| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 1, January 2025, pages 11-16

Ciprofloxacin-Induced Encephalopathy

Adelle Kanana, Alexander T. Phanb, c , Haroon Azhandb, Katherine E. Bourbeau-Medinillab

aCalifornia University of Science and Medicine, Colton, CA 92324 USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, Colton, CA 92324, USA

cCorresponding Author: Alexander Phan, Department of Internal Medicine, Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, Colton, CA 92324, USA

Manuscript submitted June 3, 2024, accepted July 16, 2024, published online December 21, 2024

Short title: Ciprofloxacin Encephalopathy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc4264

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Fluoroquinolones (FLQs) are commonly prescribed for infections in both the inpatient and outpatient setting. Though typically well-tolerated, FLQs have been associated with central nervous system adverse effects, especially in older adults and those who metabolize medications at suboptimal rates. Rarely, these drugs can cause serious neurotoxic manifestations, such as seizures, psychosis, or encephalopathy. Although new quinolone derivatives like levofloxacin are most associated with neurotoxic side effects, we show that these unwanted side effects can occur with ciprofloxacin as well. Clinicians should be aware of the neurotoxic side effects of FLQs and its predisposing risk factors, as this is a commonly prescribed class of medication. We aim to contribute to the limited body of literature describing neurotoxic clinical manifestations of FLQs. Herein, we present a case of an 88-year-old male with underlying dementia who presented to the emergency department for evaluation of acute encephalopathy.

Keywords: Encephalopathy; Fluoroquinolones; Ciprofloxacin; Medication adverse effects

| Introduction | ▴Top |

There are many etiologies for an encephalopathic state, and medications often warrant consideration as a cause. Common medications leading to delirium include antimicrobials, antihistamines, antihypertensives, anticholinergics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, diuretics, opioids, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications [1]. Out of the antimicrobials, fluoroquinolones (FLQs) in particular are associated with rare but serious neurotoxic manifestations, including seizures, confusion/encephalopathy, myoclonus, oro-facial dyskinesias, extrapyramidal manifestations, and toxic psychosis [2]. Although not thoroughly elucidated, potential mechanisms for FLQ-mediated neurotoxicity involve inhibition of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA-A) receptors and activation of excitatory N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors [3, 4].

The risk of FLQ-associated adverse central nervous system (CNS) effects depends on a few physiological factors. Of note, the patient’s nutritional status, blood flow, blood-brain barrier integrity, genetic factors, renal insufficiency, and the drug’s CNS penetration may contribute to neurotoxicity [2]. Many protective factors also tend to decline with age, while injurious aspects increase. For instance, renal function worsens consistently with age, affecting excretion of FLQs and potentially making older adults more prone to CNS reactions [5]. Here, we report the case of an 88-year-old patient who became encephalopathic following treatment with ciprofloxacin for a urinary tract infection (UTI).

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

The patient is an 88-year-old male with a history of dementia (requiring assistance with activities of daily living), hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and hearing loss with use of hearing aids at home who presented to the hospital due to acute encephalopathy. The patient’s baseline mentation was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. He was also normally able to ambulate independently. Per the patient’s wife, prior to hospital presentation, he had been diagnosed with a UTI and was started on a 3-day course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily 5 days prior to hospital presentation. Shortly after, the patient started to become confused, incoherent, and difficult to arouse.

Upon arrival at the emergency department, vital signs were blood pressure 166/72 mm Hg, pulse rate of 77, respiratory rate of 18, temperature of 36.6 °C, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. Physical exam revealed disorientation, with the patient only alert and oriented to self. He was noted by staff to be non-redirectable. The patient was uncooperative with the neurologic examination, but appeared to have full range of motion of all extremities. Physical exam showed a normocephalic, atraumatic head, reactive pupils, regular heart rate and rhythm without murmurs, normal breath sounds bilaterally, and a flat, soft, and non-tender abdomen. Social history was negative for illicit substance or alcohol use. Home medications included lisinopril, atorvastatin, and low-dose aspirin.

Diagnosis

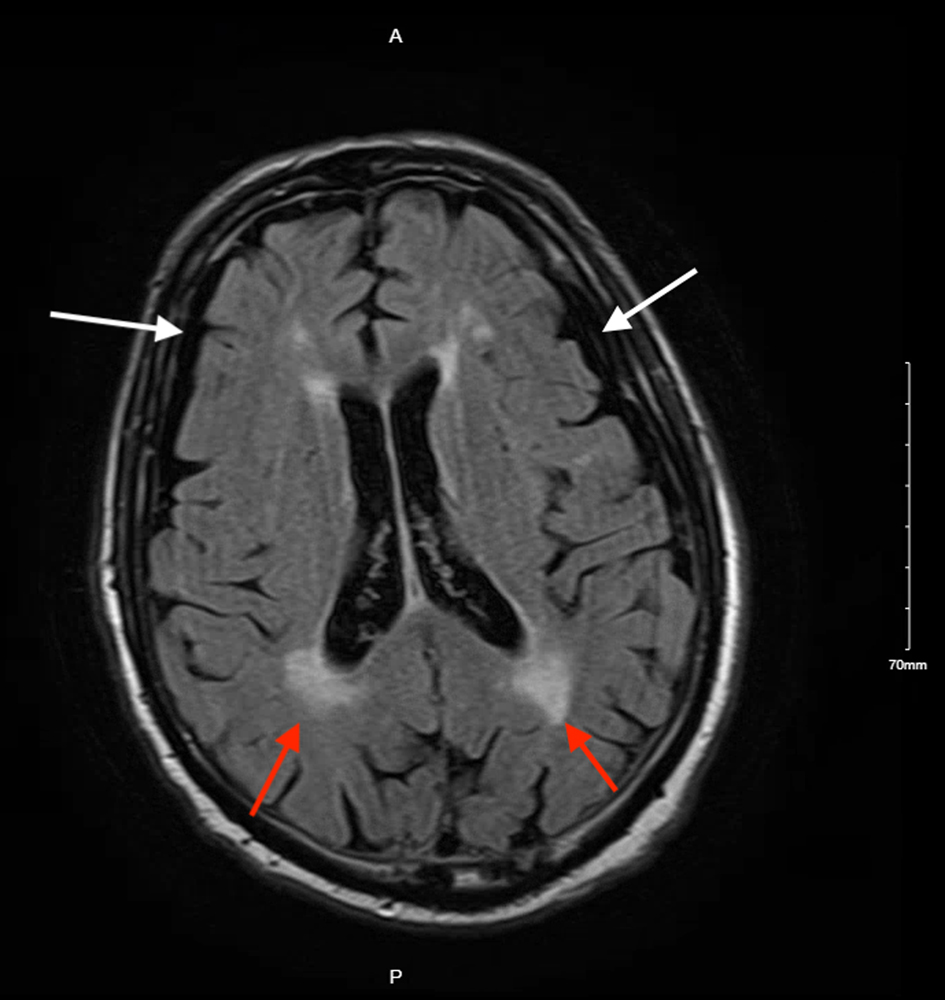

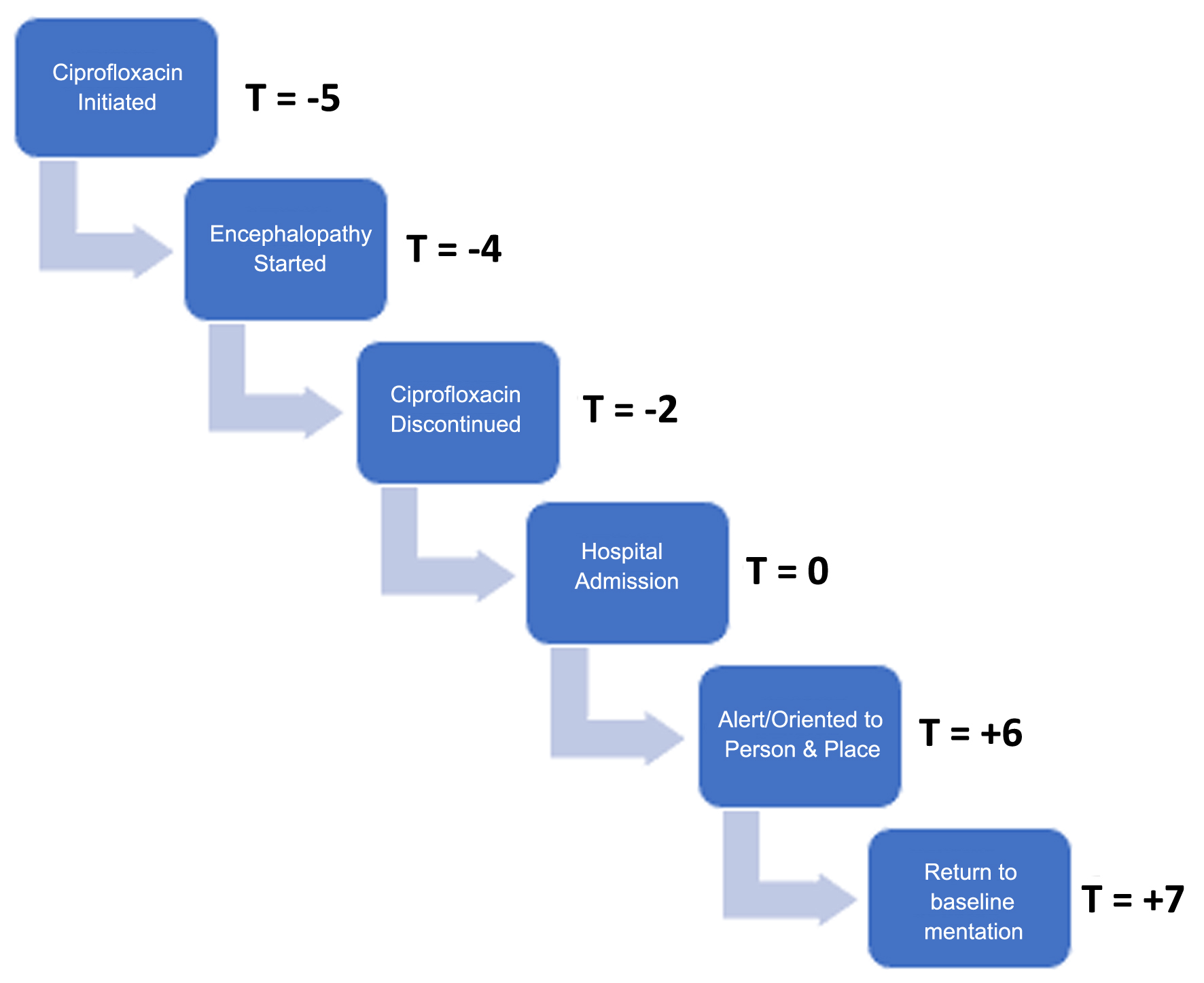

Initial laboratory evaluation demonstrated no immediate explanation for the patient’s altered mental status. The complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel (BMP), serum vitamin B12, serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), respiratory viral panel, acute hepatitis panel, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screening, and syphilis screening were all within reference range (Table 1). Serum ammonia was 1 µg/dL below the reference range and was not considered to be clinically significant. An initial urinalysis was not obtained due to the patient’s refusal to urinate. He was started on empiric intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone (details listed in the “Treatment” section). Of note, urinalysis from hospital day 2 showed 1+ blood, 1+ protein, and trace ketones, but no suggestion of a UTI, though the patient had already received antibiotics at this time (Table 2). The trace ketones were likely a manifestation of poor oral intake secondary to the patient’s encephalopathy. An electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia with premature atrial contractions. A chest radiograph did not show evidence of pneumonia or acute disease. Computed tomography (CT) of the head was complicated by motion artifact, but revealed no gross intracranial hemorrhage. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head exhibited mild atrophy and chronic white matter changes, but no acute pathologies were identified (Fig. 1). Six days after the patient presented to the hospital, the patient had been off of ciprofloxacin for 8 days. At this point in time, his mentation had improved to being alert and oriented to person and place. On hospital day 7, his mentation returned to baseline. Based on the negative diagnostic work-up and temporal association with the initiation and discontinuation of ciprofloxacin, a diagnosis of ciprofloxacin-induced encephalopathy was reached. A summary of the patient’s clinical course is provided in Figure 2.

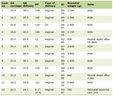

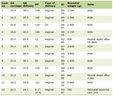

Click to view | Table 1. Initial Laboratory Findings Showing a Normal Complete Blood Count, Basic Metabolic Panel, Syphilis Screen, Human Immunodeficiency Virus Screen, Vitamin B12 Level, and Hepatitis Panel |

Click to view | Table 2. Urinalysis on Hospital Day 2 Without Evidence of Infection |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Axial section of a brain magnetic resonance imaging showing mild cortical atrophy (white arrows) and chronic white matter changes (red arrows), without acute pathology. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Graphical representation of the patient’s clinical course demonstrating onset of symptoms and time to recovery. Time is displayed with 0 indicating date of hospital admission and cessation of ciprofloxacin (T = 0). Each day prior is notated by a negative sign and each day after is notated by a positive sign (e.g. T = -5 indicates five days prior to hospital admission). |

Treatment

The patient received 5 days of IV ceftriaxone 2 g once daily for treatment of a UTI and ciprofloxacin was never initiated in the hospital. Treatment with antibiotics was started because infectious etiology could not be completely ruled out. The patient tolerated the medication well.

Follow-up and outcomes

On hospital day 7, the patient was back to his baseline mentation and was stable for discharge back to his home with his wife. On follow-up 1 month post-discharge, the patient is doing well at home with his wife.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case centers on the clinical progression of a male patient with underlying dementia and a recent UTI treated with ciprofloxacin who presented with altered mental status. The initial differential diagnosis for our patient included altered mental status secondary to adverse medication effects, infectious etiologies, metabolic encephalopathy, worsening dementia, and cerebral infarct or hemorrhage. Our investigation ruled out UTI with an initial urinalysis devoid of leukocytes, nitrite, or bacteria and a urinary culture that grew nothing at 24 h. Nasopharyngeal swab testing was negative for coronavirus, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus. Sexually transmitted infection tests were negative, as was the acute hepatitis panel, making an infectious cause less likely. The patient’s laboratory values from a CBC and BMP showed no signs of thyroid issues, liver dysfunction, or kidney insufficiency that would point toward metabolic encephalopathy. The relatively sudden decrease in the patient’s mental function made worsening dementia unlikely as the primary cause, although the patient’s dementia may have made him more prone to experiencing delirium. Finally, CT and MRI showed no signs of acute nor subacute cerebral pathology, though previous punctate parenchymal hemorrhages probably made the patient more susceptible to changes in mentation. Due to inability to explain the patient’s encephalopathic state from common causes, along with his temporally associated course of ciprofloxacin, FLQ-induced encephalopathy became our leading diagnosis.

The CNS excitatory effects of FLQs make these antibiotics more risky for older individuals. Stahlmann and Lode rightfully point out that adverse reactions to FLQs, such as confusion, weakness, loss of appetite, tremor, or depression, are frequently misattributed to the effects of aging [5]. They also remind us that because of physiological changes and certain comorbidities more prevalent in older populations, caution needs to be taken when older adults are treated with these FLQs [5].

Dementia in particular is a comorbidity of concern when considering older patients’ risk for CNS side effects. The prevalence of delirium superimposed on dementia (DSD) ranges from 22% to 89% in individuals 65 and older [6]. This is clinically significant because individuals with DSD experience a hastened decline in cognitive and functional capabilities, elevated risk of rehospitalization, and higher mortality rates [6]. Therefore, any medical treatments that can precipitate delirium must be used with caution. Importantly, our patient was later in his lifespan and had already been diagnosed with dementia, making him more susceptible to severe adverse reactions from FLQs.

FLQ-associated CNS adverse reactions are relatively rare but well documented, occurring in approximately 1-2% patients [7, 8]. Therefore, FLQ encephalopathy tends to be a diagnosis of exclusion, necessitating that providers rule out more common causes such as anticholinergic medication use, infection, metabolic etiologies, neurologic/psychiatric conditions, and systemic organ failure. Many of the documented cases of FLQ-induced altered mental status implicate levofloxacin specifically, most likely because of the newer quinolone derivative’s specific affinity for the GABA and NMDA receptors [9]. Hakko et al reported the case of a 73-year-old male patient with levofloxacin-treated pneumonia who became disoriented, confused, and hyperactive 2 days after medication administration, with complete symptom resolution 48 h after discontinuing levofloxacin treatment [10]. Reddy et al described a 51-year-old man who presented with a 3-month history of disturbed consciousness, confusion, disorientation, ataxic gait, and jerking body movements after being administered levofloxacin along with other medications for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, with full recovery after the FLQ was withheld [11]. In our patient’s case, he presented 2 days after stopping ciprofloxacin. The pharmacokinetics in older adults show that the elimination half-life of the medication is 4.3 h in patients like the one in our case [12]. Though the medication may have been eliminated from the patient’s body by the time of hospital presentation, his co-morbidities and acute illness may have prolonged his mental status recovery.

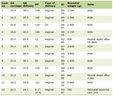

Ciprofloxacin is less well known to cause an encephalopathic state, due to the dearth of patient cases in the available literature, but it is still recognized as a potential trigger. Al Bu Ali reported a case of an adolescent male treated for pneumonia with ciprofloxacin who developed dizziness, drowsiness, dyspnea, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and MRI findings pathognomonic for posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), with resolution after discontinuation of ciprofloxacin [13]. A summary of all the cases referenced in this article are in Table 3 [8-10, 12]. Because there are few documented cases of ciprofloxacin-induced encephalopathy, our case is of particular interest. Our case study’s greatest strength was our in-depth exploration of the most likely avenues that could lead to encephalopathy. One extra study we could have considered ordering was an electroencephalogram (EEG) to assess for seizure activity or diffuse slowing, as there have been reports of abnormal EEGs in patients taking FLQs [2, 11]. Additionally, it cannot be completely ruled out that there may have been an unidentified environmental exposure that could have explained the patient’s symptoms. Despite these limitations, we think our case adds something of value to the sparse literature concerning ciprofloxacin-induced encephalopathy. Finally, though not specifically pertinent to this patient’s case, since we discuss the side effects of FLQs, it is also important to mention that FLQs also are labeled with a black box warning by the United States Food and Drug Administration [14].

Click to view | Table 3. Summary of Cases of Fluoroquinolone-Related Encephalopathy |

FLQs are a known, although relatively rare, precipitant of altered mental status, especially in individuals who have dementia, renal impairment, or are over the age of 65. We describe a case of an elderly patient with underlying dementia who developed encephalopathy after his UTI was treated with ciprofloxacin. After discontinuation of ciprofloxacin, the patient returned to his baseline mentation. Although new quinolone derivatives like levofloxacin are most associated with CNS side effects, we show that these negative reactions might occur with ciprofloxacin as well. Clinicians should consider medication-induced encephalopathy in the differential diagnosis of acute encephalopathy.

Learning points

Our case report aims to contribute to the limited current body of literature citing ciprofloxacin-induced encephalopathy. Physicians should always consider medications as a possible etiology for encephalopathy. Though typically well-tolerated, ciprofloxacin can be associated with acute encephalopathy. Physicians should perform a full medication reconciliation as a best practice and reduce polypharmacy whenever possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank and express their gratitude to Arrowhead Regional Medical Center’s exceptional nursing staff and unit managers for their expert clinical support.

Financial Disclosure

The authors have no financial or funding disclosures.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the family of the patient. The patient was also appropriately de-identified for this manuscript.

Author Contributions

AK, ATP, and HA contributed to the initial manuscript write-up, literature review, and editing of the manuscript. KEB supervised the case and contributed to the literature review and editing of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

BMP: basic metabolic panel; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; CBC: complete blood count; CNS: central nervous system; CT: computed tomography; dL: deciliter; DSD: delirium superimposed on dementia; EEG: electroencephalogram; FLQs: fluoroquinolones; g: gram; GABA: gamma-aminobutyric acid; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IV: intravenous; L: liter; mEq: milliequivalent; mg: milligram; mL: milliliter; mIU: milli-international units; µL: microliter; mm Hg: millimeters of mercury; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; PRES: posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome; TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone; UTI: urinary tract infection

| References | ▴Top |

- Chyou TY, Nishtala PS. Identifying frequent drug combinations associated with delirium in older adults: Application of association rules method to a case-time-control design. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30(10):1402-1410.

doi pubmed - Grill MF, Maganti RK. Neurotoxic effects associated with antibiotic use: management considerations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(3):381-393.

doi pubmed - Akahane K, Tsutomi Y, Kimura Y, Kitano Y. Levofloxacin, an optical isomer of ofloxacin, has attenuated epileptogenic activity in mice and inhibitory potency in GABA receptor binding. Chemotherapy. 1994;40(6):412-417.

doi pubmed - Akahane K, Sekiguchi M, Une T, Osada Y. Structure-epileptogenicity relationship of quinolones with special reference to their interaction with gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor sites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33(10):1704-1708.

doi pubmed - Stahlmann R, Lode H. Safety considerations of fluoroquinolones in the elderly: an update. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(3):193-209.

doi pubmed - Flanagan NM, Fick DM. Delirium superimposed on dementia. Assessment and intervention. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(11):19-23.

doi pubmed - Zareifopoulos N, Panayiotakopoulos G. Neuropsychiatric effects of antimicrobial agents. Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(5):423-437.

doi pubmed - Lipsky BA, Baker CA. Fluoroquinolone toxicity profiles: a review focusing on newer agents. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28(2):352-364.

doi pubmed - Kiangkitiwan B, Doppalapudi A, Fonder M, Solberg K, Bohner B. Levofloxacin-induced delirium with psychotic features. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(4):381-383.

doi pubmed - Hakko E, Mete B, Ozaras R, Tabak F, Ozturk R, Mert A. Levofloxacin-induced delirium. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107(2):158-159.

doi pubmed - Reddy V, Mittal GK, Sekhar S, Singhdev J, Mishra R. Levofloxacin-Induced Myoclonus and Encephalopathy. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2020;23(3):405-407.

doi pubmed - Bayer A, Gajewska A, Stephens M, Stark JM, Pathy J. Pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in the elderly. Respiration. 1987;51(4):292-295.

doi pubmed - Ali WH. Ciprofloxacin-associated posterior reversible encephalopathy. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013008636.

doi pubmed - Tanne JH. FDA adds "black box" warning label to fluoroquinolone antibiotics. BMJ. 2008;337(7662):a816.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.