| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 9, September 2025, pages 345-351

Renal Cell Carcinoma in A Girl With Tuberous Sclerosis Due to a New Mutation

Ibrahim Alharbia, Ascia K. Alabbasib, c, Fay K. Salawatib, Razan A. Alghamdib

aDepartment of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Umm Al-Qura University, Mecca, Saudi Arabia

bCollege of Medicine, Umm Al-Qura University, Mecca, Saudi Arabia

cCorresponding Author: Ascia K. Alabbasi, College of Medicine, Umm Al-Qura University, Mecca, Saudi Arabia

Manuscript submitted June 1, 2025, accepted August 25, 2025, published online September 17, 2025

Short title: A Girl With TS Due to a New Mutation

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5147

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a neurocutaneous disorder inherited in autosomal dominant manner. It is characterized by multisystem involvement due to the formation of hamartomas in different organs. TSC2 gene mutations are the most common cause of the disease and are associated with more severe neurological symptoms compared to TSC1 gene mutations. However, in our case, we are reporting a rare mutation detected at the flanking splice site of exon 37 in the TSC2 gene in a 2-year-5-month-old girl. She presented to the emergency department at the age of 1 month with generalized abnormal body movements. A review of genetic databases revealed no prior reports of this gene in the literature. Her diagnosis was confirmed by gene panel for TCS. Later, she developed renal cell carcinoma. Such cases are managed by a multidisciplinary team including a pediatrician, a pediatric neurologist, a pediatric cardiologist, a pediatric hematology-oncology specialist, and specialist in pediatric surgery. The overall prognosis of children with TSC is variable and dependent on the severity of symptoms, especially neurologic manifestations.

Keywords: Tuberous sclerosis; Rare mutation; Pediatric; Renal cell carcinoma

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a rare genetic disease involving multiple systems. It is caused by mutations of TSC1 or TSC2 genes with consequent dysregulation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) [1, 2]. TSC is a part of a group of conditions known as neurocutaneous syndromes. TSC is characterized by hamartomas that develop in multiple organ systems including the brain, skin, kidney, heart and lungs [3, 4]. Among the key contributors to morbidity are neurological manifestations, including epilepsy and cognitive impairments, hence the need for early diagnosis and interventions to improve quality of life [5]. Management of this syndrome usually involves a multidisciplinary approach, and in TSC, mTOR inhibitors have become one of the most promising treatment modalities [6, 7].

The prevalence of TSC is estimated to be approximately 1 in 6,000 to 10,000 individuals in the general population. Yet, no particular prevalence studies concerning TSC in Saudi Arabia exist. Individuals of any race and ethnicity can be affected by TSC. It occurs at equal frequency among males and females [8]. The common clinical manifestations are episodes of epilepsy, skin lesions and developmental delay, with epilepsy showing the highest incidence, reported in 65.9-86.9% of patients [8, 9]. These manifestations of TSC vary depending on the specific organ system affected. In children, early manifestations typically include seizures, intellectual disabilities, and hypopigmented macules, whereas adults are more likely to present with renal angiomyolipomas or pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis [10, 11].

TSC, like some other neurocutaneous conditions (such as neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)), possesses features that help guide clinicians toward an accurate diagnosis [12, 13]. Both diseases show autosomal dominant inheritance with a very high rate of spontaneous mutations and thus require genetic counseling and multidisciplinary care [14, 15]. Sporadic cases of TSC occur in about 60-70% of TSC cases, through de novo mutations [16, 17]. Mutations in TSC2 are more prevalent and correlate with a more severe phenotype than those in TSC1 [18, 19].

After reviewing gene databases, we can say this is the first reported case in which a novel heterozygous mutation has been identified at the flanking splice site of exon 37 in the TSC2 gene. We found this mutation in a child diagnosed with TSC. Such mutations are infrequent internationally and had not previously been reported in the region. This finding highlights the relevance of genetic testing for diagnostic confirmation of TSC, particularly among populations with minimal genetic information available. Identification of new mutations has important implications for mechanistic understanding of disease, diagnosis precision and therapeutic interventions [20, 21]. It is expected that advanced genetic techniques such as next-generation sequencing will continue to improve the mutations detection rates, allowing for better early diagnosis and individualized management plans for children with TSC.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 2-year-5-month-old female came to the emergency department with a 5-day history of generalized abnormal body movements and up-rolling of both eyes. The frequency of attacks was five to six times per day. Each attack lasted for approximately 10 s. The attacks were associated with decreased feeding and activity with no history of fever. She experienced her first episode of seizure at the age of 1 month, and she was on phenobarbital as anti-epileptic medication. The patient has a positive family history of tuberous sclerosis (TS) from her mother side. Upon physical examination, multiple hypopigmented patches (ash leaf) over her right leg, chest, abdomen, and left arm were noted. There were no other significant findings.

In terms of her investigations, a hematological workup was done, and test results indicated hemoglobin of 141g/L, hematocrit of 40%, and low mean platelet volume (MPV) of 7.3 fL. She also had leukocytosis with lymphocyte predominance. Electroencephalography (EEG) showed active discharges with polyspike waves on a suppression background along with bilateral sharp waves. There were no abnormalities detected on the echocardiogram.

A gene panel for TS was conducted and revealed a heterozygous mutation in the flanking splice site of exon 37 of TSC2, (RefSeq: GRCh37 (hg19)). According to the result, the diagnosis was confirmed to be TS.

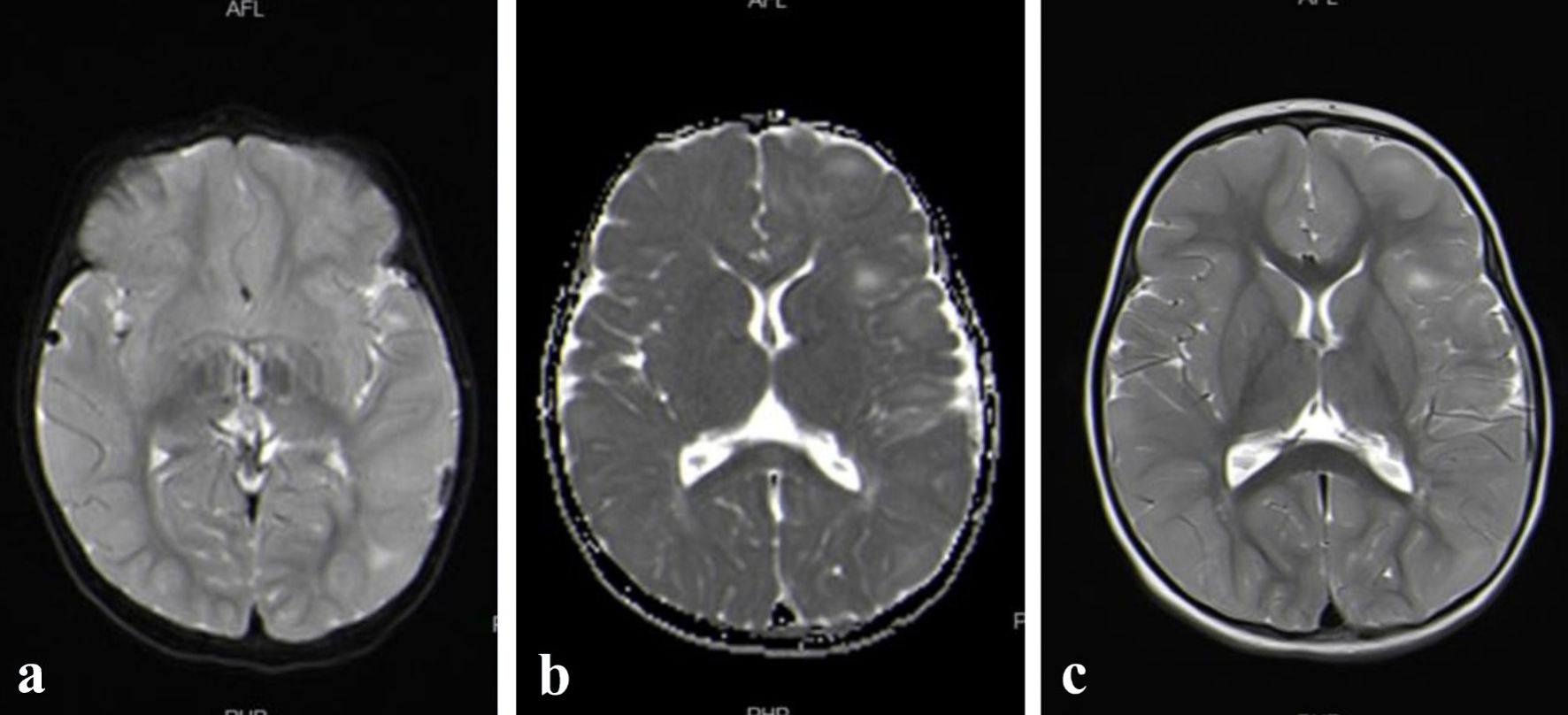

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reported multiple subependymal nodules, with a mild subtle increase in the enhancement of the lesion on the left centrum semiovale (Fig. 1a-c).

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a, b, c) Brain MRI reported multiple subependymal nodules, with a mild subtle increase in the enhancement of the lesion on the left centrum semiovale. MRI: magnetic resonance imaging. |

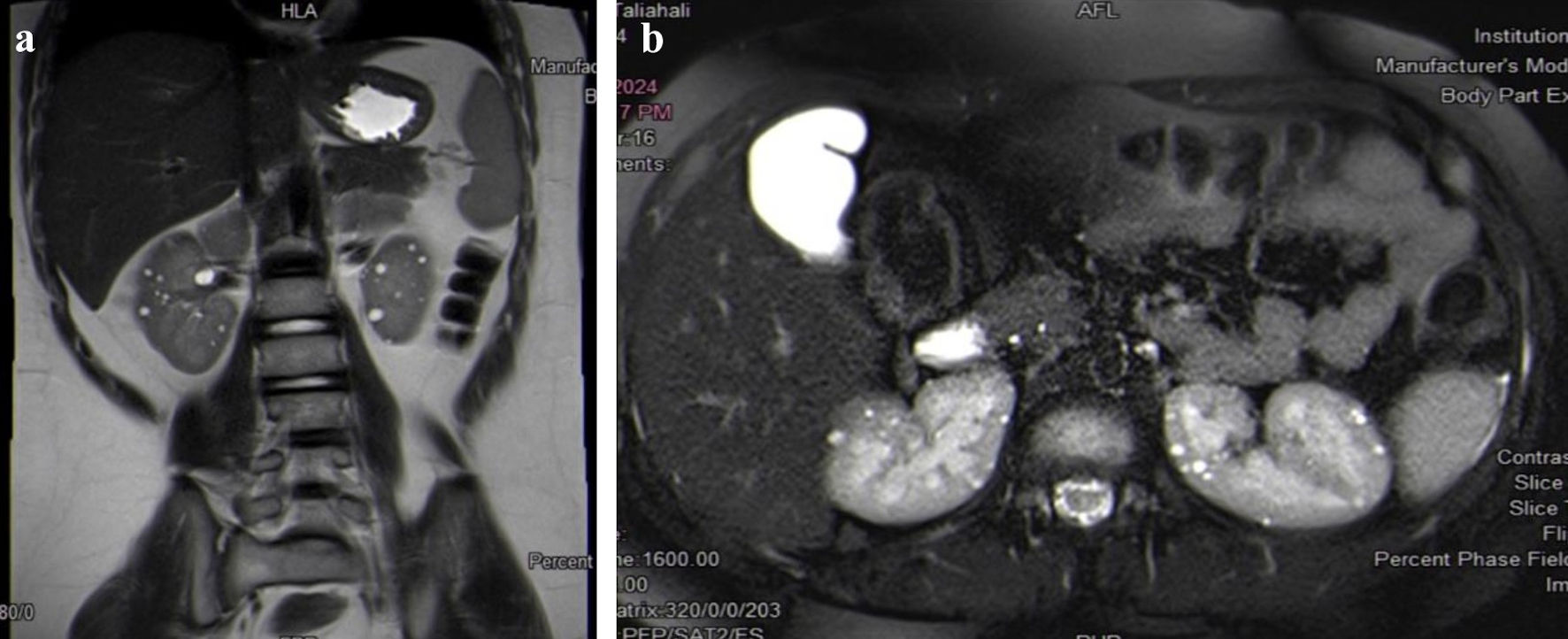

Kidney MRI showed multiple innumerable renal cysts, the largest measured 0.8 cm. There is a well-defined round cortical lesion that is noted at the interpolar region of the right kidney. It appears as isointense in comparison to the renal cortex at T1- and T2-weighted images. Radiology suggested that the described right interpolar lesion is worrisome for renal cell carcinoma. Other possibilities of the nature of this lesion may include lipid-poor angiomyolipoma or oncocytoma (Fig. 2a, b).

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a, b) Kidney MRI shows multiple innumerable renal cysts, the largest measuring 0.8 cm. A well-defined round cortical lesion is noted in the interpolar region of the right kidney, which is concerning for renal cell carcinoma. MRI: magnetic resonance imaging. |

Computed tomography (CT) chest scan with intravenous (IV) contrast revealed a small irregular area of ground-glass density within the left lower lobe. As well, the visualized part of the upper abdomen demonstrated a partial clear view of a hypodense right renal lesion.

The patient was referred to oncology due to suspicion of renal cell carcinoma. The tumor board discussed her condition, and a partial nephrectomy was decided. She underwent wedge resection of the right kidney on January 6, 2025. The histopathological examination of the biopsied specimen reported a grade II renal cell carcinoma. There are no sarcomatoid, rhabdoid features, nor tumor necrosis, and no lymphatic or vascular invasion. On gross examination, the specimen consisted of multiple fragments of brown-tan renal tissue (4 × 2.1 × 1.3 cm) aggregates and a separate white-tan nodule (1.7 × 1.5 × 1.3 cm). Sectioning of the renal tissue reveals homogenous brown-tan cut surface with foci of hemorrhage. Sectioning of the nodule reveals a homogenous white-tan cut surface.

The oncology team met and discussed the case. Since the tumor resection margins were negative and there was no metastasis, and based on the most recent evidence, it was decided that no chemotherapy was needed. However, further management included follow-up with ultrasound every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for 3 years.

The patient has a history of recurrent emergency room (ER) visits with fevers, upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) symptoms, and seizure attacks, especially when non-compliance to anti-convulsant medications. She is now regularly following up with neurology, ophthalmology, and nephrology. She is on topiramate and valproate as anti-convulsant medications.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

TS is a rare genetic disease inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern that affects multiple organs in the body. TSC results from mutations in the TSC1 or TSC2 genes. These mutations lead to the overactivation of the rapamycin pathway, which regulates cellular growth and proliferation [22, 23].

The incidence of the disease is estimated to be approximately 1 in 6,000 to 10,000 in the general population, with no sex or ethnicity predominance. About two-thirds of the cases are sporadic and show no family history [8]. TSC2 gene mutations are more common than TSC1 mutations. Studies show that individuals with TSC2 mutations experience more severe symptoms than those with TSC1. Additionally, patients with TSC2 mutations are more susceptible to neuropsychiatric features, including autism, intellectual impairment, and lower intelligence quotients [8, 24]. This study presents a case of TS with TSC2 gene mutation.

While most cases are observed with no family history, this case presents with a positive family history. A 2011 Boston cohort study of 278 patients found that TSC1 mutations were more often linked to a family history of TSC or hypopigmented macules than TSC2 mutations [25]. Contrary to our study, the case we present involves a patient with a TSC2 mutation who also has a positive family history and exhibits hypopigmented macules.

TS can affect multiple organs, including brain, skin, heart, kidneys, and lungs. The clinical manifestations are categorized into neurological and non-neurological features. Neurological impairment is the primary source of mortality and morbidity [24]. Neurological features in TSC include epilepsy, cortical tubers, subependymal nodules, giant cell astrocytoma, intellectual disabilities, and autism. Non-neurological features can be cutaneous skin lesions such as facial angiofibroma or shagreen patches. Additional characteristics include renal angiomyolipoma, intracardiac rhabdomyoma, and retinal astrocytic hamartomas [22]. The most common manifestations of TSC include cutaneous skin lesions in more than 95% of cases, seizures in approximately 85%, and intellectual disability in about 50% of cases [26]. Our case began exhibiting symptoms at 1 month of age, presenting with a generalized seizure. Examination revealed multiple hypopigmented patches, known as ash leaf spots, on her right leg, trunk, and left arm. Further investigations showed active discharges with polyspike waves on a suppression background and bilateral sharp waves on EEG. Brain MRI reported multiple subependymal nodules. Kidney MRI revealed several renal cysts that were diagnosed as renal carcinoma upon histopathological examination.

Diagnosis of TSC can be challenging. There are no single or specific pathognomonic characteristics found in all patients [25]. According to a Saudi study, the mean age at diagnosis was 4.9 years. In contrast, Staley et al noticed that the mean age at diagnosis was 7.5 years. [8, 25]. The second International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Conference reviewed the diagnostic criteria of TSC to implement updates from the previous criteria established in 1998. The most notable change is the inclusion of genetic testing, which facilitates the ability to confirm a TSC diagnosis. Identifying a TSC1 or TSC2 genetic mutation is sufficient to establish the diagnosis. Although genetic testing may not be accessible in resource-limited countries, clinical criteria remain the primary method to make the diagnosis [27]. The clinical criteria are categorized into major and minor features (Table 1). The diagnosis is made when two major criteria are present, or one major criterion and two minor criteria are met [28]. To confirm the diagnosis in our presented case, a genetic analysis was performed. The gene panel identified a heterozygous mutation in the flanking splice site of exon 37 of TSC2 (RefSeq: GRCh37 (hg19)). We think this is a new de novo mutation that has never been reported in the literature before.

Click to view | Table 1. The Clinical Criteria for the Diagnosis of Tuberous Sclerosis |

Treatment for TS requires a multidisciplinary approach with regular follow-up [29]. Management primarily focuses on treating epilepsy by anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs). Non-pharmacological treatment like surgical interventions, ketogenic diet, and vagus nerve stimulation can also be considered. However, approximately one-third of patients develop resistance to therapy. According to the International TSC Consensus Guidelines, vigabatrin is the first-line treatment for TSC-associated epilepsy [29, 30]. For patients with therapy-resistant epilepsy, mTOR inhibitors can be used and may also help reduce other TSC-related lesions, such as renal angiomyolipomas and facial angiofibromas [29]. Given the limited response to AEDs, patients may benefit from non-pharmacological therapies. The ketogenic diet is the most commonly used effective non-pharmacological treatment, although its mechanism remains unclear. Additionally, data suggest that neurostimulation may be beneficial for certain adults. [31] Surgery and selective arterial embolization can also be considered for TSC-related lesions. [29].

We are reviewing 12 cases of TSC, ranging in age from 1 month old to 31-year (Table 2, [23, 32-37]). The patients presented with different clinical features of TSC, with the most common being seizure in early childhood. Sarjan et al reported a case of a 17-month-old girl, who arrived at a tertiary care center with complaints of unusual body movements, characterized by stiffening of her left arm, upward eye rolling, and frothing at the mouth [32]. Similarly, Alshoabi et al [33] reported a case of a 19-year-old male at University Medical Center, who suffered from recurrent, intractable seizures, experiencing three to seven episodes daily since he was 6 months old. Also, they noted a 2.5-year-old girl who had been having seizures since she was 3 months old. Now she presented with a marked increase in frequency and severity, experiencing five to 12 seizures per day [33]. Helmy et al reported two sibling cases, including a 3-month-old girl with tonic-clonic seizures and delayed speech, cognition, and social development. The other sibling was a 6-year-old boy, who also developed convulsions at the age of 4 months, controlled on anti-epileptic medications. [23]. These cases share similarities with our own, as all initial symptoms involved seizure attacks occurring at a young age in early childhood.

Click to view | Table 2. Summary of 12 Cases of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) |

Seizure is not always the first presenting complaint in some patients. Aboud et al reported a unique presentation of a 32-year-old patient with multiple unilateral asymptomatic skin-colored papules on the back of the neck, associated with a hypopigmented patch with no other features [34]. A similar case was reported by Supekar et al [35] involving a 24-year-old male who presented with lesions that first appeared at 9 years of age and progressively increased in number and size. There was no history of seizures, headache, visual or auditory disturbances, or mental retardation [35]. Another case was reported by Zhang et al about a 31-year-old woman who presented with erythema and nodules in the face, neck, and oral cavity, which had appeared shortly after she was born. She found several grain-sized hypopigmentation spots on her back too. The patient had no history of epilepsy or intellectual disability [36]. Case series was reported by Chatterjee et al about three females and one male ranging in age between 11 months to 7 years. All four cases presentations included multiple cutaneous manifestations such as hypomelanotic macules and patches in the face, limbs, and trunk [37]. Similarly, our case also exhibited cutaneous features that were found upon examination. There were hypopigmented patches on her right leg, chest, abdomen, and left arm.

Conclusions

Herein, the first case of a new heterozygous mutation located at the flanking splice site of exon 37 of the TSC2 gene in a child with TSC is described. This finding confirms the importance of genetic testing in the diagnosis of TSC, especially in underrepresented populations. Detection of rare mutations improves understanding of the molecular mechanisms of the disease. This report further underlines the need for public and institutional awareness for early screening, along with the potential that early management may improve the outcome of the disease.

Learning points

This study highlights several important aspects of the clinical presentation and diagnosis of TSC. It describes a de novo mutation in the TSC2 gene that has not been previously reported in the literature, underscoring the importance of genetic testing in confirming the diagnosis. Moreover, the co-occurrence of renal cell carcinoma at a young age is particularly rare, as renal manifestations are more commonly seen in adults rather than in the pediatric population. Lastly, this study reinforces that early recognition of cutaneous signs can facilitate prompt diagnosis, thereby enabling earlier intervention and potentially improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

No funds were received for this research. The research was conducted with the utmost integrity and transparency, and the authors have no affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity that could pose a conflict of interest.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest that could potentially influence the study’s results or interpretation. This includes financial, personal, or professional relationships that could be perceived as having biased the work.

Informed Consent

Written consent has been obtained from the child’s parents.

Author Contributions

All listed authors certify that they have made substantial contributions to this manuscript. Each author has reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to submit it for publication. Ibrahim Alharbi, MD, principal author: supervision and critical review. Ascia K. Alabbasi (medical intern): manuscript writing and literature review. Fay K. Salawati (medical intern): manuscript writing. Razan A. Alghamdi (medical intern): manuscript writing.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Morrison PJ. Tuberous sclerosis: epidemiology, genetics and progress towards treatment. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;33(4):342-343.

doi pubmed - Crino P, Tsai. Tuberous sclerosis complex: genetic basis and management strategies. Adv Genomics Genet. 2012;19.

- Randle SC. Tuberous sclerosis complex: a review. Pediatr Ann. 2017;46(4):e166-e171.

doi pubmed - Krishnan A, Kaza RK, Vummidi DR. Cross-sectional imaging review of tuberous sclerosis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2016;54(3):423-440.

doi pubmed - Bonilla NC, Rodriguez Ceja AA, Garcia Santiago G, Gonzalez GA, Castro AA, Suarez JL. The tuberous sclerosis complex: a review of the literature. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2024;11(5):616-624.

- Habib SL, Al-Obaidi NY, Nowacki M, Pietkun K, Zegarska B, Kloskowski T, et al. Is mTOR inhibitor good enough for treatment all tumors in TSC patients? J Cancer. 2016;7(12):1621-1631

- Inoki K, Guan KL. Tuberous sclerosis complex, implication from a rare genetic disease to common cancer treatment. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(R1):R94-100.

doi pubmed - Almuqbil M, Aldoohan W, Alhinti S, Almahmoud N, Abdulmajeed I, Alkhodair R, Kashgari A, et al. Review of the spectrum of tuberous sclerosis complex: the Saudi Arabian experience. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2024;29(2):113-121.

doi pubmed - Almobarak S, Almuhaizea M, Abukhaled M, Alyamani S, Dabbagh O, Chedrawi A, Khan S, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: clinical spectrum and epilepsy: a retrospective chart review study. Transl Neurosci. 2018;9:154-160.

doi pubmed - Frost M, Hulbert J. Clinical management of tuberous sclerosis complex over the lifetime of a patient. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2015;6:139-146.

doi pubmed - Kingswood C, Bolton P, Crawford P, Harland C, Johnson SR, Sampson JR, Shepherd C, et al. The clinical profile of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) in the United Kingdom: A retrospective cohort study in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016;20(2):296-308.

doi pubmed - Torpy JM, Burke AE, Glass RM. JAMA patient page. Neurofibromatosis. JAMA. 2009;302(19):2170.

doi pubmed - Tolliver S, Smith ZI, Silverberg N. The genetics and diagnosis of pediatric neurocutaneous disorders: Neurofibromatosis and tuberous sclerosis complex. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40(4):374-382.

doi pubmed - Ferner RE. The neurofibromatoses. Pract Neurol. 2010;10(2):82-93.

doi pubmed - Kandt RS. Tuberous sclerosis complex and neurofibromatosis type 1: the two most common neurocutaneous diseases. Neurol Clin. 2002;20(4):941-964.

doi pubmed - Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex: genetic aspects. J Dermatol. 1992;19(11):914-919.

doi pubmed - Kwiatkowski DJ, Short MP. Tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(3):348-354.

pubmed - Jones AC, Daniells CE, Snell RG, Tachataki M, Idziaszczyk SA, Krawczak M, Sampson JR, et al. Molecular genetic and phenotypic analysis reveals differences between TSC1 and TSC2 associated familial and sporadic tuberous sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(12):2155-2161.

doi pubmed - Beauchamp RL, Banwell A, McNamara P, Jacobsen M, Higgins E, Northrup H, Short P, et al. Exon scanning of the entire TSC2 gene for germline mutations in 40 unrelated patients with tuberous sclerosis. Hum Mutat. 1998;12(6):408-416.

doi pubmed - Rosset C, Netto CBO, Ashton-Prolla P. TSC1 and TSC2 gene mutations and their implications for treatment in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: a review. Genet Mol Biol. 2017;40(1):69-79.

doi pubmed - Abdelwahed M, Touraine R, Ben-Rhouma B, Dhieb D, Mars M, Kammoun K, Hachicha J, et al. A novel de novo splicing mutation c.1444-2A>T in the TSC2 gene causes exon skipping and premature termination in a patient with tuberous sclerosis syndrome. IUBMB Life. 2019;71(12):1937-1945.

doi pubmed - Curatolo P, Moavero R, de Vries PJ. Neurological and neuropsychiatric aspects of tuberous sclerosis complex. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(7):733-745.

doi pubmed - Farihan Farouk Helmy, Adnan Amin Alsulaimani AAH, Alheraiti SS. Siblings with autism, mental retardation, and convulsions in tuberous sclerosis: a case report. World J Neurosci J [Internet]. 2016;6:220-226.

doi - Uysal SP, Sahin M. Tuberous sclerosis: a review of the past, present, and future. Turk J Med Sci. 2020;50(SI-2):1665-1676.

doi pubmed - Staley BA, Vail EA, Thiele EA. Tuberous sclerosis complex: diagnostic challenges, presenting symptoms, and commonly missed signs. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):e117-125.

doi pubmed - Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58(2):159.

doi pubmed - Karine L, Portocarrero L. Continuing medical education tuberous sclerosis complex: review based on new diagnostic criteria. an bras dermatalogia [Internet]. 2018;93(3):323-331.

doi - Li Y, Si Z, Zhao W, Xie C, Zhang X, Liu J, Liu J, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: a case report and literature review. Ital J Pediatr. 2023;49(1):116.

doi pubmed - Conte E, Boccanegra B, Dinoi G, Pusch M, De Luca A, Liantonio A, Imbrici P. Therapeutic approaches to tuberous sclerosis complex: from available therapies to promising drug targets. Biomolecules. 2024;14(9).

doi pubmed - Curatolo P, Jozwiak S, Nabbout R, SEGA TSCCMf, Epilepsy M. Management of epilepsy associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC): clinical recommendations. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2012;16(6):582-586.

doi pubmed - Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, Bissler J, Darling TN, de Vries PJ, Frost MD, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021;123:50-66.

doi pubmed - K CS, Bohaju A, Manandhar SR, Shrestha A, Aryal E, Maharjan P. Tuberous sclerosis complex in a 17-month-old: a case report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2023;61(262):562-565.

doi pubmed - Alshoabi SA, Hamid AM, Alhazmi FH, Qurashi AA, Abdulaal OM, Aloufi KM, Daqqaq TS. Diagnostic features of tuberous sclerosis complex: case report and literature review. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2022;12(1):846-861.

doi pubmed - Aboud AAL, Hakim M, Alheebi I, Alotaibi H, Bondogji YB, Alsaadi F, et al. Multiple unilateral angiofibromas with a hypopigmented patch as a possible presentation of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). Our Dermatology Online. 2024;15(3):265-267.

- Supekar BB, Wankhade VH, Agrawal S, Singh RP. Isolated unilateral facial angiofibroma or segmental tuberous sclerosis complex? Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12(2):327-329.

doi pubmed - Zhang X, Hu Y, Huang Y. An atypical cutaneous symptom in tuberous sclerosis complex: a case report and systematic review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2022;67(6):836.

doi pubmed - Chatterjee A, Sinha MK. Cutaneous and neurological profile of tuberous sclerosis complex in children: a case series and literature review. Panacea J Med Sci. 2022;12(1):215-220.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.