| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 8, August 2025, pages 287-292

An Unusual Entity in Urology: Urinary Bladder Paraganglioma

Ignacio Calleja Durana, b, Jose Emilio Hernandez Sancheza, Oana Beatrice Popescua

aDepartment of Urology, Hospital Universitario General de Villalba, Collado Villalba, Madrid, Spain

bCorresponding Author: Ignacio Calleja Duran, Department of Urology, Hospital Universitario General de Villalba, Collado Villalba, Madrid, Spain

Manuscript submitted May 26, 2025, accepted July 29, 2025, published online August 22, 2025

Short title: An Unusual Case of Urinary BPGL

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5145

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Bladder paraganglioma accounts for < 0.05% of all bladder tumors, and very few cases have been reported to date. Because clinical and radiological findings are often nonspecific, many lesions are misdiagnosed until surgery, exposing patients to preventable perioperative catecholamine crises. We report an unusual case of a 77-year-old woman, in whom a 17-mm bladder paraganglioma was discovered incidentally during imaging for suspected Crohn’s disease. The patient was entirely asymptomatic and had normal catecholamine levels. Transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB) achieved complete excision, and no recurrence was detected at 6-month follow-up. This case illustrates that bladder paraganglioma can occur outside the typical age range and without adrenergic symptoms, emphasizing the need to consider this entity in the differential diagnosis of any well-circumscribed, hypervascular bladder mass. Early recognition enables appropriate perioperative planning and long-term multidisciplinary surveillance. We discuss the tumor’s characteristics, management, and the importance of long-term surveillance.

Keywords: Bladder paraganglioma; Bladder tumor; Neuroendocrine tumor; Transurethral resection of the bladder; SDHB

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Bladder paraganglioma (BPGL) is a rare neuroendocrine tumor, with an estimated frequency of less than 0.05% of all bladder tumors and approximately 10% of extra-adrenal paragangliomas. It is more common in female than males and usually occurs at the age of 20 - 50 years, so our case represents a particularly late presentation [1].

When small, BPGLs are usually spherical, well-marginated and homogeneous, larger BPGLs are typically more complex, with peri- and intra-tumoral neovascularity and central necrosis [2].

These tumors originate from chromaffin cells of the sympathetic nervous system, primarily in the muscularis propria of the bladder wall, with a predilection for the trigone and bladder dome [1, 2].

Although most cases occur sporadically, BPGL can be associated with hereditary syndromes, including paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma (PGL/PCC) syndrome, von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2), and neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) [3, 4].

Clinical manifestations are related to catecholamine excess and/or mass effects [3-5]. Bursting headache, anxiety, pounding sensation, sweating, blurred vision are part of the characteristic symptom complex called “micturition attack” [3, 4]. Hypertension is observed in most patients [3, 4, 6].

We present this case because it underscores an atypical scenario: a 77-year-old woman with an incidentally discovered, biochemically silent bladder mass that proved to be a paraganglioma. Its novelty lies in three aspects. First, the patient’s age is well beyond the usual fourth-to-fifth-decade range described in most series - only a handful of cases over 70 years have been reported. Second, the tumor was entirely asymptomatic and non-secretory, reminding clinicians that functional inactivity does not exclude the diagnosis of paraganglioma. Third, the lesion, although extramural, measured only 17 mm and was successfully managed with en-bloc transurethral resection, illustrating that a conservative endoscopic approach can be curative when imaging shows a well-circumscribed tumor confined to the bladder wall. Together, these features reinforce the need to keep BPGL in the differential diagnosis of any bladder mass, even when patient demographics and clinical presentation are not typical for this rare entity.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 77-year-old woman with no history of smoking or exposure known bladder carcinogens was referred in June 2024 to our hospital after an incidental finding of a urinary bladder mass. It was first described in a computed tomography (CT) scan to study a possible Crohn’s disease flare. CT report described the mass as a 17-mm vesical nodule adjacent to right posterolateral wall suspicious of malignancy (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT of the bladder. The red arrow points at a 17-mm solid vesical nodule adjacent to the right posterolateral wall suspicious for malignancy. This was the incidental finding of the tumor. CT: computed tomography. |

The patient reported no hematuria or lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), and no other symptoms were noted. The patient has a history of nonspecific thoracic pain. A prior cardiac stress test showed no electrocardiogram (ECG) changes but was considered clinically positive due to hypertensive response. A coronary angiography revealed no significant epicardial coronary lesions. In 2020, she underwent a repeat evaluation for recurrent chest pressure; a stress echocardiogram was negative for ischemia, although again notable for a hypertensive blood pressure response.

Diagnosis

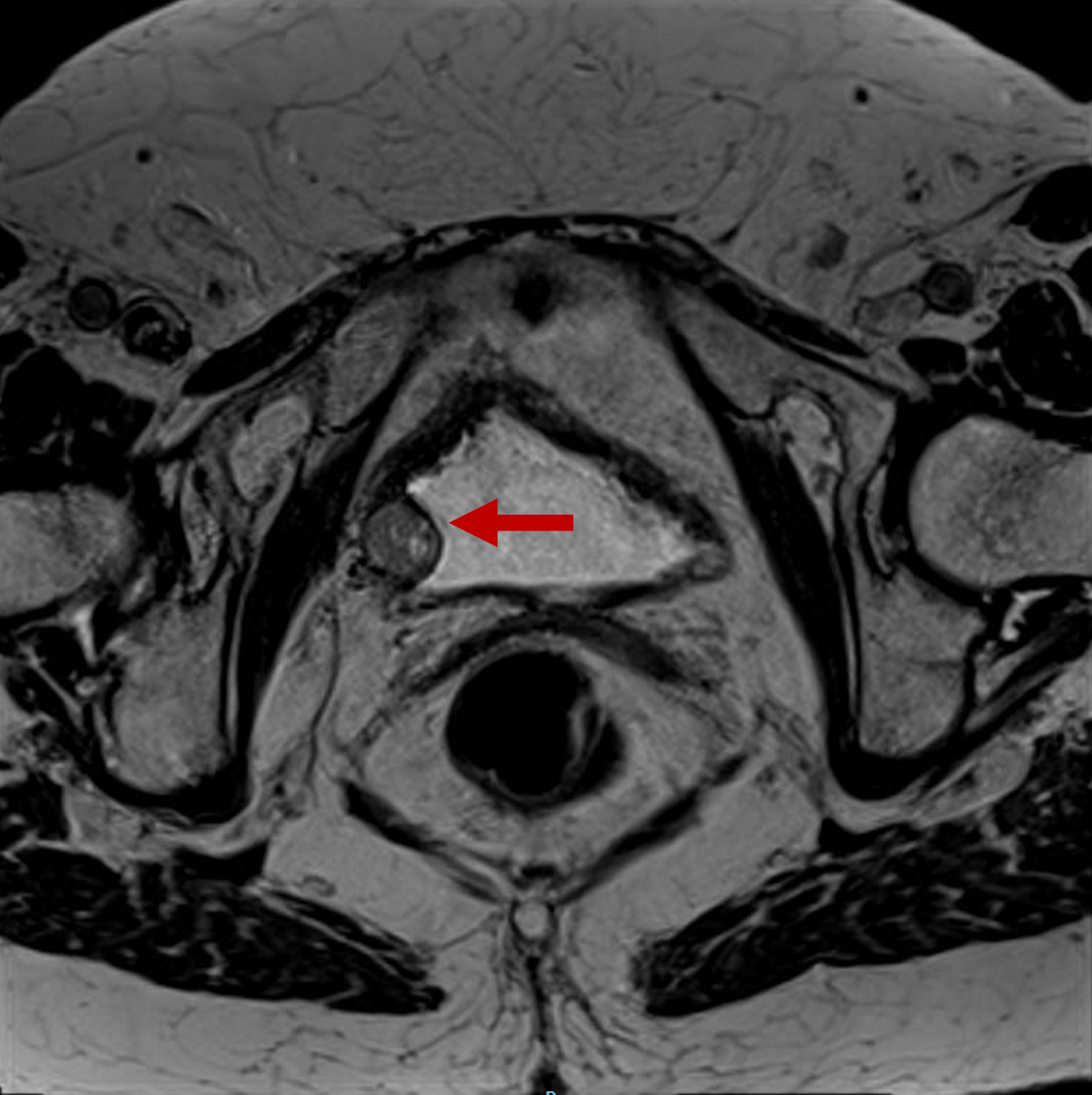

Cytology results were negative for urothelial carcinoma. Urine catecholamine levels were normal within the reference values of our laboratory, with a noradrenaline of 12.5 µg/L, adrenaline of 2.2 µg/L and dopamine of 65.3 µg/L. Bladder magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) described a solid tumor of nodular morphology and 15 mm arising from the right posterolateral margin of the bladder wall. It showed well-defined contours with no signs of intraluminal extension or extravesical involvement and absence of adenopathies (Fig. 2).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Bladder MRI requested to study the lesion found in the CT scan and ultrasound. The red arrow points to a solid tumor of nodular morphology of 15-mm depending on the right posterolateral margin of the bladder. It shows well-defined contours with no signs of intraluminal extension or regional fat involvement. MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CT: computed tomography. |

Examination under anesthesia revealed a 1.5-cm lesion in right lateral wall, which was protruding from the outside of the bladder walls, with no changes in the bladder mucosa.

Treatment

The lesion was excised; on gross section it appeared solid. We decided transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB) because of the small size of the tumor and the lack of clear signs suggestive of a BPGL. Histopathology report confirmed a BPGL.

Follow-up and outcomes

After TURB, the patient developed two episodes of urinary tract infection (UTI), both of which were successfully treated with fosfomycin and cefuroxime.

The case was presented to the Oncology Committee. The board recommended further evaluation, including plasma/urine catecholamines, genetic testing, a follow-up bladder MRI, and a metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy. MIBG scintigraphy showed a mild irregular thickening of the right lateral bladder wall (6 mm) at the resection site, without abnormal radiotracer uptake beyond physiological urinary excretion. No residual chromaffin tissue was detected. Exploration showed no pathological deposits or presence of chromaffin tissue. MRI reported no signs of tumor recurrence. Twenty-four-hour urinary metanephrines and catecholamines were within normal ranges. Genetic testing did not identify any pathogenic variants associated with susceptibility to pheochromocytoma and/or hereditary paraganglioma.

It was decided to follow up this patient with cystoscopy, bladder MRI and periodic clinical evaluations. Six months after surgery, the patient remained asymptomatic.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

BPGLs are extremely rare, resulting in limited literature to guide management. They have a propensity to be misdiagnosed due to several factors: their typical location in the bladder wall (often involving the muscularis propria), nonspecific symptoms, morphologic and immunohistochemical overlap with other tumors, and overall rarity [6].

The first and the most critical part of the diagnosis is clinical suspicion. We should think of this unusual tumor when practically everything else is ruled out. We would see macroscopic hematuria (50-60%) [2, 4, 5], symptoms related to catecholamine release (40-50%) such as paroxysmal hypertension, palpitations or tachycardia, headache, and anxiety [3, 4, 7]. Notably, about 20% of patients exhibit the classic micturition attack - a triad of hypertensive crisis, palpitations with sweating, and a fainting sensation triggered by urination [2, 4, 8, 9]. However, up to 20% of cases may be entirely asymptomatic [3, 4, 8, 9].

Cystoscopy usually is the first investigation when a bladder tumor is suspected, although it is not without risk; instrumentation and overdistension of the bladder can precipitate catecholamine release and adrenergic crisis in a patient with BPGL. The typical appearance on cystoscopy is of a small, rounded tumor that is submucosal, such as the one observed in our patient [2].

It can be detected by different imaging tests, which can also help better characterize the lesion and its stage. These include Doppler ultrasound (US), which shows a solid hypervascular submucosal mass, with increased flow. CT can be used, with a hypervascular image with intense uptake in the arterial phase and rapid washout in the venous phase, which can help evaluate the local and lymph node extension. MRI has excellent soft tissue contrast resolution and can identify the different layers of the bladder wall, enabling more accurate tumor localization. It typically shows a well-defined lesion with hyperintensity in T2 sequences and intense enhancement after gadolinium administration, which helps differentiate it from urothelial tumors. MIBG single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)/CT, historically the imaging gold standard for sympathetic paragangliomas, offers near-perfect specificity and remains valuable, although its sensitivity is modest and a negative study does not exclude tumor presence [2, 4].

The main differential diagnosis for a small, well-defined, rounded or oval, submucosal or intramural bladder mass is a leiomyoma, which can mimic BPGL on US and CT, highlighting the importance of MRI and histopathological examination of the tumor [2].

The histopathologic differential diagnosis of BPGL is quite broad; first of all, it is critical to exclude urothelial carcinoma, as management differs markedly [5].

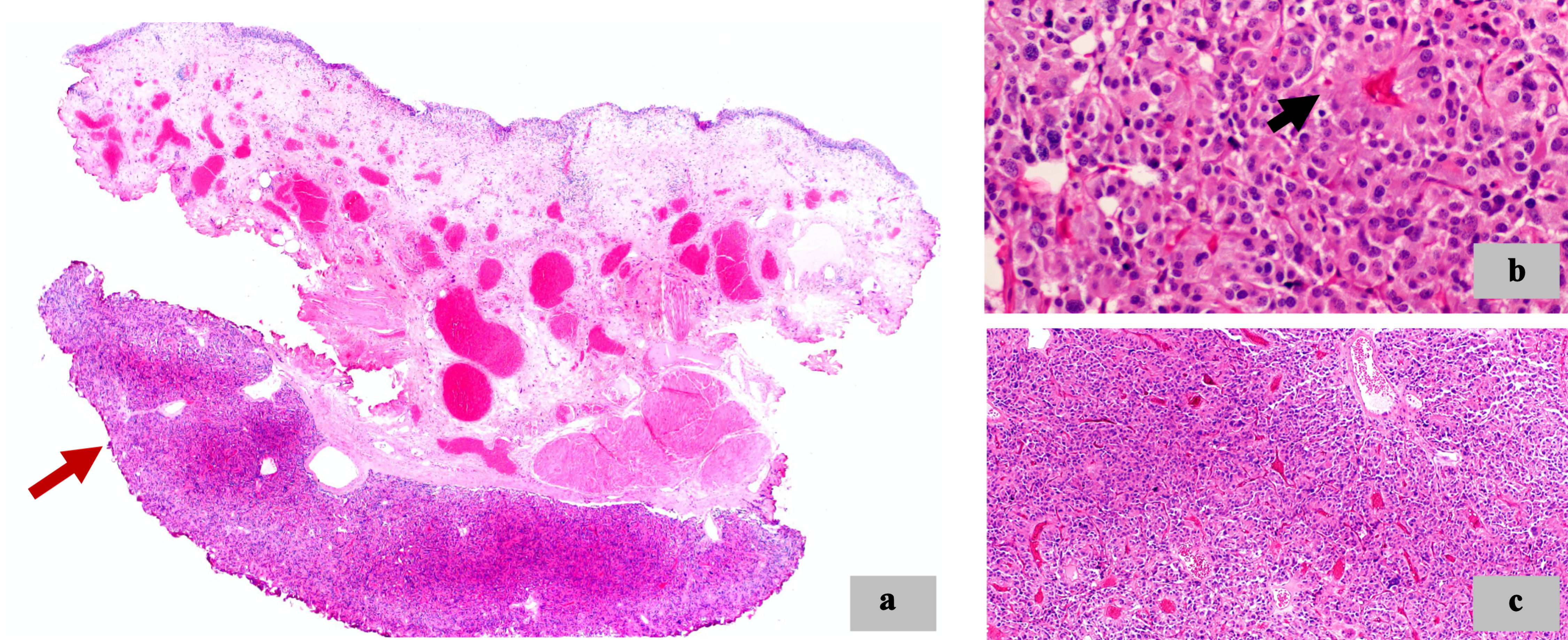

Microscopically, at low magnification, in the muscularis propria, we observed a neoplastic proliferation with multinodular architecture. At higher magnification, the neoplastic cells were organized in irregular nests and pseudorosette formation. The cells had granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and round to oval nuclei, some of which were large, hyperchromatic and with irregular contours. There was no desmoplastic reaction. A delicate fibrovascular stroma between the cells was identified (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Morphologic features. (a) Neoplastic proliferation with multinodular architecture (red arrow) in the muscularis propria of the bladder (× 2). (b) Pseudorosette formation (black arrow) (× 40). (c) Irregular nests architecture (× 10). |

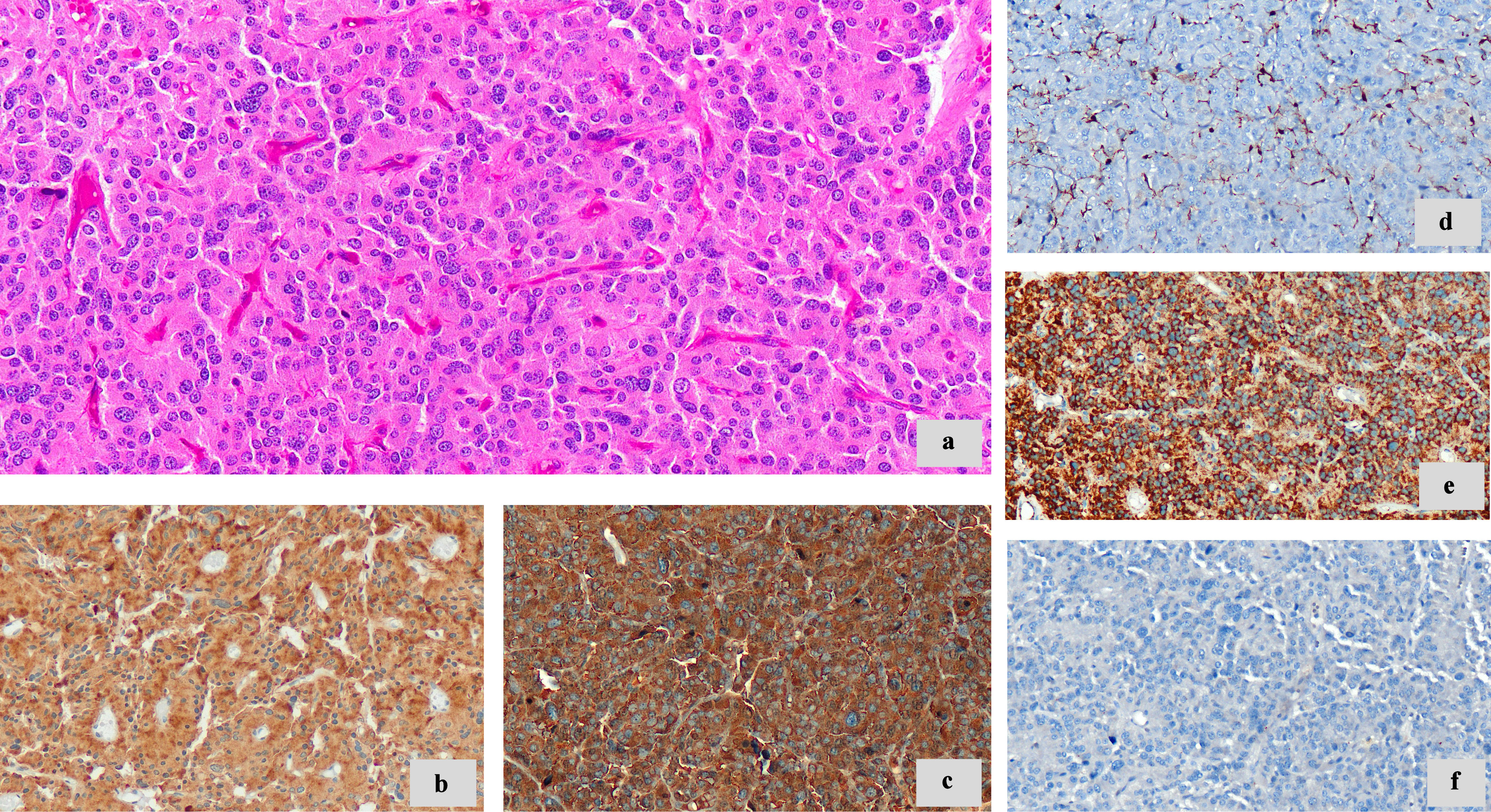

With immunohistochemical techniques, neoplastic cells showed diffuse and strong positivity for neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin and synaptophysin. S100 staining highlighted the sustentacular cells. Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (CKAE1/AE3) was negative. The cell proliferation index (Ki-67) was approximately 2%. Mitosis and necrosis were not observed (Fig. 4).

Click for large image | Figure 4. Morphologic features and immunohistochemistry techniques. (a) Neoplastic cells with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, round to oval nuclei (× 20). (b) Synaptophysin (diffuse cytoplasmic staining) (× 20). (c) Chromogranin A (diffuse cytoplasmic staining) (× 20). (d) S100 highlights sustentacular cells (× 20). (e) SDHB immunoreactivity retained (× 20). (f) CKAE1/AE3 negative (× 20). SDHB: succinate dehydrogenase B; CKAE1/AE3: cytokeratin AE1/AE3. |

There are no histological hallmarks or biomarkers that can predict the behavior of pheochromocytomas [10, 11]. A loss of succinate dehydrogenase B (SDHB) immunoreactivity in tumor cells supports a diagnosis of SDH-related disease [12, 13]. SDHB mutations predominate in thoracic and abdominal paragangliomas, which in turn could be associated with a higher rate of recurrences and malignancy [4].

Imaging is essential to aid surgical planning, as endoscopic resection is often not possible or incomplete due to tumor location [2].

Small paragangliomas (< 3 cm), such as the one we are discussing, are usually treated with TURB, often due to the lack of awareness that it is a BPGL before surgery. In bigger tumors partial cystectomy (muscular invasion) or radical cystectomy (multifocal, with deep or lymph node invasion) is needed [2, 5, 9]. However, with TURB, there is evidence of a higher rate of recurrences, metastasis and paraganglioma-related death in young patients (mean age 45 years), female sex and stage ≥ T3 [4].

Recently, robotic partial cystectomy was successfully performed in a patient, without any intraoperative or postoperative complication, by Shekhda et al [14].

As we can see, the evidence is not conclusive, so the decision must be individualized according to the characteristics of the tumor and the experience of the center.

In cases of metastatic or unresectable BPGL, systemic therapies are indicated - including radioligand therapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, or chemotherapy. The optimal choice is case-dependent and often discussed in a multidisciplinary context.

Preoperative adrenergic blockade is essential to avoid perioperative hypertensive crises, especially in patients with catecholamine-secreting paragangliomas [3, 4]. As noted by Withey et al, and in accordance with the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) guidelines, it should begin at least 10 - 14 days before intervention, including those with normal catecholamine levels [2].

In retrospect, it is worth asking whether there were indications to suspect the diagnosis prior to resection. Our patient did not present typical adrenergic symptomatology, which illustrates the diagnostic difficulty. Preoperative diagnosis rates before initial surgery for PUBs remain suboptimal, ranging from 34% to 46.4%, affecting the presurgical management of these tumors [9].

Given that the risk of recurrence is 16-20% at 10 years, postoperative follow-up is recommended [2, 5]. Notably, BPGL metastases can develop many years after initial presentation, even after complete resection of the primary tumor [2].

There is no clear consensus on how this should be done. Other authors recommend cystoscopy and urinary cytology every 3 - 6 months for the first 2 years and annually thereafter [4]; plasma and urinary metanephrines annually [3, 4, 6]; and MRI or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT every 1 - 2 years in high-risk patients [2, 4]. Some authors advocate on MRI to minimize radiation exposure in these patients on long-term surveillance, and additionally lifelong follow-up is recommended [2].

In conclusion, this case report highlights the importance of considering BPGL as part of the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with post-micturition symptoms and paroxysmal hypertension. Consideration should be given to preoperative medical management with alpha-blockers to reduce the risk of intraoperative catecholamine crisis and favorable clinical outcomes during and after surgery. This case highlights the need for a multidisciplinary team to assess these cases, including endocrinology, radiology, nuclear medicine, general, urology and pathology.

Learning points

BPGL should be included in the differential diagnosis of any bladder mass, especially when adrenergic symptoms or micturition-induced hypertensive crises are present. Yet the tumor may also be entirely silent - as in our patient - so clinicians must keep a broad differential diagnosis, even in atypical scenarios.

Preoperative recognition is essential to ensure proper perioperative planning and to avoid life-threatening catecholamine crises. Given the tumor’s nonspecific clinical and imaging features, a high index of suspicion, targeted biochemical testing and careful image interpretation are required to establish the diagnosis before intervention.

Optimal management is multidisciplinary. Close collaboration among urologists, endocrinologists, radiologists, pathologists and geneticists enables comprehensive assessment, detection of hereditary syndromes and selection of the most appropriate surgical strategy and follow-up schedule.

Although no universal surveillance protocol exists, long-term - and preferably lifelong - follow-up is strongly advised, because late local recurrence or distant metastasis can occur. Regular cystoscopy, cross-sectional imaging and biochemical monitoring tailored to individual risk factors facilitate early detection and improve outcomes

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

The patient in this case has provided oral consent for publication.

Author Contributions

ICD contributed to the writing of the case report, preparation of the figures, revisions, and management of the submission process. JEHS participated in patient care and contributed to the writing of the case report and revisions and continued to see the patient as her urologist. OBP contributed to the writing of the case report and revisions, and the analysis of anatomopathological images.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

BPGL: bladder paraganglioma; TURB: transurethral resection of the bladder; CT: computed tomography; LUTS: lower urinary tract symptoms; ECG: electrocardiogram; US: ultrasound; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PGL/PCC: paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma; VHL: von Hippel-Lindau; MEN2: multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2; NF1: neurofibromatosis type 1; UTI: urinary tract infection; MIBG: metaiodobenzylguanidine; SDHB: succinate dehydrogenase B; CKAE1/AE3: cytokeratin AE1/AE3; Ki-67: proliferation marker Ki-67; PET-CT: positron emission tomography-computed tomography

| References | ▴Top |

- Bharti JN. Urinary bladder paraganglioma- a noteworthy, rare entity. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar). 2024;20(2):236-238.

doi pubmed - Withey SJ, Christodoulou D, Prezzi D, Rottenberg G, Sit C, Ul-Hassan F, Carroll P, et al. Bladder paragangliomas: a pictorial review. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2022;47(4):1414-1424.

doi pubmed - Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of paragangliomas. UpToDate. 2023.

- Pelegrin-Mateo FJ, Segui-Moya E, Fernandez-Cruz M, Garcia-Segui A, De Nova-Sanchez E, Sanchez-Heras AB. [Bladder paraganglioma: Report of two cases and a literature review.]. Arch Esp Urol. 2021;74(4):445-449.

pubmed - Bicak T, Ozekinci S, Bicak Y, Daggulli M. Paraganglioma of urinary bladder: a case report. New J Urol. 2023;18(3):258-263.

- Co JL, Goco MLL, So JS. Paraganglioma in the urinary bladder: a pitfall in histopathologic diagnosis. Acta Med Indones. 2023;55(1):95-100.

pubmed - Daniels Garcia M, Manjarres Figueredo P, Macia Carrasquilla J, Garcia-Bermejo R. Paraganglioma vesical en un paciente pediatrico: reporte de caso y revision de bibliografia. Rev Esp Endocrinol Pediatr. 2024;15(1):33-35.

doi - Li W, Wei W, Yuan L, Zhang Y, MinYi. Clinicopathological features analysis of Paraganglioma of urinary bladder: A retrospective study. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2025;77:152477.

doi pubmed - Lou Y, Fan L, Hou X, Dominiczak AF, Wang JG, Staessen JA, Almustafa B, et al. Paroxysmal hypertension associated with urination. Hypertension. 2019;74(5):1068-1074.

doi pubmed - Asa SL, Ezzat S, Mete O. The diagnosis and clinical significance of paragangliomas in unusual locations. J Clin Med. 2018;7(9):280.

doi pubmed - Mete O, Tischler AS, de Krijger R, McNicol AM, Eisenhofer G, Pacak K, Ezzat S, et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with pheochromocytomas and extra-adrenal paragangliomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(2):182-188.

doi pubmed - Gill AJ, Benn DE, Chou A, Clarkson A, Muljono A, Meyer-Rochow GY, Richardson AL, et al. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB triages genetic testing of SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD in paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndromes. Hum Pathol. 2010;41(6):805-814.

doi pubmed - van Nederveen FH, Gaal J, Favier J, Korpershoek E, Oldenburg RA, de Bruyn EM, Sleddens HF, et al. An immunohistochemical procedure to detect patients with paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma with germline SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD gene mutations: a retrospective and prospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(8):764-771.

doi pubmed - Shekhda KM, Palan JM, Albor CB, Wan S, Chung TT. A rare case of bladder paraganglioma treated successfully with robotic partial cystectomy. Endocr Oncol. 2025;5(1):e240044.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.