| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 11, November 2025, pages 427-433

Histoplasmosis-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in the Setting of Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis

S. Tahira Shah Naqvia, d, Jonathan Shakesprereb, Grant Wojdylab, Nolan Holleyb, Cara Randallc, Ion Prisneacc, Danish Safia

aDivision of Hematology & Oncology, Department of Medicine, West Virginia University, PO Box 9162, Morgantown, WV 26506-9162, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, West Virginia University, PO Box 9156, Morgantown, WV 26506-9156, USA

cDepartment of Pathology, Anatomy & Laboratory Medicine, West Virginia University, PO Box 9203, Morgantown, WV 26506-9203, USA

dCorresponding Author: S. Tahira Shah Naqvi, Division of Hematology & Oncology, Department of Medicine, West Virginia University, PO Box 9162, Morgantown, WV 26506-9162, USA

Manuscript submitted April 7, 2025, accepted August 26, 2025, published online October 31, 2025

Short title: Histoplasmosis-Induced HLH in GPA

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5126

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an aggressive and potentially life-threatening syndrome of aberrant immune hyperactivation characterized by excess cytokine release due to abnormal cytotoxic T-cell and macrophage activation. Secondary, or acquired, HLH occurs in the setting of underlying infection, malignancy, or autoimmune processes and often presents with systemic symptoms and multi-organ dysfunction that can initially be misattributed to infection, leading to a delay in diagnosis and management. Histoplasmosis-associated HLH is an infrequently described manifestation of secondary HLH that can occur in the setting of immunocompromised states. A 67-year-old woman with a history of granulomatosis with polyangiitis on active mycophenolate mofetil treatment initially presented with persistent flu-like symptoms in the setting of pancytopenia and elevated liver enzymes. Despite appropriate sepsis evaluation and extensive antimicrobial treatment, she remained persistently febrile and developed acute respiratory failure. Lab work revealed severely abnormal coagulation factors, hypofibrinogenemia, hyperferritinemia, and hypertriglyceridemia concerning for underlying hematologic disease process. Bone marrow biopsy obtained showed a hypercellular marrow with histiocytosis and hemophagocytic forms as well as intracellular narrow-based budding yeast, confirming an HLH diagnosis and suggestive of disseminated histoplasmosis. She was subsequently started on a high-dose steroid taper, intravenous immunoglobulin, and anti-fungal therapy with clinical improvement and stabilization of blood counts. Post-discharge follow-up has not involved repeat hospitalizations. Diagnosing HLH requires consideration of both clinical and laboratory criteria but there remains a lack of consensus use, especially in adult patients and those with associated autoimmune disease. Furthermore, the clinical presentation of HLH can overlap significantly with sepsis or other acute illnesses, thus delaying timely diagnosis and interventions for optimal patient outcomes. Our case emphasizes the importance of early consideration and comprehensive evaluation in this setting for HLH and secondary causes, including fungal etiologies. Additional clinical reporting of this rare presentation can increase clinician recognition and highlight potential diagnostic and treatment approaches. Subsequent close clinical observation with serial examinations and biochemical marker follow-up are needed to assess response and evaluate for changes in treatment approach.

Keywords: Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; Disseminated histoplasmosis; Granulomatosis with polyangiitis; Immunosuppressive therapy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening disease characterized by abnormal immune system activation resulting in tissue damage and organ dysfunction [1]. While predominantly affecting the pediatric patient population, cases of HLH in adults are frequently reported. Primary HLH occurs in the setting of genetic syndromes, whereas secondary HLH suggests disease caused by external or developed insults such as infection, autoimmune disease, malignancy, and organ transplant [2]. Histoplasmosis-associated HLH is a rare manifestation of secondary HLH and typically occurs in the setting of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), solid-organ transplant, chemotherapy, and immunosuppressive therapy [3].

The North American Consortium for Histiocytosis (NACHO) defines HLH as a syndrome identified by the fulfillment of diagnostic criteria (HLH-2004 or HLH-2009) and further classifies it as HLH disease when driven by immune dysregulation, or HLH disease mimics if similar clinical features arise without hallmark HLH pathophysiology such as sepsis or macrophage activation secondary to infection alone [2, 4].

Patients with HLH typically present with febrile illness with laboratory studies identifying multi-organ dysfunction [5]. Taken together, this clinical picture is often mistaken for sepsis, leading to a delay in diagnosis and management. Interestingly, infections are a well-recognized trigger of HLH, particularly viral and fungal pathogens, most commonly in immunocompromised patients [3]. Therefore, HLH provides clinicians with an ongoing clinical challenge given that expeditious identification and treatment are paramount for optimal outcomes.

Here, we present a case of disseminated histoplasmosis-associated HLH in a woman with a history of well-controlled granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) on immunosuppressive therapy. This case underscores the importance of early recognition and comprehensive evaluation for HLH in patient with persistent systemic symptoms despite standard antimicrobial therapy.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 67-year-old woman with a history of GPA diagnosed 4 years prior with pulmonary and renal manifestations of disease and a positive proteinase 3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) presented to her primary care provider with persistent fevers, chills, fatigue, and body aches. Her GPA had been well controlled with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF, 1,000 mg twice daily) and prednisone (10 mg daily). Her social history was negative for occupational or environmental exposures. Her family history was unremarkable for autoimmune diseases or malignancies.

Despite empiric treatment with azithromycin and holding of MMF for a presumed bacterial respiratory infection, her symptoms continued to worsen prompting her to present to the local emergency department. She presented febrile to 39.7 °C. Laboratory findings were significant for pancytopenia with a white blood cell count (WBC) 2.1 × 109/L (reference range: 4.0 - 11.0 × 109/L), hemoglobin 9.6 g/dL (reference range: 12.0 - 16.0 g/dL), and platelet count 71 × 109/L (reference range: 150 - 450 × 109/L) and mildly elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase 53 U/L (reference range: 10 - 40 U/L), alanine aminotransferase 37 U/L (reference range: 7 - 56 U/L)). Imaging showed splenomegaly and possible enteritis. Empiric vancomycin and cefepime were started to treat sepsis of unknown origin, but blood, sputum, and stool cultures remained negative.

Her condition deteriorated with new-onset atrial fibrillation and hypoxic respiratory failure. Computed tomography (CT) of chest showed bilateral pleural effusion and pericardial effusion development. Thoracentesis revealed transudative fluid and echocardiography showed normal cardiac function. Infectious Disease recommended broadening antimicrobial coverage to vancomycin, meropenem, and micafungin. Despite this, she remained febrile and critically ill.

Rheumatology was consulted for concern of GPA flare and recommended pulse-dose methylprednisolone followed by high-dose prednisone 60 mg daily, although no definitive flare could be identified. After 14 days of antimicrobials and steroids without improvement, additional laboratory studies showed unmeasurably elevated prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratio (INR). She had hypofibrinogenemia of < 5 g/L (reference range: 200 - 400 mg/dL), hyperferritinemia of 12,700 µg/L (reference range: 13 - 150 µg/L), and hypertriglyceridemia of 2.73 mmol/L (reference range: < 1.7 mmol/L). A serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL2R) level was obtained and she was transferred to our tertiary care center.

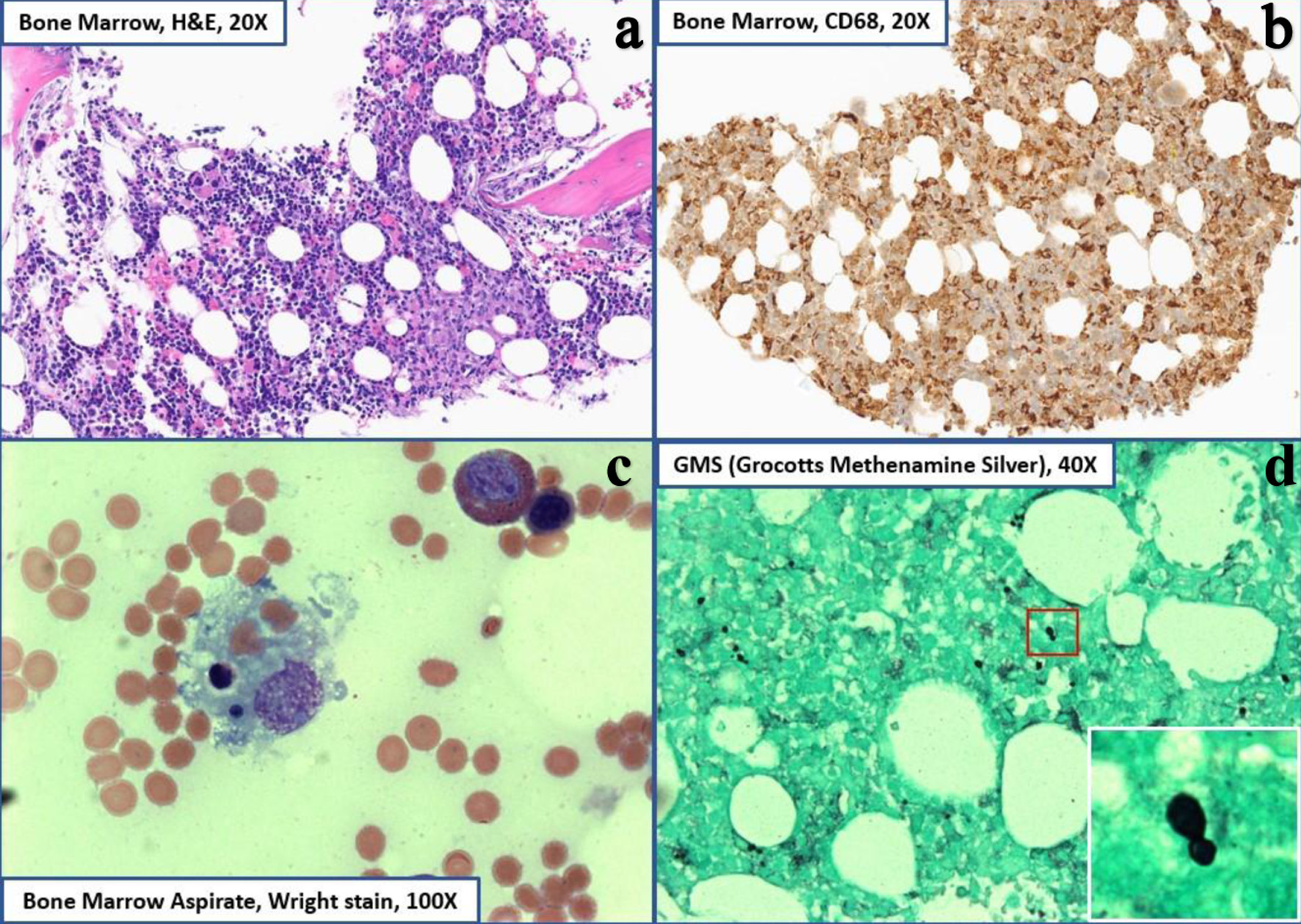

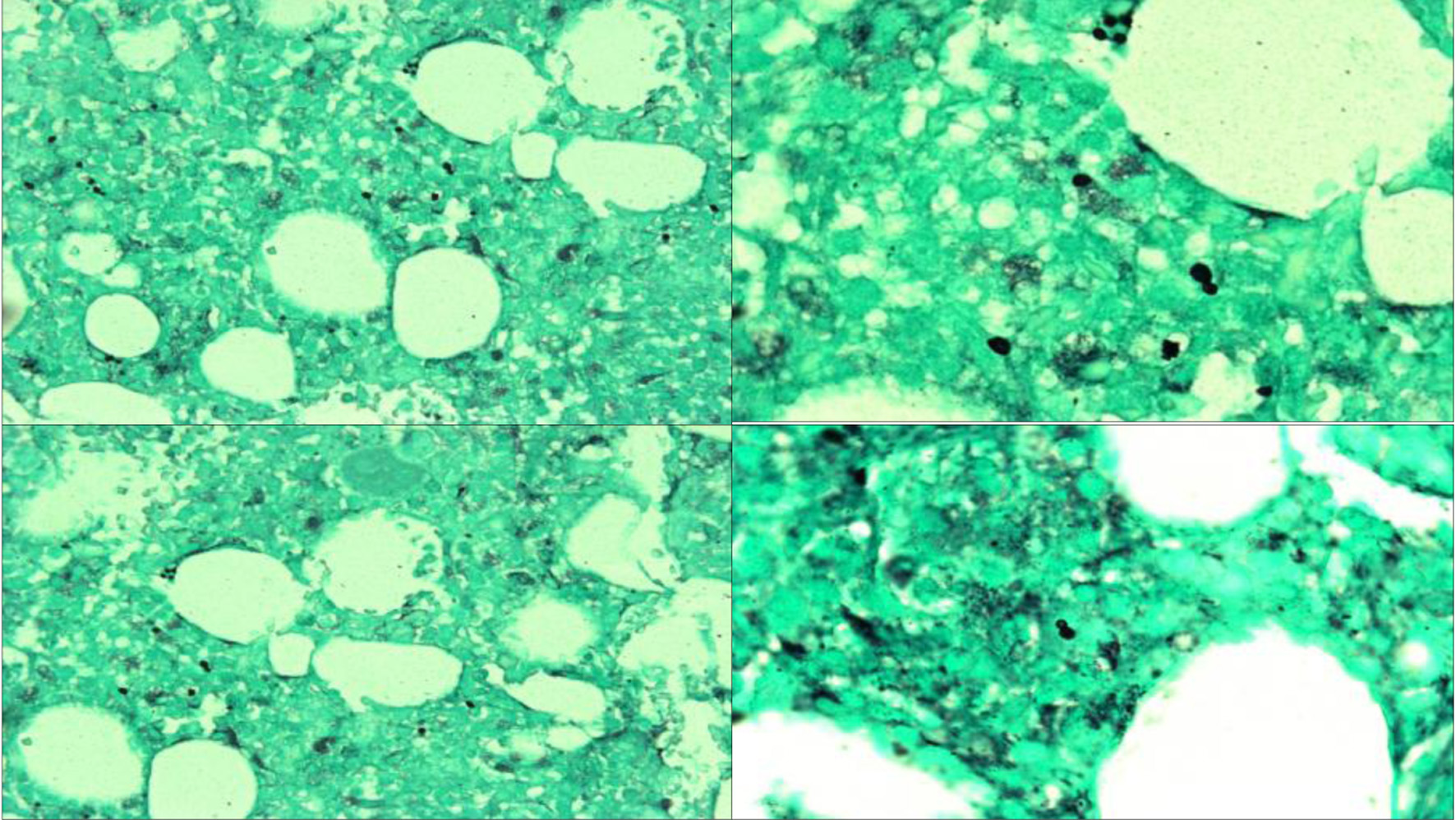

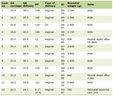

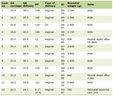

Upon arrival, Infectious Diseases discontinued antimicrobials, given that the patient had not had improvement after 2 weeks, and ordered a (1-3)-β-D-glucan (Fungitell) test. Hematology and Oncology were consulted for concern of HLH given persistent fever, cytopenias, coagulopathy, elevated ferritin, and hypertriglyceridemia. Bone marrow biopsy histopathology (Fig. 1) showed hypercellular bone marrow with histiocytosis and occasional hemophagocytic forms (Fig. 2) as well as intracellular narrow-based budding yeast (Fig. 3), consistent with HLH and suggestive of disseminated histoplasmosis. A positive Fungitell later confirmed systemic fungal infection and sIL2R was markedly elevated at 10,324 U/mL (reference range: < 1,033 U/mL), fulfilling HLH-2004 criteria [4] (Table 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Bone marrow core biopsy histopathology. (a) H&E staining at × 20 magnification showing hypercellular marrow (60% cellularity). (b) CD68 staining diffusely positive showing histiocytosis (right upper). (c) Wright-Giemsa staining at × 100 magnification showing erythrophagocytic forms and hemophagocytic forms with ingested leukocytes (lower left). (d) GMS staining showing narrow-based budding yeasts consistent with histoplasma capsulatum (right lower). GMS: Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver; H&E: hematoxylin and eosin. |

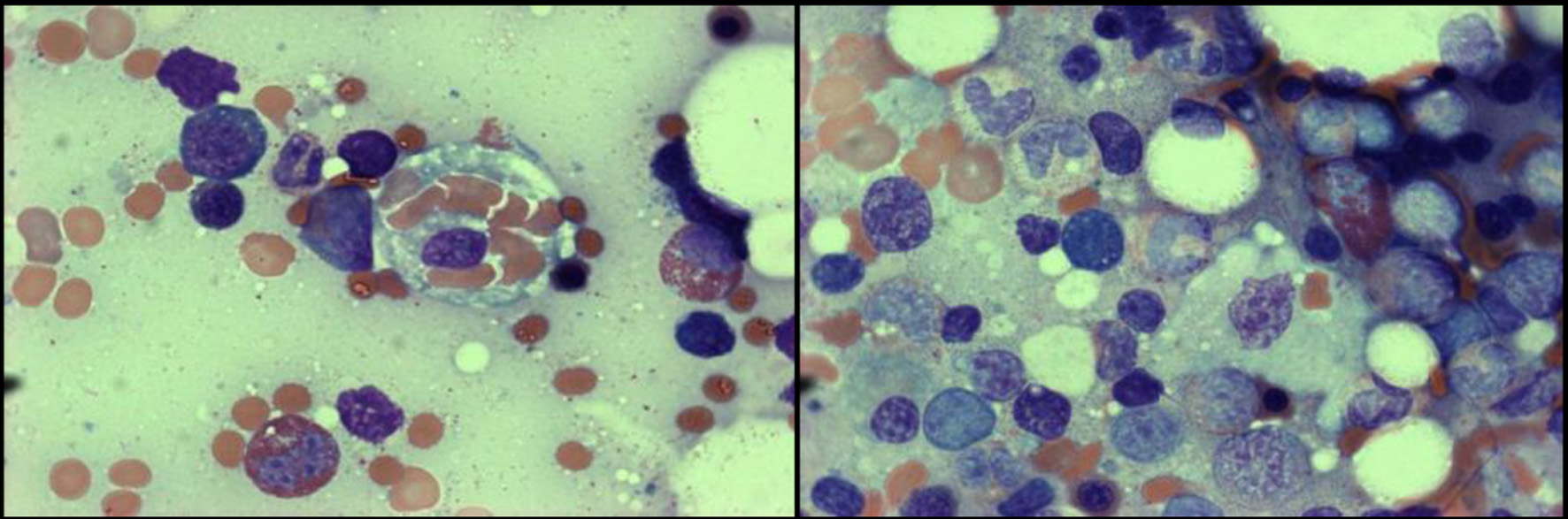

Click for large image | Figure 2. Wright-Giemsa stain at × 200 (left) and × 1,000 (right) magnification showing a single histiocyte performing hemophagocytosis with ingestion of mature RBCs. RBCs: red blood cells. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. GMS staining at × 40 (upper left, lower left) and × 100 (upper right, lower right) showing numerous extracellular small narrow-based yeast cells consistent with disseminated histoplasmosis. GMS: Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver. |

Click to view | Table 1. HLH-2004 Diagnostic Criteria and Patient Findings |

She was treated with a high-dose dexamethasone taper (initial dose 18.5 mg daily), intravenous immunoglobulin (25 g daily for 5 days), and liposomal amphotericin B (3 mg/kg daily for 1 week), and then transitioned to itraconazole 200 mg for planned 1 year. MMF was indefinitely discontinued.

At discharge, her blood counts improved to WBC 2.8 × 109/L, hemoglobin 8.5 g/dL, and platelets 87 × 109/L, and returned to baseline oxygen requirements. Table 2 shows the key laboratory findings over hospital course. At 1-month Infectious Disease follow-up, itraconazole was discontinued due to transaminitis and isavuconazole was started with a loading dose of 372 mg every 8 h for six doses, followed by maintenance 372 mg daily. She ultimately completed her steroid taper with downtrending ferritin and sIL2R levels. At 6-month Hematology and Oncology follow-up, she remained ambulatory and clinically stable, requiring intermittent transfusions for anemia without further hospitalizations.

Click to view | Table 2. Key Laboratory Findings Over Hospital Course |

| Discussion and conclusions | ▴Top |

This case highlights a novel clinical presentation of HLH triggered by disseminated histoplasmosis in a patient with a history of well-controlled GPA on active immunosuppressive therapy. HLH is a syndrome with significant diagnostic and clinical complexity; however, its overlap with sepsis and autoimmune diseases - especially in the adult populations - further confounds timely diagnosis and intervention. To date, there are limited reports describing disseminated histoplasmosis-associated HLH in the context of GPA. This case underscores the importance of evaluating for opportunistic infections in patients with suspected HLH, especially in those with autoimmune disorders on immunosuppressants, and when standard antimicrobial therapies fail; as well as to emphasize the need for increased clinical vigilance for this uncommon, yet life-threatening, condition.

HLH is a rare severe hyperinflammatory condition characterized by excess cytokine release due to abnormal cytotoxic T-cell and macrophage activation. Clinically, it can be classified as primary (familial) in the setting of inherited genetic mutations driving innate cytotoxic dysfunction or secondary (acquired) due to underlying infection, malignancy, autoimmune, or autoinflammatory processes [6].

Primary HLH is an autosomal recessive-inherited syndrome manifested in the first years of life. Familial HLH is associated with homozygous mutations in genes responsible for cytotoxic T lymphocyte and natural killer (NK) cell-mediated target binding and apoptosis. Mutations in PRF1, UNC13-D, STX11, STXBP2, as well as in the RAB27A, LYST, SH2D1A genes associated with X-linked congenital immunodeficiency syndromes, result in impaired cytotoxic immune function characterized by excess interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-led macrophage activation and proinflammatory cytokine production [7].

Secondary, or acquired, HLH typically occurs at an older age, with greater clinical heterogeneity, and without associated familial history in the context of underlying disease. Infection is understood to be the most common trigger of secondary HLH [8]. Persistent systemic symptoms can initially be misattributed to sepsis or bacteremia; a lack of improvement despite indicated antimicrobial treatment or identifiable source of infection can indicate underlying HLH in such scenarios [9]. This chronologic heterogeneity of presentation as well as the overlapping features with severe infection can obfuscate timely HLH diagnosis and delay prompt treatment.

The diagnosis of HLH requires consideration of a constellation of clinical and laboratory findings as no single clinical or laboratory parameter has adequate sensitivity and specificity to be diagnostic. The HLH-2004 criteria, as established by the Histiocyte Society, allows for diagnosis in one of two ways: 1) identification of a known HLH-associated genetic mutation, or 2) fulfillment of at least five out of eight diagnostic criteria. These eight criteria include: 1) persistent fever ≥ 38.3 °C, 2) splenomegaly, 3) cytopenias affecting at least two of three lineages in the peripheral blood (hemoglobin < 90 g/L, platelets < 100 × 109/L, neutrophils < 1.0 × 109/L), 4) hypertriglyceridemia (fasting triglycerides ≥ 265 mg/dL) and/or hypofibrinogenemia (fibrinogen ≤ 1.5 g/L), 5) hemophagocytosis identified on bone marrow, spleen, or lymph node biopsy in the absence of malignancy, 6) decreased or absent NK cell activity, 7) hyperferritinemia (ferritin ≥ 500 µg/L), and 8) an elevated sIL2R (≥ 2,400 U/mL) [4].

Additional associated findings that may support the diagnosis, though are not part of the HLH-2004 criteria, include neurologic dysfunction, rash, respiratory failure, transaminitis, coagulopathy, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The care of adult patients meeting such criteria, however, can be challenging due to its characterization from pediatric clinical trials and a lack of consensus use. Additionally, patient-specific considerations including age, immunocompromised status, and co-morbidities must be considered in practical application [10]. Therefore, a high degree of suspicion is warranted for HLH in adult patients with a clinical syndrome compatible with critical illness that does not improve despite standard of care treatment.

With a non-specific presentation suggestive of infection, the initial concern in our patient was for acute bacterial infection and treatment was centered on antimicrobial therapy due to her immunocompromised state. Furthermore, suspicion was held for acute flare of her chronic autoimmune condition and steroid therapy was expected to alleviate an active inflammatory process. A subsequent lack of improvement and the development of high-grade fevers, hepatobiliary dysfunction, and acute respiratory failure with bilateral pleural effusions highlighted a progression of illness severity despite appropriate sepsis treatment.

The development of pancytopenia alongside elevated ferritin and triglycerides was concerning for HLH versus disseminated intravascular coagulation with the presence of abnormal coagulation factors and severely low fibrinogen. Bone marrow evaluation with the ultimate identification of hemophagocytic forms along with intracellular narrow-based budding yeast cells confirmed invasive histoplasmosis infection with concomitant secondary HLH [11]. An elevated sIL2R level > 10,000 pg/mL further substantiated this. Subsequent treatment with IVIG and an extended course steroid taper along with systemic antifungal therapy medications resulted in count recovery, stabilization of respiratory status, and resolution of fevers.

Our patient presented with a history of chronic rheumatic disease in the form of GPA on immunosuppressive therapy with MMF. There is overall limited reporting on HLH cases with associated GPA. Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is a rare condition of secondary HLH associated with autoimmune disorders best characterized in children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis but also noted in adults with Still’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, etc. [12]. MAS can develop either due to immune dysfunction caused by the underlying rheumatic disease or triggered by infection or immunosuppression. There are no established criteria for diagnosis of MAS and, due to clinical overlap with HLH, it is often identified using similar clinical and biomarker features [13].

With a history of GPA on MMF therapy, it can be reasonably presumed that our patient would be at higher risk of developing a severe infection, including fungal, as compared to an immunocompetent individual. With infection as the triggering agent of HLH, immunosuppression in this context may have contributed to immune dysregulation leading to excess cytokine production. It is possible that our patient’s previous treatment may have contributed to a loss of negative feedback in antigen presentation and/or cytokine production in the presence of disseminated histoplasmosis.

Previous studies have described the occurrence of invasive fungal infections in systemic immunocompromised states, including HIV, but rarely in the context of autoimmune disease with associated HLH [14]. The mechanism of histoplasmosis-triggered HLH is not clearly elucidated. However, it is suspected that macrophage phagocytosis of yeast cells results in T helper 1 (Th1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)-mediated activation of cytotoxic T cells and NK cells [15]. However, due to defective regulatory signaling, unregulated cytokine release including IL-10, IL-1, IL-6, IFN-γ, and TNF-α leads to tissue damage with a positive feedback loop of macrophage hyperstimulation and systemic inflammation accompanied by fever, myelosuppression, endothelial damage, and coagulopathy [16]. IL2R, a heterotrimeric transmembrane protein, is upregulated on immune activated T cells; thus, high sIL2R levels are found in hemophagocytic syndromes as well as other conditions associated with T-cell activation and have been established as a key component in disease severity and monitoring of hyperinflammatory syndromes, such as HLH [17]. sIL2R is a valuable supportive biomarker in HLH as well as being useful in monitoring therapeutic response; however, it cannot be used alone given its lack of specificity, limited availability, long turnaround time, and lack of consistent correlation with clinical severity or prognosis [17]. We suspect that HLH in our patient could have been triggered by excess antigen presentation or cytokine release due to a disseminated fungal infection.

Current treatment recommendations for primary HLH patients entails chemo-immunotherapy followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [10]. There is a lack of consensus approach to HLH due to underlying infection or with associated autoimmune disease in the currently accepted HLH-2004 paradigm [18]. Furthermore, assessment with these criteria can be difficult due to the heterogeneous clinical presentation of secondary HLH in the setting of acute illness and potentially delay critical treatment. In our case, recognition of the patient’s rheumatologic disease history as well as the presence of an acute fungal infection dictated the prompt use of combined immunosuppressive and anti-microbial treatment rather than frontline chemo-immunotherapy. This treatment approach ultimately resulted in clinical improvement of the patient. This suggests consideration of and a comprehensive evaluation for secondary causes prior to treatment initiation, including fungal etiologies. Subsequent close clinical observation with serial examinations and biochemical marker follow-up are needed to assess response and evaluate for changes in treatment approach.

Learning points

HLH is an aggressive and life-threatening syndrome of immune dysregulation that is challenging to diagnose due to significant overlap with sepsis and other acute illnesses.

Early consideration of and evaluation for HLH and secondary causes, especially in the patients with autoimmune disorders on chronic immunosuppressants, are essential for improved clinical outcomes.

Persistent fever, organomegaly, cytopenias, and elevated inflammatory markers (e.g., ferritin, triglycerides, and sIL2R) without improvement on standard therapies should prompt consideration of HLH.

Disseminated histoplasmosis is a rare but important infectious trigger of secondary HLH, particularly in immunocompromised patients, even in the absence of clear environmental exposure history.

Treatment of secondary HLH requires addressing the underlying condition; in this case, combined antifungal therapy and immunomodulation led to clinical recovery without the need for chemo-immunotherapy agents.

Close follow-up with serial labs and clinical reassessment is necessary to evaluate therapeutic response and guide treatment adjustments in HLH cases.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

No grants, fellowships, or gifts of materials to disclose.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been obtained.

Author Contributions

JS assisted in literature review, manuscript writing, and project submission. GW assisted with manuscript writing. NH assisted with literature review and manuscript writing. TN assisted with project design and development, manuscript review, and figure preparation. CR and IP were responsible for pathologic review, interpretation, and figure preparation. DS provided project guidance and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

GPA: granulomatosis with polyangiitis; HLH: hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; IL: interleukin; IL2R: interleukin-2 receptor; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; MAS: macrophage activation syndrome; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; sIL2R: serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor; Th1: T helper 1; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha

| References | ▴Top |

- Filipovich A, McClain K, Grom A. Histiocytic disorders: recent insights into pathophysiology and practical guidelines. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(1 Suppl):S82-89.

doi pubmed - Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, Filipovich AH, McClain KL. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2011;118(15):4041-4052.

doi pubmed - Jabr R, El Atrouni W, Male HJ, Hammoud KA. Histoplasmosis-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: A Review of the Literature. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2019;2019:7107326.

doi pubmed - Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131.

doi pubmed - Bergsten E, Horne A, Arico M, Astigarraga I, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Ishii E, et al. Confirmed efficacy of etoposide and dexamethasone in HLH treatment: long-term results of the cooperative HLH-2004 study. Blood. 2017;130(25):2728-2738.

doi pubmed - Kleynberg RL, Schiller GJ. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: an update on diagnosis and therapy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2012;10(11):726-732.

pubmed - Gupta S, Weitzman S. Primary and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: clinical features, pathogenesis and therapy. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6(1):137-154.

doi pubmed - Janka GE, Lehmberg K. Hemophagocytic syndromes—an update. Blood Rev. 2014;28(4):135-142.

doi pubmed - Machowicz R, Janka G, Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W. Similar but not the same: differential diagnosis of HLH and sepsis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;114:1-12.

doi pubmed - La Rosee P, Horne A, Hines M, von Bahr Greenwood T, Machowicz R, Berliner N, Birndt S, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133(23):2465-2477.

doi pubmed - Kikuchi A, Singh K, Gars E, Ohgami RS. Pathology updates and diagnostic approaches to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Diagnostic Histopathology. 2023;29(5):237-245.

- Kumar B, Aleem S, Saleh H, Petts J, Ballas ZK. A personalized diagnostic and treatment approach for macrophage activation syndrome and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. J Clin Immunol. 2017;37(7):638-643.

doi pubmed - Griffin G, Shenoi S, Hughes GC. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020;34(4):101515.

doi pubmed - Townsend JL, Shanbhag S, Hancock J, Bowman K, Nijhawan AE. Histoplasmosis-induced hemophagocytic syndrome: a case series and review of the literature. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2(2):ofv055.

doi pubmed - Creput C, Galicier L, Buyse S, Azoulay E. Understanding organ dysfunction in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(7):1177-1187.

doi pubmed - Cron RQ, Goyal G, Chatham WW. Cytokine storm syndrome. Annu Rev Med. 2023;74:321-337.

doi pubmed - Nguyen TH, Kumar D, Prince C, Martini D, Grunwell JR, Lawrence T, Whitely T, et al. Frequency of HLA-DR(+)CD38(hi) T cells identifies and quantifies T-cell activation in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, hyperinflammation, and immune regulatory disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;153(1):309-319.

doi pubmed - Naymagon L. Can we truly diagnose adult secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)? A critical review of current paradigms. Pathol Res Pract. 2021;218:153321.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.