| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 12, December 2025, pages 510-516

Chronic Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation in Patient With Metastatic Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor: Treating Bleeding With Anticoagulation

Emily Boppa, Zhu Cuib, Jacob Elkonb, c

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA 02111, USA

bDepartment of Hematology/Oncology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA 02111, USA

cCorresponding Author: Jacob Elkon, Department of Hematology/Oncology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA 02111, USA

Manuscript submitted July 5, 2025, accepted August 8, 2025, published online November 28, 2025

Short title: Chronic DIC in Patient With Metastatic GIST

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5164

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is an uncontrolled activation of the coagulation cascade which is often a complication observed in patients with malignancies. DIC can occur in both hematologic and solid malignancies. Management of DIC is often focused on treating the underlying cause and supportive care, which varies based on thrombotic versus bleeding-predominant phenotypes. We report a case of a 69-year-old man with metastatic malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) diagnosed 9 years prior and actively on imatinib, who presented to the emergency department (ED) with gingival bleeding. On presentation, he was hypertensive with active gingival bleeding and was found to have anemia, thrombocytopenia, and mildly elevated coagulation parameters. His initial bleeding was thought to be due to poor dental hygiene and thrombocytopenia, which may be a side effect of imatinib. His imatinib was discontinued, yet he returned to the ED within 2 days with hematuria and melanic stools. He developed multiple sources of bleeding with worsening bicytopenia, progressive coagulopathy, and high levels of fibrin degradation products. He was diagnosed with DIC. He went on to have four additional hospitalizations for bleeding from various sites and abdominal pain. His DIC was attributed to malignancy with findings of disease progression, tumor thrombi, pulmonary embolism, and intracranial hemorrhage through his course. This case represents a rare occurrence of chronic DIC in metastatic GIST and is only the second known report of chronic DIC in a patient with GIST. Despite adjustments to his cancer therapies and anticoagulation, he continued to have episodes of DIC with frequent hospitalizations and ultimately death. Further research is warranted on the selection of and potential variability in bleeding risks of different anticoagulants in DIC. The complexity of tumor-induced coagulopathy and impact of cancer therapies on coagulation highlights the need for additional research into tailored management to improve outcomes in similar cases.

Keywords: Disseminated intravascular coagulation; Gastrointestinal stromal tumor; Tyrosine kinase inhibitor; Thromboembolism; Anticoagulation

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a consumptive coagulopathy that often begins with widespread activation of the coagulation cascade that can result in thrombosis with deposition of fibrin products and then subsequent bleeding from consumption of coagulant proteins and platelets [1, 2]. DIC can be caused by sepsis, trauma, obstetric emergencies, malignancy, both hematologic and solid. Malignancy-related DIC is often less severe than other acute inflammatory processes such as infection or trauma and can even be an initial presentation of the disease. Management of DIC is often focused on treating the underlying cause and supportive care, which varies based on thrombotic versus bleeding-predominant phenotypes [3].

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is a common tumor of mesenchymal origin that arises in the gastrointestinal tract. Molecular changes such as KIT or PDGFRA mutations play an important role in the pathogenesis of these tumors via activation of tyrosine kinase receptors [4]. Localized disease can be treated with surgical resection alone. Patients with high risk of relapse who have KIT mutations are treated with adjuvant tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) [5, 6]. Imatinib is usually used in the first line, though additional TKIs are available for advanced resistance including sunitinib, regorafenib, and ripretinib [4].

This case report details chronic DIC in a patient with metastatic GIST. Through this case we aim to identify potential contributing factors and describe the treatment of DIC with unique considerations, such as anticoagulation selection.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Oncologic history

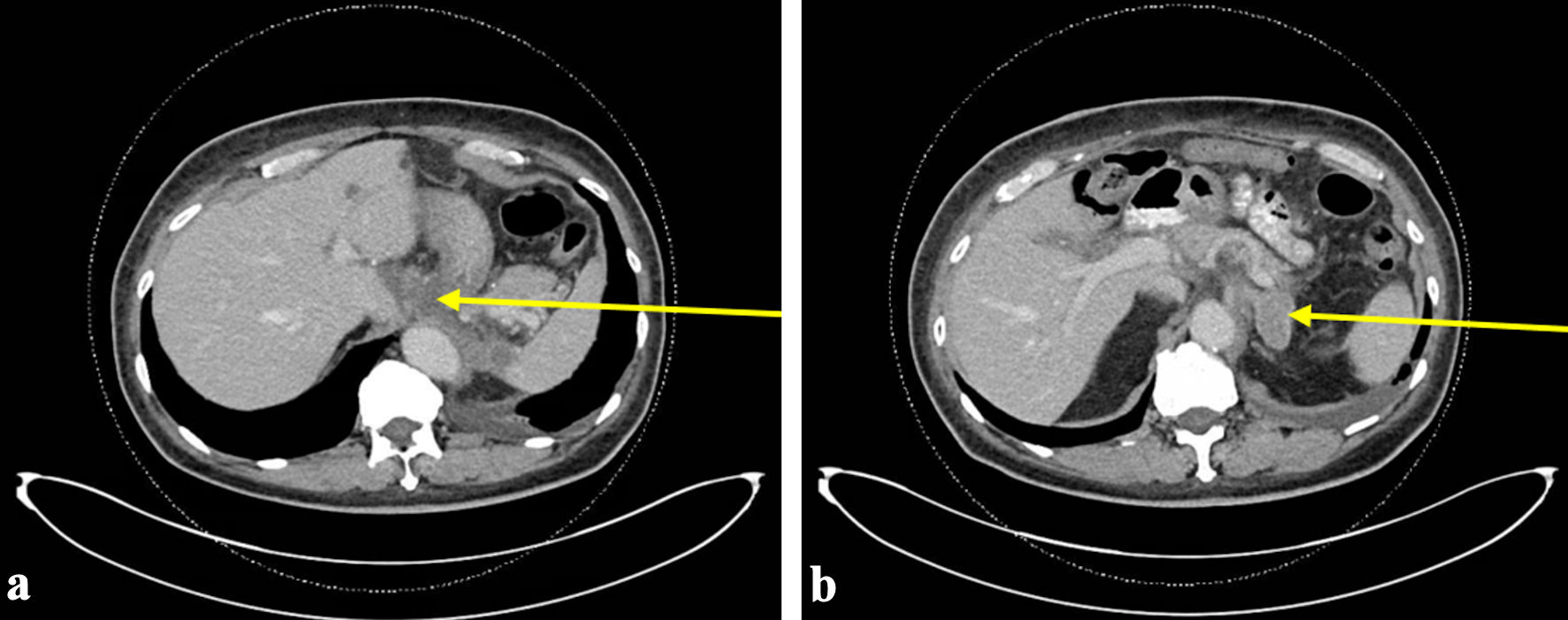

This case is a 69-year-old man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, and metastatic malignant GIST who presented to the emergency department (ED) with gingival bleeding. He was originally diagnosed with GIST 9 years prior to development of DIC, for which his treatment included gastric wedge resection of the primary tumor and 12 months of adjuvant imatinib. Three years prior to developing DIC, he was found to have metastatic recurrence involving the liver and the region adjacent to the gastroesophageal junction. Endoscopic fine needle aspiration was performed on celiac lymph node, which demonstrated GIST, including 11 mitoses per 10 high power field, and Ki-67 of 14%. Next generation sequencing was positive for KIT exon 11 mutation with deletion of Trp557_Lys558 and negative for any PDGFRA mutations. Based on his genotypic information, he was initiated on imatinib 400 mg daily. His case was reviewed by a multidisciplinary tumor board that recommended against surgical intervention for residual disease burden. Shortly prior to developing DIC, a follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated progression of disease with worsening pulmonary nodules, bilateral retroperitoneal adenopathy, soft tissue thickening around esophageal hiatus, and new left adrenal lesion (Fig. 1). Biopsy of adrenal lesion confirmed metastatic GIST. He remained on imatinib 400 mg daily at time of presentation.

Click for large image | Figure 1. The most recent CT abdomen and pelvis performed prior to initial ED visit with bleeding. CT scan at this time demonstrated progression of disease with worsening pulmonary nodules, bilateral retroperitoneal adenopathy, soft tissue thickening around esophageal hiatus (arrow) (a), and new left adrenal lesion (arrow) (b). ED: emergency department; CT: computed tomography. |

Investigations

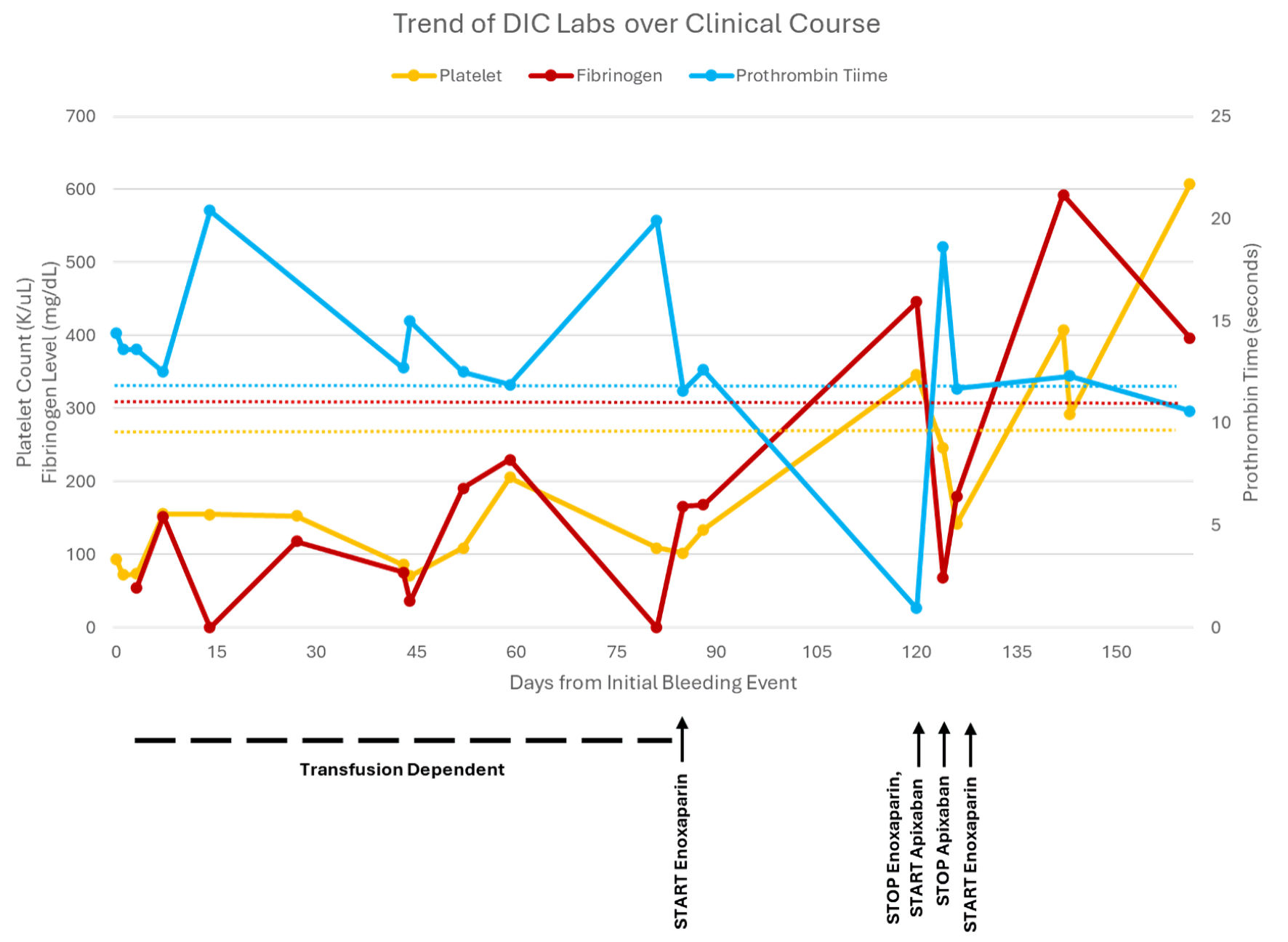

Patient presented to the ED with gingival bleeding that persisted for 1 day after using a toothpick. He denied any bleeding at other anatomical sites, prior use of blood thinners, history of any bleeding disorders or significant hemorrhagic events associated with surgical procedures. Vitals were notable for normal temperature, normal heart rate, and hypertension with blood pressure of 176/99 mm Hg. Physical exam demonstrated active gingival bleeding between lower central incisors, remainder of oropharynx normal, and normal skin. Initial laboratory analysis on presentation with gingival bleeding were notable for hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (normal 13.0 - 17.5) from baseline of 12 - 13.5 g/dL, platelet count of 93 × 103/µL (normal 150 - 400), which had been 229 × 103/µL 2 weeks prior, prothrombin time (PT) of 14.4 s (normal 9.7 - 14.0), international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.25, and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) of 43.7 s (normal 25.7 - 35.7) (Fig. 2). Peripheral blood smear demonstrated scant schistocytes. Patient was discharged from the ED and seen in oncology clinic the following day. Laboratory analysis was repeated with hemoglobin 10.3 g/dL, platelet count 72 × 103/µL, PT 13.6 s, INR 1.18, PTT 40.5 s, and lactate dehydrogenase 356 U/L (normal 110 - 250). Imatinib was discontinued due to concern for thrombocytopenia and bleeding in the setting of poor dental health.

Click for large image | Figure 2. The trend of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) labs from initial bleeding event until patient death, including platelet count, fibrinogen level, prothrombin time (PT), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT). PTT was not included due to simplicity. Additionally, PTT generally correlated with PT except when on enoxaparin and was higher due to enoxaparin once initiated. |

He returned to the ED the following day for new onset hematuria and melanic stools. On exam, he was afebrile, hypertensive with blood pressure 155/87 mm Hg, with trace left lower gingival bleeding, no rash or ecchymosis, external hemorrhoids without active bleeding, brown stool but guaiac positive. Laboratory analysis demonstrated hemoglobin 9.0 g/dL, platelet count 74 × 103/µL, PT 15.5 s, INR 1.34, PTT 44.8 s, fibrinogen 55 mg/dL (normal 170 - 440), D-dimer 64,343 ng/mL fibrinogen equivalent units (FEU) (normal 215 - 500), haptoglobin 11 mg/dL (normal 26 - 240), lactate dehydrogenase 340 U/L, iron panel within normal limits, and reticulocyte index 0.63. Urinalysis showed 3+ blood and 50 red blood cells. He was admitted due to concern for DIC. Patient received one unit of cryoprecipitate and one unit of fresh frozen plasma with stabilization of DIC labs and resolution of bleeding. He was discharged 4 days later with plan to have outpatient urology follow-up for hematuria.

Diagnosis

On his initial presentation to the ED, his bleeding was thought to be due to thrombocytopenia, including drug-induced thrombocytopenia, given active treatment with imatinib. Poor dental health was considered as a contributing factor on first presentation given oral hygiene and inciting event of trauma to gums from toothpick utilization. However, when he returned to the hospital 2 days later, clinical suspicion for DIC was much higher. This was due to development of multiple sources of bleeding with worsening bicytopenia, progressive elevation of coagulation factors, and high levels of fibrin degradation products. Using the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) scoring algorithm, he had a score of 7 at the time of admission, which supported a diagnosis of DIC. Primary considerations were malignancy versus treatment-related causes. There was low suspicion for other causes of DIC, such as sepsis due to lack of fever, leukocytosis, or localizing symptoms. There was no associated severe trauma or obstetrical emergency in this case.

Treatment

Despite discontinuation of his imatinib, he returned to the ED several times due to episodes of bleeding. He was hospitalized for DIC a second time 1 week following discharge with hematuria and gingival bleeding. Urology performed an inpatient cystoscopy to evaluate his painless gross hematuria without significant findings. He received many units of cryoprecipitate and packed red blood cells throughout the admission to replete for levels of hemoglobin greater than 7 g/dL and fibrinogen greater than 100. Given his progression of disease on imatinib, suspicion for GIST driving his DIC due to recurrent bleeding off medication, and lack of new mutations on repeat next generation sequencing, sunitinib 50 mg daily (28 out of 42 days) was started on discharge.

His third admission for DIC occurred about 2 weeks later with gingival bleeding and epistaxis. Sunitinib was discontinued on admission. He remained out of the hospital for the next month although with frequent outpatient laboratory checks and transfusions. He was also started on ripretinib 150 mg daily. He returned to the hospital with gingival bleeding and hematuria and was admitted for the fourth time with concern for DIC. A CT scan of his head on admission revealed a small intracranial hemorrhage in the right temporal lobe. CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis noted bilateral nonobstructive pulmonary emboli that appeared to be subacute to chronic, tumor thrombus in left renal vein, near occlusive inferior vena cava tumor thrombus, and disease progression of pulmonary metastases. Following improvement in bleeding and stability of intracranial hemorrhage on serial CT head scans, he was initiated on therapeutic enoxaparin at 60 mg twice daily. Ripretinib was held on admission and restarted on discharge.

After initiating enoxaparin, his coagulopathy improved. About 1 month later the enoxaparin was transitioned to apixaban 5 mg twice daily for patient preference. Four days later he presented to the ED with gingival bleeding and was admitted for DIC for the fifth time. His bleeding resolved, and he was discharged on enoxaparin 60 mg twice daily instead of apixaban. Ripretinib was held on admission and restarted on discharge. A few weeks later he was briefly hospitalized for abdominal pain. CT angiography abdomen and pelvis demonstrated progression of disease in the liver, left adrenal gland, peritoneum as well as new splenic vein tumor thrombus and left renal infarctions.

Follow-up and outcomes

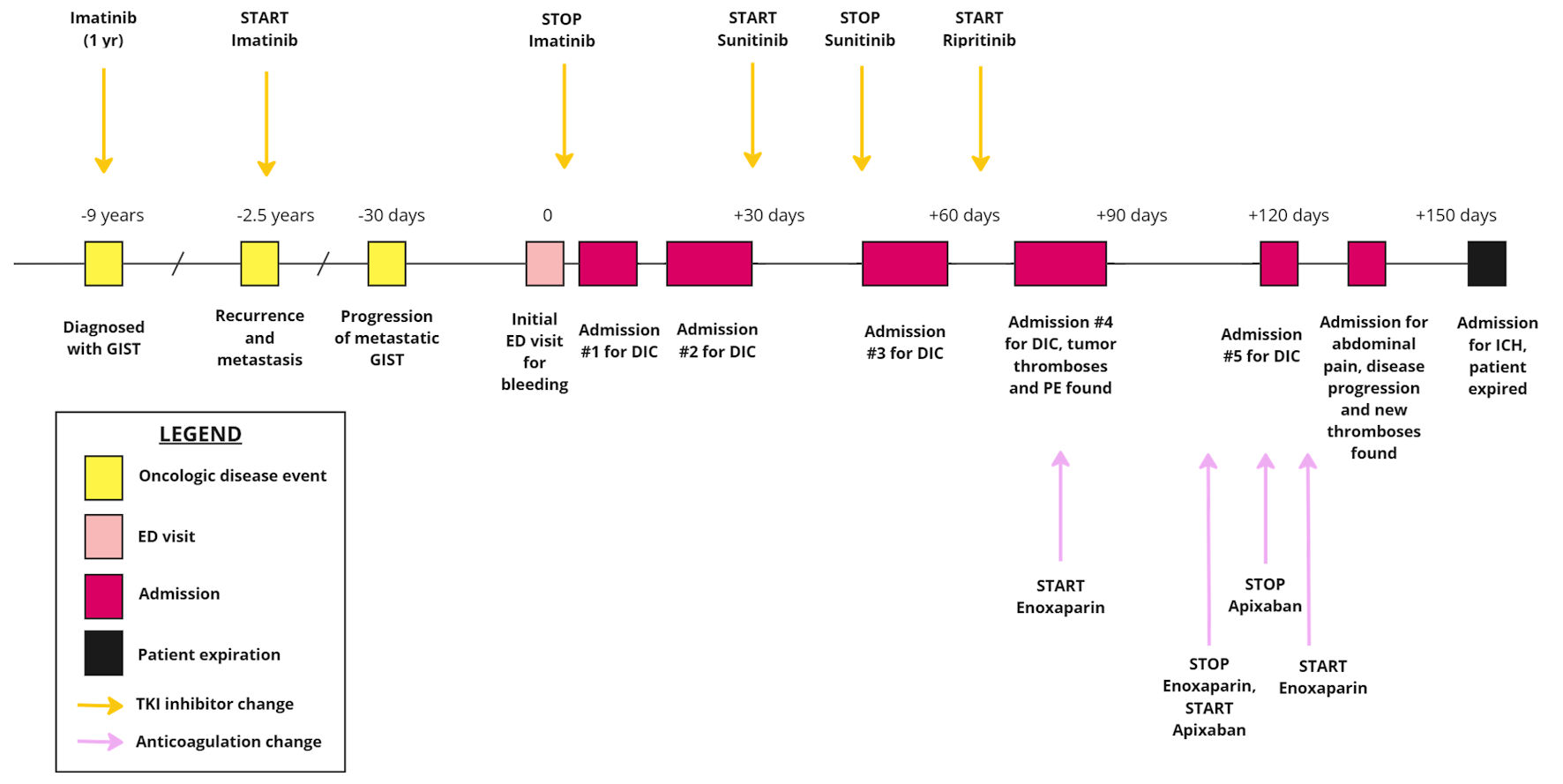

Around 5 - 6 months after the initial presentation for DIC (Fig. 3), the patient was found unresponsive at home. CT head demonstrated large left sided intraparenchymal hemorrhage and intraventricular hemorrhage with midline shift and uncal herniation. Neurosurgery was consulted though hemorrhage and herniation deemed too significant for surgical intervention, patient transitioned to comfort-focused care in the neurocritical care unit and passed away.

Click for large image | Figure 3. The timeline of patient’s oncologic disease and progression with subsequent presentations to the hospital, highlighting the initiation and cessation of TKI inhibitors as well as anticoagulant therapies. GIST: gastrointestinal stromal tumor; DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation; ED: emergency department; TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitor. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

DIC is a severe, life-threatening condition with numerous underlying causes, though can be observed in advanced malignancy. DIC can be acute or chronic. This patient’s mild laboratory derangements and prolonged clinical course were consistent with a chronic phenotype. The chronic nature of DIC in this case presentation provides insight into the complexity of disease progression, coagulopathy, and treatment modalities in metastatic GIST.

The pathophysiology of DIC depends on the underlying disease state but involves the simultaneous initiation of coagulation, impairment of anticoagulation, fibrinolysis, and dysregulation of fibrin removal [1]. Cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6, play an important role in the response system. Tumor cells may express procoagulant factors, such as tissue factor, which activate the coagulation cascade [7]. Tissue factor interacts with factor VII in the extrinsic pathway of hemostasis, resulting in thrombin formation. Cytokines further disrupt the protein C system, impairing the natural anticoagulant process [1]. In DIC, compared to other coagulopathies, all anticoagulant pathways are impaired. Furthermore, in malignancy, these simultaneous processes often result in venous thromboembolism, though severe thrombocytopenia and factor deficiencies can contribute to bleeding as well [7, 8].

DIC is classically associated with particular malignancies, such as metastatic adenocarcinoma and lymphoproliferative disease, but is not known to be associated with metastatic GIST. Acute DIC in malignant GIST, while rare, is a more established complication than chronic or recurrent DIC [9]. To our knowledge, only one case report from 2001 described recurrent or chronic DIC in GIST. It reported a case of a male in his 60s, whose DIC was the first and predominant symptom of his disease, which was only pathologically confirmed on autopsy [10]. In our case, the initial presentation with bleeding occurred about 1 month following disease progression on CT imaging. Interestingly, this occurred shortly after having an adrenal biopsy. For the first few months of his chronic DIC, he had bleeding-predominant DIC. As his disease continued to progress, new thromboses and pulmonary emboli were found, and he developed mixed bleeding and thrombotic DIC. In the setting of solid malignancies, DIC typically occurs in advanced or metastatic disease [11, 12]. Notably, his underlying KIT mutation, specifically the deletion of Trp557_Lys558 on exon 11, is associated with increased risk of metastatic disease [6, 13]. The presentation and persistence of his DIC, coinciding with progression of disease on imaging, suggests that his advanced disease may have been the primary cause of his chronic consumptive coagulopathy.

Additionally, the patient’s treatment history provides insight into how cancer therapies may influence coagulopathy. He was initially treated with imatinib as adjunctive therapy and later continued for metastatic disease and disease progression. Imatinib is known to cause myelosuppression with thrombocytopenia, and there are additional reports of drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia [14]. Despite transitioning to other TKI inhibitors, including sunitinib and ripretinib, he continued to have episodes of DIC (Fig. 3). Sunitinib can cause myelosuppression, thrombocytopenia, and bleeding as well, with a few case reports of DIC occurring during sunitinib therapy [15, 16]. Hematologic adverse events seem to be less common with ripretinib than other TKI inhibitors [17]. The persistence of DIC while discontinuing and changing TKI inhibitors suggests that the primary underlying etiology may not have been medication-induced.

The diagnosis and management of DIC have historically been a challenge with few clear guidelines. This led to the creation of a scoring system to aid in the diagnosis of DIC by the ISTH [18]. The scoring algorithm takes into consideration platelet count, levels of fibrin markers, PT, and fibrinogen level, with a score of 5 or greater being compatible with DIC. In this case, DIC was the top working diagnosis early in the clinical course given bleeding, coagulopathy, and elevated fibrin breakdown products. The ISTH score was 5 or greater for all of his admissions for bleeding, excluding his final admission with intracranial bleeding, as no D-dimer laboratory test was sent, thus the score unable to be calculated. The scoring algorithm combined with his clinical presentations supports the diagnosis of DIC for each of his admissions. However, the trigger of DIC was difficult to identify, which made management challenging.

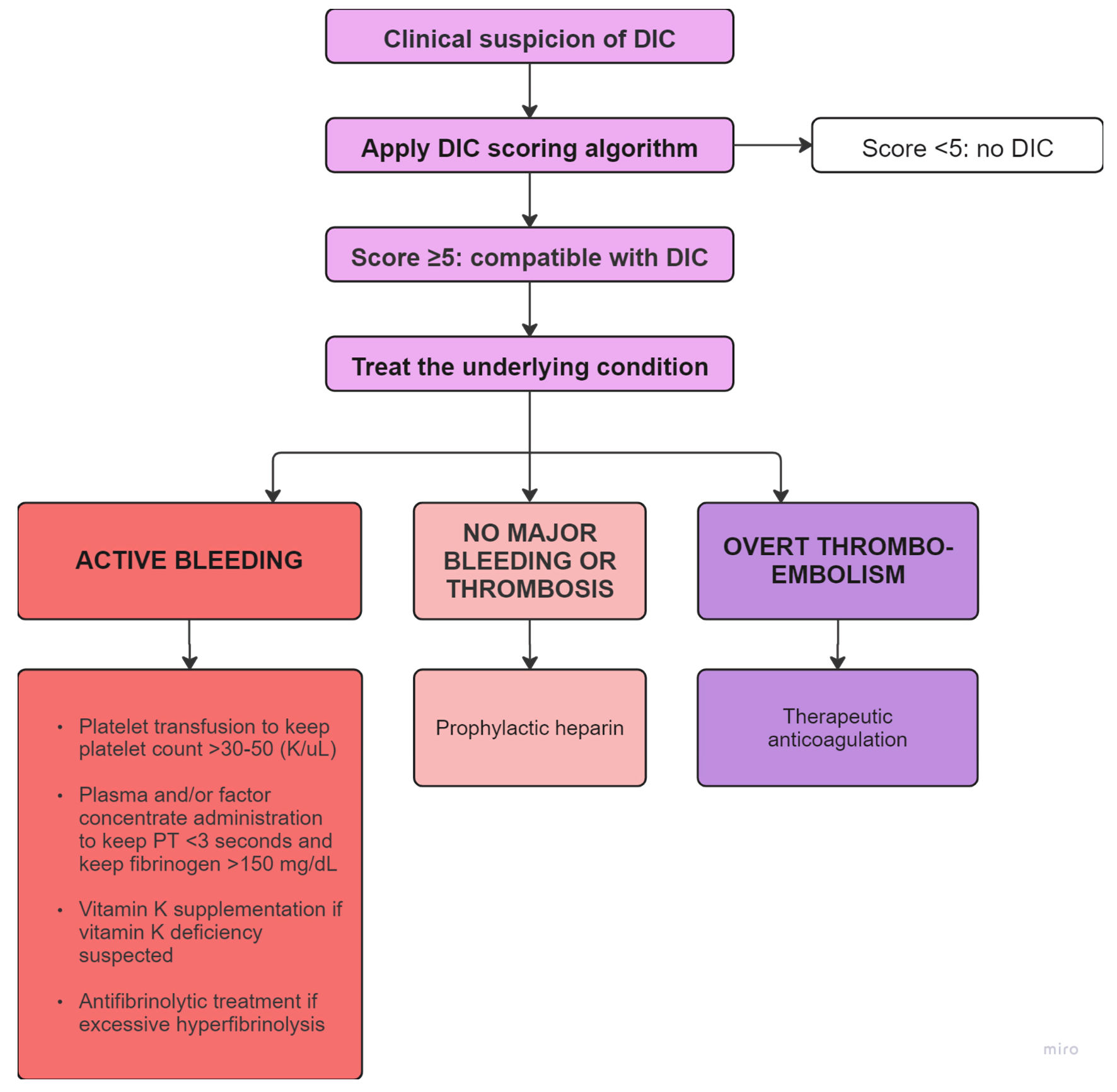

While clinical suspicion and laboratory data can lead to the diagnosis of DIC, the challenge often involves identifying and treating the underlying condition, as well as determining whether the DIC is predominantly bleeding or thromboembolic (Fig. 4) [1, 18]. In cases of active bleeding, treatment is supported by transfusions and product replacement. In cases of thromboembolism, treatment is supported with therapeutic anticoagulation [1]. An additional point of interest in this case is that the patient had variable responses to anticoagulants. He was initially treated with enoxaparin when he developed thromboembolism in addition to bleeding. However, when enoxaparin was transitioned to apixaban, he re-presented to the hospital a couple days later with worsening bleeding symptoms (Fig. 3). There are limited data on the selection of anticoagulants and the use of direct oral anticoagulants in DIC, with only case reports available and no clinical trials found on our search [19, 20]. No guidelines exist for anticoagulant selection and adjustment in DIC in the setting of malignancy.

Click for large image | Figure 4. Flowchart depicting the diagnosis and management of DIC based on bleeding or thromboembolic predominance [1, 18]. This flowchart was adapted from flowchart developed by Levi et al [1]. PT: prothrombin time; DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation. |

In summary, this case represents a rare occurrence of chronic DIC in metastatic GIST as only the second known report of chronic DIC in a patient with GIST. Despite adjustments in his cancer therapies and anticoagulation he continued to have episodes of DIC with frequent hospitalizations and ultimately death. Further research is warranted on the selection of and potential variability in bleeding risks of different anticoagulants in DIC. The complexity of tumor-induced coagulopathy and impact of cancer therapies on coagulation highlights the need for additional research into tailored management to improve outcomes in similar cases.

Learning points

This case highlights several key learning points. Firstly, DIC in either the acute or chronic form may suggest disease progression in advanced malignant GIST and should prompt further assessment, including imaging. Secondly, while TKI inhibitors can manage DIC by treating the underlying disorder if thought to be malignancy-related, they should be considered as an alternative cause of DIC or similar hematologic abnormality. And thirdly, anticoagulation is a critical component of the management of DIC with thromboembolism; however, there is limited understanding on optimal anticoagulant therapy selection and adjustment.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

The patient passed away prior to the case report being written. Verbal and written consent was obtained from the patient’s daughter.

Author Contributions

All authors were actively involved in writing and revising the article. Emily Bopp was involved in substantial contributions to conception of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; drafting and revising for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Zhu Cui was involved in substantial contributions to conception and design of the work; drafting and revising for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Jacob Elkon was involved in substantial contributions to conception and design of the work; the analysis and interpretation of the data; drafting and revising for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this case report are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Levi M, Scully M. How I treat disseminated intravascular coagulation. Blood. 2018;131(8):845-854.

doi pubmed - Levi M, van der Poll T. Coagulation and sepsis. Thromb Res. 2017;149:38-44.

doi pubmed - Wada H, Matsumoto T, Yamashita Y. Diagnosis and treatment of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) according to four DIC guidelines. J Intensive Care. 2014;2(1):15.

doi pubmed - Zhao X, Yue C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3(3):189-208.

doi pubmed - Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Maki RG, Pisters PW, Demetri GD, Blackstein ME, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097-1104.

doi pubmed - Kontogianni-Katsarou K, Dimitriadis E, Lariou C, Kairi-Vassilatou E, Pandis N, Kondi-Paphiti A. KIT exon 11 codon 557/558 deletion/insertion mutations define a subset of gastrointestinal stromal tumors with malignant potential. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(12):1891-1897.

doi pubmed - Falanga A, Marchetti M, Vignoli A. Coagulation and cancer: biological and clinical aspects. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(2):223-233.

doi pubmed - Feinstein DI. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in patients with solid tumors. Oncology (Williston Park). 2015;29(2):96-102.

pubmed - Nishimura M, Komori A, Matsushita M, Fukutani A, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the small intestine: rare complication of acute disseminated intravascular coagulation without hematogenous metastasis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(10):2271-2277.

doi pubmed - Kajor M, Hrycek A, Kosmider J, Rys J, Smok M. [Recurrent disseminated intravascular coagulation in the course of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST)]. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2001;106(4):945-949.

pubmed - Vitale FV, Longo-Sorbello GS, Rotondo S, Ferrau F. Understanding and treating solid tumor-related disseminated intravascular coagulation in the "era" of targeted cancer therapies. SAGE Open Med. 2017;5:2050312117749133.

doi pubmed - Sallah S, Wan JY, Nguyen NP, Hanrahan LR, Sigounas G. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in solid tumors: clinical and pathologic study. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(3):828-833.

pubmed - Wardelmann E, Losen I, Hans V, Neidt I, Speidel N, Bierhoff E, Heinicke T, et al. Deletion of Trp-557 and Lys-558 in the juxtamembrane domain of the c-kit protooncogene is associated with metastatic behavior of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Int J Cancer. 2003;106(6):887-895.

doi pubmed - Radwi M, Cserti-Gazdewich C. Drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia associated with use of tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib. J Taibah University Medical Sciences 2015;10(3):365-368.

doi - Olivo A, Noel N, Besse B, Taburet AM, Lambotte O. Disseminated intravascular coagulation following administration of sunitinib. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;5(1):121-123.

doi pubmed - Tareen M, Zuluaga JO, El Khoury M, Salem S, Khan F. Sunitinib induced disseminated intravascular coagulation after COVID-19 infection in a patient with neuroendocrine tumor: a case report. New Emirates Medical Journal; 2024;5:e140723218725.

doi - Zalcberg JR. Ripretinib for the treatment of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211008177.

doi pubmed - Taylor FB, Jr., Toh CH, Hoots WK, Wada H, Levi M, Scientific Subcommittee on Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH). Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(5):1327-1330.

pubmed - Lippi G, Langer F, Favaloro EJ. Direct oral anticoagulants for disseminated intravascular coagulation: an alliterative wordplay or potentially valuable therapeutic interventions? Semin Thromb Hemost. 2020;46(4):457-464.

doi pubmed - Yamada S, Asakura H. Therapeutic strategies for disseminated intravascular coagulation associated with aortic aneurysm. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1296.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.