| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 1, January 2025, pages 17-22

Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia Syndrome With Aortic Stenosis: A Twist on Heyde Syndrome?

Lefika Bathobakaea, e , Noman Khalida, Sacide S. Ozgura, Devina Adaljaa, Rajkumar Doshib, Gabriel Melkic, Kamal Amerc, Yana Cavanaghc, d, Walid Baddourac

aInternal Medicine, St. Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson, NJ, USA

bCardiology, St. Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson, NJ, USA

cGastroenterology and Hepatology, St. Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson, NJ, USA

dInterventional and Therapeutic Endoscopy, St. Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson, NJ, USA

eCorresponding Author: Lefika Bathobakae, Internal Medicine, St. Joseph’s University Medical Center, Paterson, NJ 07503, USA

Manuscript submitted July 21, 2024, accepted November 4, 2024, published online December 21, 2024

Short title: Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia Syndrome With AS

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc4311

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Heyde syndrome is a triad of aortic stenosis (AS), gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding from angiodysplasia, and acquired von Willebrand disease (vWD). It is hypothesized that stenotic aortic valves cleave von Willebrand factor (vWF) multimers, predisposing patients to bleeding from GI angiodysplasias. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that aortic valve replacement often leads to the resolution of GI bleeding. Heyde syndrome is typically described in the context of AS and small bowel angiodysplasias (Dieulafoy’s lesion, intestinal vascular malformation, and arteriovenous malformations). However, data on AS and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) association are scarce. GAVE is a vascular anomaly characterized by ectatic capillaries, arterioles, and venules, which can lead to upper GI bleeding. The paucity of data on GAVE-AS association may lead to underdiagnosis and/or under-reporting. Herein, we describe two cases of GAVE-AS that were diagnosed and treated at our institution. This case series focuses on patient presentations and clinical outcomes and aims to raise awareness about this rare association.

Keywords: Heyde syndrome; Aortic stenosis; Gastrointestinal angiodysplasia; Gastric antral vascular ectasia; Aortic valve replacement

| Introduction | ▴Top |

In 1958, Edward C. Heyde, an American internist, described a unique association between gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and aortic stenosis (AS) [1, 2]. Over a decade, Dr. Heyde had treated at least 10 geriatric patients with this phenomenon and was intrigued [1, 3]. To date, more case reports have been published describing this association (Heyde syndrome), but its definition, epidemiology, and etiopathogenesis remain contested and controversial [4]. A retrospective review of the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2007 through 2014 revealed a 3.1% period prevalence of intestinal angiodysplasia-associated GI bleeding with AS (Heyde syndrome) [5].

Heyde syndrome is a rare clinical entity that signifies an association between GI bleeding from GI angiodysplasias and AS [1, 2, 6, 7]. It has been postulated that stenosed aortic valves break down the von Willebrand factor (vWF) complexes, leading to an acquired von Willebrand syndrome (AVWS) and lower GI bleeding [2, 3, 6]. The exact incidence and prevalence of Heyde syndrome are unknown due to a lack of clear diagnostic criteria and an evolving definition [8]. As most GI angiodysplasias (Dieulafoy’s lesion, intestinal vascular malformation, and arteriovenous malformations) arise from the small bowel and colon [6], Heyde syndrome is typically defined in that context. Data on gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), a rare cause of non-variceal GI bleeding and AS, are scarce [9].

Herein, we describe a case series of Heyde syndrome with GI bleeding due to a gastric source (GAVE), along with outcomes and discussion on why this finding may be underdiagnosed.

| Case Reports | ▴Top |

Case 1

A 72-year-old woman with a medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease (CAD) was referred to the emergency department (ED) by her primary care doctor for evaluation of low hemoglobin levels. The patient’s hemoglobin level steadily decreased over 2 months. She had undergone cardiac catheterization in the past; however, no stent was placed, and she was not on any anti-coagulant medications. The patient had a colonoscopy 2 months prior to this encounter, which was reportedly normal, and an upper endoscopy, which showed gastritis and nonbleeding gastric ulcers. She denied experiencing nausea, hematemesis, abdominal pain, diarrhea, changes in stool caliber, melena, hematochezia, or tenesmus, and her vital signs were normal. On examination, she had a soft, obese abdomen that was not tender on palpation. Digital rectal examination was negative for bleeding, hemorrhoids, and palpable masses. A cardiovascular examination revealed a 2/6 systolic ejection murmur at the right upper sternal border.

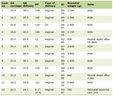

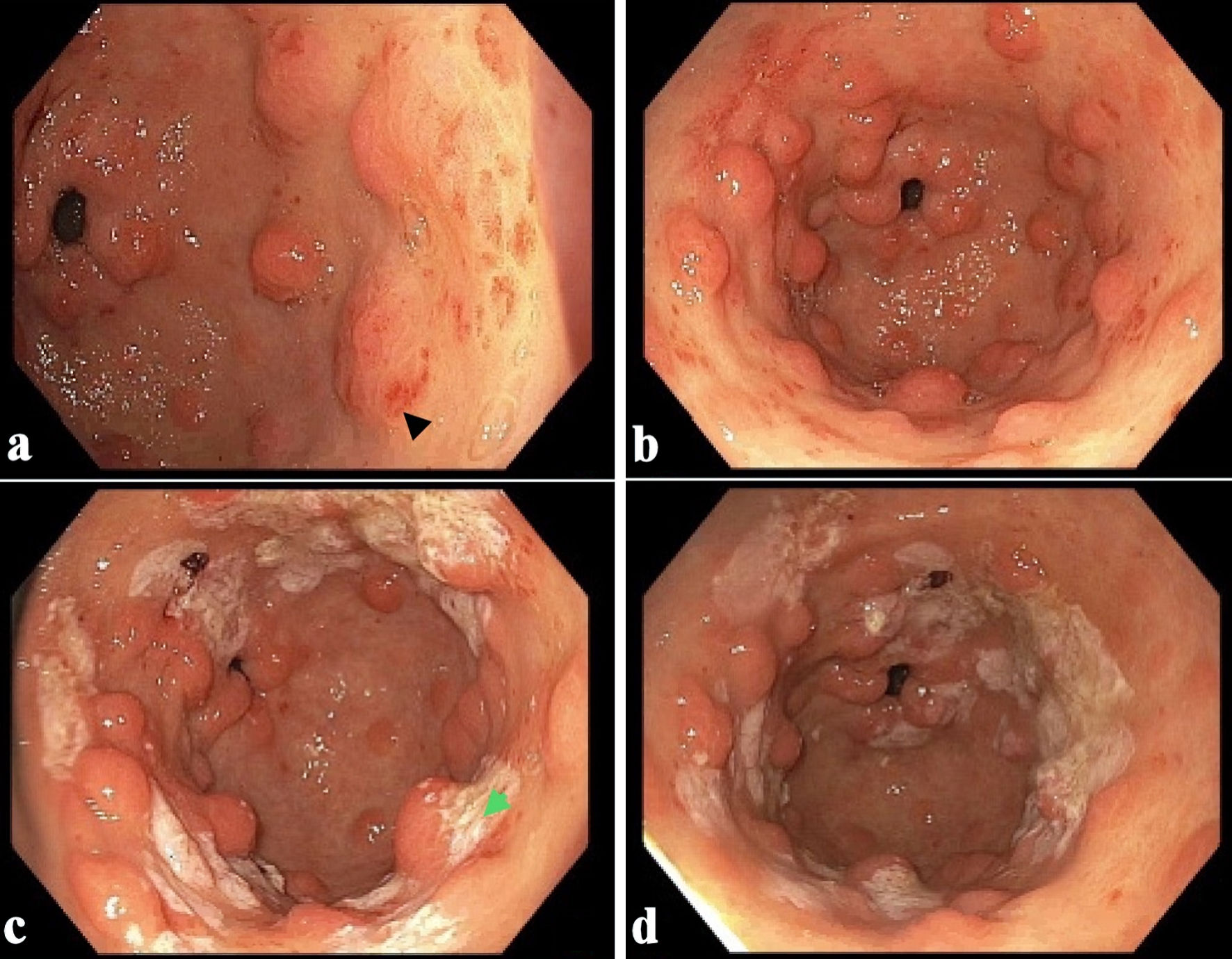

Triage blood tests showed low hemoglobin level (5.7 g/dL), hypochromic microcytic anemia, elevated creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen (Table 1). The patient was admitted for symptomatic anemia and received two units of packed red blood cells (PRBCs). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed GAVE with bleeding that was successfully treated with argon plasma coagulation (APC) (Fig. 1). She additionally underwent a colonoscopy, which identified a 6 mm polyp that was removed with a cold snare, and the pathology revealed a tubular adenoma.

Click to view | Table 1. Pertinent Admission Laboratory Results for Cases 1 and 2 |

Click for large image | Figure 1. An endoscopic image showing gastric antral vascular ectasia in the gastric antrum with spontaneous bleeding (black arrow) requiring argon plasma coagulation (green arrow). |

An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed normal sinus rhythm, minimal voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy, and a septal infarct of undetermined age. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) demonstrated a normal left ventricular ejection fraction of 55-60%, hypertensive cardiomyopathy, and moderate-to-severe aortic valve stenosis (aortic valve area (AVA): 0.93 cm2, mean pressure gradient 19.5 mm Hg, and peak aortic velocity: 2.92 m/s). The patient’s hemoglobin level stabilized around 8.0 g/dL, and she was discharged with plans for a repeat EGD within 6 months as well as subsequent cardiac catheterization. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Case 2

An 87-year-old man with a medical history of GAVE syndrome and multiple hospitalizations due to recurrent episodes of GI bleeding presented to the ED for evaluation of generalized weakness and fatigue for 2 weeks. In the morning of the most recent ED visit, the patient experienced dark tarry stools and acute-onset epigastric pain. He denied fresh blood per rectum, nausea, vomiting, change in stool caliber, or recent weight loss. He was diagnosed with GAVE disease 2 years prior to this encounter and had undergone multiple EGDs with argon plasma coagulation and radiofrequency ablation (RFA), which resulted in temporary resolution of the bleeding diathesis. The patient’s medical history was also significant for CAD requiring coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG), which was complicated by postoperative atrial fibrillation. A 2017 TTE revealed severe global left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction: 25-30%), severe AS (AVA: 0.88 cm2, mean gradient: 32 mm Hg; peak aortic velocity: 3.9 m/s), and moderate aortic valve regurgitation. Similar findings were observed during cardiac catheterization, and the patient eventually underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in 2017. The hemoglobin level at the time of the procedure was 11.9 g/dL, and the patient denied having hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia.

At this visit, the patient’s vital signs were significant for elevated blood pressure (168/71 mm Hg) and tachycardia (105 beats per minute (bpm)). On physical examination, the patient was alert, awake and in no acute distress. Upon inspection, he had a well-healed sternotomy scar and a left-sided automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) pocket. A late systolic murmur was observed at the right lower sternal border, radiating to the apex of the heart. A digital rectal examination revealed external hemorrhoids and dark, soft stool. The patient had a normal rectal tone without fresh blood per rectum. Triage blood tests revealed pancytopenia (hemoglobin level: 7.4 g/dL, white blood cell count: 2.7 × 103/mm3, and platelet count: 104 × 103/mmm3), elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (Table 1). The patient’s baseline hemoglobin was 8-9 g/dL.

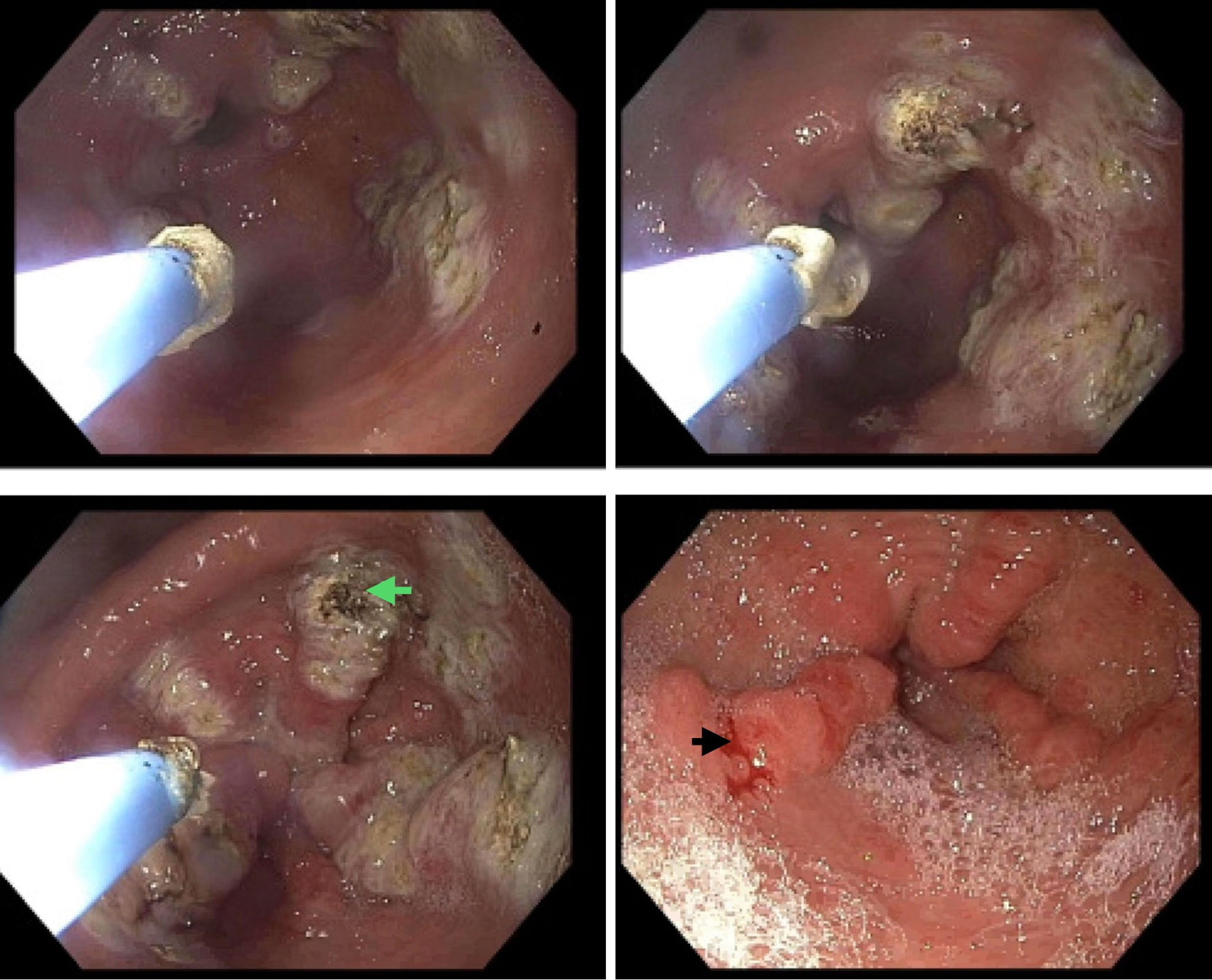

The patient was transfused with one unit of PRBCs to maintain a hemoglobin level above 8.0 g/L and administered pantoprazole 80 mg intravenous (IV) once. Clopidogrel and aspirin were discontinued to avert further bleeding episodes, and an EGD with APC was performed. EGD revealed a normal esophagus, severe nodular GAVE in the gastric antrum without bleeding, and a normal duodenum (Fig. 2). The patient was discharged without any bleeding episodes. A repeat EGD at the 2-week follow-up showed severe nodular GAVE without bleeding, and 12 bands were successfully placed. There was no bleeding at the end of the procedure. Six months have passed since endoscopic banding, and the patient remains asymptomatic with a stable hemoglobin level of 9.1 - 9.7 g/dL. A recent transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) showed a fully recovered ejection fraction and a normally functioning bioprosthetic aortic valve. There was no evidence of paravalvular leaks or significant pannus.

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a, b) Endoscopic images showing moderate nodular gastric antral vascular ectasia without bleeding (black arrow). (c, d) GAVE status post argon plasma coagulation (green arrow). GAVE: gastric antral vascular ectasia. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this case series, we share our experience in diagnosing and managing two older adults with Heyde syndrome, with GI bleeding due to GAVE. The patient described in case 1 presented with occult GI bleeding and was found to have GAVE on endoscopy. Given concurrent AS diagnosis, the patient met the diagnostic criteria for Heyde syndrome. The patient discussed in case 2 had refractory nodular GAVE requiring multiple endoscopic interventions, including APC, RFA, and endoscopic band ligation (EBL). Given a history of severe AS and TAVR, this patient’s presentation was also consistent with Heyde syndrome. Notably, AVWS was not tested for in either case as it is not necessary to establish a diagnosis. A systematic review of case reports showed no evidence of AVWS in 50/77 cases. vWF levels were normal in a fraction of the cases and not assessed in more than 50% of the reported cases. We submit that GAVE-AS is a subtype of Heyde syndrome worth investigating to ensure better patient outcomes.

Heyde syndrome is a disorder characterized by the co-occurrence of AS and GI bleeding due to angiodysplasia and is often associated with AVWS [6, 7]. The pathophysiology of Heyde syndrome remains a subject of investigation, with prevailing theories hypothesizing a cascade of events initiated by AS. The consequent reduction in high-molecular-weight vWF due to increased shear stress is considered a pivotal factor leading to bleeding from various manifestations of intestinal angiodysplasia [10]. vWF is a glycoprotein that plays a multifaceted role in hemostasis. It acts as a bridge for platelet adhesion and aggregation at the site of vascular injury, facilitating the initial stages of clot formation [6, 11]. vWF also acts as a chaperone for factor VIII, which protects it from degradation and ensures its appropriate distribution in the bloodstream [11]. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that aortic valve replacement (AVR) often leads to the resolution of GI bleeding and an increase in high-molecular-weight vWF multimers postoperatively [10, 11]. Another theory suggests that angiodysplasias may develop secondary to localized hypoxemia. In patients with AS, low cardiac output can result in decreased end-organ oxygenation, promoting the formation of these vascular malformations [2, 6, 12].

Although an association between AS and small-bowel angiodysplasias has been established, there are limited data on GAVE-AS. This form of Heyde syndrome has been under-studied and under-reported. First described in 1953, GAVE syndrome is a condition characterized by dilated and fragile blood vessels in the stomach lining [7, 13-15]. In 1984, a case of patient was reported with chronic GI bleeding and distinctive endoscopic findings of dilated blood vessels in the gastric antrum, further shedding light on this condition. Since then, more cases have been reported, especially in geriatric patients with cirrhosis, autoimmune disorders, and chronic kidney disease [13-15]. GAVE is estimated to account for 4% of all non-variceal bleeding, and 6% of upper GI bleeds in patients with underlying cirrhosis [14, 16]. Bleeding can range from occult bleeding to overt melena and hematemesis. Other symptoms may include epigastric discomfort, fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath due to iron-deficiency anemia [6, 9, 14, 16, 17]. In our series, the first patient presented with covert GI bleeding, whereas the second patient presented with symptomatic anemia and overt GI bleeding.

The first case of Heyde syndrome due to GAVE-AS involved an elderly male with a history of multiple hospitalizations for symptomatic anemia requiring multiple transfusions. An EGD revealed GAVE, and the AS was diagnosed on a TTE [18]. In a systematic review of case reports on Heyde syndrome, Saha et al [6] reported gastric vascular malformations as the source of bleeding in seven of the 74 reviewed cases; however, it is unclear what fraction of the seven patients had GAVE. A retrospective review of the NIS database from 2016 through 2019 revealed about 85,000 patients with a primary admission diagnosis of GAVE, with only 5,315 (6.2%) of the patients having a secondary diagnosis of AS [9]. Patients with AS were found to have a two-fold increased risk of developing GAVE, and patients with GAVE-AS had a higher risk of GI bleeding, ischemic heart disease, and increased healthcare utilization [9]. In our case series, the second patient had AS, which may have predisposed him to developing GAVE.

Diagnosing Heyde syndrome requires a combination of clinical, endoscopic, and laboratory investigations. Clinical features suggestive of Heyde syndrome include recurrent GI bleeding and cardiac symptoms. AS may present as syncope, angina, heart failure, or systolic ejection murmur, or pulsus parvus et tardus on physical examination. Easy bruisability, heavy menstrual periods, hematoma, or hemarthrosis may be suggestive of acquired von Willebrand disease (vWD) [6, 7, 10]. Initial laboratory workup may include a complete blood count, coagulation panel, complete metabolic panel, and fecal occult blood testing. Because patients with Heyde syndrome demonstrate a selective deficiency of high-molecular-weight vWF, the laboratory diagnosis of vWD involves a platelet function assay (PFA) as an initial test that measures vWF antigen levels and vWF ristocetin cofactor activity. vWF multimer analysis is used as a confirmatory test if PFA is abnormal [6, 11, 19-22]. TTE or TEE is used to confirm the diagnosis of AS. GI angiodysplasia can be directly visualized using upper endoscopy or colonoscopy [2, 6, 7]. Angiodysplasias are typically seen as small, bright red, flat, or slightly raised lesions. Capsule endoscopy or enteroscopy may be required if the bleeding source is thought to be the small intestine [2, 6]. In addition, computed tomography (CT) angiography can be used in some instances to visualize angiodysplasia and to administer vasoconstrictive agents or embolization for treatment [6].

Heyde syndrome is underdiagnosed and treatable, although guidelines are lacking [23]. AVR is considered the definitive treatment for Heyde syndrome and can subvert GI bleeding. Heyde syndrome diagnosis and treatment can be delayed, and the average time to diagnosis is estimated at 2 years [6, 23]. Dahiya et al [7] reported a case of a patient with a “prolonged hospital course” due to a late diagnosis of Heyde syndrome. A high index of suspicion is warranted in patients with recurrent GI bleeding to expedite diagnosis and management [6]. While AVR appears therapeutic, not all studies found evidence of AVWS. In their review, Saha et al [6] found that only one-third of Heyde syndrome cases provided evidence of acquired coagulopathy in AVWS. Treatment modalities for isolated GAVE range from medications to endoscopic or surgical therapy in refractory cases [13]. The efficacy of AVR in treating GAVE-AS (a form of Heyde syndrome) is yet to be established, as no cases have been reported so far. Further research is needed to fully understand the pathophysiology and optimal management of this syndrome.

Learning points

In this case series, we describe Heyde syndrome in the context of AS and suggest its association with GAVE as an under-reported form of Heyde syndrome. The pathogenesis of Heyde syndrome is theorized to involve high-shear stress from AS, causing damage to vWF complexes and platelets, ultimately resulting in a bleeding diathesis. AVR has been reported to result in partial-to-complete resolution of GI bleeding, supporting this hypothesis. We propose that GAVE-AS is a variant manifestation of Heyde syndrome with unknown etiopathogenesis and management guidelines. Further research involving larger sample sizes, vWF measurements, and clear diagnostic criteria, is necessary to fully characterize this condition.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients and their families for allowing us to share these interesting cases with the rest of the medical community.

Financial Disclosure

No funding was obtained for the writing or submission of this case report.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

The patients gave their consent for the publication of this case series.

Author Contributions

LB conceptualized the idea for this case series. SO, NK, DA, and GM assisted with data curation, collection of pertinent patient information, and drafting of the manuscript. RD, KA, YC, and WB edited and proofread the final draft of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

GI: gastrointestinal; vWF: von Willebrand factor; GAVE: gastric antral vascular ectasia; NIS: National Inpatient Sample; AVWS: acquired von Willebrand syndrome; CAD: coronary artery disease; ED: emergency department; PRBCs: packed red blood cells; EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy; TTE: transthoracic echocardiogram; TEE: transesophageal echocardiogram; CABG: coronary artery bypass surgery; TAVR: transcatheter aortic valve replacement; CT: computed tomography; AVR: aortic valve replacement

| References | ▴Top |

- Heyde E. Gastrointestinal bleeding in aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1958;259:196.

- Abdelmaseih R, Thakker R, Abdelmasih R, Ali A, Hasan M. Perspectives on Heyde's syndrome and calcific aortic valve disease. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022;47(10):100930.

doi pubmed - Jamil D, Tran HH, Mansoor M, Bbutt SR, Satnarine T, Ratna P, Sarker A, et al. Multimodal treatment and diagnostic modalities in the setting of Heyde's syndrome: a systematic review. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e28080.

doi pubmed - Jehangir A, Pathak R, Ukaigwe A, Donato AA. Association of aortic valve disease with intestinal angioectasia: data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30(4):438-441.

doi pubmed - Desai R, Parekh T, Singh S, Patel U, Fong HK, Zalavadia D, Savani S, et al. Alarming increasing trends in hospitalizations and mortality with Heyde's syndrome: a nationwide inpatient perspective (2007 to 2014). Am J Cardiol. 2019;123(7):1149-1155.

doi pubmed - Saha B, Wien E, Fancher N, Kahili-Heede M, Enriquez N, Velasco-Hughes A. Heyde's syndrome: a systematic review of case reports. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2022;9(1):e000866.

doi pubmed - Dahiya DS, Kichloo A, Zain EA, Singh J, Wani F, Mehboob A. Heyde syndrome: an unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:2324709621997279.

doi pubmed - Sugimoto S, Takamura T. Disappearance of atypical gastric mucosal bleeding due to Heyde's syndrome after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2022;16(1):165-170.

doi pubmed - Aldiabat M, Aljabiri Y, Horoub A, et al. Does aortic stenosis impact the prevalence and outcomes of gastric antral vascular ectasia? A retrospective study of 85, 000 patients. 2022. p. s1136-s1137.

- Vincentelli A, Susen S, Le Tourneau T, Six I, Fabre O, Juthier F, Bauters A, et al. Acquired von Willebrand syndrome in aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(4):343-349.

doi pubmed - Flood VH. Perils, problems, and progress in laboratory diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40(1):41-48.

doi pubmed - Mondal S, Hollander KN, Ibekwe SO, Williams B, Tanaka K. Heyde Syndrome-Pathophysiology and Perioperative Implications. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35(11):3331-3339.

doi pubmed - Lageju N, Uprety P, Neupane D, Bastola S, Lama S, Panthi S, Gnawali A. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (Watermelon stomach); an unusual cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in elderly: A case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;82:104733.

doi pubmed - Morrisroe K, Hansen D, Stevens W, Sahhar J, Ngian GS, Hill C, Roddy J, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in systemic sclerosis: a study of its epidemiology, disease characteristics and impact on survival. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):103.

doi pubmed - Peng M, Guo X, Yi F, Shao X, Wang L, Wu Y, Wang C, et al. Endoscopic treatment for gastric antral vascular ectasia. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211039696.

doi pubmed - Kichloo A, Solanki D, Singh J, Dahiya DS, Lal D, Haq KF, Aljadah M, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia: trends of hospitalizations, biodemographic characteristics, and outcomes with watermelon stomach. Gastroenterology Res. 2021;14(2):104-111.

doi pubmed - Fortuna L, Bottari A, Bisogni D, Coratti F, Giudici F, Orlandini B, Dragoni G, et al. Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (GAVE) a case report, review of the literature and update of techniques. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;98:107474.

doi pubmed - Dosi RV, Ambaliya AP, Patell RD, Sonune NN. Gastric antral vascular ectasia with aortic stenosis: Heydes syndrome. Indian J Med Sci. 2012;66(3-4):86-89.

pubmed - Rosa VEE, Ribeiro HB, Fernandes JRC, Santis A, Spina GS, Paixao MR, Pires LJT, et al. Heyde's syndrome: therapeutic strategies and long-term follow-up. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021;117(3):512-517.

doi pubmed - Sinha S, Castro D, Shakil S. Medical management of Heyde syndrome. Cureus. 2021;13(1):e12551.

doi pubmed - Waldschmidt L, Drolz A, Heimburg P, Gossling A, Ludwig S, Voigtlander L, Linder M, et al. Heyde syndrome: prevalence and outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021;110(12):1939-1946.

doi pubmed - Blackshear JL. Heyde syndrome: aortic stenosis and beyond. Clin Geriatr Med. 2019;35(3):369-379.

doi pubmed - Lourdusamy D, Mupparaju VK, Sharif NF, Ibebuogu UN. Aortic stenosis and Heyde's syndrome: A comprehensive review. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(25):7319-7329.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.