benralizumab. Of those, three (20%) patients had iHES with eosinophilic myocarditis refractory to multiple therapies and were then treated with benralizumab, achieving a partial or complete response [23].

Learning points

Off-label benralizumab treatment was effective in controlling our patient’s AEC and preventing further cardiac injury. Benralizumab should be considered earlier in the treatment of LE, particularly when rapid control of the AEC is needed. A phase 3 study (NATRON) to evaluate the efficacy and safety of benralizumab in patients with HES is currently ongoing. This robust study is a double-blind, 1:1 placebo-controlled randomized controlled study in approximately 120 patients [24]. Additionally, a phase 2-3 study aiming to evaluate safety and efficacy of benralizumab in subjects with HES (HESIL5R) is ongoing [25].

This patient’s rare diagnosis and complicated clinical course exemplifies the necessity for multi-disciplinary collaboration. Thomsen et al outlines the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to eosinophilia where patients with persistently increased eosinophil counts and variable symptoms can benefit from a multidisciplinary team at a tertiary center with availability of clinical trials. This process promotes careful consideration of labeled, off-label, or experimental therapies for a rare disease such as iHES, providing additional experience that can enhance treatment algorithms, potentially benefiting future patients with similar disease presentations [26].

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This case report was not funded.

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no conflict of interest do declare.

Informed Consent

Patient’s informed consent for publication of this report was obtained.

Author Contributions

Candido E. Rivera had full access to all the data and analysis in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: all authors. Critical revision of the manuscript: all authors. Administrative and technical support: Hanna M. Schultz. Supervision: Candido E. Rivera.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

HES: hypereosinophilic syndrome; AEC: absolute eosinophil count; iHES: idiopathic HES; IL-5: interleukin-5; LE: Loeffler’s endocarditis; EGPA: eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; PDGFRA: platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha; PDGFRB: platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta; FGFR1: fibroblast growth factor receptor 1; JAK2: Janus kinase 2; FLT3: FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; ABL1: Abelson tyrosine-protein kinase 1; CEL: chronic eosinophilic leukemia; NOS: not otherwise specified; CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

| References | ▴Top |

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, Roufosse F, Gotlib J, Weller PF, Hellmann A, et al. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(3):607-612.e609.

doi pubmed - Shomali W, Gotlib J. World Health Organization and International Consensus Classification of eosinophilic disorders: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2024;99(5):946-968.

doi pubmed - Schwaab J, Lubke J, Reiter A. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome - diagnosis and treatment. Allergo J Int. 2022;31:251-256.

- Salih M, Ibrahim R, Tirunagiri D, Al-Ani H, Ananthasubramaniam K. Loeffler's endocarditis and hypereosinophilic syndrome. Cardiol Rev. 2021;29(3):150-155.

doi pubmed - Requena G, van den Bosch J, Akuthota P, Kovalszki A, Steinfeld J, Kwon N, Van Dyke MK. Clinical profile and treatment in hypereosinophilic syndrome variants: a pragmatic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(8):2125-2134.

doi pubmed - National Cancer Institute (U.S.) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 5.0. National Cancer Institute. 2017.

- Grayson PC, Ponte C, Suppiah R, Robson JC, Craven A, Judge A, Khalid S, et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for rheumatology classification criteria for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(3):309-314.

doi pubmed - Zampieri M, Emmi G, Beltrami M, Fumagalli C, Urban ML, Dei LL, Marchi A, et al. Cardiac involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Churg-Strauss syndrome): Prospective evaluation at a tertiary referral centre. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;85:68-79.

doi pubmed - Sartorelli S, Chassagnon G, Cohen P, Dunogue B, Puechal X, Regent A, Mouthon L, et al. Revisiting characteristics, treatment and outcome of cardiomyopathy in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Churg-Strauss). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61(3):1175-1184.

doi pubmed - Bond M, Fagni F, Moretti M, Bello F, Egan A, Vaglio A, Emmi G, et al. At the heart of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: into cardiac and vascular involvement. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2022;24(11):337-351.

doi pubmed - Garcia-Vives E, Rodriguez-Palomares JF, Harty L, Solans-Laque R, Jayne D. Heart disease in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) patients: a screening approach proposal. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(10):4538-4547.

doi pubmed - Hazebroek MR, Kemna MJ, Schalla S, Sanders-van Wijk S, Gerretsen SC, Dennert R, Merken J, et al. Prevalence and prognostic relevance of cardiac involvement in ANCA-associated vasculitis: eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Int J Cardiol. 2015;199:170-179.

doi pubmed - Cereda AF, Pedrotti P, De Capitani L, Giannattasio C, Roghi A. Comprehensive evaluation of cardiac involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) with cardiac magnetic resonance. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;39:51-56.

doi pubmed - Neumann T, Manger B, Schmid M, Kroegel C, Hansch A, Kaiser WA, Reinhardt D, et al. Cardiac involvement in Churg-Strauss syndrome: impact of endomyocarditis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88(4):236-243.

doi pubmed - Nakayama T, Murai S, Ohte N. Dilated cardiomyopathy with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis in which active myocardial inflammation was only detected by endomyocardial biopsy. Intern Med. 2018;57(18):2675-2679.

doi pubmed - AstraZeneca. FASENRA (benralizumab) injection, for subcutaneous use. 2024. Available from: FDA Drug Database.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Benralizumab Orphan Drug Designations and Approvals. 2025. Available from: FDA Orphan Drug Database.

- Kuang FL, Makiya MA, Ware JM, Wetzler L, Nelson C, Brown T, Khoury P, et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Benralizumab Treatment for PDGFRA-Negative Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2025;13(6):1421-1429.e1422.

doi pubmed - Mattioli I, Urban ML, Padoan R, Mohammad AJ, Salvarani C, Baldini C, Berti A, et al. Mepolizumab versus benralizumab for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA): A European real-life retrospective comparative study. J Autoimmun. 2025;153:103398.

doi pubmed - Goyack L, Garcha G, Shah R, Ortiz Gonzalez Y, Vollenweider M, Salimian M, Cheung W. Rapid effect of benralizumab in fulminant eosinophilic myocarditis in the setting of uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma. J Cardiol Cases. 2023;28(3):100-104.

doi pubmed - Colantuono S, Pellicano C, Leodori G, Cilia F, Francone M, Visentini M. Early benralizumab for eosinophilic myocarditis in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Allergol Int. 2020;69(3):483-484.

doi pubmed - Chen MM, Roufosse F, Wang SA, Verstovsek S, Durrani SR, Rothenberg ME, Pongdee T, et al. An international, retrospective study of off-label biologic use in the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(5):1217-1228.e1213.

doi pubmed - Veltman Y, Aalbers AM, Hermans MAW, Mutsaers P. Single-center off-label benralizumab use for refractory hypereosinophilic syndrome demonstrates satisfactory safety and efficacy. EJHaem. 2025;6(1):e1014.

doi pubmed - AstraZeneca. A phase III study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of benralizumab in patients with Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) (NATRON). ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT04191304. Accessed March 2025. Available from: NATRON Study Record.

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), AstraZeneca. Study to Evaluate Safety and Efficacy of Benralizumab in Subjects with Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HESIL5R). ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT02130882. Accessed July 2025. Available from: HESIL5R Study Record.

- Thomsen GN, Christoffersen MN, Lindegaard HM, Davidsen JR, Hartmeyer GN, Assing K, Mortz CG, et al. The multidisciplinary approach to eosinophilia. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1193730.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.