| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, October 2025, pages 000-000

A Rare Co-Occurrence of Gastric Heterotopia and Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction: An Attempt to Explain If There Is a Need to Explore Possible Syndromic Link

Lana Alhalabia, Omar Alhalabia, Asad Khanb, Jafer Alib, Prakash Guptab, Mohamed H. Ahmedc, d, e, f

aMedical School, The University of Buckingham, Buckingham MK18 1EG, UK

bDepartment of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Eaglestone, Milton Keynes MK6 5LD, UK

cDepartment of Geriatric Medicine, Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Eaglestone, Milton Keynes MK6 5LD, UK

dDepartment of Medicine and HIV Metabolic Clinic, Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Eaglestone, Milton Keynes MK6 5LD, UK

eHonorary Senior Lecturer of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Buckingham, Buckingham MK18 1EG, UK

fCorresponding Author: Mohamed Hassan Ahmed, Department of Medicine and HIV Metabolic Clinic, Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Eaglestone, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, UK

Manuscript submitted August 9, 2025, accepted September 30, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: Co-Occurrence of GHT and ANS Dysfunction

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5185

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Gastric heterotopia (GHT) is the presence of gastric mucosa outside the stomach, including in the rectum. A 59-year-old man presented with rectal bleeding and altered bowel habits, along with long-standing low blood pressure and erectile dysfunction. Investigations confirmed rectal GHT, initially managed conservatively, followed by mucosectomy, which improved his gastrointestinal symptoms. However, persistent dizziness, blurred vision, and urinary symptoms prompted neurological evaluation, revealing autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction. This case represents the first reported co-occurrence of GHT and ANS dysfunction. Although both conditions are rare and typically unrelated, their co-presentation suggests a possible link. We hypothesize that chronic inflammation or neurochemical signaling from ectopic gastric mucosa may contribute to autonomic disruption. Further research is needed to explore shared pathophysiological mechanisms.

Keywords: Gastric heterotopia; Autonomic nervous system dysfunction; Familial dysautonomia; Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome; Hirschsprung disease

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The definition of heterotopia is the ectopic location of normal physiological tissue. While gastric heterotopia (GHT) is commonly found in the foregut and midgut, its presence in the hindgut is less frequently reported [1]. Some commonly reported places to find GHT include the esophagus, Meckel’s diverticulum, and gallbladder [2-4]. Clinical presentations vary depending on the location. For example, GHT in the gallbladder is usually asymptomatic, whereas in the esophagus it can present with dysphasia and dyspepsia [2, 3].

There are several theories regarding the etiology of GHT. In the foregut, it is thought to be a congenital deformity due to an abnormal descent of the stomach. Some theories also propose an acquired mechanism, in which acute insult or tissue inflammation leads to metaplasia [5]. Patients who presented with anorectal specific symptoms were generally younger, often pediatric, and commonly developed more severe GHT-related complications. These included ulcers, fistula, and bowel perforation. Asymptomatic patients were discovered when undergoing investigations for positive fecal occult results and/or iron deficiency anemia [6]. The clinical presentation of GHT depends on the location and severity of the condition, ranging from no symptoms to complications like bowel perforation. The most common symptoms that patients may present with included hematochezia, abdominal pain, anal pain, and tenesmus, with hematochezia and abdominal pain being the most frequent presentations [7].

GHT can mimic polyps, ulcers, or diverticula on endoscopic views. A biopsy is essential for the diagnosis of GHT. Histological examination typically reveals gastric-type mucosa (pyloric and oxyntic) adjacent to rectal mucosa, without evidence of dysplasia or metaplasia [7]. Rectal GHT remains a rare finding [5]. Reports of GHT in the rectum however are less common [5].

There have been reported cases of malignancy arising from heterotopia. The most notable is adenocarcinoma developing from GHT found in the esophagus, jejunum, ilium and colon. GHT harbors a risk of becoming sinister, in addition to reducing the quality of life of patients. Therefore, definitive treatment should be considered for all patients with GHT [6]. However, no association was reported between autonomic nervous dysfunction and GHT.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulates involuntary homeostatic functions including heart rate, blood pressure, thermoregulation, urinary function, and gastrointestinal motility. This system is divided into three distinct components: sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric nervous systems. Dysfunction may affect one or more of these components and can result from a variety of causes. Multiple of these causes can occur simultaneously in the same patient. Autonomic dysfunction may be inherited (e.g., amyloidosis, familial dysautonomia) or acquired (e.g., Guillain-Barre syndrome, diabetic neuropathy, vitamin B12 deficiency, Parkinson’s disease, trauma) [8]. Clinical presentation varies according to the system involved. Cardiovascular involvement can present with orthostatic hypotension, syncope. Gastrointestinal symptoms can include gastroparesis, constipation, and diarrhea. Urogenital symptoms can manifest as urinary incontinence, retention, and sexual dysfunction [9].

Autonomic dysfunction can often take years to diagnose. Pharmacological managements of symptoms of autonomic dysfunction include midodrine or fludrocortisone for orthostatic hypotension, prokinetics for gastrointestinal dysmotility, and anticholinergic agents for bladder dysfunction [8]. Non-pharmacological options include high sodium diets and compression stockings for hypotension, and long-term catheterization for urinary retention. The prognosis is poor due to the significant impact on morbidity and quality of life [8].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

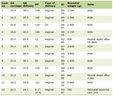

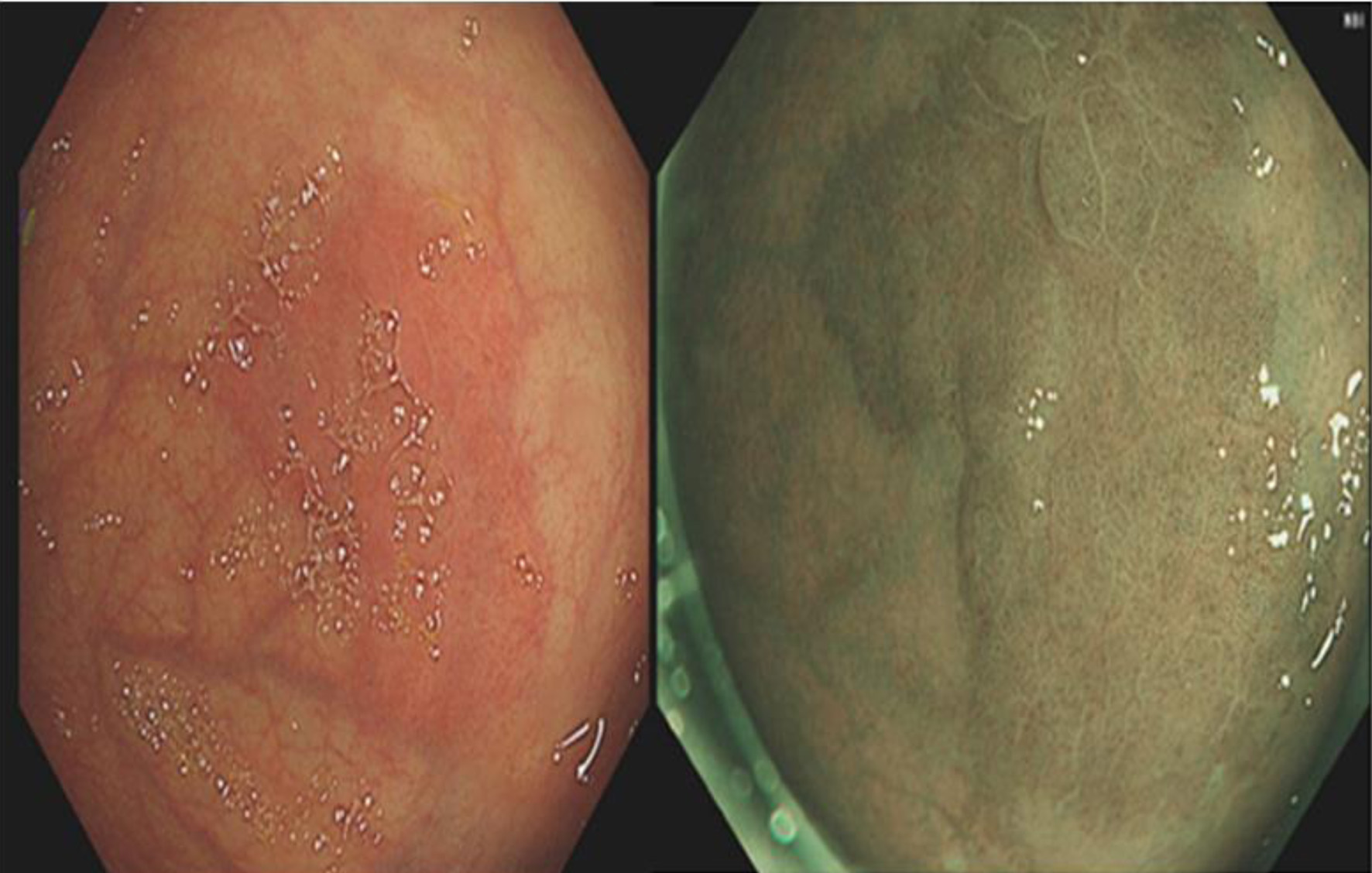

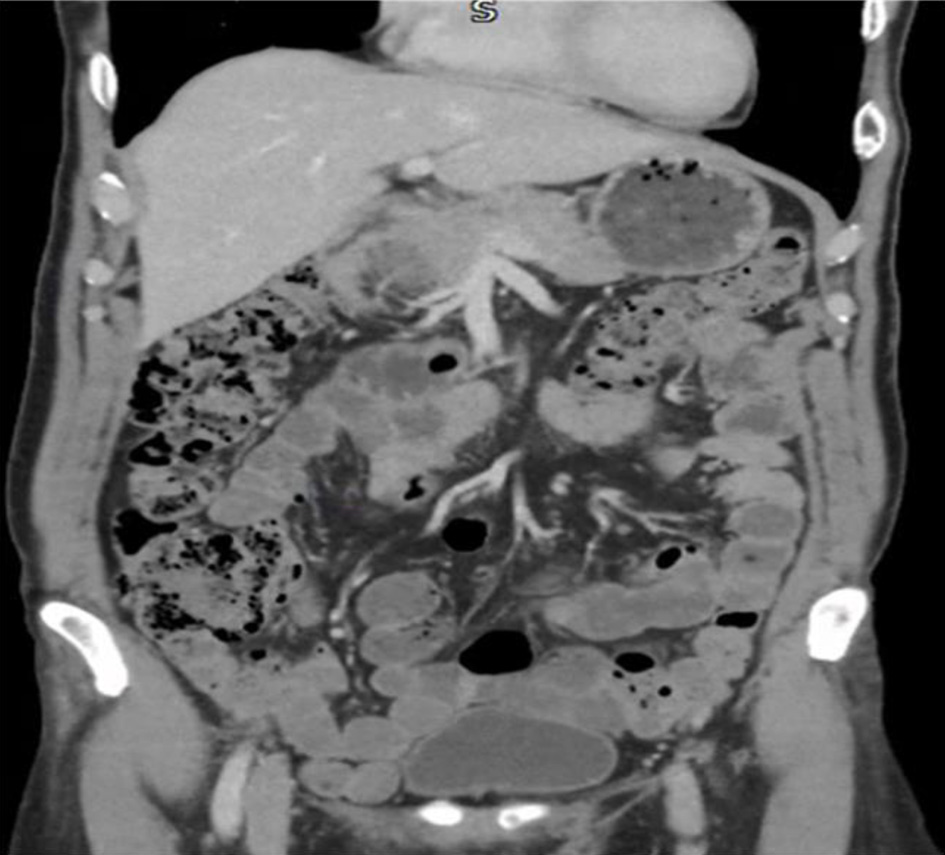

A 59-year-old Iranian male presented to his general practitioner (GP) with per-rectal bleeding and change in bowel habits. Blood investigation ordered by the GP showed no evidence of anemia but had a low white blood cell (WBC), red blood cell (RBC), and hematocrit. Table 1 displays the blood investigation results at the time of his initial presentation. He was subsequently referred via the 2-week wait pathway for colonoscopy. The colonoscopy revealed two polyps in the colon as well as a well circumscribed 15 mm erythematous patch in the rectum as shown in Figure 1. The polyps were removed, and the patch was biopsied at the time of colonoscopy. Pathology reported the polyps to be tubular adenomas with low grade dysplasia. The report also revealed the erythematous patch to consist of fragments of gastric fundic-type mucosa. Figure 1 displays the GHT found in the rectum. None of the biopsies showed evidence of dysplasia or malignancy. He also underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis (CT CAP) which were unremarkable as seen in Figure 2.

Click to view | Table 1. Blood Test and Corresponding Result at the Time of Initial Presentation to GP |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Colonoscopy showing gastric heterotopia identified in the rectum with traditional white light endoscopy (left) as well as narrow band imaging (right). The heterotopia is a 15-mm well circumscribed erythematous patch. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Computed tomography imaging did not reveal any abnormality. There was no evidence of malignancy. |

A repeat sigmoidoscopy was completed 2 months after the initial colonoscopy and the lesions were re-biopsied. Pathology report for the second biopsy highlighted that the repeat biopsy contains fragments lined by foveolar epithelium with underlying specialized gastric glands. There were focal intestinal metaplasia and mild patchy chronic inflammation. A diagnosis of GHT was made approximately 3 months from when the patient was first seen by his GP. For the following year, the lesion was regularly reviewed under surveillance and ultimately removed via endoscopic mucosectomy approximately 1 year after diagnosis.

Importantly, the patient has had constitutional low blood pressure. These episodes occur when he stands up, but also at night. He describes episodes of his blood pressure dropping to 50 mm Hg and feeling palpitations in the middle of the night. Episodes of dizziness, blurred vision, and light-headedness were triggered by physical exertion and standing. The latter had progressed significantly and was started on Midodrine with mild benefit. At the age of 59, he presented to his GP with symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency, weak stream, and feeling of incomplete bladder emptying. An ultrasound showed a normal prostate volume of 30 mL, however a large post void volume of 291 mL. His prostate specific antigen at the time was at a normal level of 0.2 ng/mL and on examination his prostate was normal. As he had no evidence of benign prostate hypertrophy, he went on to have urodynamic studies. This investigation showed underactive bladder and poor pressures during the voiding phase. He was ultimately diagnosed with ANS dysfunction 4 years after he first presented with urinary symptoms. Management with intermittent self-catheterization was recommended to help with bladder voiding.

Further neurological examination revealed mild parkinsonism in his right upper limb. The rest of the examinations including vibration sense, deep tendon reflexes, muscle tone and volume, were all within normal limits and he was not found to have any cerebellar deficit.

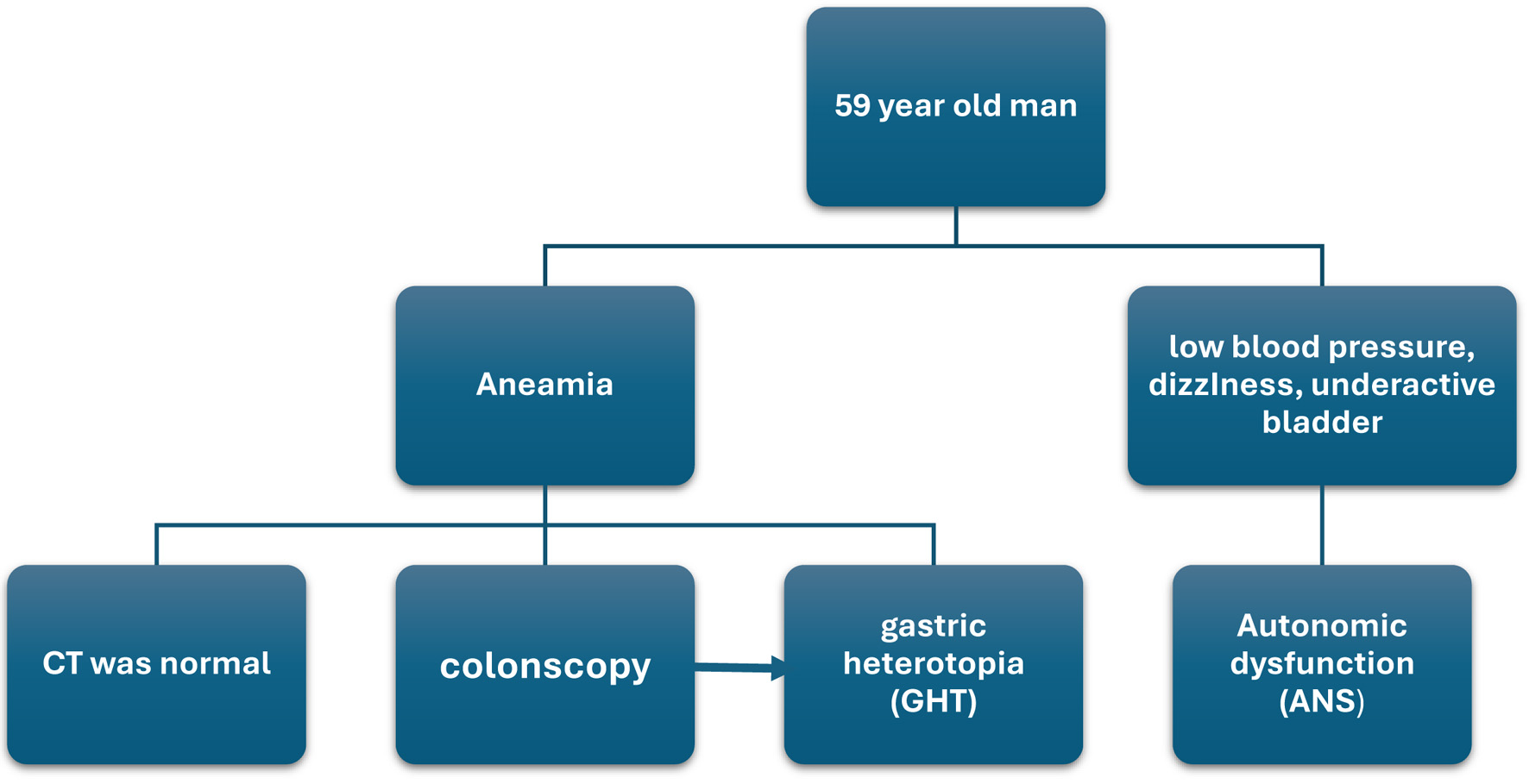

Figure 3 represents a schematic diagram showing the sequence of events in the diagnosis of the patient, who initially presented with anemia and was later found to have dizziness. A CT CAP was performed. The figure can be further explained in the context of the findings presented in Figures 1 and 2.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Summary of steps in the diagnosis. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case report explores a possible link between GHT and ANS dysfunction. Both conditions are rare individually, and there are no prior reports linking them together. Given the concurrent onset of symptoms and diagnoses, it is hypothesized that they may share a common embryological origin. The development of GHT originates from improper differentiation of endodermal tissue, while ANS dysfunction can arise from abnormal neural crest cell differentiation. Their concurrent presentation in this patient raises the question if the two conditions have a common embryological origin. Although GHT arises from endodermal tissue, it may interact secondarily with neural crest cells through inflammation, abnormal neurochemical signaling, or a yet to be defined process.

GHT is believed to occur due to errors in the differentiation of pluripotent endodermal stem cells in the intestinal lining, which may mistakenly form gastric mucosa. This could result from tissue injury or other unknown factors [10]. Another theory suggests that clusters of embryonic gastric tissue descend into the rectum, creating an ectopic patch, though this theory does not explain GHT in the hindgut [11]. A third theory proposes that GHT may develop following an unknown injury to the original tissue [12].

It is not yet established whether there is any association between GHT and ANS dysfunction, and therefore it is difficult to formulate further hypotheses regarding a potential link between the two. The following remains speculative: if such an association were to be confirmed, could it be due to abnormal migration of neural crest cells, as seen in Hirschsprung disease (HD) [13, 14], or due to progressive neuronal degeneration, as in familial dysautonomia [15, 16]?

While GHT and autonomic dysfunction have not previously been linked, further research is needed to determine whether these conditions share an embryological origin and whether this case represents a distinct syndrome or merely an incidental co-occurrence. Given that the patient in this report was diagnosed with both GHT and autonomic dysfunction at the age of 59, it is premature to suggest the existence of a unique syndrome. However, our case may pave the way for future reports of similar observations, which could, in turn, highlight the need to explore a possible connection between GHT and autonomic dysfunction and the potential for identifying rare or previously unrecognized syndromes.

Conclusions

This case may highlight a novel association between GHT and ANS dysfunction. GHT, though typically incidental, may be part of a broader clinical picture. Autonomic dysfunction should be explored in patients with unusual gastrointestinal symptoms. Rare combinations of findings may suggest developmental syndromes that have not yet been defined. Additional cases and potential investigations may help clarify the association.

Acknowledgments

Lana Alhalabi and Omar Alhalabi are both grateful for their parents for their unlimited support during their studies at Buckingham Medical School, UK.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and resources: MHA and AK; supervision and funding acquisition: MHA; methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, project administration, writing - original draft preparation, and writing - review and editing: all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Covington JD, Zong Y, Talat A, Strock C, Tomaszewicz K, Zivny J, Yang MX. Mass-forming gastric heterotopia of the rectum: a series of 3 cases from a single tertiary health center. Am J Case Rep. 2022;23:e936631.

doi pubmed - Borhan-Manesh F, Farnum JB. Heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper esophagus (inlet patch): A critical review. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1991;86(8):1024-1029.

- Gakiopoulou H, et al. Heterotopic gastric mucosa in the gallbladder: a report of two cases. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2001;46(1):140-143.

doi - Yahchouchy EK, Marano AF, Etienne JC, Fingerhut AL. Meckel's diverticulum. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192(5):658-662.

doi pubmed - Dinarvand P, Vareedayah AA, Phillips NJ, Hachem C, Lai J. Gastric heterotopia in rectum: A literature review and its diagnostic pitfall. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2017;5:2050313X17693968.

doi pubmed - Iacopini F, Gotoda T, Elisei W, Rigato P, Montagnese F, Saito Y, Costamagna G, et al. Heterotopic gastric mucosa in the anus and rectum: first case report of endoscopic submucosal dissection and systematic review. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2016;4(3):196-205.

doi pubmed - Ok CY, Akalina A. Gastric Heterotopia in the rectum. J Med Cases. 2012;3(2):113-115.

doi - Sanchez-Manso JC, Gujarathi R, Varacallo MA. Autonomic dysfunction. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) relationships with ineligible companies. 2025.

pubmed - Cleveland Clinic (n.d.) Dysautonomia: What It Is, Symptoms, Types & Treatment. Cleveland Clinic. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/6004-dysautonomia (Accessed: April 22, 2025).

- Murray FE, Lombard M, Dervan P, Fitzgerald RJ, Crowe J. Bleeding from multifocal heterotopic gastric mucosa in the colon controlled by an H2 antagonist. Gut. 1988;29(6):848-851.

doi pubmed - Ko H, Park SY, Cha EJ, Sohn JS. Colonic adenocarcinoma arising from gastric heterotopia: a case study. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47(3):289-292.

doi pubmed - Ming SC, Simon M, Tandon BN. Gross gastric metaplasia of ileum after regional enteritis. Gastroenterology. 1963;44(1):63-68.

doi - Espinosa R, Alonso Calderon JL. [Neural crest disorders and Hirschsprung's disease]. Cir Pediatr. 2009;22(1):25-28.

pubmed - Lotfollahzadeh S, Taherian M, Anand S. Hirschsprung disease. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) with ineligible companies. 2025.

pubmed - Bar-Aluma BE. Familial Dysautonomia. 2003 Jan 21 [Updated Nov 4, 2021]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1180/.

- Axelrod FB, Goldberg JD, Ye XY, Maayan C. Survival in familial dysautonomia: impact of early intervention. J Pediatr. 2002;141(4):518-523.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.