| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, October 2025, pages 000-000

Dexmedetomidine to Treat Hiccups During Anesthetic Care in an Adolescent Female

Dalton Skaggsa, Brian Hallb, Joseph D. Tobiasb, c, d

aCollege of Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

bDepartment of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA

cDepartment of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, USA

dCorresponding Author: Joseph D. Tobias, Department of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH 43205, USA

Manuscript submitted August 22, 2025, accepted September 18, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: Dexmedetomidine and Hiccups

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5198

| Abstract | ▴Top |

The clinical applications of dexmedetomidine in infants and children have included sedation during mechanical ventilation, prevention of post-anesthesia delirium, control of procedure-related pain and anxiety, and treatment of shivering. We present anecdotal experience with the use of dexmedetomidine to treat hiccups that developed intraoperatively in an adolescent following the induction of anesthesia and placement of a laryngeal mask airway. The neural pathways and neurotransmitters involved with hiccups are reviewed, options for intraoperative treatment presented, and previous reports of the use of dexmedetomidine in this clinical scenario discussed.

Keywords: Hiccups; Dexmedetomidine; Anesthetic care

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Dexmedetomidine is an α2-adrenergic agonist, first approved by the United States Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in 1999 as a short-term sedative during mechanical ventilation for adults in the intensive care unit. Subsequent FDA approval, also in adults, was later granted in 2009 for its use as a sedative/anxiolytic in monitored anesthesia care (MAC). Despite lacking FDA approval for pediatric use, it has seen widespread off-label use in infants and children due to its demonstrated efficacy and low risk for adverse hemodynamic and respiratory effects [1]. Reported pediatric clinical applications have included intensive care sedation during mechanical ventilation, prevention of post-anesthesia delirium, sedation for invasive and non-invasive procedures, control of shivering, and treatment of substance withdrawal [2, 3]. Other potential pediatric applications for dexmedetomidine continue to be explored and reported.

We present an adolescent who developed hiccups, which began to interfere with surgical care, following the induction of anesthesia and placement of a laryngeal mask airway (LMA). The hiccups resolved following the administration of a single dose of dexmedetomidine. The neural pathways and neurotransmitters involved with hiccups are reviewed, options for intraoperative treatment presented, and previous reports of the use of dexmedetomidine in this clinical scenario discussed.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Review of this case and presentation followed the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board of Nationwide Children’s Hospital (Columbus, OH). Written, informed consent was obtained along with consent for anesthesia from a parent or guardian for the use of de-identified information for publication.

The patient was a 12-year-old, 39.9-kg adolescent female with a past medical history of median arcuate ligament (MAL) syndrome status post MAL release several years prior. More recently, she had presented to an outside hospital for worsening of her chronic abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting before being brought to our institution several days later for ongoing workup of her abdominal pain as well as evaluation of abnormal dystonic movements and seizure-like activity that began during her outside admission. To evaluate her for nutcracker syndrome (renal vein compression) as the etiology of the abdominal pain and planning for a potential left renal auto-transplant, a sedated renal venogram was planned. Following a preoperative assessment which was unremarkable for her airway, cardiovascular, and respiratory examination, she was held nil per os for 8 h, and transported to the interventional radiology suite. Routine American Society of Anesthesiologists’ monitors were placed and anesthesia was induced with the intravenous administration of lidocaine (40 mg), propofol (150 mg), and fentanyl (50 µg). A size 3 LMA was placed without difficulties. Positive pressure ventilation with a peak inflating pressure of 20 cm H2O provided effective chest excursion and positive end-tidal carbon dioxide without an audible air leak. Following LMA placement, the patient started having continuous hiccups, occurring every 4 - 8 s that resulted in patient movement which interfered with the initiation of the procedure. Dexmedetomidine (12 µg) was administered as a slow bolus dose over 30 s which resulted in cessation of the hiccups within 2 min. The procedure was completed uneventfully without return of hiccups or other intraoperative problems. The LMA was removed at the completion of the procedure and the patient was transported to the post-anesthesia care unit. Her postoperative course was uneventful.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

We present anecdotal experience with the successful use of a bolus dose of dexmedetomidine to treat hiccups that developed during intraoperative anesthetic care. Hiccups are the result of spontaneous contraction of the respiratory muscles—primarily the diaphragm and intercostal muscles—accompanied by closure of the larynx [4]. Episodes can be very long-lasting, often termed persistent or “intractable,” or briefer in nature depending on the etiology. Intraoperative hiccups may be due to direct stimulation of the stomach, diaphragm or nearby nerves from the surgical procedure or irritation from anesthetic techniques such as ventilation and airway procedures, any of which can result in triggering of the hiccup reflex arc [5].

This reflex arc, while not fully understood, is generally agreed to consist of afferent pathways involving the phrenic nerve, vagus nerve, and thoracic sympathetic nerve fibers; central processing in the midbrain; and efferent pathways involving the phrenic nerve to the diaphragm and accessory nerves to the intercostal muscles [6, 7]. An array of both central and peripheral neurotransmitters are involved along these pathways, including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine, histamine, and norepinephrine, resulting in a diverse set of potential etiologies and targets for the treatment of hiccups [8].

Hiccups can be treated by a variety of means, ranging from non-pharmacologic methods like breath-holding or breathing into a paper bag, for which increased alveolar PaCO2 may be the curative outcome, or pharmacologic remedies that either treat the suspected cause of the hiccups (such as proton pump inhibitors when gastro-esophageal reflux disorder (GERD) is the suspected etiology) or pharmacologic agents that target the reflex [4]. Non-pharmacologic treatments that may be considered for hiccups specifically occurring in the intraoperative environment and can include increasing the PaCO2, briefly held inflation of the lungs, pharyngeal stimulation, or even phrenic nerve blockade [5].

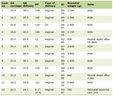

Interference with the procedure caused by the resulting patient movement often necessitates prioritizing pharmacologic treatment for a more rapid resolution. However, there remains a lack of evidence-based medicine to guide the optimal therapeutic interventions for intraoperative hiccups and no official recommendations, with most treatments relying on empiric or anecdotal evidence [9, 10]. Kranke et al reported in their systematic review that of a wide array of medications reported for this clinical use, only methylphenidate had undergone a randomized controlled trial, for which no benefit over placebo was noted [9]. Other treatments currently recommended included deepening the level of sedation or anesthesia with propofol or other general anesthetic agents, metoclopramide when the cause is suspected to be gastric in nature, anticholinergic agents, ephedrine, and when all else fails the administration of a neuromuscular blocking agent [5]. Ephedrine, an indirect acting adrenergic agonist used due to its advantage of avoiding the potential hemodynamic effects of deepening the level anesthesia, has demonstrated some efficacy in anecdotal reports [11]. Although the mechanism is not fully understood, ephedrine may suppress hiccups due to its central nervous system stimulation or a secondary bronchodilatory effect [12]. However, given ephedrine’s potential for adverse cardiovascular effects, especially in older patients, dexmedetomidine has been offered as a potential option for treating intraoperative hiccups, likely through a similar mechanism but without the same risks due to its selective α2-adrenergic agonism [13]. In addition to the case report, previous anecdotal evidence has supported the efficacy of dexmedetomidine in treating intraoperative hiccups (Table 1) [10, 13-15].

Click to view | Table 1. Previous Reports of Dexmedetomidine to Treat Hiccups |

Learning points

In summary, clinical experience has suggested the efficacy of dexmedetomidine as a potential therapeutic intervention for intraoperative hiccups in patients during general anesthesia. Hiccups in the intraoperative environment pose unique challenges with potential threats to patient safety. Inadvertent patient movement may interfere with successful completion of the procedure during both surgical procedures and radiologic imaging where patient immobility is mandatory. Although currently supported by only a handful of anecdotal cases, the apparent swift cessation of hiccups in temporal relationship to the administration of dexmedetomidine suggests that its use should be considered among other pharmacologic options in this clinical scenario. Dosing has generally included a bolus of 1 µg/kg (50 µg in adults) with two of the reports using an infusion (0.3 - 0.5 µg/kg/min) after the bolus dose to ensure completion of the procedure without further interruption. Although generally devoid of significant adverse effects, bradycardia and hypotension may occur with larger doses, rapid administration or in patients with comorbid cardiovascular diseases.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained for anesthetic care and the use of de-identified information for publication.

Author Contributions

DS: preparation of initial, subsequent, and final drafts; BH: direct patient care and review of final document; JDT: concept, writing, and review of all drafts.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

| References | ▴Top |

- Su F, Hammer GB. Dexmedetomidine: pediatric pharmacology, clinical uses and safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2011;10(1):55-66.

doi pubmed - Tobias JD. Dexmedetomidine: applications in pediatric critical care and pediatric anesthesiology. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8(2):115-131.

doi pubmed - McMorrow SP, Abramo TJ. Dexmedetomidine sedation: uses in pediatric procedural sedation outside the operating room. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(3):292-296.

doi pubmed - Becker DE. Nausea, vomiting, and hiccups: a review of mechanisms and treatment. Anesth Prog. 2010;57(4):150-156.

doi pubmed - He J, Guan A, Yang T, Fu L, Wang Y, Wang S, Ren H, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of perioperative hiccups: a narrative review. Ann Med. 2025;57(1):2474173.

doi pubmed - Bryer E, Bryer J. Persistent postoperative hiccups. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2020;2020:8867431.

doi pubmed - Chang FY, Lu CL. Hiccup: mystery, nature and treatment. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18(2):123-130.

doi pubmed - Nausheen F, Mohsin H, Lakhan SE. Neurotransmitters in hiccups. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1357.

doi pubmed - Kranke P, Eberhart LH, Morin AM, Cracknell J, Greim CA, Roewer N. Treatment of hiccup during general anaesthesia or sedation: a qualitative systematic review. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20(3):239-244.

doi pubmed - Khatri S, Hannurkar P. Understanding and treating laryngeal mask airway-induced intraoperative hiccups. Cureus. 2024;16(9):e69782.

doi pubmed - Sohn YZ, Conrad LJ, Katz RL. Hiccup and ephedrine. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1978;25(5):431-432.

doi pubmed - Bahadoori A, Shafa A, Ayoub T. Comparison the effects of ephedrine and lidocaine in treatment of intraoperative hiccups in gynecologic surgery under sedation. Adv Biomed Res. 2018;7:146.

doi pubmed - Koteswara CM, Dubey JK. Management of laryngeal mask airway induced hiccups using dexmedetomedine. Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57(1):85.

doi pubmed - El-Tahan MR, Doyle DJ, Telmesani L, Al'Ghamdi A, Khidr AM, Abdeen MM. Dexmedetomidine suppresses intractable hiccup during anesthesia for cochlear implantation. J Clin Anesth. 2016;31:208-211.

doi pubmed - Krishnakumar M, Srinivasaiah B, Naik SS, Goyal A. Propofol-induced hiccups in MRI suite treated with dexmedetomidine. Saudi J Anaesth. 2023;17(3):450-451.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.