| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 12, December 2025, pages 487-492

Anesthetic Challenges in the Management of a Rare Giant Biliary Mucinous Cystadenoma With Major Vascular Compression

Mahmoud Elnahasa, c , Sieglinde Hochreina, Jochen Thiesb, Mina Khalila, Patrik Topfa, Philip Langa

aDepartment of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care Medicine, and Pain Therapy, Sozialstiftung Bamberg, 9049 Bamberg, Germany

bDepartment of General and Hepatobiliary Surgery, Sozialstiftung Bamberg, 9049 Bamberg, Germany

cCorresponding Author: Mahmoud Elnahas, Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care Medicine, and Pain Therapy, Sozialstiftung Bamberg, 9049 Bamberg, Germany

Manuscript submitted August 10, 2025, accepted October 21, 2025, published online November 22, 2025

Short title: Anesthesia in Biliary Cystadenoma With Vessel Compression

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5187

| Abstract | ▴Top |

The anesthetic management of a patient with an extensive biliary mucinous cystadenoma presents unique challenges that necessitate careful consideration of the patient’s physiological status, potential cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic changes resulting from elevated intra-abdominal pressure and possible compression of major abdominal vessels or, as well as the requirement for meticulous fluid and electrolyte management due to fluid and blood loss, and the provision of appropriate analgesic therapy. This case report describes the anesthetic management of a 22-year-old female diagnosed with a sizeable biliary mucinous cystadenoma measuring approximately 32 × 22 × 24 cm. It emphasizes the anesthetic considerations essential to ensure a safe and successful outcome.

Keywords: Biliary mucinous cystadenoma; Re-expansion pulmonary edema; Supine hypotension syndrome; Hemodynamic changes; Elevated intra-abdominal pressure; Difficult airway

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Biliary mucinous cystadenomas are rare cystic neoplasms originating from the biliary epithelium, typically with a predominant intrahepatic location, and accounting for less than 5% of all hepatic cysts. While these neoplasms are considered benign, they are associated with premalignant potential [1]. These lesions are more frequently observed in middle-aged women, often presenting with a spectrum of nonspecific symptoms that complicate early identification. Clinical manifestations typically stem from the growing mass effect of the cyst on surrounding structures, which can induce varied complaints such as persistent epigastric or right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain, obstructive jaundice due to compression of bile ducts, or episodes of cholangitis arising from secondary infection or obstruction [2]. The insidious onset and variability of these symptoms frequently mimic more common benign conditions, contributing to diagnostic delays.

Furthermore, distinguishing these potentially premalignant lesions from other benign cystic formations, such as simple cysts or hydatid cysts, or even from frankly malignant tumors, such as cystadenocarcinoma, poses a significant challenge for clinicians. Standard imaging modalities, including ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), often reveal cystic lesions but may lack the definitive features required to differentiate between benign and malignant characteristics reliably or to delineate the mucinous nature of the cyst precisely. Similarly, endoscopic techniques may provide limited diagnostic yield in accurately distinguishing the actual pathology, further underscoring the diagnostic dilemma inherent in these rare tumors [3, 4]. However, the surgical resection of biliary mucinous cystadenomas and their anesthetic management, particularly for large or complex lesions, present significant challenges. It necessitates a comprehensive perioperative strategy, including thorough preoperative assessment, meticulous intraoperative fluid management, continuous hemodynamic monitoring, and careful administration of vasoactive drugs and blood products. Anesthesiologists must be prepared for potential complications such as significant blood loss, hemodynamic instability, and the physiological impact of rapid decompression during tumor removal. This complex perioperative care underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary team approach to ensure optimal patient outcomes.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 22-year-old female patient was referred to our interdisciplinary emergency department by a general practitioner for evaluation of a suspected acute abdomen. The patient described a distended abdomen that had been present for about 4 weeks, accompanied by a diffuse sense of abdominal distention and pain localized to the RUQ. Additionally, the patient reported experiencing persistent flatulence. The physical examination revealed a markedly distended abdomen with a palpable mass in the RUQ and localized tenderness. There were no signs or symptoms of jaundice.

Abdominal ultrasonography (Fig. 1) revealed a sizeable septated and predominantly hypoechoic mass compressing the diaphragm superiorly, accompanied by free intraperitoneal fluid. Further diagnostic imaging with an abdominal MRI scan demonstrated findings consistent with liver echinococcosis, without evidence of cholestasis, but the presence of significant ascites, indicating the possibility of a ruptured cyst. Serological testing for Echinococcus was negative, while tumor marker analysis showed a significantly elevated carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) level of 460.3 U/mL (reference range: < 37 U/mL) and cancer antigen 125 (CA125) level of 247.3 U/mL (reference range: < 35 U/mL).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Abdominal ultrasonography showing a sizeable, septated, predominantly hypoechoic mass. |

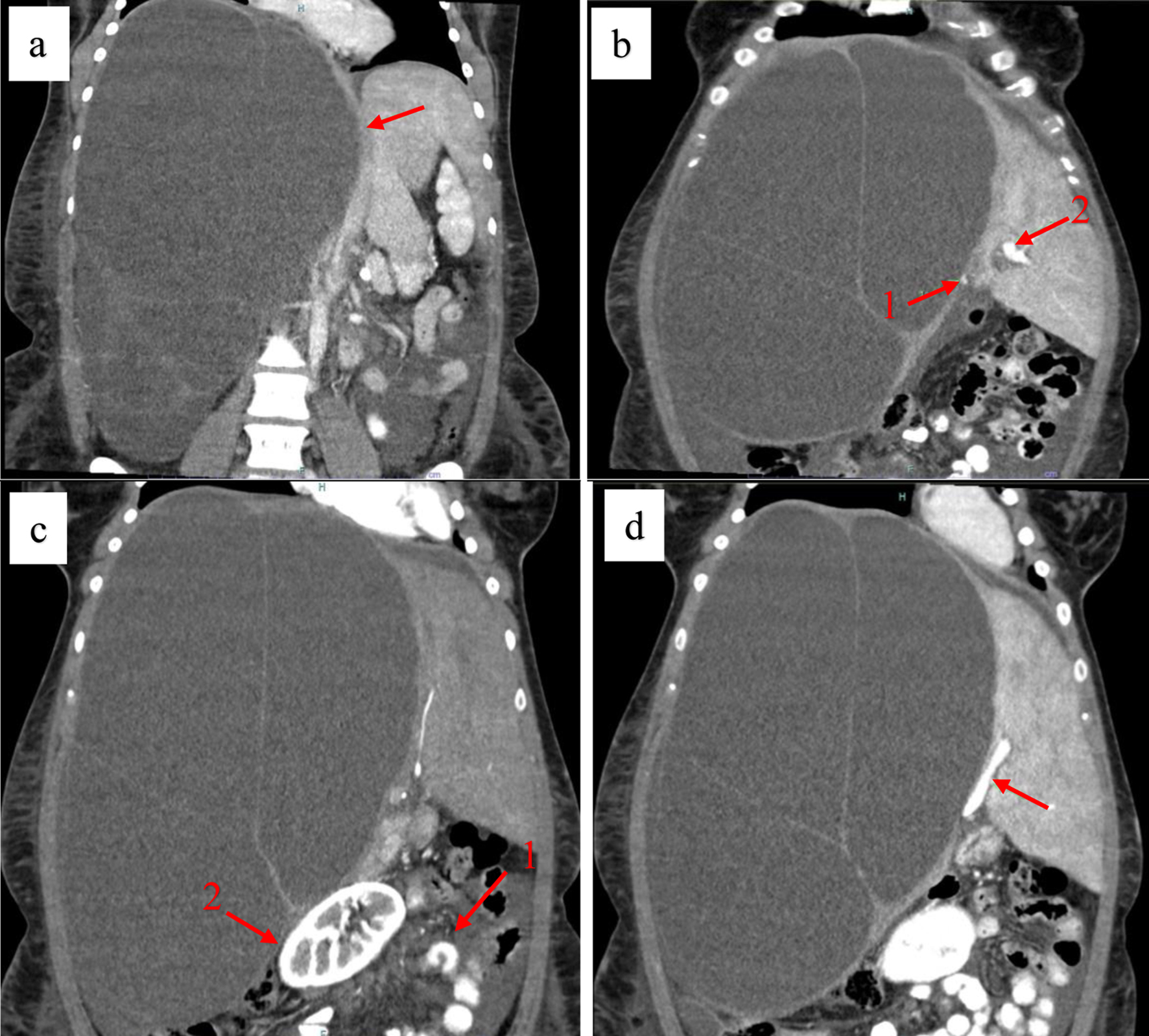

Abdominal computed tomography imaging with contrast revealed a massive, septated liver cyst in the right hepatic lobe measuring approximately 32 × 22 × 24 cm. The cyst had displaced the abdominal organs towards the left side of the abdomen and was associated with surrounding ascites. Furthermore, the inferior vena cava could not be traced to its entry into the right atrium, and the main right portal vein branch appeared significantly compressed (Fig. 2).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Coronal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showing a giant biliary mucinous cystadenoma. (a) Compression of the inferior vena cava (red arrow). (b) Compression of the left (arrow 1) and the right (arrow 2) portal veins. (c) Displacement of abdominal structures (arrow 1) and the right kidney (arrow 2) to the left. (d) Compression of the left portal vein (red arrow). |

Based on a multidisciplinary patient evaluation involving hepatobiliary surgeons, radiologists, gastroenterologists, gynecologists, and anesthesiologists, and considering the clinical and radiological findings, the presumptive diagnosis was a biliary cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma, which necessitated prompt surgical intervention. Consequently, the patient was scheduled for an elective exploratory laparotomy to ascertain the definitive diagnosis via intraoperative biopsy and proceed with complete surgical excision of the cystic mass.

Anesthesiological management

The preoperative anesthesiological evaluation revealed a 22-year-old female patient with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification of II. She weighed 85 kg and was 165 cm tall. Her body mass index (BMI) was 31.2, placing her in the obesity class I. The patient had no significant past medical history. Airway assessment showed Mallampati I with normal mouth opening and thyromental distance. Cardiovascular examination findings were unremarkable. Pulmonary examination revealed decreased breath sounds at the right lung base due to diaphragmatic elevation from the massive abdominal mass. Preoperative laboratory tests were within normal limits. However, the liver function tests were slightly elevated, showing mildly increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 47 U/L (reference range: < 35 U/L) and alanine transaminase (ALT) at 42 U/L (reference range: 10 - 34 U/L), while total bilirubin remained within the normal range (0.1 - 1.2 mg/dL). The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a normal sinus rhythm without any abnormalities.

The patient was informed about the proposed anesthetic plan, which included general anesthesia, regional anesthesia with an epidural catheter, and the placement of a central venous catheter, an arterial line, and a urinary catheter. The patient was also made aware of the potential risks, such as the possibility of bleeding and the need for blood or blood product transfusion, as well as the requirement for postoperative intensive care. Adequate blood products, including packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets were cross-matched and readily available in anticipation of potential hemorrhage or coagulopathy during or after the surgical procedure. After arrival in the anesthetic preparation room and undergoing standard monitoring, the patient received 2 mg of midazolam intravenously as an anxiolytic. Then, a thoracic epidural catheter was placed at the T6-T7 interspace under aseptic conditions with the patient in the sitting position. The epidural catheter was secured to provide intra- and postoperative pain management. After administering a 3 mL test dose of 0.75% ropivacaine, the epidural catheter was functioning correctly, without evidence of intrathecal or intravascular placement.

The patient was positioned supine with a slight left lateral tilt to relieve pressure on the inferior vena cava. Before induction, an arterial line was placed in the right radial artery under local anesthetic. Due to the high risk of aspiration from increased intra-abdominal pressure, rapid sequence induction was performed. Preoxygenation was conducted by administering 100% oxygen for approximately 3 min. Anesthetic induction was achieved using sufentanil 25 µg, propofol 150 mg, and rocuronium 70 mg. The intubation was performed using video laryngoscopy. Anesthesia was maintained using sevoflurane, along with intermittent epidural boluses of ropivacaine 0.75%. After induction, a triple-lumen central venous catheter was inserted into the right internal jugular vein under ultrasound guidance. Baseline central venous pressure was 14 mm Hg, reflecting the increased intra-abdominal pressure from the massive tumor. Two large-bore peripheral intravenous lines were also established. A lung-protective ventilation strategy was employed, utilizing pressure-controlled mode with tidal volumes in the range of 6 - 8 mL/kg, and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) was set at approximately 10 cm H2O. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis (PAP) was administered according to the guidelines.

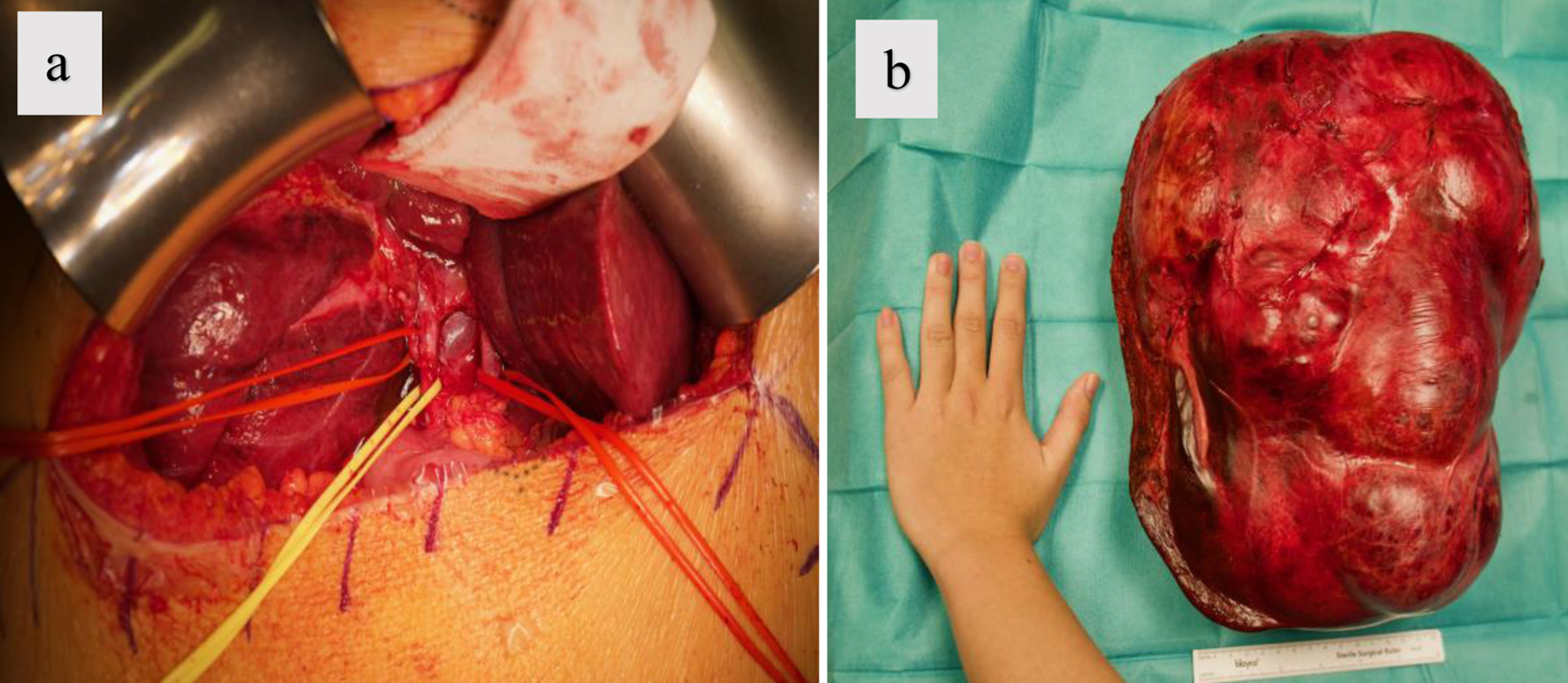

An RUQ laparotomy was performed. Following the initial abdominal incision, 3 L of turbid ascitic fluid were aspirated, with the discoloration likely attributed to lymph. After placing a retractor, an attempt was made to resect the massive tumor from the retroperitoneal and lower abdominal regions. However, this proved unfeasible due to the massive size of the tumor. Consequently, the decision was made to puncture the cystic tumor directly, and approximately 7 L of brownish-tinged fluid were gradually aspirated from the tumor at a rate of 0.5 to 1 L/min. During the procedure, close communication was maintained with the surgical team. Maintaining close hemodynamic and pulmonary monitoring was crucial during drainage to prevent hypotension and re-expansion pulmonary edema (RPE). Despite this, the patient experienced a transient decrease in blood pressure and central venous pressure due to the reduction in intra-abdominal pressure. The resection of the massive tumor was challenging and was performed carefully (Fig. 3a). A right hepatectomy, together with a cholecystectomy, was also necessary to be performed.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Surgical images obtained after laparotomy illustrating: (a) careful dissection with hepatic vessels and bile duct marked using color-coded loops; (b) the resected tumor measuring approximately 32 × 22 × 24 cm. |

There was blood loss of approximately 2,500 mL at the end of the extensive tumor resection (Fig. 3b). This blood loss was managed with fluid resuscitation using balanced crystalloid and colloid solutions. Due to a hemoglobin level of 6.7 g/dL, two units of packed red blood cells were transfused. Additionally, 1 g of tranexamic acid was administered, followed by 2 g of fibrinogen when the level was 70 mg/dL. Ionized calcium (iCa2+) was maintained above 1.2 mmol/L, and the patient was kept warm between 36.5 and 37 °C throughout the procedure using an active warming device and infusion warmer. A norepinephrine infusion was required to maintain adequate perfusion pressure between 0.1 and 0.15 µg/kg/min. Arterial blood gases were monitored regularly, showing adequate oxygenation and normal acid-base status throughout the procedure. The patient was extubated without any issues at the end of the operation and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), where she was stabilized and monitored closely. The norepinephrine infusion was successfully discontinued, and the patient remained comfortable and pain-free, allowing for transfer to the surgical ward after 2 days.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case highlights the anesthetic management of a rare and exceptionally large biliary mucinous cystadenoma that exerted substantial vascular and respiratory compression, resulting in a series of unique perioperative challenges. While biliary mucinous cystadenomas themselves are uncommon, the extraordinary size of this tumor, along with its significant mass effect on both the diaphragm and major vascular structures, including the inferior vena cava and aorta, makes this case particularly notable. Such anatomical distortion created a complex interplay between respiratory mechanics, cardiovascular stability, and airway management that is rarely encountered in routine anesthetic care. The mass effect of large abdominal tumors can lead to impaired respiratory function by displacing the diaphragm cephalically, causing narrowing of the chest cavity [5]. That reduces functional residual capacity and lung compliance, increasing the risk of atelectasis, hypoxia, and ventilation-perfusion mismatch, making intraoperative ventilation more challenging by increasing high peak airway pressures [6]. Preoperative assessment of arterial blood gases and pulmonary function tests may be necessary.

Additionally, evaluation for difficult intubation is vital, and in some cases, awake fiberoptic intubation may be indicated. Rapid sequence induction was used in our case due to high aspiration risk from increased intra-abdominal pressure [7]. Once the patient is intubated, strategies for optimizing ventilation include using lower tidal volumes and positive end-expiratory pressure to improve oxygenation and prevent alveolar collapse. RPE is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication that can occur following rapid re-inflation of a collapsed lung after surgical intervention or drainage. Rapid lung re-expansion increases pulmonary capillary permeability, leading to fluid leakage into the interstitial and alveolar spaces, and is exacerbated by prolonged lung collapse and rapid re-expansion [8]. To mitigate this risk, slow and controlled drainage should be considered (0.5 - 1 L/min), alongside balanced fluid management to avoid overload, which may help to prevent its occurrence [6-8].

Elevated intra-abdominal pressure from the cyst can compress the inferior vena cava and aorta, leading to a decrease in right ventricular preload and an increase in left ventricular afterload. This results in reduced venous return, cardiac output (CO), and increased jugular venous pressure and systemic vascular resistance, ultimately causing hypotension and tachycardia [9]. Therefore, comprehensive cardiovascular assessment, including transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and electrocardiography, is essential [6, 7]. Preoperative imaging is crucial for identifying any potential compression or invasion of critical structures, such as the inferior vena cava, aorta, and portal vein. This information guides anesthetic and hemodynamic planning.

Furthermore, the risk of considerable intraoperative bleeding must be anticipated, necessitating adequate preparation with packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and clotting factors [10]. Positioning the patient in a left lateral decumbent position can help reduce compression of the inferior vena cava and aorta, thereby preventing the development of supine hypotension syndrome [11]. Close monitoring of the patient’s hemodynamics is essential during the surgical procedure. This monitoring includes continuous monitoring of arterial blood pressure and CO, as well as assessment of dynamic preload variables, such as pulse pressure variation (PPV) or stroke volume variation (SVV), to evaluate fluid responsiveness. Additionally, intraoperative monitoring of lactate levels and central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) can provide valuable insights into tissue oxygenation, particularly when hypoperfusion is a concern. When feasible, transesophageal or transthoracic echocardiography may be considered to guide hemodynamic management, especially in patients with hemodynamic instability. This comprehensive approach allows the anesthesia team to effectively manage the patient’s cardiovascular status throughout the surgical intervention [6, 11, 13]. To mitigate the risk of severe hypotension and cardiac arrhythmias that may occur due to prolonged surgical manipulation or abrupt decompression following tumor resection or aspiration, a target-directed fluid therapy approach was employed to maintain fluid balance, along with the administration of vasopressors as required [6-13]. Preoperative assessment of hepatic function and coagulation profile is essential. Evaluation of liver enzymes, bilirubin, albumin, and coagulation parameters is crucial, as these factors impact drug metabolism and the risk of bleeding. Accordingly, any necessary interventions involving blood products or clotting factor administration should be carefully planned [14, 15]. ICU admission is often required for hemodynamic and pulmonary monitoring. Respiratory support, including non-invasive ventilation and mobilization, helps prevent atelectasis and post-extubation edema. Transfusion of blood or blood products may be necessary. Continuous liver function and coagulation profile monitoring are essential to detect and manage postoperative hepatic dysfunction or coagulopathy. Analgesia should follow a multimodal strategy using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, and regional anesthesia (e.g., epidural, transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block). Careful monitoring for signs of postoperative complications such as bleeding, infection, and venous thromboembolism is essential for early intervention and improved patient outcomes [16].

Learning points

Successful anesthetic management of massive biliary mucinous cystadenomas demands comprehensive preoperative evaluation, invasive intraoperative monitoring, cautious fluid management, multimodal analgesia approaches, and vigilant postoperative care. The interdisciplinary collaboration between surgical and anesthesia teams is essential for optimizing patient outcomes in these challenging cases.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the patient’s cooperation and consent to publish this case report, including the use of clinical data and images. We also extend our sincere appreciation to the anesthesiology, surgical, and intensive care teams for their expertise and dedicated care.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for this case report.

Author Contributions

Mahmoud Elnahas contributed to the initial manuscript write-up, literature review, and editing. Mahmoud Elnahas, Sieglinde Hochrein, Patrik Topf, and Jochen Thies managed the patient. Philip Lang and Mina Khalil were responsible for the final writing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data supporting the findings of this case report are included within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

ALT: alanine transaminase; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; BMI: body mass index; CA19-9: carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CA125: cancer antigen 125; CO: cardiac output; ECG: electrocardiogram; iCa2+: ionized calcium; ICU: intensive care unit; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PAP: perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure; PPV: pulse pressure variation; RPE: re-expansion pulmonary edema; RUQ: right upper quadrant; ScvO2: central venous oxygen saturation; SVV: stroke volume variation; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography

| References | ▴Top |

- Averbukh LD, Wu DC, Cho WC, Wu GY. Biliary mucinous cystadenoma: a review of the literature. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2019;7:1.

doi - Soochan D, Keough V, Wanless I, Molinari M. Intra and extra-hepatic cystadenoma of the biliary duct. Review of literature and radiological and pathological characteristics of a very rare case. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012.

doi pubmed - Tholomier C, Wang Y, Aleynikova O, Vanounou T, Pelletier JS. Biliary mucinous cystic neoplasm mimicking a hydatid cyst: a case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19(1):103.

doi pubmed - Rayapudi K, Schmitt T, Olyaee M. Filling defect on ERCP: biliary cystadenoma, a rare tumor. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2013;7(1):7-13.

doi pubmed - Onal O. Anesthetic approach to giant ovary cyst in the adolescent. MOJ Surg. 2015;2(3).

doi - Grajdieru O, Petrisor C, Bodolea C, Tomuleasa C, Constantinescu C. Anaesthesia management for giant intraabdominal tumours: a case series study. J Clin Med. 2024;13(5).

doi pubmed - Ohashi N, Imai H, Tobita T, Ishii H, Baba H. Anesthetic management in a patient with giant growing teratoma syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:32.

doi pubmed - Antonini-Canterin F, De Biasio M, Baldessin F, Mione V, Mercante WP, Nicolosi GL. Re-expansion unilateral pulmonary oedema after surgical drainage of a giant hepatic cyst: a case report. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2007;8(3):188-191.

doi pubmed - Lagosz P, Sokolski M, Biegus J, Tycinska A, Zymlinski R. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure: A review of current knowledge. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10(10):3005-3013.

doi pubmed - Snowden C, Prentis J. Anesthesia for hepatobiliary surgery. Anesthesiol Clin. 2015;33(1):125-141.

doi pubmed - Sugai Y, Yamoto M, Obayashi J, Tsukui T, Nomura A, Miyake H, Fukumoto K, et al. Laparoscopic resection for retroperitoneum ganglioneuroma with Supine hypotension syndrome. Surg Case Rep. 2024;10(1):192.

doi pubmed - Saugel B, Annecke T, Bein B, Flick M, Goepfert M, Gruenewald M, Habicher M, et al. Intraoperative haemodynamic monitoring and management of adults having non-cardiac surgery: Guidelines of the German Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine in collaboration with the German Association of the Scientific Medical Societies. J Clin Monit Comput. 2024;38(5):945-959.

doi pubmed - Xiang B, Yi M, Yin H, Chen R, Yuan F. Anesthesia management of an aged patient with giant abdominal tumor and large hiatal hernia: A case report and literature review. Front Surg. 2022;9:921887.

doi pubmed - Zhang FB, Zhang AM, Zhang ZB, Huang X, Wang XT, Dong JH. Preoperative differential diagnosis between intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: a single-center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(35):12595-12601.

doi pubmed - Rai R, Nagral S, Nagral A. Surgery in a patient with liver disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012;2(3):238-246.

doi pubmed - Grade M, Quintel M, Ghadimi BM. Standard perioperative management in gastrointestinal surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396(5):591-606.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.