| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 1, January 2025, pages 28-36

Local Control of Conjunctival Malignant Melanoma by Proton Beam Therapy in a Patient With No Metastasis in Six Years From in Situ to Nodular Lesions

Toshihiko Matsuoa, b, i, Takeshi Ogatac, Takahiro Wakic, Takehiro Tanakad, Kota Tachibanae, Tomokazu Fujif, Takuya Adachig, Osamu Yamasakie, h

aRegenerative and Reconstructive Medicine (Ophthalmology), Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering in Health Systems, Okayama University, Okayama City 700-8558, Japan

bDepartment of Ophthalmology, Okayama University Hospital, Okayama City 700-8558, Japan

cDepartment of Radiology, Proton Beam Center, Tsuyama Chuo Hospital, Tsuyama City 708-0841, Japan

dDepartment of Pathology, Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Okayama University, Okayama City 700-8558, Japan

eDepartment of Dermatology, Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Okayama University, Okayama City 700-8558, Japan

fDepartment of Gastroenterological Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Okayama University, Okayama City 700-8558, Japan

gDepartment of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Okayama University Hospital, Okayama City 700-8558, Japan

hDepartment of Dermatology, Shimane University Faculty of Medicine, Izumo City 693-0021, Japan

iCorresponding Author: Toshihiko Matsuo, Regenerative and Reconstructive Medicine (Ophthalmology), Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering in Health Systems, Okayama University, Okayama City 700-8558, Japan

Manuscript submitted October 22, 2024, accepted November 19, 2024, published online December 1, 2024

Short title: Control of Conjunctival Malignant Melanoma

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc4351

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Conjunctival malignant melanoma is extremely rare, with no standard of care established at moment. Here we report a 65-year-old woman, as a hepatitis B virus (HBV) carrier, who presented concurrently a liver mass and lower bulbar conjunctival pigmented lesions in the right eye. Needle liver biopsy and excisional conjunctival biopsy showed hepatocellular carcinoma and conjunctival malignant melanoma in situ, respectively. The priority was given to segmental liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. In 1 year, she underwent second and third resection of bulbar conjunctival pigmented lesions, and the pathological examinations constantly showed melanoma in situ. In the course, she showed gradual widening of pigmented lesions to upper bulbar conjunctiva and lower palpebral conjunctiva and lower eyelid. About 2.5 years from the initial visit, the lower eyelid lesion was resected for a genomic DNA-based test of BRAF mutations which turned out to be absent, and then, she began to have intravenous anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1), nivolumab every 3 or 4 weeks. She developed iritis in the right eye with conjunctival melanoma as an immune-related adverse event, 3 months after the beginning of nivolumab, and so she used daily topical 0.1% betamethasone eye drops to control the intraocular inflammation. She showed no metastasis in 6 years of follow-up, but later in the course, 5 years from the initial visit, she developed abruptly a non-pigmented nodular lesion on the temporal side of the bulbar conjunctiva along the corneal limbus, accompanied by two pigmented nodular lesions in the upper and lower eyelids in a few months. She thus, underwent proton beam therapy toward the conjunctival melanoma and achieved the successful local control. Proton beam therapy is a treatment option in place of orbital exenteration, and multidisciplinary team collaboration is desirable to achieve better cosmetic and functional outcomes in conjunctival malignant melanoma.

Keywords: Ocular surface; Conjunctiva; Malignant melanoma; Proton beam therapy; Nivolumab, PD-1 inhibitor; Immune checkpoint inhibitor

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Malignant melanoma in the head and neck [1, 2] occurs not only in the cutaneous area but also in nasal and paranasal mucosa [3], conjunctival mucosa [4-7], and lacrimal sac mucosa [8] on rare occasions. Furthermore, malignant melanoma may arise from choroidal melanocytes and presents an intraocular mass [9]. Surgical treatment for malignancy in the head and neck often results in disfiguring features and other modalities of treatment such as radiotherapy could be considered from the cosmetic point of view. From the standpoint of function, the conjunctiva, as the eyeball-supporting tissue, is crucial for maintaining the ocular surface for vision and cannot be resected in a wide area. The vision or visual acuity which is maintained by the eyeball, conjunctiva and eyelids is important for daily living and working life of patients who show conjunctival melanoma or intraocular choroidal melanoma. To achieve better cosmetic and functional outcomes, proton beam therapy, in place of radical surgical resection, is a therapeutic option for head and neck cancer including malignant melanoma [7, 10-14], and has been covered by the reimbursement of national health insurance in Japan since April 2018.

Until now, local therapies reported for conjunctival melanoma have been cryotherapy which is directly applied to the surface lesion, as well as local chemotherapy with mitomycin C, 5-fluorouracil, or interferon alpha-2b in a topical application, in addition to local radiotherapy as described above [5, 6, 14, 15]. Among these different modalities of treatment, however, the standard of care for conjunctival melanoma has not been established at moment. In the present report, we followed for 6 years a woman with conjunctival melanoma in situ who showed no metastasis but later in the course developed abrupt nodular growth of conjunctival melanoma. She underwent proton beam therapy toward the conjunctival melanoma to obtain successful local control.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

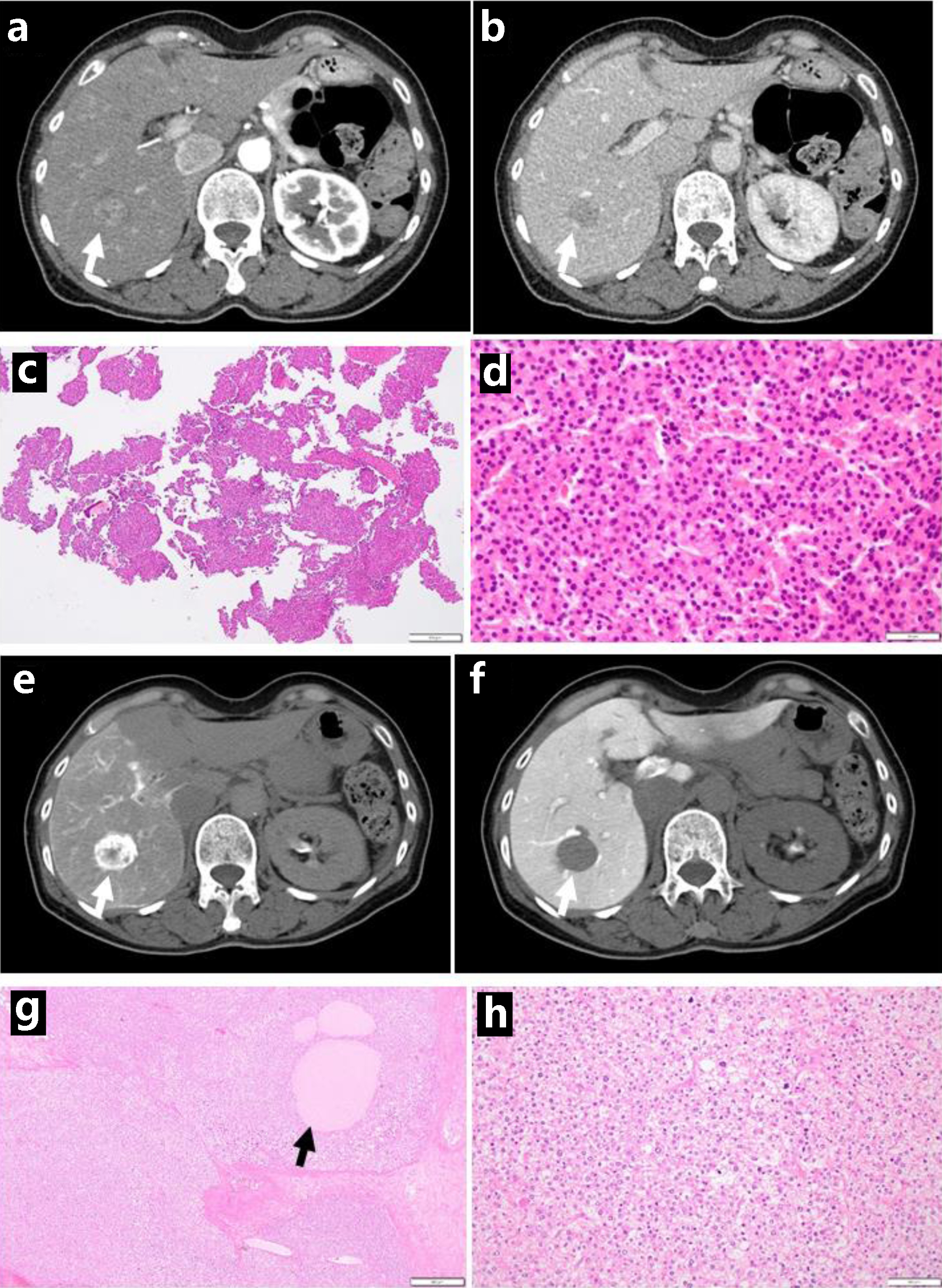

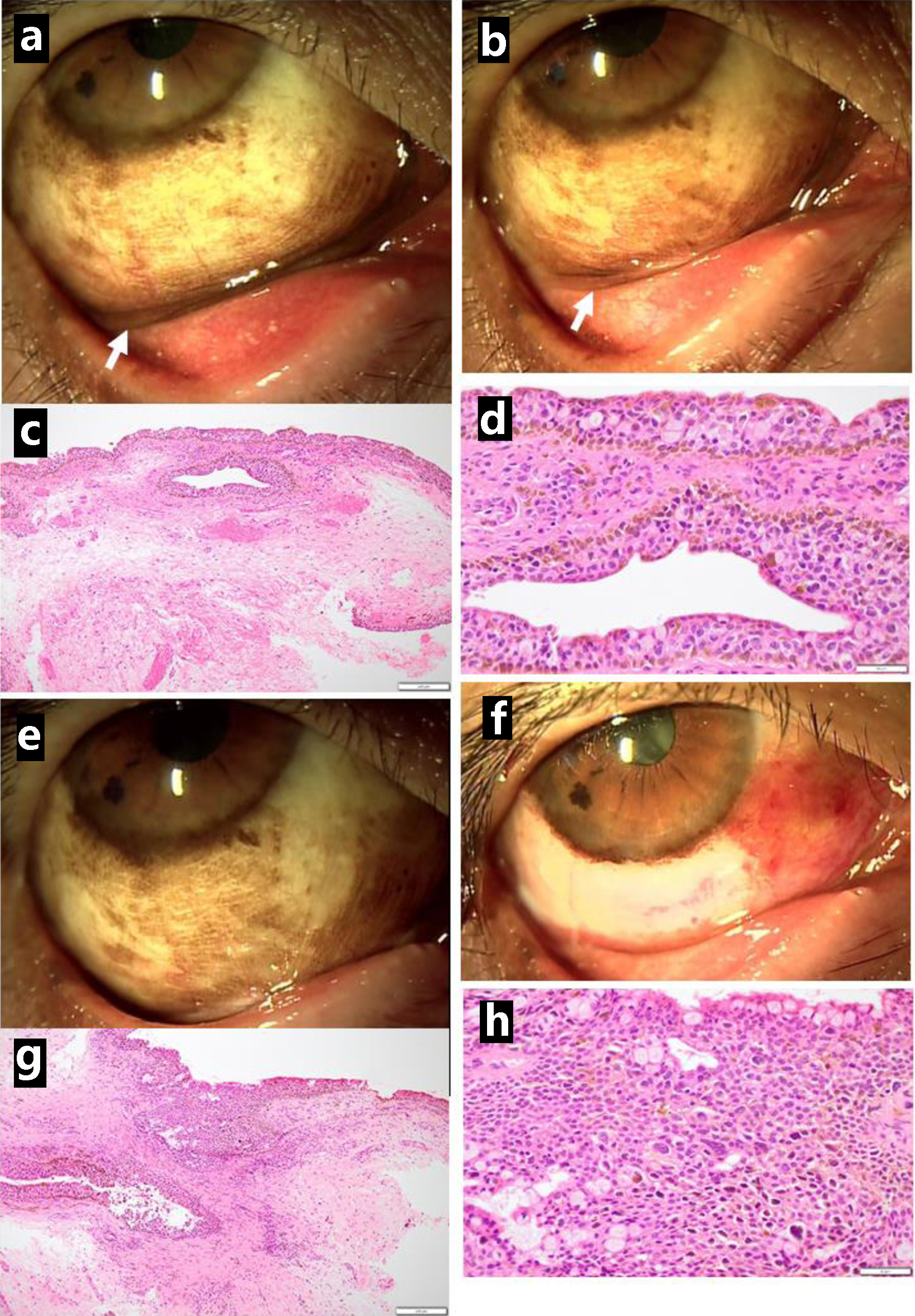

A 65-year-old woman noticed pigmentation of the lower conjunctival fornix in the right eye for the previous 4 years. The best-corrected visual acuity in decimals was 0.7 in the right eye and 0.8 in the left eye. The intraocular pressure was 14 mm Hg in both eyes. Moderate cataract was present in both eyes while the ocular fundus was normal in both eyes. In the past history, she had been detected as a hepatitis B virus (HBV) carrier at the age of 24 years in the delivery of the first child. At the age of 26 years in the delivery of the second child, she had temporary high fever and skin rashes, suspected of systemic lupus erythematosus. At this visit, she was referred to the University Hospital for treatment of a hepatic tumor which was detected by ultrasonography and computed tomography in the background of an elevated serum level at 172 mAU/mL of des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin (DCP, also known as protein induced by vitamin K absence/antagonist-II (PIVKA-II), normal range: 0 - 40 mAU/mL). The physical examinations detected nothing to be noted particularly. Blood examinations were all in the normal ranges except for markedly elevated hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) to 2,057 IU/mL and positive HBV-DNA at 2.1 LogIU/mL. Dynamic-enhanced computed tomography showed a spherical mass in hepatic segment VII (S7) in the diameter of 26 mm with early-phase staining (Fig. 1a) and late-phase washout (Fig. 1b), consistent with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Excisional biopsy of the lower conjunctival fornical lesion (Fig. 2a, b) in the right eye showed malignant melanoma in situ (Fig. 2c, d). A week later, needle liver biopsy revealed well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (Fig. 1c, d) which were positive for hepatocyte-specific antigen (anti-Hep-Par1, hepatocyte paraffin 1), and negative for melanoma triple cocktail-mix (anti-melanosome, HMB45; anti-MART1/melan A, A103; anti-tyrosinase, T311) antibodies.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Dynamic-enhanced computed tomography scans with enhancement at the initial visit, showing early-phase enhancement (arrow, a) and late-phase washout (arrow, b). Needle liver biopsy, showing hepatocellular carcinoma (c in low magnification, d in high magnification). Computed tomography during hepatic arteriography with marked staining (arrow, e), in contrast with computed tomography during arterial portography with no staining (arrow, f), consistent with hepatocellular carcinoma. Note foamy cells with degeneration (h) and necrotic cell debris spaces (arrow, g) after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, compared with viable tumor cells (d). Scale bar = 500 µm in c and g, 50 µm in d and h. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Pigmented lesions mainly along the lower conjunctival fornix (arrow, a) in the right eye just before excisional biopsy at the initial visit and reduced pigmented lesions in the fornix (arrow, b) one month later. Excisional biopsy showing conjunctival malignant melanoma in situ (c in low magnification, d in high magnification). Three months after the initial visit, the lower bulbar conjunctiva excised as wide as possible (presurgical photo in e, postsurgical photo in f). The excised tissue diagnosed as conjunctival malignant melanoma in situ (g in low magnification, h in high magnification). Scale bar = 200 µm in c and g, 50 µm in d and h. |

The priority was given to surgical treatment of the hepatic cancer. She showed early-phase filling (Fig. 1e) and no filling (Fig. 1f) in computed tomography during hepatic arteriography and arterial portography, respectively, indicative of hepatocellular carcinoma, and then, underwent transcatheter arterial chemoembolization using epirubicin-lipiodol mixture and gelatin sponge for presurgical treatment. One month later, she underwent posterior segmental resection of the liver. The pathology showed a 24 mm-diameter mass of moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (Fig. 1g, h) at stage II (T2N0M0). Foamy degenerative cells and necrotic cell debris spaces were present after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. She began to have oral edoxaban 30 mg daily, based on her body weight, for postsurgical bilateral ovarian vein thrombosis. Two weeks later, she underwent a second surgery to extirpate the lower bulbar conjunctival pigmented lesions as wide as possible (Fig. 2e, f) in the right eye, leading again to pathological diagnosis of malignant melanoma in situ (Fig. 2g, h).

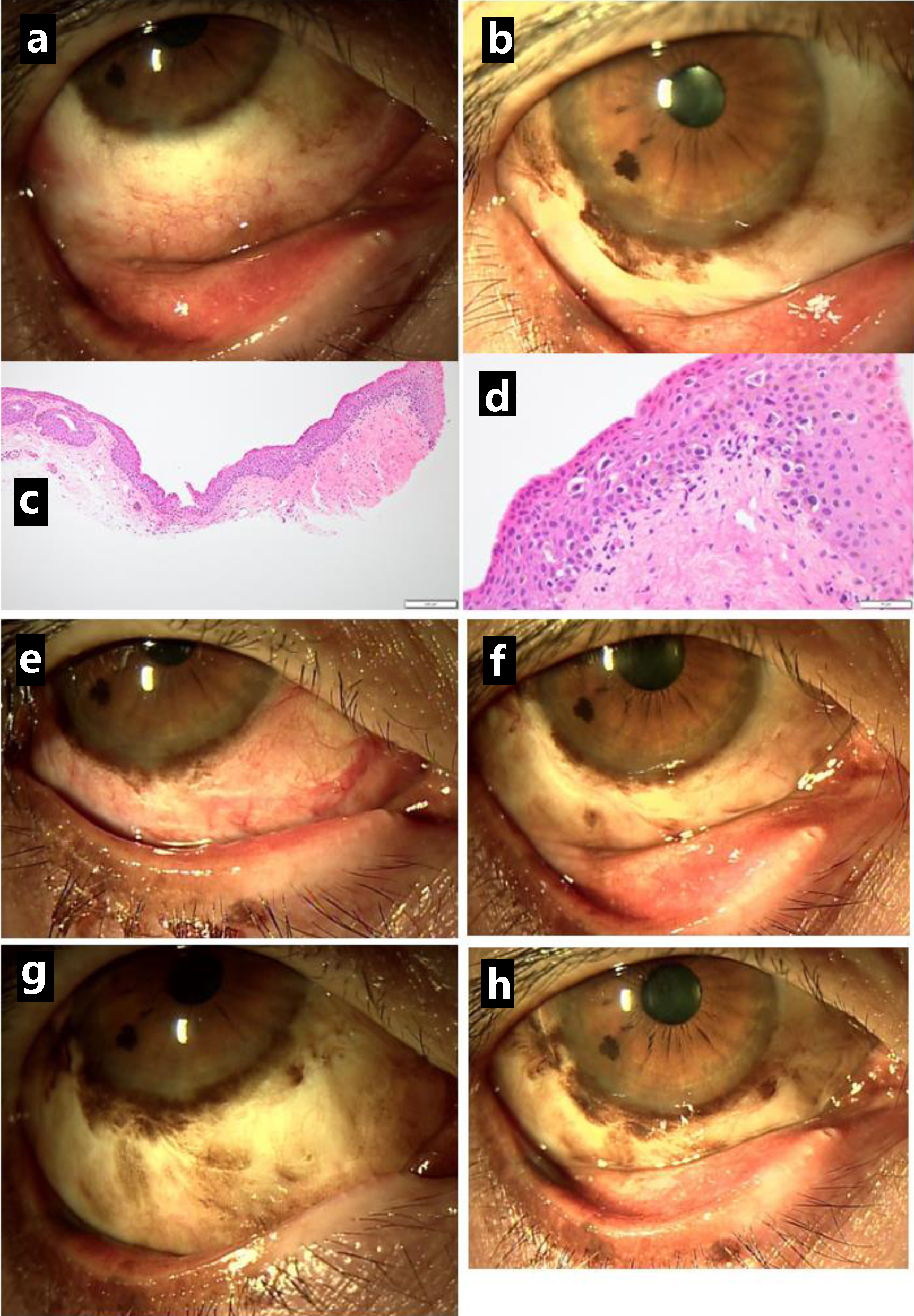

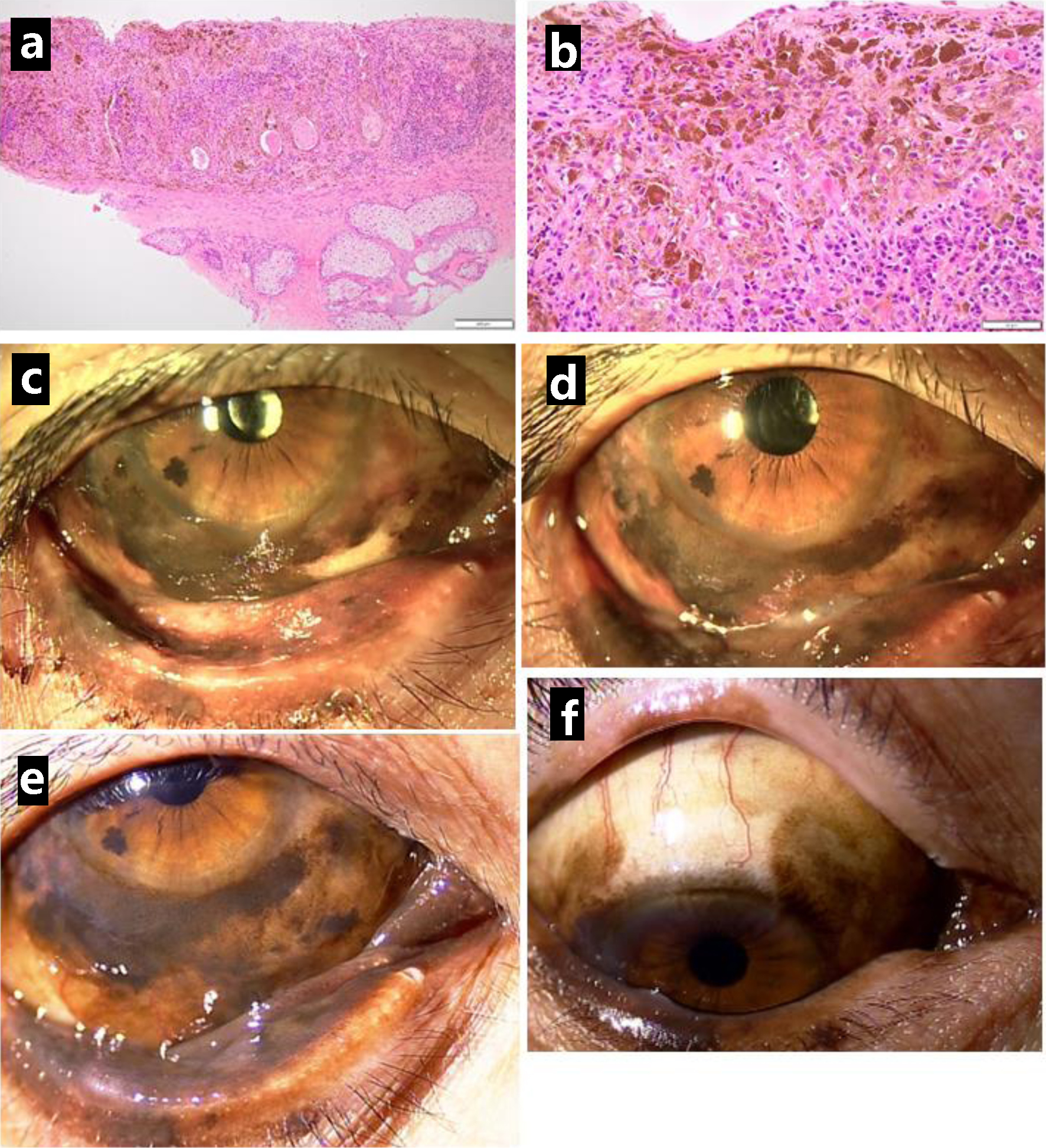

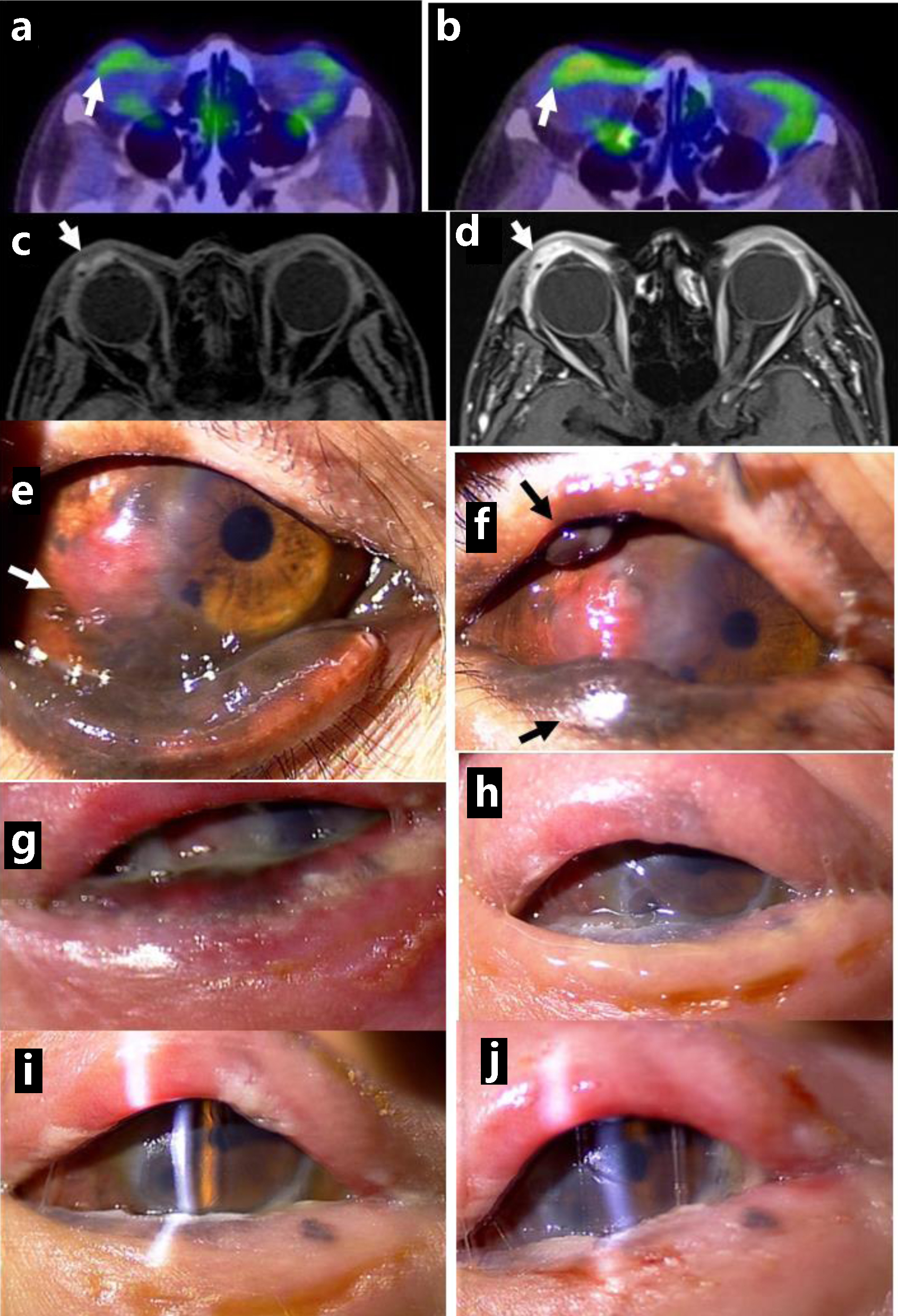

She was well (Fig. 3a) until the age of 66 years, 10 months later from the initial visit, when she showed pigmented lesions along the lower corneal margin (Fig. 3b). She underwent the third resection of the bulbar conjunctiva in the right eye, showing malignant melanoma in situ (Fig. 3c, d). The bulbar conjunctival pigmented lesion in the right eye gradually relapsed and spread at a slow pace in a year (Fig. 3e-h). At the age of 67 years, 2 years from the initial visit, she underwent cataract surgery with intraocular lens implantation in both eyes. At the age of 68 years, 2.5 years from the initial visit, she showed marked proliferation of the bulbar conjunctival pigmented lesion in the previous 1 year (Fig. 4c), and thus, underwent resection of the lower eyelid-edge lesion in the right eye for a genomic DNA-based test of BRAF mutations (V600E and V600K) which turned out to be absent. The pathological examination showed melanoma in situ (Fig. 4a, b). Based on this result, she started to have intravenous nivolumab 240 mg every 3 weeks, instead of the standard interval of every 2 weeks since she visited the hospital at long distance. She also began to have entecavir 0.5 mg daily toward HBV. She showed iritis with mutton-fat keratic precipitates in the right eye 3 months after the beginning of nivolumab and used 0.1% betamethasone eye drops four times daily to control the intraocular inflammation. The conjunctival pigmented lesions were basically stable but were slow in progress (Fig. 4d-f) until 2 years later, 5 years from the initial visit, when a non-pigmented nodular lesion (Fig. 5e) developed on the temporal side of the bulbar conjunctiva along the corneal limbus in the right eye. [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed no abnormal uptake systemically, except for slightly higher uptake with maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) less than 2.0 (Fig. 5b) in the surface area of the right eye globe, compared with 5 years previously (Fig. 5a). Further 3 months later, pigmented tumorous lesions developed near the edge of upper and lower eyelid (Fig. 5f). The visual acuity in the right eye dropped to 0.06 from 0.6 in those 3 months due to corneal deformation by the non-pigmented nodular lesion on the bulbar conjunctiva. Magnetic resonance imaging showed the ocular surface saucer-like lesion without deep orbital infiltration on the right side which was enhanced in the arterial phase (Fig. 5c, d).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Clear lower bulbar conjunctiva (a) in the right eye one month after the resection but pigmented lesions along the corneal limbus (b) relapsing in half a year. The excision of relapsed lesion showing conjunctival malignant melanoma in situ (c in low magnification, d in high magnification). Relatively clear lower bulbar conjunctiva just after the excision (e) and one month later (f), 1 year from the initial visit. The pigmented lesions gradually increase half a year after the excision (g) and 1 year later (h), 2 years from the initial visit. Scale bar = 200 µm in c, 50 µm in d. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Resection of lower eyelid-edge pigmented lesion in the right eye, 2.5 years after the initial visit, showing malignant melanoma in situ (a in low magnification, b in high magnification). Photos just before the resection (c) and 1 year later (d), 3.5 years from the initial visit. Pigmented lesions spreading to the lower palpebral conjunctiva (e) and upper bulbar conjunctiva (f) half a year later, 4 years from the initial visit. Scale bar = 200 µm in a, 50 µm in b. |

Click for large image | Figure 5. Positron emission tomography, showing no abnormal uptake in ocular surface of the right eye at the initial visit (arrow, a) and mildly increased uptake 5 years from the initial visit (arrow, b). Magnetic resonance imaging with enhancement, showing saucer-like ocular surface lesion on the right side (arrow, c) with marked enhancement in arterial phase (arrow, d), 5.5 years from the initial visit. Non-pigmented nodular lesion on the temporal bulbar conjunctiva along the corneal limbus (arrow, e), 5 years from the initial visit, and pigmented nodular lesions in the upper and lower eyelids (arrows, f). 3 months later. No pigmented lesion in the eyelids and ocular surface immediately after the completion of proton beam therapy (g), 1 month later (h), 3 months later (i), and 5 months later (j). Note clear cornea with slit-lamp examination (i, j). |

At this time point, she was immediately recommended to undergo proton beam therapy for the local control of malignant melanoma. She underwent proton beam therapy at the total dose of 70.4 Gy, as relative biological effectiveness, at 32 fractions in one and a half months. She continued to have intravenous nivolumab at the increased dose of 480 mg every 4 weeks, after proton beam therapy. Serum HBV-DNA became negative with continuous administration of entecavir. She only used 0.1% hyaluronan eye drops four times daily in the right eye. The visual acuity in the right eye was hand movement 1 month after the completion of proton beam therapy and was elevated to 0.03 two months after the therapy. She became free of pigmented lesions on the ocular surface, upper and lower eyelids (Fig. 5g, h) on the right side and maintained the transparent cornea in the right eye in half a year until the latest follow-up (Fig. 5i, j).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This patient presented two clinical signs of suspected conjunctival melanoma and a hepatic mass lesion in the background of an HBV carrier. The hepatic mass was diagnosed as HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma via needle liver biopsy by a hepatologist, and evaluated further by computed tomography during hepatic arteriography and arterial portography to proceed to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of the mass. In parallel, excisional biopsy of the conjunctival lower fornical pigmented lesion was made by an ophthalmologist to prove malignant melanoma in situ. As a priority, she underwent segmental liver resection after the presurgical transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of the mass. The conjunctival melanoma was followed with no systemic treatment by an ophthalmologist and a dermatologist since she had no metastatic lesion revealed by positron emission tomography. She repeatedly underwent local resection of the conjunctival lesions, leading to the diagnosis of conjunctival melanoma in situ, twice in a year from the initial diagnosis.

About 2.5 years from the initial diagnosis of conjunctival melanoma in situ, the lower eyelid-edge lesion in the right eye was resected to show in situ melanoma and to check BRAF mutations in genomic DNA of the tumor to consider for molecular targeted therapy [16]. Since the BRAF mutations were absent, she began to have an intravenous immune checkpoint inhibitor, anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1), nivolumab. She developed iritis in the right eye with conjunctival melanoma as an immune-related adverse event, 3 months after the beginning of PD-1 inhibitor, nivolumab. Nivolumab is known to cause Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease-like signs and symptoms in both eyes [17], whilst this patient only showed iritis in the unilateral eye with conjunctival melanoma and did not develop iris nodules and depigmented ocular fundus. The iritis was well controlled by daily topical 0.1% betamethasone eye drops for the following 2 years.

Since the diagnosis of conjunctival melanoma in situ, local therapies such as cryotherapy and topical chemotherapy had been repeatedly discussed with the patient and her husband. As the patient had good vision in the right eye with no symptoms, we reached the conclusion to wait and see the timing of increased malignancy to initiate the radiotherapy in shared decision-making. The clinical phase of conjunctival melanoma appeared to be drastically changed 5 years from the initial diagnosis when she developed a nodular non-pigmented lesion, indicative of increased malignancy of melanoma. In a few months, she also developed the other nodular pigmented lesions in the upper and lower eyelids. Proton beam therapy was planned in a hurry while intravenous nivolumab was continued. The condition of proton beam therapy was the same as that described previously for giant ocular surface conjunctival melanoma [7]. Based on our previous experience, corneal melt and perforation was expected to occur in a relatively early phase after the proton beam therapy [7]. Fortunately, the present patient maintained the corneal integrity in half a year after the completion of proton beam therapy. The reason for the maintenance of corneal transparency in the present patient remained unknown but might be attributed to her younger age, compared with the previous older patient who showed the corneal melt. The patient, thus, achieved the local control of conjunctival melanoma by proton beam therapy and avoided orbital exenteration, according to her wish.

Conclusions

The woman, as an HBV carrier, presented concurrently a liver mass and bulbar conjunctival pigmented lesions in the right eye. Needle liver biopsy and excisional conjunctival biopsy showed hepatocellular carcinoma and conjunctival malignant melanoma in situ, respectively. The priority was given to segmental liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. She showed no metastasis in 6 years of follow-up, but later in the course, developed abrupt nodular growth of conjunctival melanoma. She, at this moment, underwent proton beam therapy toward the conjunctival melanoma to obtain successful local control. Multidisciplinary team of different specialties in ophthalmology, dermatology, radiology, hepatology, and pathology talked to one another and chose the best possible way for treatment strategy since the evidence for standard care is lacking in such a rare disease as conjunctival melanoma.

Learning points

The management of conjunctival melanoma is difficult and still challenging, without recognized standard of care at moment. A better outcome of treatment with the preservation of the ocular globe was achieved by proton bean therapy in a patient with conjunctival melanoma. In general, treatment for head and neck cancer, including conjunctival melanoma, should be considered from both cosmetic and functional points of view. Proton beam therapy is a treatment option to fit with the purpose of cosmetic and functional maintenance in a rare disease like conjunctival malignant melanoma.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The authors receive no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for her anonymized information to be published in this article. Ethics committee review was not applicable to case reports, based on the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, issued by the Government of Japan.

Author Contributions

TM, as an ophthalmologist, and KT and OY, as dermatologists, followed and treated the patient, TT, as a pathologist, made the pathological diagnosis, and TO and TW, as radiologists, TF, as a gastroenterological surgeon, TA, as a hepatologist, treated the patient. TM wrote the manuscript, and TO, TW, TT, KT, TF, TA, and OY did critical review of the manuscript, and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Lopez F, Rodrigo JP, Cardesa A, Triantafyllou A, Devaney KO, Mendenhall WM, Haigentz M, Jr., et al. Update on primary head and neck mucosal melanoma. Head Neck. 2016;38(1):147-155.

doi pubmed - Grant-Freemantle MC, Lane O'Neill B, Clover AJP. The effectiveness of radiotherapy in the treatment of head and neck mucosal melanoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):323-333.

doi pubmed - Gilain L, Houette A, Montalban A, Mom T, Saroul N. Mucosal melanoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2014;131(6):365-369.

doi pubmed - Seregard S. Conjunctival melanoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42(4):321-350.

doi pubmed - Vora GK, Demirci H, Marr B, Mruthyunjaya P. Advances in the management of conjunctival melanoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2017;62(1):26-42.

doi pubmed - Jain P, Finger PT, Fili M, Damato B, Coupland SE, Heimann H, Kenawy N, et al. Conjunctival melanoma treatment outcomes in 288 patients: a multicenter international data-sharing study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105:1358-1364.

doi pubmed - Matsuo T, Yamasaki O, Tanaka T, Katsui K, Waki T. Proton beam therapy followed by pembrolizumab for giant ocular surface conjunctival malignant melanoma: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2022;16(1):12.

doi pubmed - Matsuo T, Tanaka T, Yamasaki O. Lacrimal sac malignant melanoma in 15 Japanese patients: case report and literature review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2019;7:2324709619888052.

doi pubmed - Matsuo T, Ogino Y, Ichimura K, Tanaka T, Kaji M. Clinicopathological correlation for the role of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography computed tomography in detection of choroidal malignant melanoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2014;19(2):230-239.

doi pubmed - Wuestemeyer H, Sauerwein W, Meller D, Chauvel P, Schueler A, Steuhl KP, Bornfeld N, et al. Proton radiotherapy as an alternative to exenteration in the management of extended conjunctival melanoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244(4):438-446.

doi pubmed - Maschi-Cayla C, Doyen J, Gastaud P, Caujolle JP. Conjunctival melanomas and proton beam therapy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91(8):e647.

doi pubmed - Scholz SL, Herault J, Stang A, Griewank KG, Meller D, Thariat J, Steuhl KP, et al. Proton radiotherapy in advanced malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;257(6):1309-1318.

doi pubmed - Thariat J, Salleron J, Maschi C, Fevrier E, Lassalle S, Gastaud L, Baillif S, et al. Oncologic and visual outcomes after postoperative proton therapy of localized conjunctival melanomas. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14(1):239.

doi pubmed - Spatola C, Liardo RLE, Milazzotto R, Raffaele L, Salamone V, Basile A, Foti PV, et al. Radiotherapy of conjunctival melanoma: role and challenges of brachytherapy, photon-beam and protontherapy. Appl Sci. 2020;10:9071.

- Butt K, Hussain R, Coupland SE, Krishna Y. Conjunctival melanoma: a clinical review and update. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(18):3121.

doi pubmed - Larsen AC, Dahmcke CM, Dahl C, Siersma VD, Toft PB, Coupland SE, Prause JU, et al. A retrospective review of conjunctival melanoma presentation, treatment, and outcome and an investigation of features associated with BRAF mutations. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(11):1295-1303.

doi pubmed - Matsuo T, Yamasaki O. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease-like posterior uveitis in the course of nivolumab (anti-PD-1 antibody), interposed by vemurafenib (BRAF inhibitor), for metastatic cutaneous malignant melanoma. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(5):694-700.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.