| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 2, February 2025, pages 69-76

An Adverse Double-Hit by Pembrolizumab: A Case Report of Bullous Pemphigoid and Pneumonitis

Christodoulos Chatzigrigoriadisa, h , Prodromos Avramidisa

, Christos Davoulosb

, Foteinos-Ioannis Dimitrakopoulosc

, George Eleftherakisb

, Christina Petropouloub

, Despoina Sperdoulid

, Georgios Marios Stergiopoulose

, Panagis Galiatsatosf

, Stelios Assimakopoulosg

aSchool of Medicine, University of Patras, Patras, Greece

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, University General Hospital of Patras, 26504 Rio, Greece

cDepartment of Oncology, Medical School, University of Patras, 26504 Patras, Greece

dSchool of Medicine, National Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

eDepartment of Molecular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55905, USA

fDepartment of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA

gDivision of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Patras Medical School, Patras, Greece

hCorresponding Author: Christodoulos Chatzigrigoriadis, School of Medicine, University of Patras, Patras, Greece

Manuscript submitted November 28, 2024, accepted January 24, 2025, published online February 2, 2025

Short title: A Case of Pembrolizumab and Autoimmunity

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5089

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Immune checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab represent a modern approach to the management of various malignancies, including non-small cell lung cancer. The therapeutic activity of immunotherapy is exerted by the activation of immune cells against the tumor cells. However, systemic activation of the immune system can lead to the development of autoimmune complications known as immune-related adverse events. A combination of rare immune-related adverse events is occasionally observed simultaneously in the same patient. We present the case of a 66-year-old male with squamous non-small cell lung carcinoma who presented to the emergency department with dyspnea and respiratory failure. Imaging findings were consistent with pulmonary embolism and nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis. One month before this event, he was diagnosed with bullous pemphigoid following 21 cycles of treatment with pembrolizumab. The radiological findings, the lack of response to antibiotics, the negative microbiological workup, and the excellent response to corticosteroids established the diagnosis of pembrolizumab-induced pneumonitis. The combination of bullous pemphigoid and pneumonitis secondary to pembrolizumab is rare; only a few case reports exist in the literature. Hence, this case highlights the possibility of multiple immune-related adverse events in the same patient. The exclusion of infectious diseases and other immunologic disorders with a similar clinical presentation is necessary to make the final diagnosis of immune-related adverse events and start the appropriate treatment. Serology, histopathology, and direct immunofluorescence aid to the diagnosis of immune-related bullous pemphigoid; the differential diagnosis includes other pemphigoid or lichenoid diseases, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Imaging, microbiological testing, and bronchoscopy (if possible) confirm the diagnosis of immune-related pneumonitis, which should be differentiated from acute coronary syndrome, cardiogenic pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolism, tumor progression, and lower respiratory tract infections (especially Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in immunocompromised patients). An interdisciplinary approach is necessary for the management of these cases.

Keywords: Pembrolizumab; Immunotherapy; Immune checkpoint inhibitor; Immune-related adverse event; Pneumonitis; Bullous pemphigoid; Autoimmunity; Non-small cell lung cancer

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Pembrolizumab is an immunotherapeutic agent that targets the programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) receptor and is widely used for the treatment of various malignancies, including head and neck cancer and non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) [1]. Tumor cells express programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) on their surface, which is thought to interact with the inhibitory PD-1 receptor on T cells [1]. Pembrolizumab promotes T-cell activation against multiple tumors [1, 2]. In general, immunotherapy is considered a safer approach compared to regular chemotherapy [2]. However, the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction is integral for self-tolerance and prevents the development of autoimmune diseases [1]. On the other hand, immune-related adverse events (irAEs) are adverse drug reactions in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [1-4]. The concurrent manifestation of different irAEs in the same patient is rarely reported [3]. Thus, rapid recognition of concurrent irAEs allows rapid discontinuation of immunotherapy and potential administration of immunosuppressants, e.g., corticosteroids, to avoid serious complications and achieve faster recovery. Afterwards, the oncologic outcome depends on the decision for the re-administration of immunotherapy which is guided by the resolution of irAEs. Herein, we present the case of a 66-year-old man diagnosed with head and neck cancer as well as squamous non-small cell lung cancer, who was treated with pembrolizumab for an extended period. This patient was diagnosed with bullous pemphigoid (BP) after 21 cycles of treatment with pembrolizumab, followed by immunotherapy-induced pneumonitis and pulmonary embolism (PE) 1 month later. Diagnosing this rare combination of irAEs emphasizes the importance of vigilance in patients treated with ICIs [1-3].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Our patient is a 66-year-old man with a past medical history of heavy smoking history (35 pack-years) and increased alcohol consumption. The patient had been diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue (2012), for which he received radiotherapy combined with cisplatin chemotherapy followed by six cycles of chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil.

During the regular follow-up, in March 2023, a new lesion in the right upper lobe was detected. Transbronchial needle aspiration confirmed the existence of a secondary primary malignancy, squamous NSCLC. The tumor was deemed unresectable and based on the molecular profile (PD-L1: 1-2%), first-line treatment with pembrolizumab was given. The patient continued with the same treatment (a total of 21 cycles, beginning in April 2023 and continuing until August 2024) with no radiological signs of tumor progression.

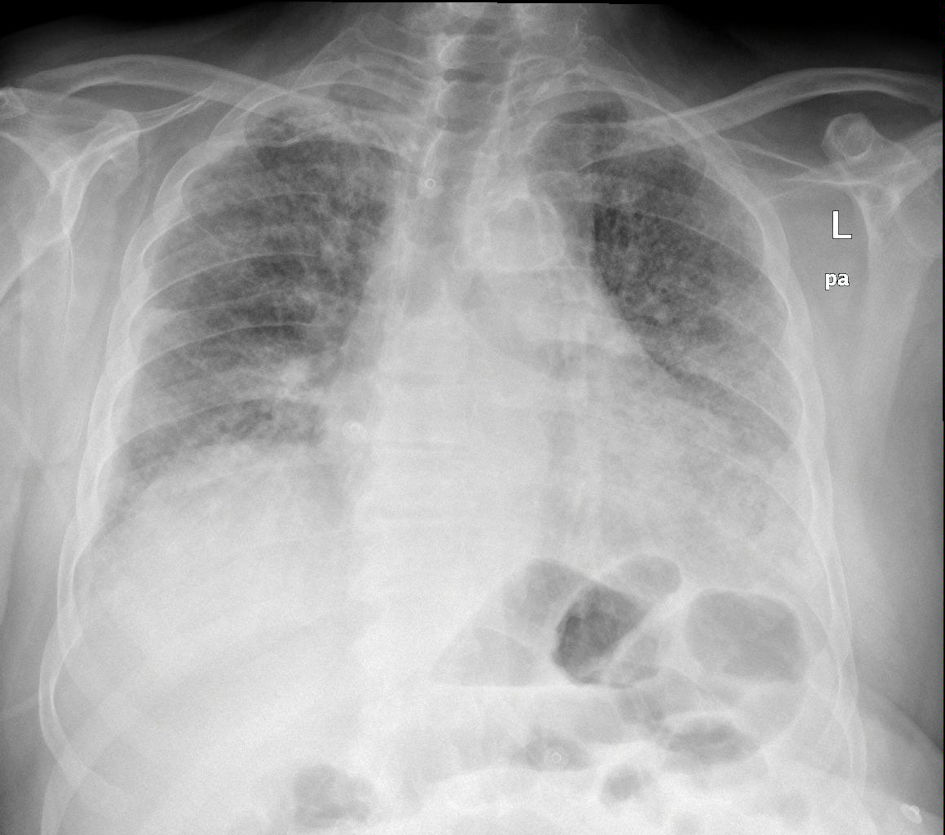

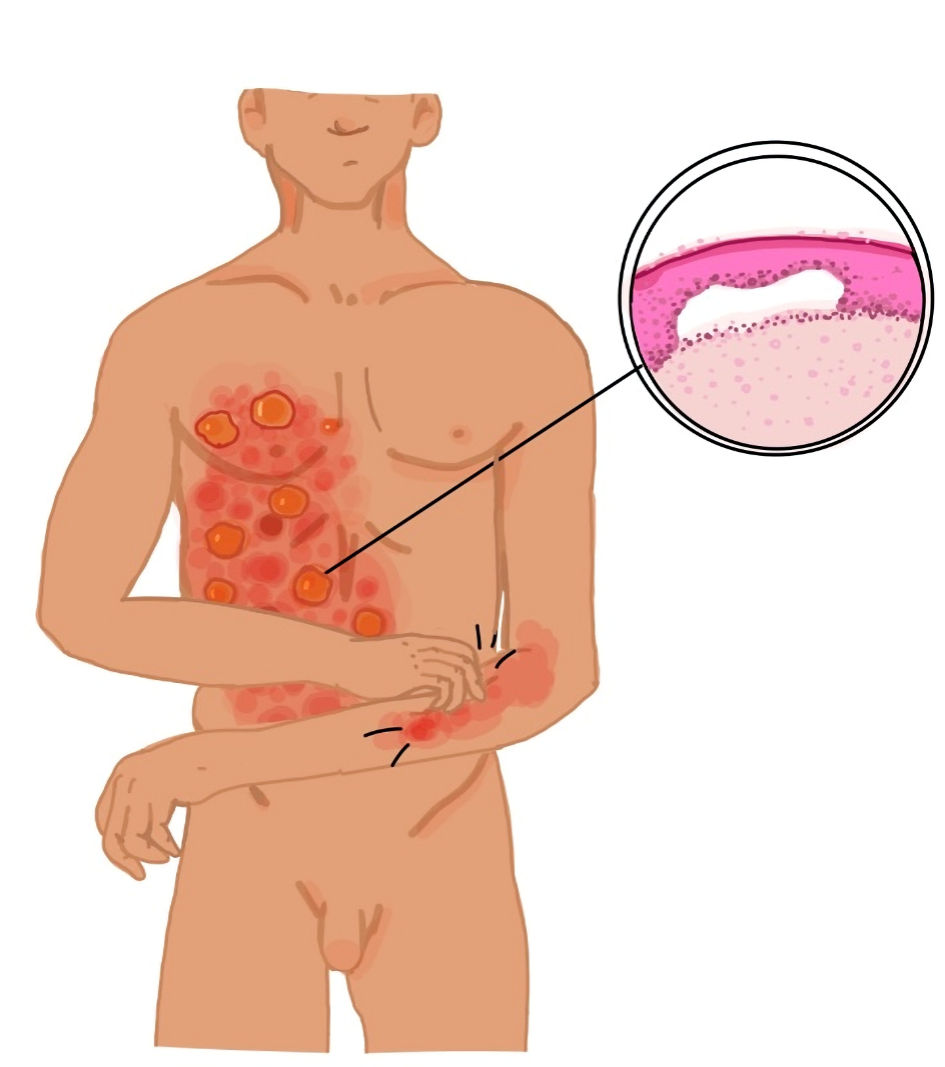

A few days after the 21st cycle, the patient developed an erythematous and pruritic rash with erosions and blistering in his chest, abdomen, back, and extremities, covering approximately 10% of his body surface area (BSA) (Fig. 1). Treatment with topical clobetasol 0.05% twice a day and per os bilastine 20 mg by his primary care physician provided symptomatic relief and improvement of the rash. Furthermore, a skin biopsy revealed a subepidermal blister with neutrophils and numerous eosinophils. Focal eosinophilic spongiosis was observed in the epidermis around the vesicle. Additionally, there was chronic inflammatory infiltrate with perivascular predominance and numerous eosinophils in the dermis, leading to the diagnosis of BP.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Tense bulla with clear fluid on the right upper extremity of the patient. Note the erythematous rash with erosions and blistering. |

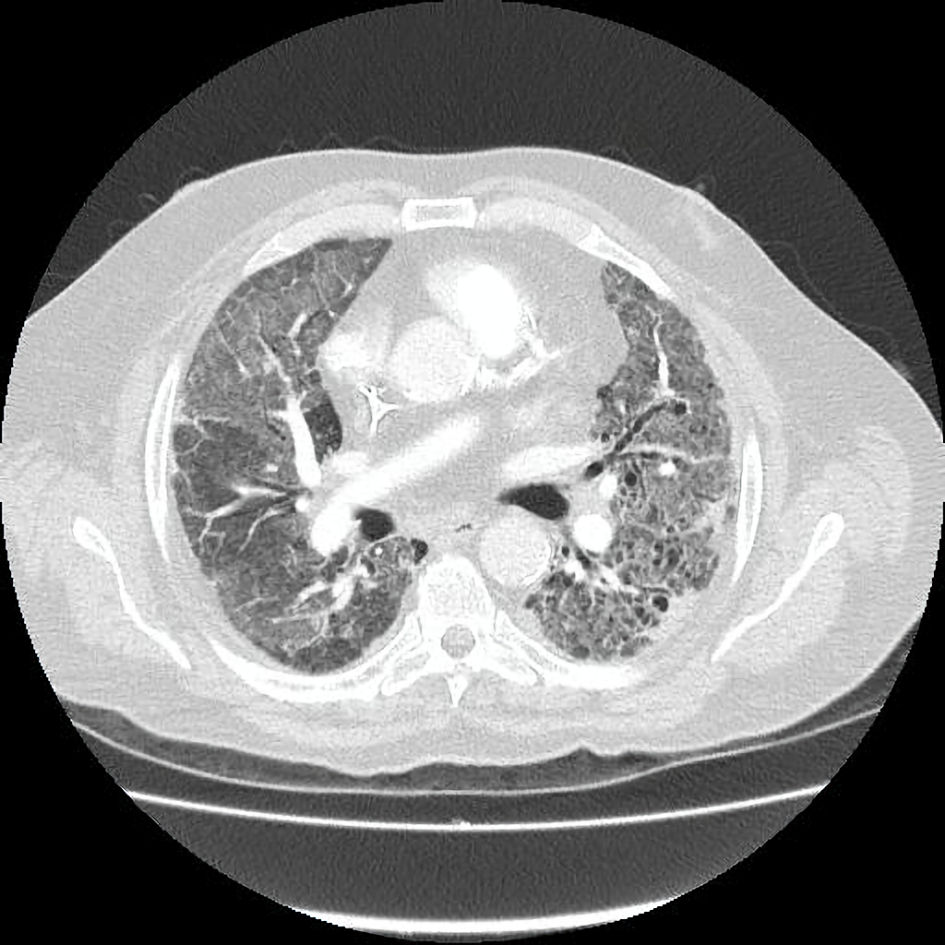

One month later, the patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with new-onset dyspnea, fatigue, and hypoxemia (oxygen saturation 75% in room air), so high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) 60/85 was applied. The physical examination was nonspecific except for crackles and expiratory wheezing. The initial diagnostic workup was notable for elevated cardiac enzymes and inflammatory markers (Table 1). Chest X-ray (CXR) revealed bilateral interstitial infiltrates, and chest computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) suggested PE (Fig. 2). The chest CTPA also revealed enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, bilateral and symmetric honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and ground glass opacities (Fig. 3). Consequently, the patient was admitted to the hospital and was treated with subcutaneous (SC) fondaparinux 7.5 mg once a day and intravenous (IV) antibiotic regimens including piperacillin/tazobactam-moxifloxacin and then linezolid-meropenem without improvement. At this point, a thorough diagnostic approach was performed, which included blood cultures, pneumococcal antigen test, legionella antigen test, serum galactomannan antigen test, and multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for respiratory viruses and atypical bacteria (Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae), which were all negative. The interstitial infiltrates on CXR, the CT findings of nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis, and the history of pembrolizumab treatment suggested pembrolizumab-induced pneumonitis. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) was still included in our differential diagnosis; however, the decision to avoid the bronchoscopy for diagnostic purposes was taken due to unfavorable oxygenation status. Empiric treatment with IV methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg, IV trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 400/80 mg four times a day, IV omeprazole, and SC fondaparinux was initiated after discontinuing antibacterial agents. TMP-SMX was discontinued due to hyperkalemia and was replaced by atovaquone. HFNO was de-escalated to Venturi mask (VM) 50% 5 days later. Seven days later, the dose of IV methylprednisolone was de-escalated to 1 mg/kg and VM 35% for the last 2 days of inpatient treatment. The laboratory values were slowly normalized, and the rash of BP completely resolved with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Eventually, the patient was discharged with a nasal cannula oxygen flow of 3 L/min, oral apixaban 2.5 mg twice a day, and slow tapering of the corticosteroids for the next 30 days in addition to the previous drug regimen. Treatment with corticosteroids was combined with oral omeprazole 20 mg/day for peptic ulcer disease prevention and oral atovaquone 1,500 mg/day for PCP prophylaxis.

Click to view | Table 1. The Vital Signs and the Laboratory Values of the Initial Diagnostic Workup in the ED |

Click for large image | Figure 2. The chest X-ray showed a nonspecific pattern of bilateral interstitial infiltrates. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Chest CTPA reveals the presence of honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and ground glass opacities suggestive of nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis. CTPA: computed tomography pulmonary angiogram. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

BP is the most common immunobullous disorder caused by pembrolizumab [1, 5]. It represents a rare cutaneous irAE with an estimated incidence of 1% [4]. The typical presentation is an elderly patient treated for NSCLC or melanoma with pembrolizumab [2, 5]. The onset is variable, ranging from 2 weeks to 28 months, with a median onset of 4 months [1, 4-6]. In our patient, symptoms appeared 16 months after the first dose of pembrolizumab. The clinical presentation includes pruritus and a nonspecific urticarial or maculopapular rash followed by the appearance of characteristic bullae in the trunk and extremities [1, 4-6]. BP represents a type II hypersensitivity reaction; autoantibodies against hemidesmosome proteins, such as BP180 and BP230, separate the epidermis from the underlying basement membrane (BM) [1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8]. The mechanism of pembrolizumab-induced BP remains unclear, with T cells, B cells, and cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ hypothesized to play a role [4, 6-8]. Furthermore, BP180 and BP230 antigens are present in the normal epidermis and tumors (e.g., melanoma, NSCLC); therefore, cross-reaction of the immune system is possible [4]. The initial suspicion is based on clinical findings, eosinophilia, and positive anti-BP180/and-BP230 serology with the gold standard for diagnosis being skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence (DIF) [1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8]. Subepidermal blistering with an inflammatory infiltrate of eosinophilic predominance, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, along with linear immunoglobulin (Ig)G/C3 deposition in the BM, are typical findings [2, 4, 5, 6, 8]. Although there is limited evidence regarding optimal management, the next steps depend on the severity of the rash and tumor response to pembrolizumab (Table 2) [5, 7-10]. Our patient developed grade 1 pembrolizumab-induced BP, indicating the need for symptomatic management with H1 antagonists and topical corticosteroids without discontinuation of pembrolizumab [7-10] (Fig. 4).

Click to view | Table 2. Treatment of Bullous Pemphigoid (BP) Secondary to Immunotherapy Depending on the Severity of the Rash |

Click for large image | Figure 4. The clinical presentation and the histopathology of bullous pemphigoid. |

The differential diagnosis of the skin eruption in this patient can be challenging. Secondary BP is difficult to distinguish from idiopathic BP, given the similar clinical and histopathological features; the history of recent pembrolizumab treatment is crucial [1, 2, 8]. Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) was excluded due to the presence of pruritus and bullae, the absence of mucosal involvement, the absence of the Nikolsky sign, and the absence of intraepidermal acantholysis. Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) was excluded by the absence of oral lesions and scarring, which are typically required for the diagnosis, as histopathology and serology results are similar [11]. Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PP) was excluded due to the good response to corticosteroids, the absence of oral involvement, and the absence of acantholysis [3]. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) was excluded by the delayed presentation and the absence of flu-like prodromal illness, mucosal involvement, skin tenderness, Nikolsky sign, targetoid lesions, and epidermal-dermal separation [4, 8, 12]. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) was excluded by the absence of maculopapular rash, eosinophilia, fever, lymphadenopathy, and internal organ involvement, as well as the appearance of rash 2 - 6 weeks after drug exposure [8]. Lichen planus (LP), lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP), and bullous lichen planus (BLP) were excluded by the absence of purple papules and plaques with Wickham striae on skin examination, the absence of oral lesions, and the absence of hypergranulosis and inflammatory infiltrate (lymphocytes and histiocytes) at dermo-epidermal junction [3, 4, 8, 13].

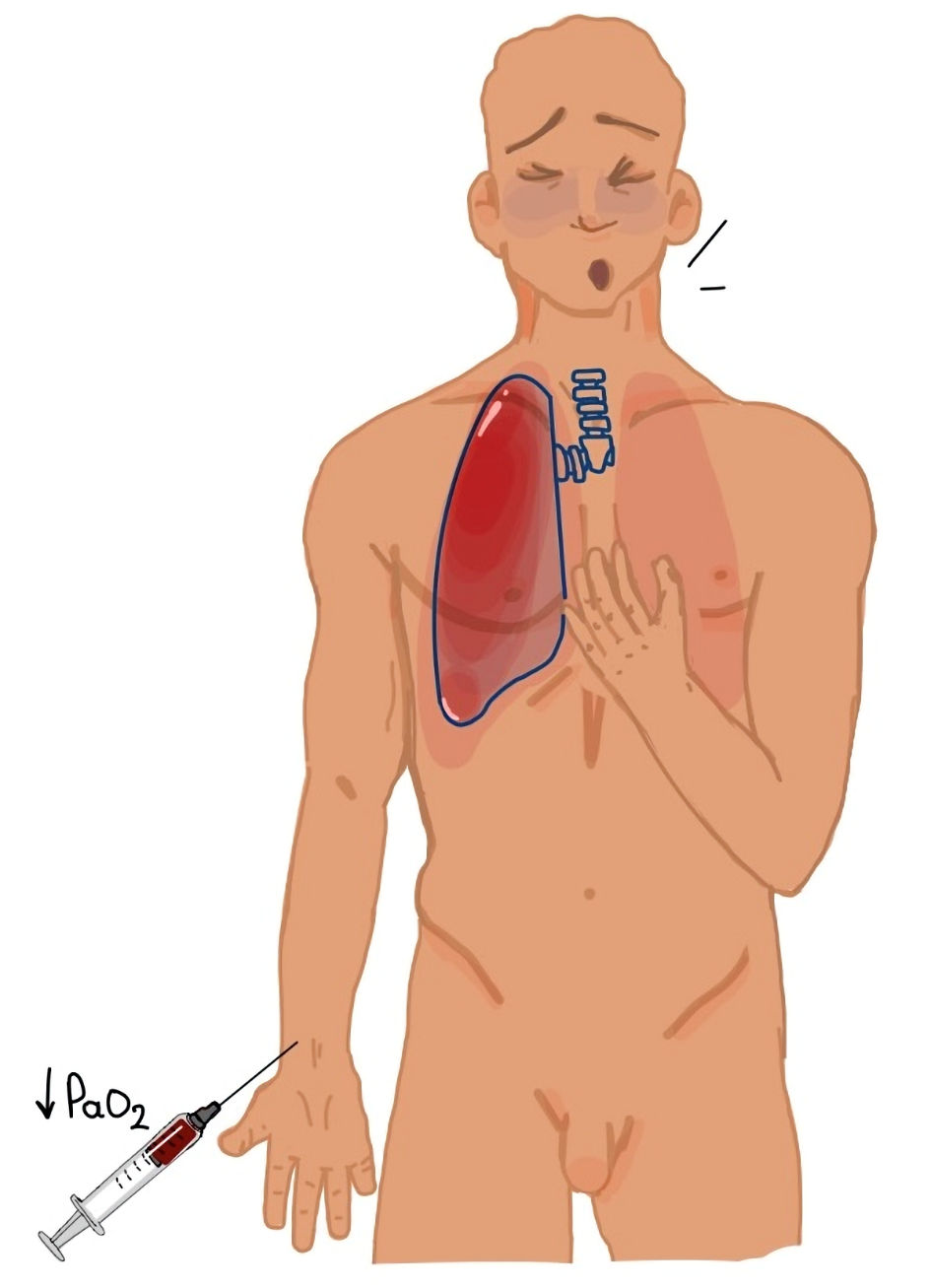

Pembrolizumab-induced pneumonitis is a rare irAE (2-5% incidence) that manifests as a focal or diffuse inflammatory interstitial lung disease (ILD) [14-18]. However, pneumonitis is one of the most common serious irAEs, with an admission rate of 60% [14]. Potential risk factors include autoimmunity, infectious diseases, radiation therapy, chest surgery, chemotherapy, aging, pleurodesis, pre-existing lung disease, specific cancer types, tumor burden, African American race, lower socioeconomic status, and smoking [17, 19-23]. The onset of pneumonitis post-pembrolizumab initiation is variable; it ranges from a few weeks to several months, with a median onset of 3 months [18, 19]. In our case, the first symptoms of pneumonitis appeared 17 months after the first cycle of ICI therapy. The clinical presentation includes dyspnea, cough, and hypoxemia [17]. Our patient presented with dyspnea and hypoxemia requiring inpatient care without mechanical ventilation, which corresponds to grade 3 pneumonitis [14] (Table 3). Currently, the pathogenesis is unclear. ICI-pneumonitis is a diagnosis of exclusion based on imaging and microbiological tests [14]. It can be classified as organizing pneumonia, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), hypersensitivity pneumonitis, or diffuse alveolar damage [14]. In our case, radiological findings were consistent with NSIP. Bronchoscopy, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid culture, and respiratory virus panel are typically required to exclude infectious diseases [14]. However, bronchoscopy is not performed in many patients, including ours, due to unfavorable respiratory parameters [14]. It has been proposed that bronchoscopy should not delay the treatment and is unnecessary in patients with classic imaging findings like in this case [17, 18]. The first-line treatment involves discontinuing pembrolizumab and initiating corticosteroids (1 - 2 mg/kg/day prednisone with a taper), as was our approach in this case [17, 18]. Furthermore, gastrointestinal prophylaxis (either proton pump inhibitor or H2 receptor antagonist) and antibiotic prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii during the treatment with corticosteroids are recommended [14]. Steroid refractory cases are rare and require alternative immunosuppressive agents, such as infliximab, mycophenolate mofetil, and tocilizumab [14, 18] (Fig. 5).

Click to view | Table 3. Management of Pneumonitis Secondary to Immunotherapy Depending on the Severity |

Click for large image | Figure 5. The clinical presentation of pneumonitis. |

The differential diagnosis of pneumonitis can be broad. Acute coronary syndrome was excluded by a normal electrocardiogram, imaging studies consistent with interstitial lung disease, and the absence of chest pain. In our patient, elevated troponin levels were attributable to hypoxemia and right ventricular strain, which were normalized after the resolution of pneumonitis. Congestive heart failure was ruled out by the absence of signs of volume overload like jugular vein distention, ankle edema, and hypertension [17, 23]. Although PE was present in this case, the infiltrates on imaging, the persistence of hypoxemia despite anticoagulation therapy, and the clinical improvement following the administration of corticosteroids indicate that PE cannot satisfactorily explain the clinical presentation of our patient [17]. An alternative diagnosis could be the progression of the underlying NSCLC due to mass effect, i.e., bronchial obstruction or lymphangitis carcinomatosis. This was ruled out by imaging studies in this case [17, 24]. The diagnostic challenge of our case was ruling out lower respiratory tract infection, which was supported by the imaging findings of interstitial lung disease, the unsuccessful trial of antibiotics, and the successful treatment with corticosteroids in combination with negative microbiological testing [17, 18, 23]. Typically, a bronchoscopy is required to rule out infectious diseases, but in real clinical practice, this is often impractical due to hypoxemia and unnecessary, like in our case [14, 17, 18]. Although PCP cannot be completely excluded from the differential diagnosis, the classic radiological findings of pneumonitis and the absence of severe immunosuppression made it less likely.

Coexistence of severe irAEs is uncommon, and the combination of BP and pneumonitis secondary to pembrolizumab is scarce, with delayed presentation reported in all cases [1-3] (Table 4). Although mucosal involvement in patients with BP is not uncommon, pulmonary involvement is extremely rare, and few reports of idiopathic BP complicated by pneumonitis exist in the literature [25-29]. Further research is necessary to understand the relationship between BP and pneumonitis, especially in patients treated with immunotherapy, with a possible explanation of the presence of a common antigen like BP180 in the skin and the lungs, or the activation of eosinophils against the cutaneous and alveolar BM [25-27]. In conclusion, a multidisciplinary approach by different specialties is essential for the proper diagnosis and treatment of irAEs, especially in those presenting with multiple irAEs, like in this case [14].

Click to view | Table 4. Reported Cases of Bullous Pemphigoid and Pneumonitis in Patients Treated With Pembrolizumab |

Learning points

ICIs like pembrolizumab inhibit the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1, causing immune system activation against the tumor cells and normal tissues. Immunotherapy is a promising therapeutic option for patients with NSCLC; however, it is often associated with the development of irAEs. irAEs are usually mild, but sometimes the clinical presentation is severe or life-threatening. This case report highlights the combination of BP and pneumonitis in a patient treated with pembrolizumab. Clinicians should be aware of the potential combination of rare irAEs. The exclusion of diseases with similar clinical presentation is required before the final diagnosis of irAEs. Serology, skin biopsy, and DIF are necessary for the diagnosis of BP. Microbiological workup, chest CT, and bronchoscopy (if possible) are necessary for the diagnosis of pneumonitis. A multidisciplinary approach is important for an individualized treatment plan. Further research is required given the limited evidence for the treatment of immunotherapy-induced BP and pneumonitis.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: CC, GE, SA. Data curation: CC, CD, FID, CP. Funding acquisition: PG. Investigation: CC, PA. Methodology: CD, FID, GE, CP, SA. Project administration: SA. Supervision: SA. Validation: FID, PG, SA. Visualization: CC, DS. Writing - original draft: CC, PA. Writing - review editing: CD, FID, CP, GMS, PG.

Date Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

PD-1: programmed cell death-1; NSCLC: non-small cell lung carcinoma; PD-L1: programmed cell death-ligand 1; irAE: immune-related adverse event; ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; BP: bullous pemphigoid; BSA: body surface area; ED: emergency department; HFNO: high-flow nasal oxygen; CXR: chest X-ray; CT: computed tomography; CTPA: computed tomography pulmonary angiogram; SC: subcutaneous; IV: intravenous; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; PCP: Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; TMP-SMX: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; VM: Venturi mask; BM: basement membrane; DIF: direct immunofluorescence; PV: pemphigus vulgaris; MMP: mucous membrane pemphigoid; PP: paraneoplastic pemphigus; SJS/TEN: Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrosis; DRESS: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; LP: lichen planus; LPP: lichen planus pemphigoides; BLP: bullous lichen planus; NSIP: nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis; BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage

| References | ▴Top |

- Correia C, Fernandes S, Soares-de-Almeida L, Filipe P. Bullous pemphigoid probably associated with pembrolizumab: a case of delayed toxicity. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61(4):e129-e131.

doi pubmed - Cardona AF, Ruiz-Patino A, Zatarain-Barron ZL, Ariza S, Ricaurte L, Rolfo C, Arrieta O. Refractory bullous pemphigoid in a patient with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma treated with pembrolizumab. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14(1):386-390.

doi pubmed - Alsabbagh M, Bava A, Ansari S. Pembrolizumab-induced hypertrophic lichenoid dermatitis and bullous pemphigoid in one patient. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023;15(3):546-548.

doi pubmed - Ellis SR, Vierra AT, Millsop JW, Lacouture ME, Kiuru M. Dermatologic toxicities to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: A review of histopathologic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1130-1143.

doi pubmed - Wang J, Hu X, Jiang W, Zhou W, Tang M, Wu C, Liu W, et al. Analysis of the clinical characteristics of pembrolizumab-induced bullous pemphigoid. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1095694.

doi pubmed - Lopez AT, Khanna T, Antonov N, Audrey-Bayan C, Geskin L. A review of bullous pemphigoid associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(6):664-669.

doi pubmed - Lomax AJ, Ge L, Anand S, McNeil C, Lowe P. Bullous pemphigoid-like reaction in a patient with metastatic melanoma receiving pembrolizumab and previously treated with ipilimumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57(4):333-335.

doi pubmed - Shalata W, Weissmann S, Itzhaki Gabay S, Sheva K, Abu Saleh O, Jama AA, Yakobson A, et al. A retrospective, single-institution experience of bullous pemphigoid as an adverse effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(21):5451.

doi pubmed - Chang ALS, Zaba L, Kwong BY. Immunotherapy for keratinocyte cancers. Part II: Identification and management of cutaneous side effects of immunotherapy treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88(6):1243-1255.

doi pubmed - Beck KM, Dong J, Geskin LJ, Beltrani VP, Phelps RG, Carvajal RD, Schwartz G, et al. Disease stabilization with pembrolizumab for metastatic acral melanoma in the setting of autoimmune bullous pemphigoid. J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:20.

doi pubmed - Lagos-Villaseca A, Koshkin VS, Kinet MJ, Rosen CA. Laryngeal mucous membrane pemphigoid as an immune-related adverse effect of pembrolizumab treatment. J Voice. 2023.

doi pubmed - Qiu C, Shevchenko A, Hsu S. Bullous pemphigoid secondary to pembrolizumab mimicking toxic epidermal necrolysis. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6(5):400-402.

doi pubmed - Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, Chelly I, El Euch D, Zitouna M, Mokni M, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(4):406-412.

doi pubmed - Brito-Dellan N, Franco-Vega MC, Ruiz JI, Lu M, Sahar H, Rajapakse P, Lin HY, et al. Optimizing inpatient care for lung cancer patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-related pneumonitis using a clinical care pathway algorithm. Support Care Cancer. 2024;32(10):661.

doi pubmed - Mavadia A, Choi S, Ismail A, Ghose A, Tan JK, Papadopoulos V, Sanchez E, et al. An overview of immune checkpoint inhibitor toxicities in bladder cancer. Toxicol Rep. 2024;13:101732.

doi pubmed - Tokito T, Kolesnik O, Sorensen J, Artac M, Quintela ML, Lee JS, Hussein M, et al. Epacadostat plus pembrolizumab versus placebo plus pembrolizumab as first-line treatment for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with high levels of programmed death-ligand 1: a randomized, double-blind phase 2 study. BMC Cancer. 2024;23(Suppl 1):1251.

doi pubmed - Brower B, McCoy A, Ahmad H, Eitman C, Bowman IA, Rembisz J, Milowsky MI. Managing potential adverse events during treatment with enfortumab vedotin + pembrolizumab in patients with advanced urothelial cancer. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1326715.

doi pubmed - Nagpal C, Rastogi S, Shamim SA, Prakash S. Re-challenge of immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab with concurrent tocilizumab after prior grade 3 pneumonitis. Ecancermedicalscience. 2023;17:1644.

doi pubmed - Haga S, Sekine A, Hagiwara E, Kaneko T, Ogura T. Early Onset of Severe Interstitial Pneumonitis Associated With Anti-PD-1 Immune Checkpoint Antibody After Pleurodesis. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e58798.

doi pubmed - Wasamoto S, Imai H, Tsuda T, Nagai Y, Kishikawa T, Ono A, Masubuchi K, et al. Efficacy and safety of first-line pembrolizumab plus platinum and pemetrexed in elderly patients with non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Intern Med. 2025;64(1):55-64.

doi pubmed - Jungbauer F, Affolter A, Brochhausen C, Lammert A, Ludwig S, Merx K, Rotter N, et al. Risk factors for immune-related adverse effects during CPI therapy in patients with head and neck malignancies - a single center study. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1287178.

doi pubmed - Rong Y, Bentley JP, Bhattacharya K, Yang Y, Chang Y, Earl S, Ramachandran S. Incidence and risk factors of immune-related adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors among older adults with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2024;13(1):e6879.

doi pubmed - Horiuchi K, Ikemura S, Sato T, Shimozaki K, Okamori S, Yamada Y, Yokoyama Y, et al. Pre-existing interstitial lung abnormalities and immune checkpoint inhibitor-related pneumonitis in solid tumors: a retrospective analysis. Oncologist. 2024;29(1):e108-e117.

doi pubmed - Umehana M, Hosono M, Hijikata Y, Takahashi M, Kanagaki M. Pembrolizumab-associated pneumonitis resembling lymphangitic carcinomatosis in a melanoma patient. Clin Nucl Med. 2023;48(11):e529-e531.

doi pubmed - Koga H, Hamada T, Ohyama B, Nakama T, Yasumoto S, Hashimoto T. An association of idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia with pemphigoid nodularis: a rare variant of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(11):1339-1340.

doi pubmed - Yoshioka D, Ishii H, Uchida T, Fujiwara S, Umeki K, Sakamoto N, Kadota JI. Interstitial pneumonia associated with bullous pemphigoid. Chest. 2012;141(3):795-797.

doi pubmed - Kariya ST, Stern RS, Schwartzstein RM, Frank H, Brown RS. Pulmonary hemorrhage associated with bullous pemphigoid of the lung. Am J Med. 1989;86(1):127-128.

doi pubmed - Klinger JR, Donat W. Pulmonary hemorrhage associated with bullous pemphigoid of the lung. Am J Med. 1989;86(5):636-637.

doi pubmed - Smith RJ, Sessions RB, Bean SF. Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1982;91(2 Pt 1):142-144.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.