| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 4, April 2025, pages 146-152

Double Trouble in the Pericardium: A Rare Co-Infection of Tuberculosis and Tularemia Leading to Cardiac Tamponade

Barbara Okekea, e, Ciri Pochab, Lanerica Rogersa, Amber Stefanskib, Christian Hendrixc, Chien-Jung Lind

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, St. Louis University Hospital, St. Louis, MO, USA

bSaint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA

cDepartment of Infectious Disease, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA

dDivision of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, St. Louis University Hospital, St. Louis, MO, USA

eCorresponding Author: Barbara Okeke, Department of Internal Medicine, St. Louis University Hospital, St. Louis, MO 63104, USA

Manuscript submitted February 27, 2025, accepted April 15, 2025, published online April 22, 2025

Short title: Cardiac Tamponade due to TB and Tularemia Co-Infection

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5124

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Cardiac tamponade attributed to co-infection with multiple pathogens is rare. A 40-year-old man who migrated from India 10 years prior with no medical history presented with a progressive dyspnea, night sweats, intermittent fevers, weight loss over a 3-month period, and a cough. An echocardiogram revealed cardiac tamponade and further biopsy revealed necrotizing granulomas with diffuse necrotic lymphadenopathy. Early anchoring bias led to an extensive tuberculosis (TB) workup which was initially negative. However, after broadening the differential, a co-infection of tularemia and latent extrapulmonary TB was identified as the etiology of cardiac tamponade. While tularemia in the setting of immunodepression has been identified as a cause for pericarditis, there is no current literature of a tularemia and TB co-infection causing cardiac tamponade. This case highlights the importance of expanding a differential diagnosis when the presentation does not fit the diagnosis, especially when a delay in management can be consequential.

Keywords: Tularemia; Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Cardiac tamponade; Pericardial effusion; Necrotizing granuloma

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Pericardial effusions have diverse etiologies, with malignancy, uremia, and infection among the most common causes [1-5]. Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening complication of pericardial effusion that requires urgent intervention (pericardial drainage) [6-9]. While tuberculous pericarditis [10-12] is a well-established cause of pericardial effusion (especially in regions where tuberculosis is endemic), tularemia (Francisella tularensis infection) is an exceedingly rare etiology. We present the first documented case of co-infection with F. tularensis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis manifesting as pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 40-year-old man who immigrated from India 10 years prior with no significant past medical history presented with 3 months of progressive dyspnea, night sweats, intermittent fevers, cough, loss of appetite, and significant weight loss. He denied recent travel, known sick contacts, or relevant occupational exposures.

On admission, he appeared diaphoretic and was tachycardic (115 bpm). A chest X-ray revealed a moderate right pleural effusion and associated right basilar atelectasis. Initial laboratory studies showed mild electrolyte abnormalities, including hyponatremia (131 mmol/L), hypokalemia (3.3 mmol/L), hypocalcemia (6.1 mg/dL), and mildly elevated aspartate aminotransferase (48 U/L). Initial cardiac evaluation including troponin and brain natriuretic peptide was normal, and electrocardiogram was remarkable only for sinus tachycardia. Initial transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) on admission showed a moderate pericardial effusion without tamponade physiology.

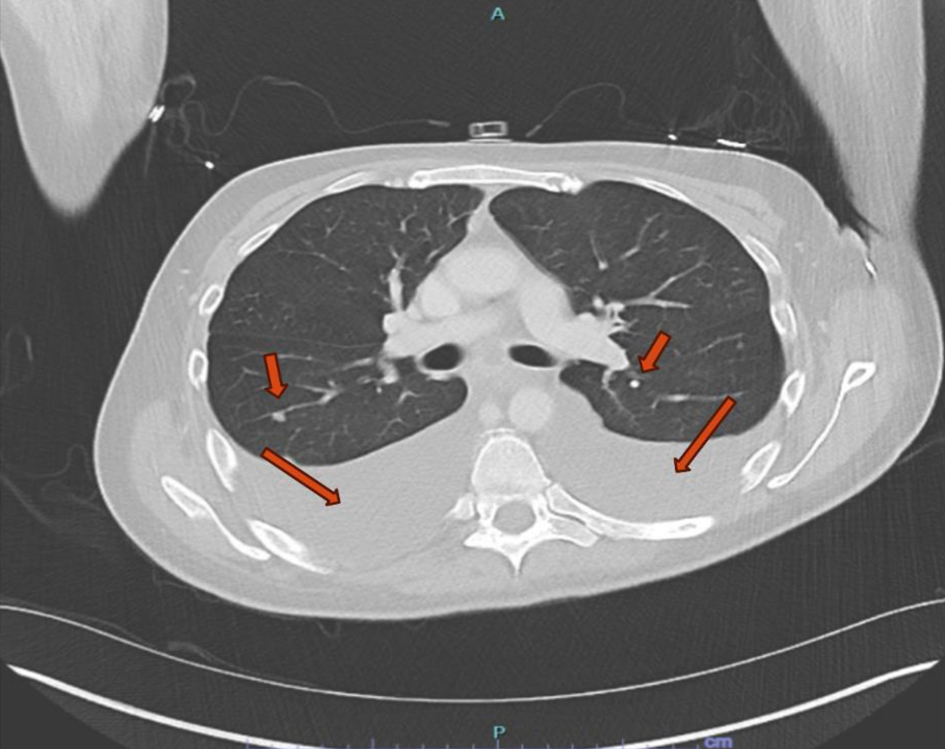

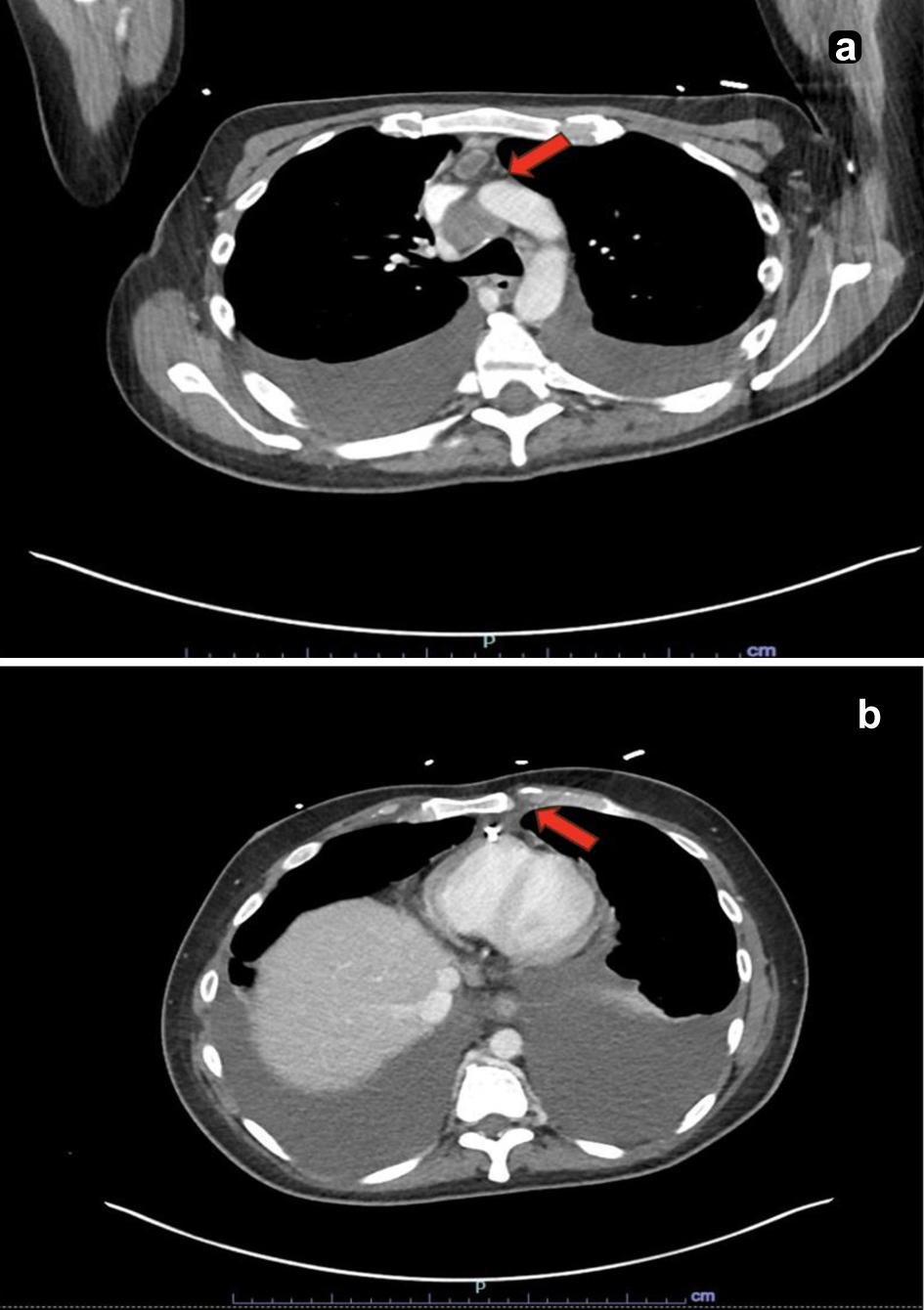

Due to elevated D-dimer (12.69 µg/mL FEU) and worsening respiratory status, computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiogram was performed, ruling out pulmonary embolism but revealing right pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, a pulmonary nodule, nodular peritoneal thickening, omental infiltration, and extensive mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (Figs. 1 and 2), suggestive of metastatic malignancy or granulomatous disease. Thoracentesis yielded 1.2 L of serosanguinous fluid, with analysis notable for exudative characteristics: total cell count 1,079 × 106/L (17% neutrophils, 55% lymphocytes), glucose 75 mg/dL, pH 7.57, lactate dehydrogenase 634 U/L, protein 4.4 g/dL, red blood cell (RBC) 12 × 106/L, and elevated adenosine deaminase (ADA) at 48 U/L. Initial microbiological studies, including M. tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction (MTB-PCR), Gram stain, bacterial and fungal cultures, and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smears, were negative. Subsequent labs were notable for metabolic disturbances (persistent hypocalcemia, hypoglycemia, hypomagnesemia), undetectable vitamin D (< 3.5 ng/mL), and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein 3.62 mg/dL and lactate 3.2 mmol/L). Malignancy markers (carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)) were unremarkable.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Computed tomography scan of the chest. Large bilateral pleural effusions with adjacent atelectasis and scattered pulmonary nodules (red arrows). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Computed tomography scan of the chest. (a) Enlarged lymph node within the anterior mediastinum measuring up to 1.0 cm in the short axis with central hypodensity concerning for necrosis (red arrow). (b) An enlarged retro-crural lymph node measuring up to 0.9 cm in the short axis (red arrow). |

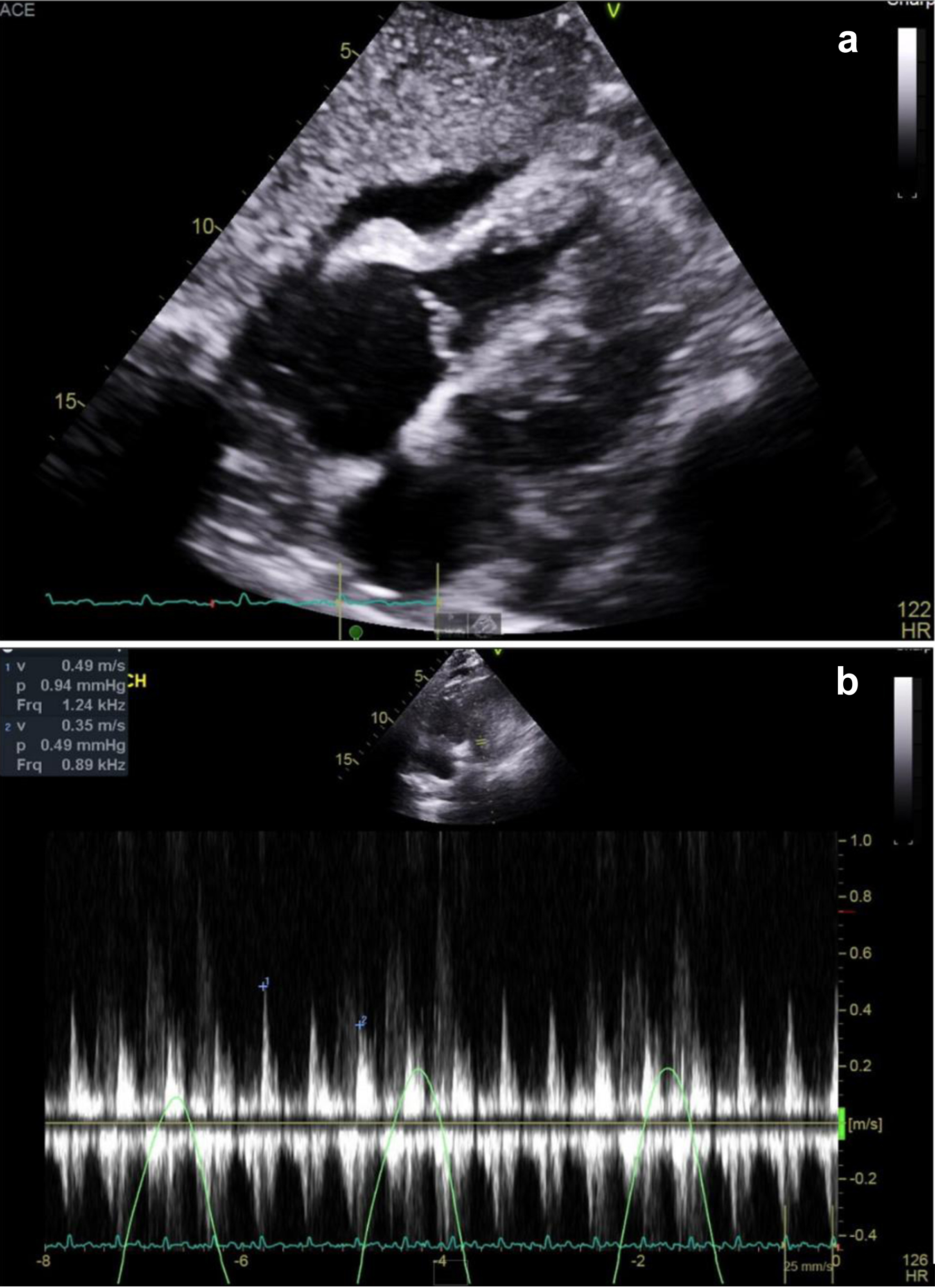

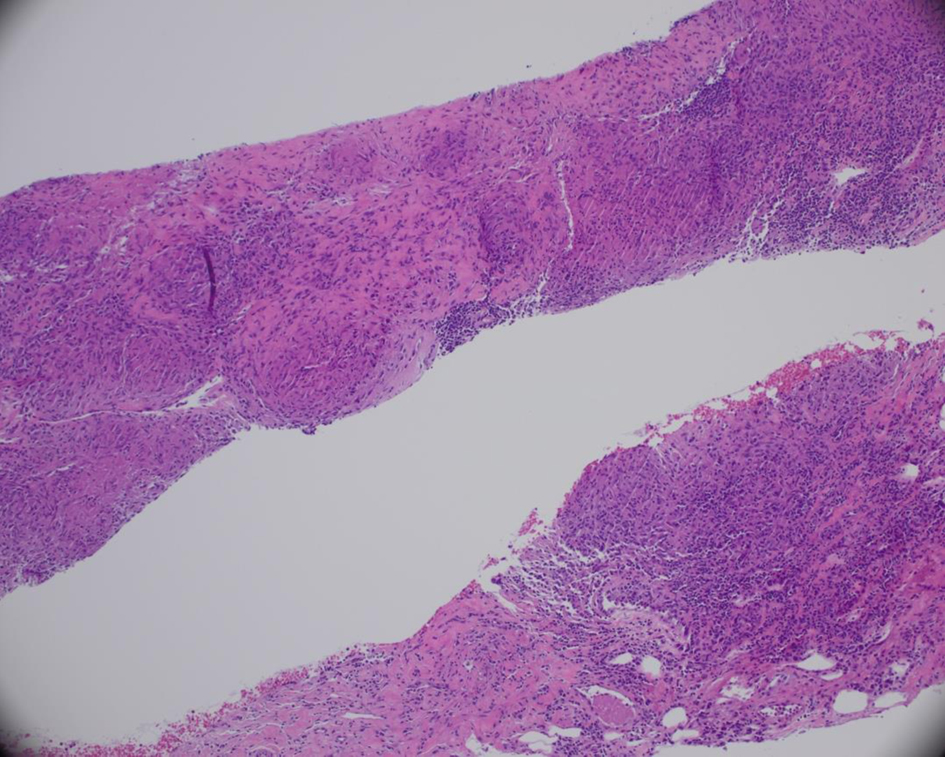

The patient continued to deteriorate, developing hypotension, high-grade fevers (up to 102.3 °F), severe tachycardia (160 bpm), and acute respiratory distress. Repeated TTE demonstrated rapidly progressing pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology (Fig. 3; Supplementary Material 1, jmc.elmerpub.com), requiring two urgent pericardiocenteses followed by a surgical pericardial window placement. Histopathology obtained by surgery from the retroperitoneal lymph nodes and pericardial biopsies revealed necrotizing granulomas (Fig. 4). Throughout the hospital stay, extensive infectious, autoimmune, and rheumatologic evaluations were largely negative or noncontributory. Though the QuantiFERON-gold was initially negative, the clinical suspicion of tuberculosis (TB) remained, thus prompting a consult to Infection Disease for concerns of culture-negative TB. In addition, we pursued other infectious causes of granulomatous diseases and agglutination serologies showed elevated F. tularensis antibodies (IgM 48 U/mL, antibody titer rising from 1:80 to 1:160).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Transthoracic echocardiography and mitral inflow velocities at pulsed wave Doppler. (a) Transthoracic echocardiogram showing anterior pericardial effusion. RV diastolic collapse was seen, indicating tamponade physiology. (b) Pulsed wave Doppler showing exacerbated mitral inflow respiratory variance. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Retroperitoneal lymph node biopsy. A hematoxylin and eosin-stained section of a retroperitoneal lymph node core biopsy showing granulomatous necrotizing lymphangitis. |

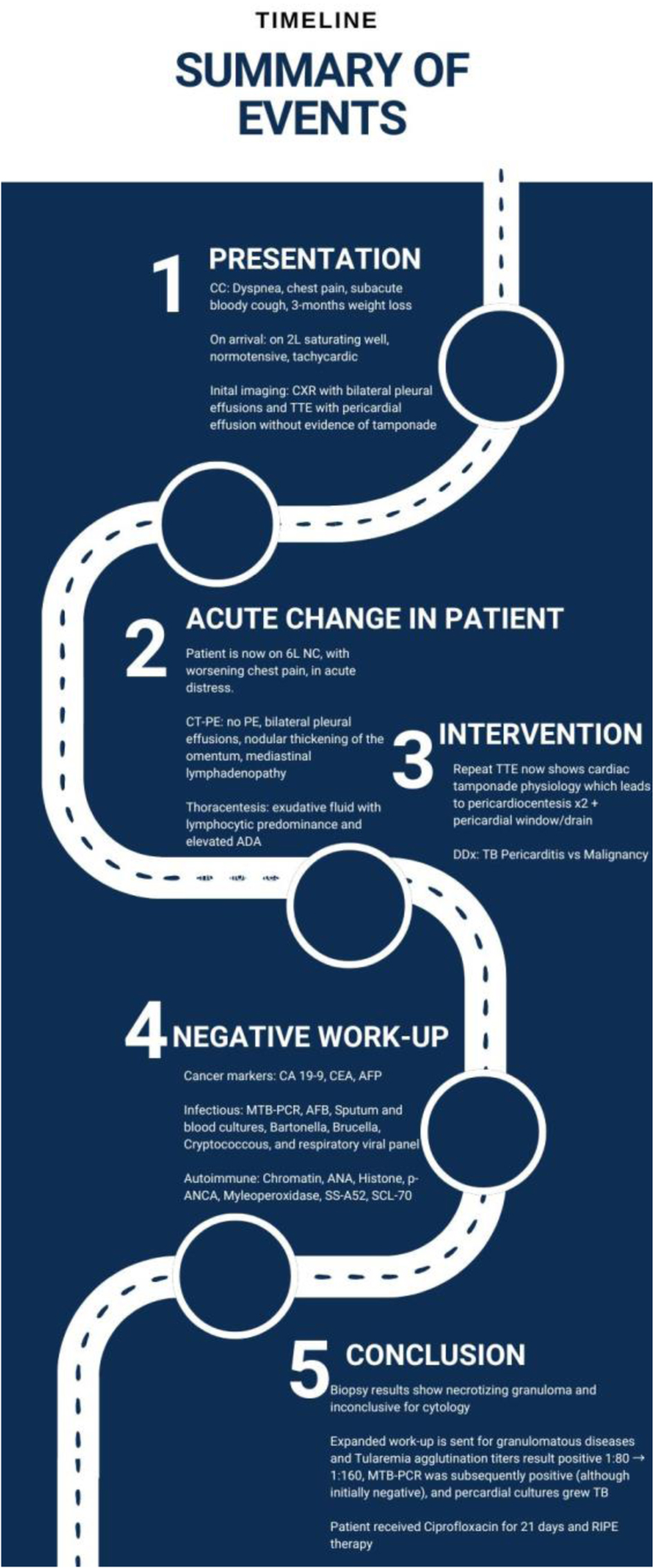

The patient was empirically treated with a 21-day course of ciprofloxacin for tularemia. Approximately 6 weeks after presentation, repeat pleural fluid studies ultimately returned positive for MTB-PCR, confirming concomitant TB. He subsequently started a 6-month rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RIPE) therapy regimen (Fig. 5).

Click for large image | Figure 5. Summary chart of events. A flowsheet to summarize the patient’s hospitalization. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case represents an unprecedented co-infection of M. tuberculosis and F. tularensis (tularemia) causing pericardial effusion with progression to cardiac tamponade. To our knowledge, no prior report has documented TB and tularemia concurrently infecting the pericardium. Analysis of the pericardial fluid, along with pericardial tissue revealing necrotizing granulomas, a hallmark of granulomatous infection, immediately raised suspicion for tuberculous pericarditis [13]. Recognizing these granulomas was diagnostically valuable - their presence effectively ruled out purely idiopathic or viral pericarditis and directed our workup toward specific infections.

An unexpected aspect of this case was the identification of F. tularensis as a co-infecting pathogen. Tularemia is a zoonotic infection that is exceedingly rare as a cause of pericardial disease [14]. Our patient’s epidemiological background (residence in a tularemia-endemic area of the Midwest) and clinical course prompted us to broaden the infectious workup beyond TB. Serological testing for tularemia was obtained given the patient’s potential exposure risk and the presence of necrotizing granulomas, and infection was confirmed. F. tularensis has rarely been reported as an agent of pericarditis, usually only in the setting of severe systemic tularemia (typhoidal form) or as a complication of tularemic pneumonia [14]. More recent case reports have noted that pericardial effusion can occasionally be the sole manifestation of tularemia [14]. In our patient, it is conceivable that an initial pulmonary tularemia (or a silent bacteremic phase) seeded the pericardium. Pathophysiologically, tularemia can cause granulomatous inflammation in involved organs much like TB; in fact, tularemic lesions may caseate and can be mistaken for TB on histology [15, 16]. This granulomatous response provides a plausible mechanism for how F. tularensis infection led to the initial pericardial effusion - the intense immune reaction and tissue necrosis in the pericardium likely contributed to fluid accumulation and pericardial inflammation. Additionally, F. tularensis is an intracellular pathogen that evades early detection; it is fastidious and often cannot be grown on standard culture media [14]. Thus, diagnosis of tularemia typically relies on serology or specialized culture techniques.

In this case, initial TB studies, including MTB-PCR and AFB smears, were negative, delaying empiric TB therapy. Pericardial fluid analysis showed features consistent with TB, including an exudative, lymphocyte-rich effusion (often seen in tuberculous pericarditis) and was notable for an elevated ADA level [17, 18]. An ADA above about 35 U/L in pericardial fluid is highly suggestive of TB infection (sensitivity about 90%, specificity about 70%) [19]. Although direct identification of M. tuberculosis from pericardial fluid is notoriously difficult due to the paucibacillary nature of the fluid (smears are frequently negative and cultures can take weeks) [19], our diagnostic strategy included both molecular testing and culture. In this case, nucleic acid amplification testing aided in pointing to TB as a subsequent infection, while pericardial fluid culture ultimately grew M. tuberculosis. This fulfills the criteria for definite tuberculous pericarditis (demonstration of the organism in pericardial fluid/tissue) that ultimately led to tamponade and guided us in tailoring therapy. The early initiation of appropriate therapy in our patient likely contributed to a favorable outcome and highlights that early consideration of TB in pericardial effusions saves lives [19].

Direct evidence that F. tularensis infection triggers reactivation of latent M. tuberculosis is lacking; however, there is biologic plausibility for such an interaction. Both tularemia and TB are intracellular, granulomatous infections that rely on robust T helper-1 immune responses (interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α) for containment [20, 21]. Severe infections with tularemia can cause intense systemic inflammation followed by immune dysregulation, which might compromise the host’s ability to keep latent TB in check. Analogous scenarios have been observed in other infections (e.g., severe COVID-19), where an acute infectious insult and the accompanying immune perturbation preceded reactivation of latent TB [22]. It is therefore plausible that the inflamed microenvironment and transient immune imbalance caused by tularemia could unmask a quiescent TB focus, for example, tipping a latent pericardial TB infection into active disease. While co-infection of tularemia and reactivated TB is exceedingly rare, the overlapping immune requirements and inflammatory responses provide a credible mechanistic basis for tularemia exacerbating or revealing latent TB in an atypical location like the pericardium.

Serologic cross-reactivity between F. tularensis and other bacteria (e.g., Brucella and Yersinia species) is documented, potentially causing false-positive tularemia antibody results [23]. Notably, about 6-8% of patients with tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis in one endemic region had positive F. tularensis agglutination titers [24] and there are case reports of presumed tuberculous lymphadenitis later confirmed as tularemia by serology or PCR. For both acute and convalescent phases of the disease, paired serum samples showing a significant rise in antibody titers are considered diagnostic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends confirming cases of tularemia with a fourfold increase in specific antibody titers in paired serum samples or a single titer of 1:160 or greater in patients with compatible clinical symptoms [23]. Most diagnoses rely on serologic testing, but serology carries limitations, including the potential for cross-reactivity with other gram-negative organisms. In this case, the presence of necrotizing granulomas, a compatible clinical presentation, and lack of alternative confirmed infectious etiologies supported the diagnosis of active tularemia. However, the absence of confirmatory culture or PCR testing for F. tularensis limits the strength of this conclusion and must be acknowledged as a diagnostic limitation.

The coexistence of two unusual pericardial infections in this patient underscores several important lessons. First, it emphasizes the diagnostic importance of tissue pathology: finding necrotizing granulomas in pericardial specimens should trigger an aggressive search for infectious causes (especially TB) rather than attributing an effusion to idiopathic or autoimmune causes [13]. Early pericardial biopsy or fluid cytology can be invaluable when initial fluid studies are nondiagnostic, as it was in our patient. Second, this case illustrates the need for broad differential thinking. Even in regions with low TB prevalence, TB remains a key cause of granulomatous pericarditis and must be considered early. Conversely, even in a patient in whom TB is confirmed, one should remain vigilant for additional co-infections or atypical pathogens if the clinical picture is not fully explained. In retrospect, our patient’s exposure history and epidemiologic context (Midwestern United States, where tularemia sporadically occurs) were clues that an unusual zoonotic infection might be involved. By not anchoring solely on a single diagnosis, we discovered the tularemia co-infection and were able to treat it appropriately.

Conclusion

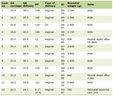

In summary, we report the first known case of concomitant tuberculous and tularemic pericarditis presenting as cardiac tamponade. Key diagnostic steps included prompt fluid drainage, meticulous pathological examination revealing caseating granulomas, and an expanded infectious workup that identified dual etiologies (Table 1) [25, 26]. This case highlights the importance of considering granulomatous infections early in the evaluation of atypical pericardial effusions and not hesitating to perform invasive diagnostic procedures when indicated. Tularemia, though an exceedingly rare cause of pericardial effusion, can mimic TB in its pathology and should be on the differential in patients with compatible exposures or when initial tests are inconclusive. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for TB in pericardial disease, while also remaining alert to less common co-infections. This novel case adds to the literature by highlighting an unusual dual infection and reinforces the principle that necrotizing pericardial granulomas warrant a thorough search for infectious culprits, sometimes more than one, to ensure timely, lifesaving treatment.

Click to view | Table 1. Causes of Granulomatous Disease [25, 26] |

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Transthoracic echocardiographic evidence of CT. Transthoracic echocardiogram showing anterior pericardial effusion where early RV diastolic collapse is seen indicating CT physiology.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

CJL is supported by American Heart Association Career Development Award 24CDA1277194.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest for this work.

Informed Consent

This case report was drafted with permission of the patient.

Author Contributions

Dr. Barbara Okeke primarily drafted this manuscript. Dr. Lanerica Rogers created the figures and tables and contributed to the discussion. Dr. Chien-Jung Lin helped with proofreading and oversaw manuscript creation. Amber Stefanski and Ciri Pocha both contributed to the background of the case.

Data AvailabilityAny inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.| References | ▴Top |

- Corey GR, Campbell PT, Van Trigt P, Kenney RT, O’Connor CM, Sheikh KH, Kisslo JA, et al. Etiology of large pericardial effusions. Am J Med. 1993;95(2):209-213.

doi pubmed - Sagrista-Sauleda J, Permanyer-Miralda G, Soler-Soler J. Tuberculous pericarditis: ten year experience with a prospective protocol for diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11(4):724-728.

doi pubmed - Levy PY, Corey R, Berger P, Habib G, Bonnet JL, Levy S, Messana T, et al. Etiologic diagnosis of 204 pericardial effusions. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82(6):385-391.

doi pubmed - Reuter H, Burgess LJ, Doubell AF. Epidemiology of pericardial effusions at a large academic hospital in South Africa. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133(3):393-399.

doi pubmed pmc - Ma W, Liu J, Zeng Y, Chen S, Zheng Y, Ye S, Lan L, et al. Causes of moderate to large pericardial effusion requiring pericardiocentesis in 140 Han Chinese patients. Herz. 2012;37(2):183-187.

doi pubmed - Doherty JU, Kort S, Mehran R, Schoenhagen P, Soman P, Dehmer GJ, Doherty JU, et al. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2019 Appropriate Use Criteria for Multimodality Imaging in the Assessment of Cardiac Structure and Function in Nonvalvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(4):488-516.

doi pubmed - Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, Baron-Esquivias G, Bogaert J, Brucato A, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(42):2921-2964.

doi pubmed pmc - Imazio M, Adler Y. Management of pericardial effusion. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(16):1186-1197.

doi pubmed - Beck CS. Two cardiac compression triads. JAMA. 1935;104(9):714-716.

doi - Kopcinovic LM, Culej J. Pleural, peritoneal and pericardial effusions - a biochemical approach. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2014;24(1):123-137.

doi pubmed pmc - Tuon FF, Litvoc MN, Lopes MI. Adenosine deaminase and tuberculous pericarditis—a systematic review with meta-analysis. Acta Trop. 2006;99(1):67-74.

doi pubmed - World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023.

- Ward M, Bates T, Qazi Z, DeMars B, Doynow D, Karki P, Calick D, et al. Tuberculous pericarditis: a rare cause of syncope in a young male. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024:209:A4234.

- Landais C, Levy PY, Habib G, Raoult D. Pericardial effusion as the only manifestation of infection with Francisella tularensis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:206.

doi pubmed pmc - Haholu A, Salihoglu M, Turhan V. Granulomatous lymphadenitis can also be seen in tularemia, not only in tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17(4):e283.

doi pubmed - Gun A, Bahadir B, Celeb G, Numanoglu G, Ozdamar SO, Mocan Kuzey G. Fine needle aspiration cytology findings in cases diagnosed as oropharyngeal tularemia lymphadenitis. Turk J Pathol. 2007;23(1):38-42.

- Reuter H, Burgess LJ, Carstens ME, Doubell AF. Adenosine deaminase activity - more than a diagnostic tool in tuberculous pericarditis. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2005;16(3):143-147.

pubmed - Xie DL, Cheng B, Sheng Y, Jin J. Diagnostic accuracy of adenosine deaminase for tuberculous pericarditis: a meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(22):4411-4418.

pubmed - Alotaibi N, Almutawa F, Alhazzaa A, Suliman I. Tuberculous pericarditis in an immunocompromised patient: a case report. Cureus. 2024;16(10):e71507.

doi pubmed pmc - Cowley SC, Elkins KL. Immunity to Francisella. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:26.

doi pubmed pmc - Yuk JM, Kim JK, Kim IS, Jo EK. TNF in human tuberculosis: a double-edged sword. Immune Netw. 2024;24(1):e4.

doi pubmed pmc - Dormans T, Zandijk E, Stals F. Late tuberculosis reactivation after severe COVID-19. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2024;11(5):004406.

doi pubmed pmc - Maurin M. Francisella tularensis, tularemia and serological diagnosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:512090.

doi pubmed pmc - Karabay O, Kilic S, Gurcan S, Pelitli T, Karadenizli A, Bozkurt H, Bostanci S. Cervical lymphadenitis: tuberculosis or tularaemia? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(2):E113-E117.

doi pubmed - Shah KK, Pritt BS, Alexander MP. Histopathologic review of granulomatous inflammation. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2017;7:1-12.

doi pubmed pmc - Arber DA. Lymph nodes. In: Goldblum JR, Lamps LW, McKenney JK, Myers JL, editors. Rosai and Ackerman’s Surgical Pathology. 11th ed. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier; 2018. p. 1530-1631. Accessed September 4, 2024. https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/book/3-s2.0-B9780323263399000378

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.