| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com/ |

Case Report

Volume 15, Number 12, December 2024, pages 387-395

Exploring Overlap Syndromes: An Atypical Case of Multiple Sclerosis With Anti-Sjogren’s Syndrome Type B Antibody

Rebecca L. Shakoura, c , Oriana Tascioneb, Nathan Carberrya, Ramon Flores-Gonzaleza

aDepartment of Neurology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA

bDepartment of Neurology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

cCorresponding Author: Rebecca L. Shakour, Department of Neurology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136, USA

Manuscript submitted September 11, 2024, accepted October 21, 2024, published online October 30, 2024

Short title: An Atypical Case of MS With Anti-SSB Antibody

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc4336

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Evaluating patients with symptoms suggestive of demyelinating disease such as multiple sclerosis (MS) is common in both the inpatient and outpatient setting but may be difficult if atypical neurological symptoms are present. In this case, a 39-year-old female presented with new onset weakness and paresthesias. The patient reported 3 weeks of progressively worsening left face and hemibody numbness, along with gait abnormality. She was found to have absent lower extremity reflexes, unexpected imaging findings, and a positive anti-Sjogren’s syndrome type B (SSB) antibody despite lacking the typical sicca symptoms associated with Sjogren’s syndrome (SS). This case report underscores the diagnostic complexity of overlapping MS and SS, highlighting the need for a comprehensive differential diagnosis when atypical neurological symptoms are present. It also emphasizes the importance of considering autoimmune overlap syndromes in such cases, as the co-occurrence of these conditions can significantly impact both diagnosis and treatment strategies, requiring a multidisciplinary approach for optimal patient care.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis; Sjogren’s syndrome; Central nervous system; Peripheral nervous system; Demyelination; Rheumatologic disease

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Multiple sclerosis (MS), a common autoimmune demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS), is characterized by a wide range of neurological symptoms, including hemiparesis, monocular painful vision loss, gait ataxia, and paresthesias [1, 2]. These symptoms may overlap with other autoimmune conditions, adding complexity to the diagnosis. Among these, Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) stands out due to its diverse systemic and neurological manifestations, which can mimic those of MS [3-9]. In this case report, we present a 39-year-old female who exhibited progressive neurological symptoms initially suggestive of MS, including left-sided facial and hemibody paresthesias and gait abnormalities. However, her bilateral absence of lower extremity reflexes, as well as specific magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, pointed towards another disease involving the peripheral nervous system. Interestingly, the patient tested positive for anti-Sjogren’s syndrome B (SSB) antibody, yet she did not exhibit the classic sicca symptoms commonly associated with SS. This unexpected presentation prompted a deeper investigation into the patient’s condition, underscoring the intricacies and subtleties in diagnosing overlapping autoimmune diseases.

The majority of cases in the literature that explore the overlap syndrome of MS and SS involve patients exhibiting sicca symptoms [10-12]. Our case report highlights the need of including SS in the differential diagnosis of MS when patients present with atypical neurological findings, even if they do not exhibit the classic sicca manifestations. Furthermore, proper diagnostic workup is required to differentiate an overlapping syndrome from solely SS with CNS involvement. The management of such overlapping conditions often requires a nuanced approach, utilizing therapies effective across multiple diseases.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 39-year-old woman with no past medical history presented to the emergency department with 3 weeks of progressively worsening left face and hemibody paresthesias, as well as an abnormal gait with dragging of the left leg. She reported no visual symptoms or incontinence of either her bladder or bowel. She endorsed recent travel to Tennessee and New York within the past 3 months but denied any tick bites or illness. She denied a history of similar symptoms within her family.

Her physical examination demonstrated normal mental status and language, as well as normal cranial nerves, including unremarkable pupillary responses and absent red color desaturation. Her muscle bulk was preserved, and her tone was normal throughout her arms and legs. Her power on confrontation showed weakness in her left hip flexor, knee extensor, knee flexor, and plantar flexor. Her sensory responses were normal to all modalities, although she endorsed a subjective electrical sensation throughout the left hemibody, including the left side of her face and neck. Her reflexes were normal and symmetrical in her arms but absent in her bilateral patella and Achilles tendons. She had bilateral flexor plantar responses. Her gait demonstrated dragging of her left leg without circumduction, and she had an absent Romberg’s sign.

Diagnosis

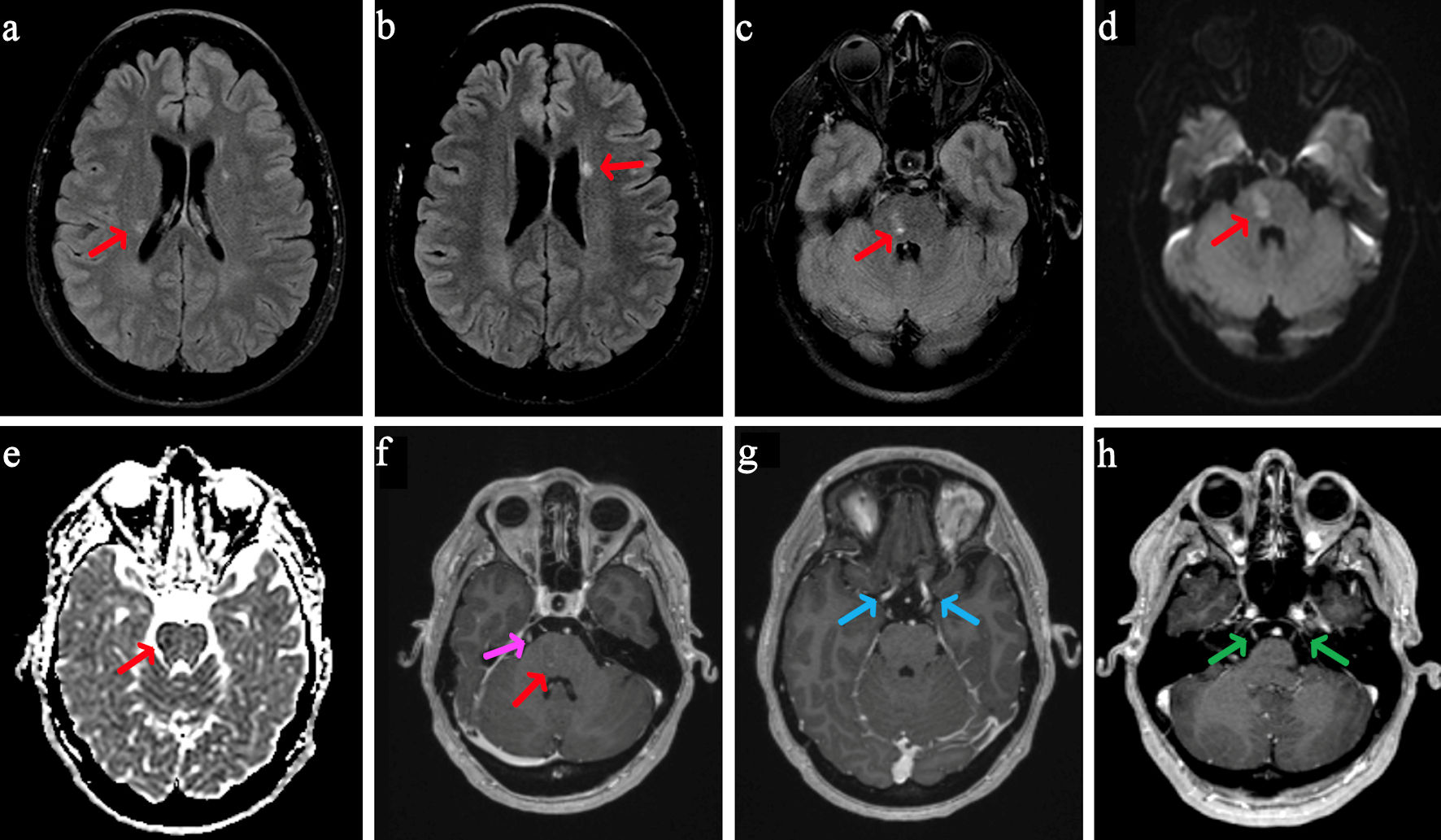

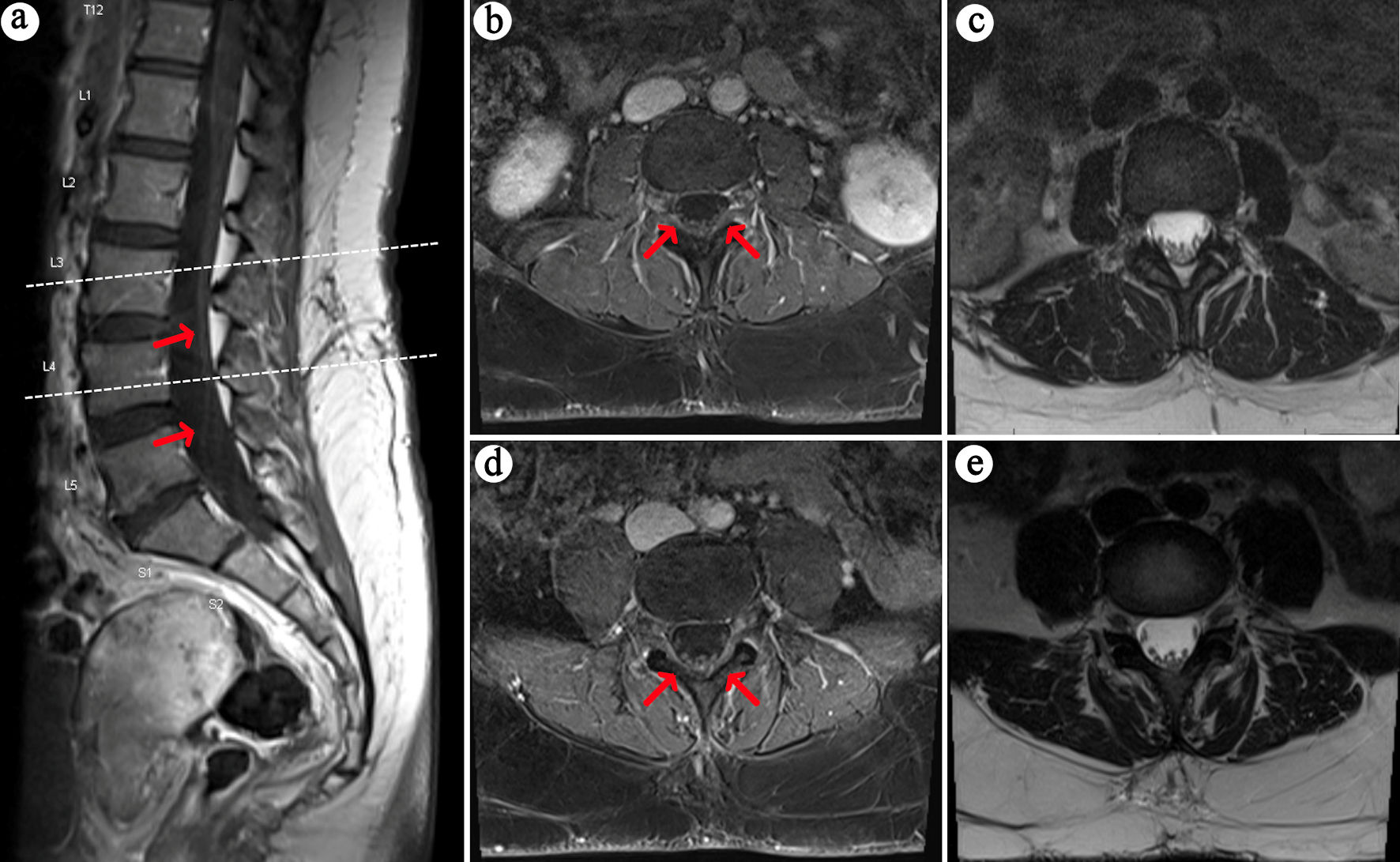

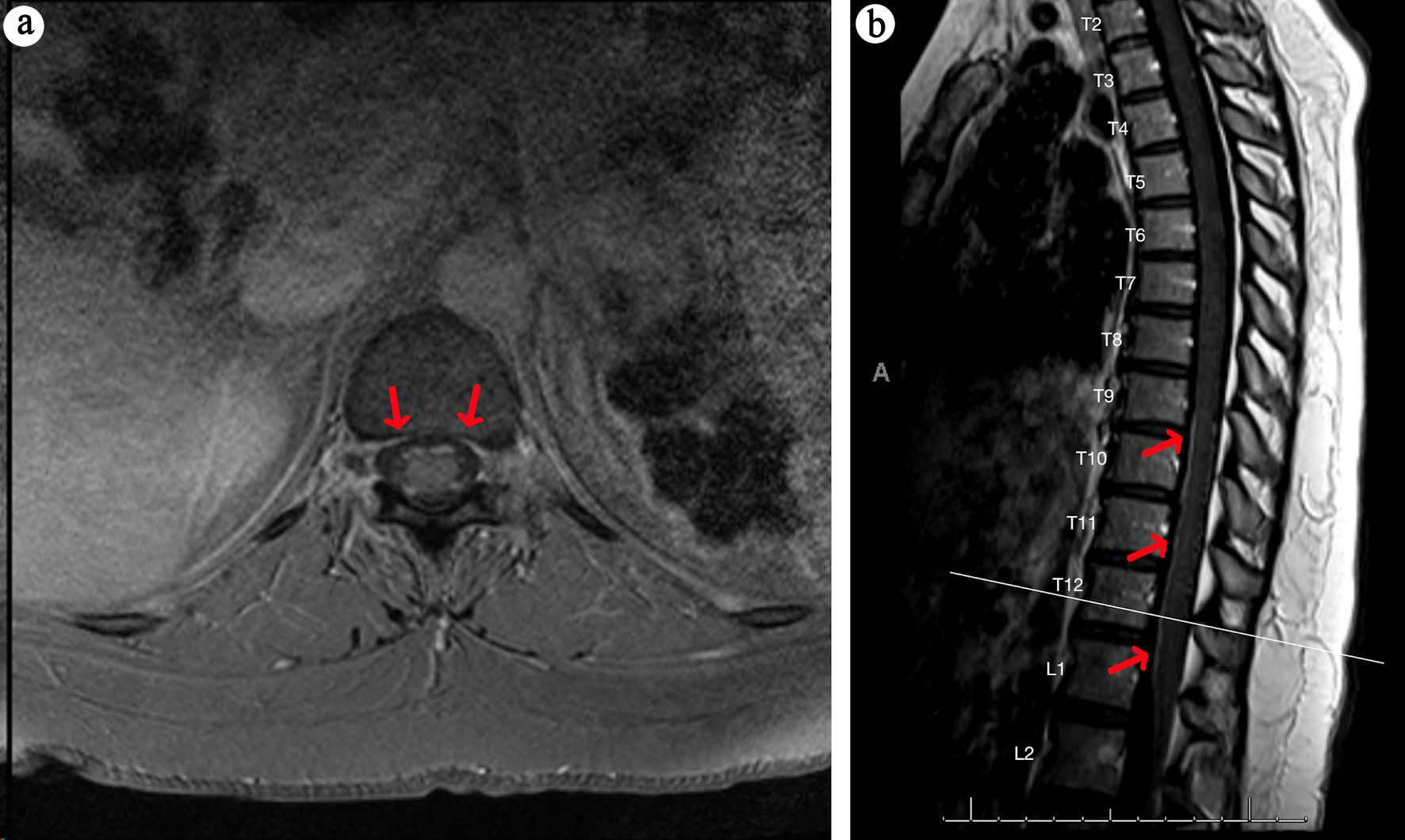

MRI of the brain and spine were obtained with and without contrast. There was T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensity within the bilateral periventricular regions (Fig. 1a, b) and right pons (Fig. 1c). The right pontine lesion additionally demonstrated restricted diffusion (Fig. 1d, e) with corresponding contrast enhancement (Fig. 1f, red arrow) associated with these FLAIR changes. Contrast enhancement was also seen within the cisternal segments of the bilateral third, fifth, and sixth cranial nerves (Fig. 1f-h). The spine imaging showed enhancement within the cauda equina roots (Fig. 2) and thoracic nerve roots (Fig. 3) but no evidence of enhancing lesions within the spinal cord. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies (EMG/NCS) performed 4 weeks after symptom onset showed no electrophysiological evidence of neuropathic dysfunction. Further imaging studies included computed tomography (CT) scans of her chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which revealed no suspicious masses, lymphadenopathy, or other pathology. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies (Table 1) displayed a mild leukocytosis, with no lymphocytic predominance and an otherwise unremarkable profile. She had five oligoclonal bands specific to the CSF, and none in her serum.

Click for large image | Figure 1. MRI brain with and without contrast. On axial T2-weighted FLAIR, there are two small periventricular white matter intensities along the bodies of the lateral ventricles (a, b, red arrows) and within the right para-midline pons (c, red arrow). On axial DWI (d), there is a small area of mild restricted diffusion in the right para-midline pons, measuring 1.4 × 1.0 cm (red arrow), with corresponding signal (red arrow) on ADC (e) and contrast enhancement on post-contrast MPRAGE (f, red arrow). Post-contrast MPRAGE imaging also shows bilateral enhancement of cranial nerves III (g, blue arrows), V (h, green arrows), and VI (f, pink arrow, unilateral only shown). MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient; MPRAGE: magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. MRI lumbar spine with contrast. On sagittal (a) and axial (b, d) T1-weighted post-contrast images, there is subtle enhancement of the cauda equina nerve roots (red arrows), with corresponding T2 axial (c, e) views. The upper dashed line on panel A corresponds to axial slices (b) and (c), whereas the lower dashed line corresponds to axial slices (d) and (e). MRI: magnetic resonance imaging. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. MRI thoracic spine with contrast. Axial (a) and sagittal (b) T1 MRI post-contrast images of the thoracic spine show subtle enhancement of the thoracic nerve roots (red arrows). MRI: magnetic resonance imaging. |

Click to view | Table 1. Serum and CSF Evaluation |

In addition to these studies, she underwent a serum autoimmune and rheumatological evaluation (Table 1) for possible causes of CNS demyelination, and it was discovered that she was positive for Sjogren’s anti-SSB antibody. However, the patient denied any history of systemic symptoms, including joint pain, ocular or mouth dryness, or parotid or submandibular swelling. The reminder of her serum evaluation was unremarkable.

Treatment

The patient was ultimately placed on a 5-day course of high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone,1 g daily. She had mild improvement in her left hemibody strength and subjective paresthesias, and she was discharged home with follow-up to outpatient neuroimmunology and rheumatology.

Follow-up and outcomes

Two months after discharge, the patient’s motor exam improved, but she reported residual numbness. Repeat brain MRI with gadolinium contrast demonstrated persistent enhancement suggestive of ongoing inflammation in the cranial nerves, so she underwent an additional 3-day course of high-dose oral steroids (prednisone 1,250 mg daily). The patient was also started on anti-B-cell therapy with ofatumumab 20 mg injection every month. Further rheumatologic workup showed elevated salivary protein 1 immunoglobulin (Ig)M antibodies, as well as elevated carbonic anhydrase VI IgG and IgM antibodies. Her neurologic symptoms have continued to improve on subsequent visits. Table 2 provides details on the patient’s longitudinal disease course.

Click to view | Table 2. Longitudinal Disease Course |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

MS is the most common autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS and is a leading cause of permanent neurological disability in young adults [1]. The diagnosis of MS has been codified in the McDonald criteria and may be summarily referred to as “multiple lesions disseminated in space and time”, without another etiology explaining the symptoms and findings [2]. Our patient would meet the criteria for MS with one clinical attack, both periventricular and infratentorial lesions, with objective clinical exam findings correlating to at least one of these lesions, and detection of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands. Her workup for other potential causes or MS mimics did reveal a positive anti-SSB antibody, indicating the possibility of an alternative etiology. However, she did not endorse any of the typical sicca syndrome associated with SS. Other MS mimics were effectively ruled out as well. Her presentation also deviated from the typical appearance of MS in several ways: her bilateral absence of lower extremity reflexes, as well as her MRI findings of enhancement of the thoracic and cauda equina nerve roots and cranial nerves, were more consistent with involvement of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Further workup was obtained to assess peripheral nerve dysfunction with EMG/NCS which was unremarkable. Finally, the CSF-specific oligoclonal bands were also suggestive of primary CNS inflammation rather than a systemic condition.

SS is an autoimmune disorder characterized by chronic inflammation of exocrine glands, traditionally leading to xerophthalmia and xerostomia [3]. However, it can also present with neurologic manifestations in both the CNS and PNS. Clinically significant neurologic symptoms affect approximately 20% of patients with SS and can be the initial manifestation of the disease in at least 25% of cases [4]. These neurologic manifestations have been documented to range widely in presentation, from sensory-motor neuropathy and cranial neuropathies to brain and spinal cord involvement, presenting with aphasia, motor deficits, or cerebellar symptoms [5-8]. Moreover, the neurologic symptoms in many cases may mimic those seen in MS, creating diagnostic challenges for the provider [9]. However, in systemic autoimmune diseases such as SS, the CSF profile typically reveals paired serum and CSF oligoclonal bands, rather than CSF-specific oligoclonal bands alone. This distinction suggests that this case most likely represents an overlap of MS and SS, rather than solely SS with CNS involvement.

Previous case reports have documented the diagnostic dilemma in the overlap syndrome of MS and SS. Mohamednour et al described a case of a 58-year-old female with a history of MS who subsequently developed sicca symptoms. Upon further investigation, it was revealed that her neurological manifestations were attributable to SS rather than MS, illustrating the diagnostic interplay between the two diseases [10]. Jung et al reported a case of SS that manifested as MS, ultimately delaying the patient’s diagnosis and treatment [11]. Thong et al described a female patient who developed multiple relapsing neurological events involving the brain and spinal cord from the age of 40 years, initially suggestive of MS. The patient then developed positive anti-nuclear antibody and anti-Ro antibody followed by sicca symptoms, confirming the diagnosis of SS [12]. Further detail and additional reports are outlined in Table 3 [10-15].

Click to view | Table 3. A Case-Based Literature Review of MS and SS Overlaps and Diagnostic Dilemmas |

While existing case reports primarily involve patients exhibiting sicca symptoms, our case highlights the critical need of considering SS in the differential diagnosis of MS with atypical neurological symptoms, even in the absence of classic sicca manifestations. In our case, the presence of cauda equina, thoracic nerve root, and cranial nerve enhancement on MRI, even in the absence of peripheral neuropathy on EMG/NCS, prompted the extensive workup for an overlap syndrome. Furthermore, it is crucial to acknowledge the temporal progression of SS, with the median age of onset at 60 years [16]. Our patient may not yet have manifested sicca symptoms, which could potentially develop later in her disease course. Therefore, she will continue to follow up with rheumatology as well as neurology.

Accurate diagnosis is not only essential for selecting the appropriate treatment, but also for counseling patients on the disease course and referral to additional proper specialists for comprehensive management. While the presence of sicca symptoms often raises suspicion for SS, it is not always necessary for consideration of an overlap diagnosis with MS. The overlap syndrome should be evaluated when MS-like patients present with atypical neurologic findings, such as PNS involvement, even in the absence of sicca symptoms. To establish the overlap, a thorough workup is necessary, including serum antibody testing, CSF studies, a Schirmer test to measure tear production, and potentially a salivary gland biopsy to assess glandular inflammation.

In general, caution should be taken to explore other similar or overlapping conditions when a patient’s presentation is not typical for MS. For example, in patients who are given a diagnosis of progressive MS, neurodegenerative syndromes should also be ruled out, including muscular dystrophies and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). If sensory symptoms are also present, Friedreich ataxia or other leukodystrophies should be considered. This is especially important, as these conditions can have life-threatening involvement of other organ systems [17, 18].

Early diagnosis is critical, as certain agents may be beneficial in one disease but could exacerbate another. For example, interferon beta, a commonly used disease-modifying therapy in MS, would not be ideal for treating SS, as type I interferons, including interferon beta, have been shown to be upregulated in SS, and their increased expression is associated with more severe clinical manifestations [19, 20]. Therefore, using interferon beta could potentially exacerbate the disease by enhancing this proinflammatory pathway, making it a less suitable option for patients with overlapping MS and SS.

Conversely, other agents may be effective across multiple diseases. In the case of overlapping MS and SS, anti-B-cell therapies have been successful therapeutic agents for both diseases [21]. In our case, after discussing her options, our patient elected to try ofatumumab as her disease modifying therapy. Ofatumumab is an anti B-cell therapy targeting CD20-positive cells, commonly used for the treatment of MS. In MS, it reduces relapse rates, decreases MRI-detected lesion activity and limits worsening of disability [22]. The mechanism is similar to rituximab, which can be used to treat SS. In SS, CD20-targeted therapies show beneficial effects on B-cell activity, glandular morphology, dryness, fatigue, and severe extraglandular manifestations [23]. After discussion with our rheumatology colleagues, it was agreed that this agent could treat both overlapping diseases, and the patient was subsequently started ofatumumab therapy. So far, her symptoms have continued to improve, and no new neurologic issues have arisen.

Learning points

This case underscores the diagnostic complexity and clinical overlap between MS and SS, particularly when patients present with atypical neurologic manifestations without the classic sicca symptoms. However, our case report is limited by the absence of a salivary gland biopsy and Schirmer test, which precludes a definitive SS diagnosis and understanding of her peripheral nerve involvement. Despite this, comprehensive diagnostic evaluation is essential for accurately diagnosing and managing such complex autoimmune conditions, especially as the treatment strategies may differ among diseases. Further research is needed to elucidate proper diagnostic evaluation and optimal treatment approaches for these overlap syndromes.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

The patient in this case has provided written consent for publication.

Author Contributions

RLS participated in patient care and contributed to the writing of the case report, preparation of the figures and tables, revisions, and management of the submission process. OT participated in patient care and contributed to the writing of the case report and revisions. NC participated in patient care and contributed to the writing of the case report and revisions. RFG participated in patient care and contributed to the writing of the case report, revisions, and continues to see the patient as their outpatient neurologist. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Oh J, Vidal-Jordana A, Montalban X. Multiple sclerosis: clinical aspects. Curr Opin Neurol. 2018;31(6):752-759.

doi pubmed - Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, Carroll WM, Coetzee T, Comi G, Correale J, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173.

doi pubmed - Tincani A, Andreoli L, Cavazzana I, Doria A, Favero M, Fenini MG, Franceschini F, et al. Novel aspects of Sjogren's syndrome in 2012. BMC Med. 2013;11:93.

doi pubmed - Fauchais AL, Magy L, Vidal E. Central and peripheral neurological complications of primary Sjogren's syndrome. Presse Med. 2012;41(9 Pt 2):e485-493.

doi pubmed - Gono T, Kawaguchi Y, Katsumata Y, Takagi K, Tochimoto A, Baba S, Okamoto Y, et al. Clinical manifestations of neurological involvement in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(4):485-490.

doi pubmed - Delalande S, de Seze J, Fauchais AL, Hachulla E, Stojkovic T, Ferriby D, Dubucquoi S, et al. Neurologic manifestations in primary Sjogren syndrome: a study of 82 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83(5):280-291.

doi pubmed - Sene D, Jallouli M, Lefaucheur JP, Saadoun D, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Maisonobe T, Diemert MC, et al. Peripheral neuropathies associated with primary Sjogren syndrome: immunologic profiles of nonataxic sensory neuropathy and sensorimotor neuropathy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90(2):133-138.

doi pubmed - Alexander GE, Provost TT, Stevens MB, Alexander EL. Sjogren syndrome: central nervous system manifestations. Neurology. 1981;31(11):1391-1396.

doi pubmed - Alexander EL, Malinow K, Lejewski JE, Jerdan MS, Provost TT, Alexander GE. Primary Sjogren's syndrome with central nervous system disease mimicking multiple sclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104(3):323-330.

doi pubmed - Mohamednour A, Durrani M. O11 Primary Sjogren’s syndrome vs MS: overlap or misdiagnosis? Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2020;4(Suppl 1):rkaa053.010.

doi - Jung SM, Lee BG, Joh GY, Cha JK, Chung WT, Kim KH. Primary Sjogren's syndrome manifested as multiple sclerosis and cutaneous erythematous lesions: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15(1):115-118.

doi pubmed - Thong BY, Venketasubramanian N. A case of Sjogren's syndrome or multiple sclerosis? A diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. Rheumatol Int. 2002;22(6):256-258.

doi pubmed - De Santi L, Costantini MC, Annunziata P. Long time interval between multiple sclerosis onset and occurrence of primary Sjogren's syndrome in a woman treated with interferon-beta. Acta Neurol Scand. 2005;112(3):194-196.

doi pubmed - Guzel S, Ozen S. An uncommon case of primary biliary cirrhosis and Hashimoto thyroiditis followed by the concurrent onset of multiple sclerosis and Sjogren syndrome. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;68(1):154-156.

doi pubmed - Liu JY, Zhao T, Zhou CK. Central nervous system involvement in primary Sjogren;s syndrome manifesting as multiple sclerosis. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2014;19(2):134-137.

pubmed - Ji J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Gender-specific incidence of autoimmune diseases from national registers. J Autoimmun. 2016;69:102-106.

doi pubmed - Kioutchoukova IP, Foster DT, Thakkar RN, Foreman MA, Burgess BJ, Toms RM, Molina Valero EE, et al. Neurologic orphan diseases: Emerging innovations and role for genetic treatments. World J Exp Med. 2023;13(4):59-74.

doi pubmed - Thakkar RN, Patel D, Kioutchoukova IP, Al-Bahou R, Reddy P, Foster DT, Lucke-Wold B. Leukodystrophy Imaging: Insights for Diagnostic Dilemmas. Med Sci (Basel). 2024;12(1):7.

doi pubmed - Plosker GL. Interferon-beta-1b: a review of its use in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2011;25(1):67-88.

doi pubmed - Muskardin TLW, Niewold TB. Type I interferon in rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(4):214-228.

doi pubmed - Brummer T, Ruck T, Meuth SG, Zipp F, Bittner S. Treatment approaches to patients with multiple sclerosis and coexisting autoimmune disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021;14:17562864211035542.

doi pubmed - Kang C, Blair HA. Ofatumumab: a review in relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. Drugs. 2022;82(1):55-62.

doi pubmed - Verstappen GM, van Nimwegen JF, Vissink A, Kroese FGM, Bootsma H. The value of rituximab treatment in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2017;182:62-71.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.