| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 2, February 2025, pages 55-60

“False” False Tendon: Fatal Intramyocardial Dissecting Hematoma

Kahtan Fadaha, d, Seyed Khalafib, Ezhil Panneerselvama, Jan Lopesc, Mehran Abolbasharic, Jorge Chiquie Borgesc, Kazue Okajimac

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso, TX, USA

bPaul L. Foster School of Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso, TX, USA

cDivision of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso, TX, USA

dCorresponding Author: Kahtan Fadah, Department of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso, TX 79905, USA

Manuscript submitted December 12, 2024, accepted December 27, 2024, published online January 17, 2025

Short title: Fatal IDH

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5096

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Intramyocardial dissecting hematoma (IDH) is a rare complication that may emerge from myocardial infarction, thoracic injury, or percutaneous intervention. In the past, IDH was diagnosed through surgical intervention or postmortem autopsy. We present a case of a 70-year-old male with comorbidities who admitted to the intensive care unit after suffering out of hospital pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest and obtained return of spontaneous circulation after chest compressions. Initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ST elevation in the anterolateral leads. Repeated ECG a few minutes later showed junctional rhythm bradycardia with a rate of 27 and serial changes of an anterolateral infarct were present and placed on percutaneous pacing with vasopressors. The troponin I peaked at 1.880. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) portrayed a hyperechoic mobile filamentous structure near the cardiac apex, which was thought to be a false left ventricular (LV) tendon initially. A repeat TTE with the use of an ultrasound enhancing agent (sulfur hexafluoride) revealed an apical neocavity with no contrast filling, suggestive of a large apical IDH within the LV. The patient expired because of cardiac arrest secondary to cardiogenic shock refractory to pressor support, with no autopsy performed. This case highlights an uncommon and timelier diagnostic modality of IDH in deference of more costly and prolonged imaging studies.

Keywords: Intramyocardial dissecting hematoma; Myocardial infarction; Cardiac imaging

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Intramyocardial dissecting hematoma (IDH) is a very uncommon complication that can emerge due to a myocardial infarction (MI), thoracic injury, or percutaneous intervention [1]. It is described as a hemorrhagic dissection between layers of spiral myocardial fibers from either the rupture of intramyocardial vessels, decreased tensile strength of the infarcted muscle tissue, or acute increase in coronary capillary perfusion pressure [2]. The cause is speculated to be due to swelling of endothelial cells causing gaps in the endothelial lining, with reperfusion leading to extravasation of red blood cells [3]. IDH can develop in the left ventricular (LV) free wall, the right ventricle, or the interventricular septum [1] and may evolve into a ventricular rupture or reabsorb spontaneously [4]. Prior to the imaging era, IDH was diagnosed through surgical intervention or postmortem during autopsy [5]. In this article, we report a unique case of an LV IDH in a patient with an old MI after prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) diagnosed using contract-enhanced echocardiography.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 70-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension, heart failure diagnosed in 2018 with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 30-35%, MI with a left anterior descending stent in 2010, a non-ST elevation MI in 2015, chronic kidney disease, and rheumatoid arthritis was admitted to the intensive care unit after suffering out of hospital pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest. The patient was at home that night when he experienced an episode of nausea with non-bloody emesis. He was found unresponsive and pulseless in the bathroom floor by his wife, who is a nurse, and chest compressions were begun. There had been no earlier reports of chest pain or any other complaints. The patient was functionally active and capable of performing his daily activities independently. Upon arrival to the emergency department, resuscitation efforts were continued and return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was obtained after nearly 20 min of total downtime. On physical exam, the patient was comatose intubated and ventilated with a heart rate of 20 - 30 beats per minute of sinus rhythm, with blood pressure of 105/73. On auscultation, there were no murmurs or gallops, diffuse crackles noted in bilateral lungs, and upper and lower extremities were noted to be cool to touch. Laboratory findings revealed acutely low hemoglobin (10.9 g/dL), low hematocrit (35.9%), low platelet count (56 × 103/µL), high prothrombin (international normalized ratio time 2.1), high blood urea nitrogen (70 mg/dL), high N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (> 35,000 pg/mL), high lactic acid (13.9 mmol/L), high potassium (6.9 mmol/L), and severe acidosis with a low bicarbonate (12.5 mmol/L) and a pH of 6.974. The patient was also noted to have a chronically elevated creatinine (4.3 mg/dL). The troponin I peaked at 1.880, suggestive of no acute coronary events.

Diagnosis

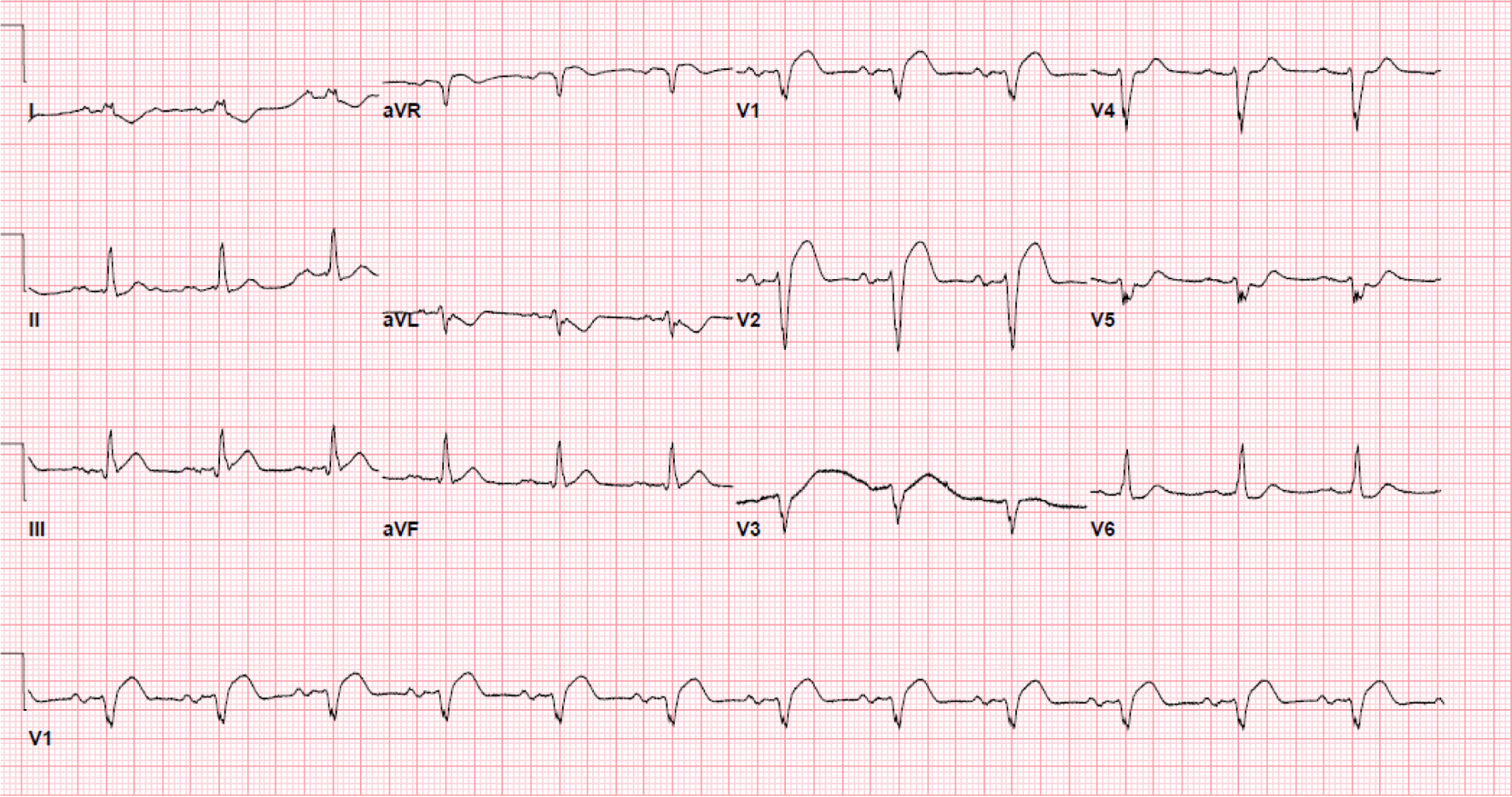

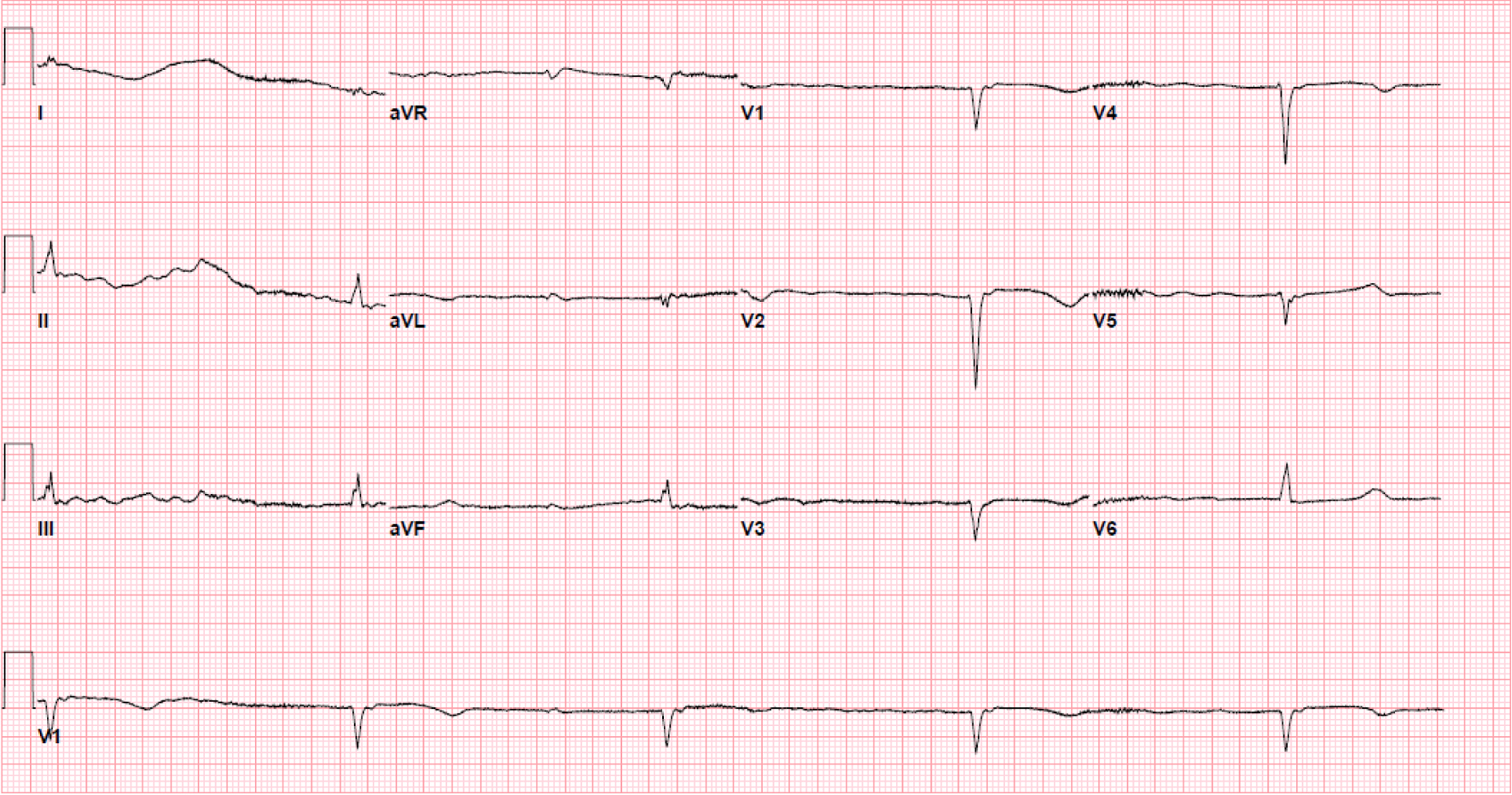

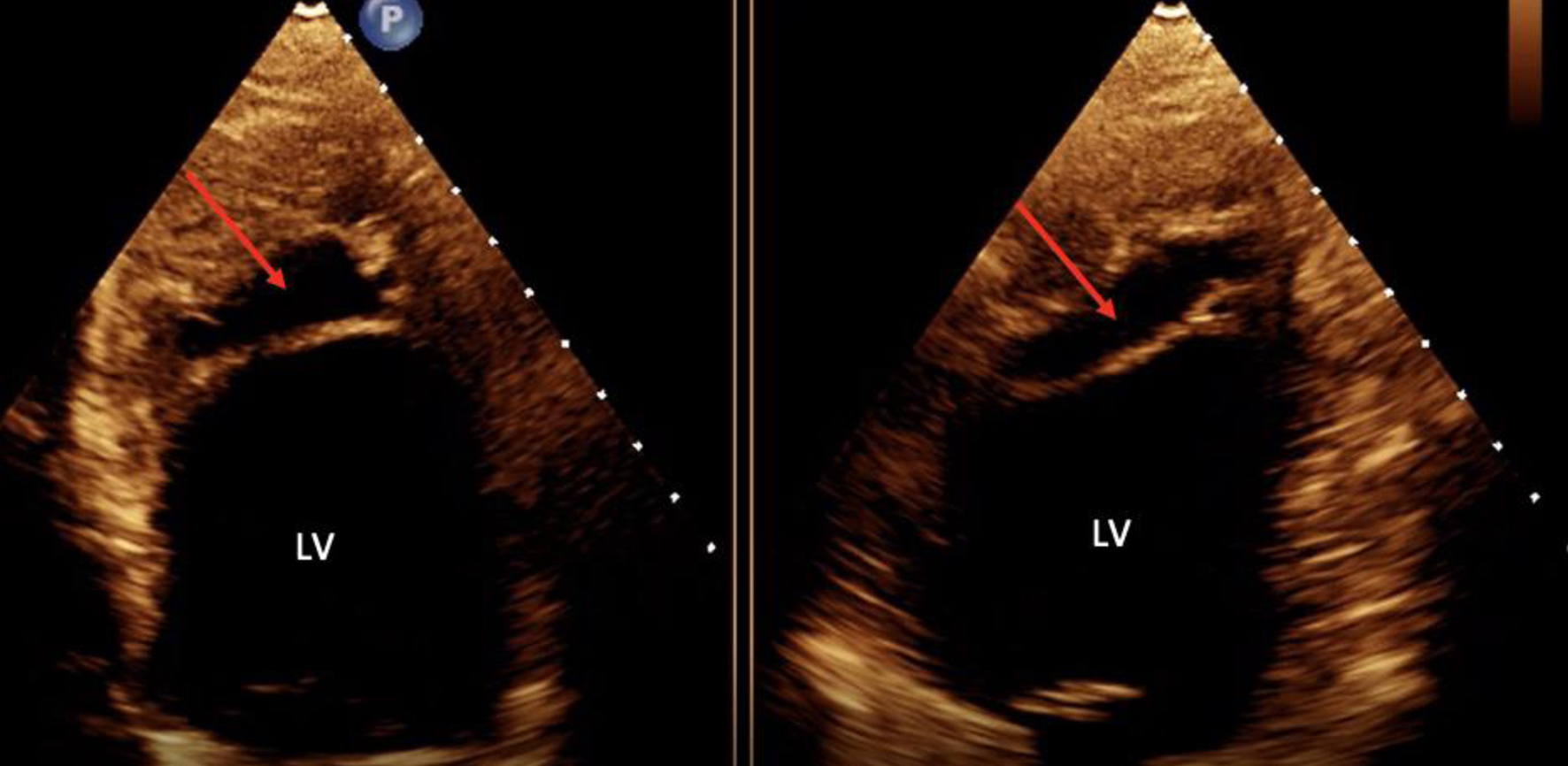

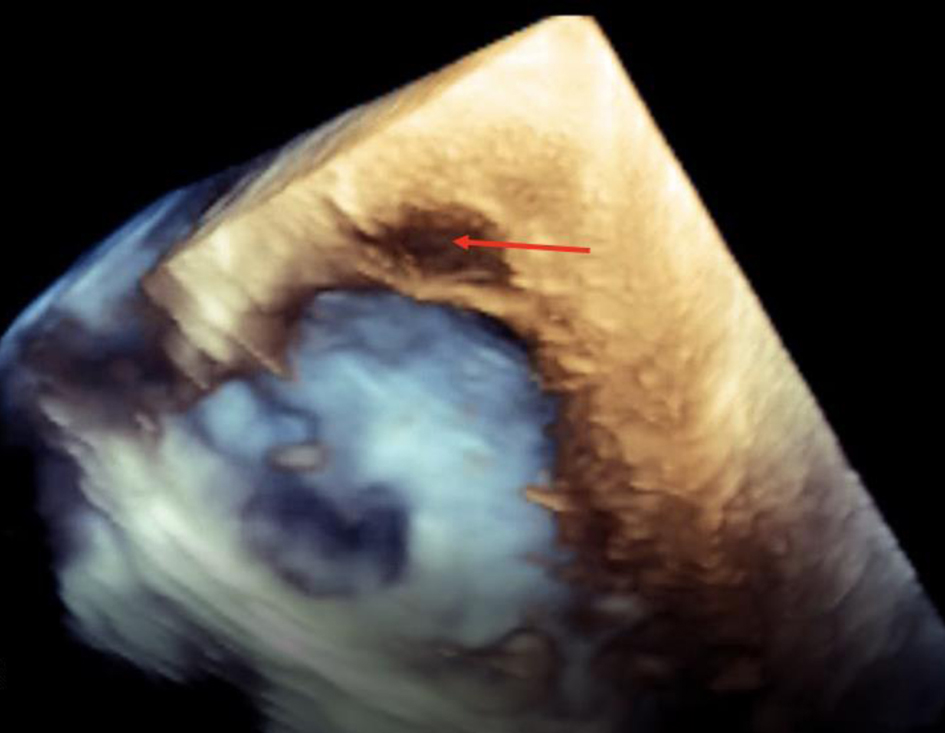

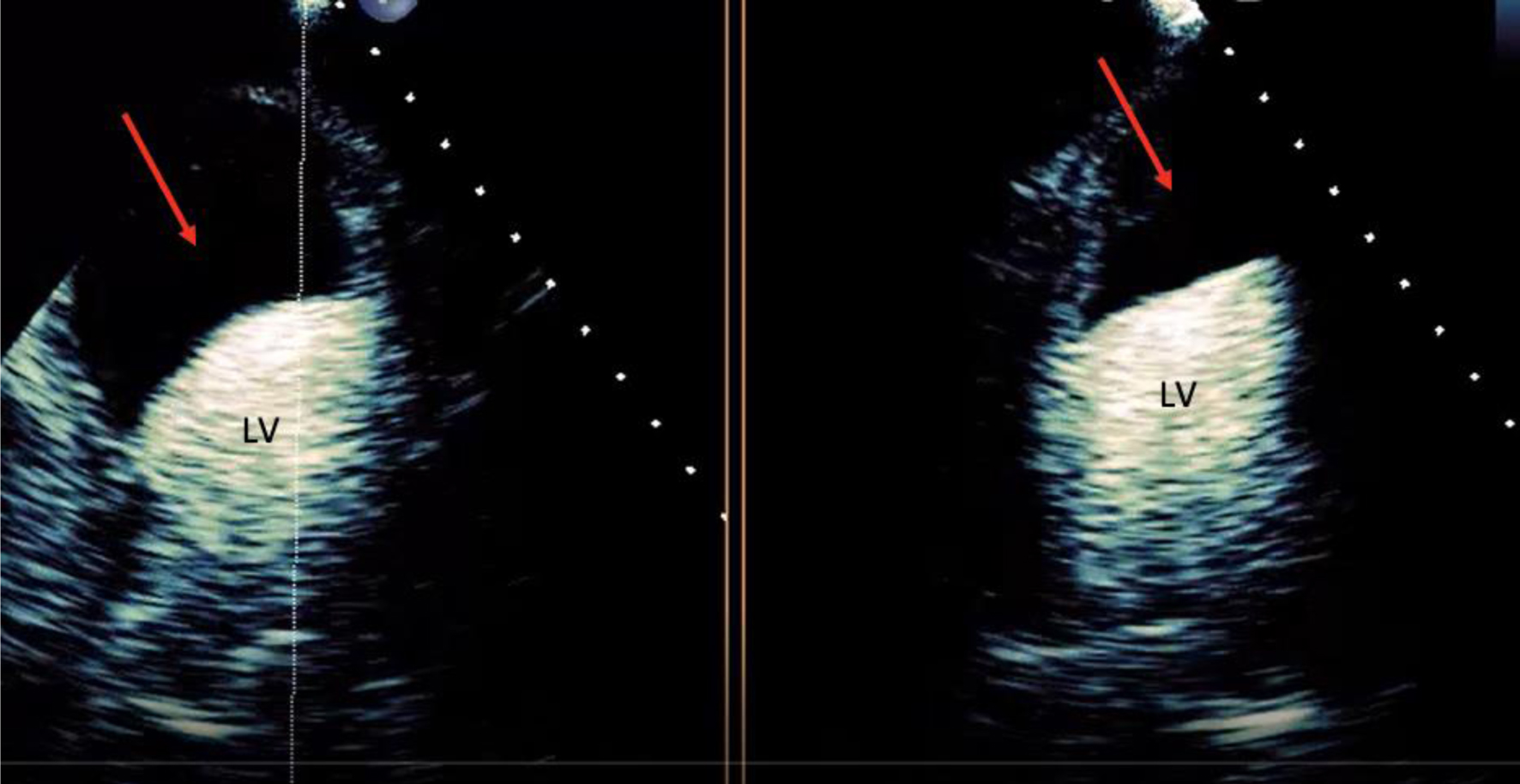

Initial electrocardiogram (ECG) right after obtaining ROSC showed ST elevation in the anterolateral leads (Fig. 1). Repeated ECG a few minutes later showed junctional rhythm bradycardia with a rate of 27 and serial changes of an anterolateral infarct were present (Fig. 2). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) demonstrated reduced LVEF of 20-25% with global hypokinesis and apical akinesis with hyperechoic mobile filamentous structure near the cardiac apex, which was thought to be a false LV tendon initially (Figs. 3 and 4). A repeat TTE with the use of an ultrasound enhancing agent (sulfur hexafluoride) revealed an apical neocavity with no contrast filling, suggestive of a large apical IDH within the LV (Figs. 5 and 6).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Initial electrocardiogram showing ST elevation in the anterolateral leads. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Electrocardiogram a few minutes after the initial showing junctional rhythm bradycardia with a rate of 27 and serial changes typical for progression of anterolateral infarct. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Transthoracic echocardiogram in the four-chamber and two-chamber view without contrast showing hyperechoic mobile filamentous structure (red arrows) near the cardiac apex in the left ventricle. LV: left ventricle. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Transthoracic echocardiogram in three-dimensional view without contrast showing hyperechoic mobile filamentous structure suggestive of IDH (red arrow) near the cardiac apex. |

Click for large image | Figure 5. Transthoracic echocardiogram in the four-chamber and two-chamber view with contrast suggestive of intramyocardial dissecting hematoma (red arrow). LV: left ventricle. |

Click for large image | Figure 6. Transthoracic echocardiogram in the parasternal short axis with contrast in the left ventricle suggestive of intramyocardial dissecting hematoma (red arrow). LV: left ventricle. |

Treatment

Hospital course was complicated by acute kidney failure requiring renal replacement therapy, refractory shock and multiorgan dysfunction. Following these findings, the patient was placed on percutaneous pacing with vasopressors including norepinephrine and epinephrine. Their potassium was corrected, and bicarbonate stores were replenished. Due to these conditions, coronary angiogram, computed tomography (CT) with contrast or cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging could not be performed to evaluate IDH.

Outcomes

The patient expired on hospital day 6 because of cardiac arrest secondary to cardiogenic shock refractory to pressor support. An autopsy was not performed.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

IDH is a rare complication and occurs in approximately 0.45% of patients with an ST elevation MI [3]. Our patient’s IDH was most likely caused by CPR-induced thoracic injury, as there were no signs of acute MI during initial presentation. IDH has been increasingly recognized due to continuous improvement of cardiac imaging techniques. For diagnosing IDH, TTE is a useful modality for initial assessment of IDH at bedside and contrast TTE enhances a rapid diagnosis. Bedside TTE is usually the most common setting, IDH is first suggested as a differential diagnosis, with others being pseudoaneurysm, intracavitary thrombus, or prominent ventricular trabeculations [6]. One specific feature of IDH is a characteristic sustained ST segment elevation [7]. CMR and CT carry a more accurate diagnosis, although there may be limitations in hemodynamically unstable patients. CMR is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of IDH; however, it comes with limitations due to its cost and delay in diagnosis. In our patient with hemodynamic instability with multiorgan dysfunction, a TTE was the most practical and appropriate diagnostic tool.

TTE/transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was the most commonly used diagnostic modality for IDH. The prioritization of TTE is due to its ability to show the varying patterns of IDH, in addition to the varying stages of resorption and the formation of a thrombus. Commonly, IDH can be misinterpreted as an LV thrombus or cardiac rupture surrounded by the pericardium (ventricular pseudoaneurysm) [7]. The characteristics that suggest an IDH on TTE include multiple echo-lucent regions, a thin layer of mobile endocardium or myocardium on one side and a thicker layer of myocardium with pericardium on another side. The color flow Doppler may also show flow into the cavity [8-10]. The lucency of the cavity in an IDH can also vary depending on the timing of TTE, as the collection of blood in the cavity may be free flowing or formed a thrombus [9]. Similarly, our patient’s TTE shows many of the above characteristics that could suggest IDH. The use of TTE however does come with limitations, as flow velocities in larger defects will be low. Additionally, the angling nature of the color Doppler may also underestimate its accuracy, hence why other imaging modalities of echocardiography should be used, including contrast echo and/or TEE [5]. Other modalities include CT or CMR if available, as these may help differentiate IDH between other conditions that may mimic, such as LV cavitary thrombus and LV aneurysm [8, 11]. Surgical diagnosis and cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA) were performed as well. A case report by Tanabe et al showed a similar presentation of IDH after MI that was diagnosed by TTE and CMR [9]. In contrast to our study, we were able to forgo CMR testing and use contrast TTE to more rapidly and cost effectively diagnose IDH.

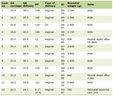

The majority of IDH cases are reported with an MI, with most patients dying shortly after diagnosis. Most commonly, dissecting hematomas occur in the LV following an MI, followed by the left atrium after ablation procedures [8]. Trauma has also been seen in previous case reports as a cause of IDH. A literature review of IDH resulted in four cases of trauma-associated IDH cases reported up until 2024 (Table 1). All of these cases were the result of motor vehicle accident (MVA) trauma [12-15]. Our patient did not present with signs of MI as his troponin was not significantly elevated. With his history of prolonged CPR, this may suggest trauma as a cause of his IDH, which is unique compared to all other reported cases of chest trauma [14, 16].

Click to view | Table 1. Literature Review on Diagnosis of Intramyocardial Dissecting Hematoma due to Trauma |

The mortality rate of IDH can be as high as 90% without surgical intervention [7]. The risk of mortality and management depends on low ejection fraction, age > 60, and late diagnosis, with the greatest predictor being low ejection fraction [11, 17]. As for our case, the patient had an ejection fraction of 20-25% and was 70 years old, suggesting a poor prognosis. The poor prognosis is due to the dissecting hematoma advancing to a cardiac rupture, leading to LV failure and/or cardiac tamponade [5]. No treatment plan has been established for IDH. However, Alyousef et al suggested that hemodynamically stable patients with a small IDH limited to the apex without high-risk features can be managed conservatively, compared to patients with evidence of expansion and hemodynamic instability requiring surgical intervention [7]. In the study conducted by Vargas-Barron et al, the authors suggested that if the hematoma is contained within the apical segments of the ventricular walls, there is a high probability of spontaneous reabsorption, and conservative management can be taken. However, if the hematoma extends into the septum or right ventricle from the apical segments through serpiginous tracts, a surgical approach should be taken [10]. Zhao et al showed that low LVEF, late diagnosis (> 24 h after the onset of symptoms), pericardial effusion, and ages over 60 years associated with a worse outcome. There was however no difference in mortality rate between location of the IDH and between surgically and medically treated patients [1, 5, 18]. Cardiac transplantation has also been considered for patients who are not surgical candidates [8]. With many uncertainties involving this condition, the more documentations involving IDH may help establish diagnostic and treatment plans.

Conclusion

We observed an unusual case of IDH in a patient with old MI after prolonged CPR. Other conditions may mimic an IDH, and proper and early diagnosis are important to guide therapy. The contrast TTE was useful for a rapid diagnosis at bedside for this critically ill patient.

Learning points

IDH is a rare complication of MI, thoracic injury, or percutaneous intervention. There are however minimal case reports of IDH caused by thoracic injury. CMR and CT are more accurate in diagnosing IDH but are limited in unstable patients and prolong diagnosis. TTE/TEE has been commonly used to help in the diagnosis of IDH, with contrast echo sparingly used. The use of TTE with contrast echo helps with early diagnosis of IDH and is more cost effective. The sooner IDH is diagnosed, the sooner complications from the condition may be prevented. The mortality rate of IDH can be as high as 90% without surgical intervention, with risk factors for poor prognosis including low ejection fraction, age > 60, and late diagnosis, with the greatest predictor being low ejection fraction. There is currently no diagnostic or treatment plan for IDH, and the more cases reported may help in implementation of one.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

KF and SK designed this report, participated in collecting and interpreting data, collected literature review, and prepared all figures. KF, SK, EP, and JL participated in self-drafting the manuscript. MA, JCB, and KO participated in critical revising of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Agarwal G, Kumar V, Jr., Srinivas KH, Manjunath CN, Prabhavathi B. Left ventricular intramyocardial dissecting hematomas. JACC Case Rep. 2021;3(1):94-98.

doi pubmed pmc - Roslan A, Jauhari Aktifanus AT, Hakim N, Megat Samsudin WN, Khairuddin A. Intramyocardial dissecting hematoma in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: role of multimodality imaging in three patients treated conservatively. CASE (Phila). 2017;1(4):159-162.

doi pubmed pmc - Kadziola O, Molek P, Zalewski J, Urbanczyk-Zawadzka M, Nessler J, Gackowski A. Apical intramyocardial dissecting hematoma: a rare complication of acute myocardial infarction. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2021;131(10):16055.

doi pubmed - Rezaei-Kalantari K, Saedi S, Alizadeasl A, Naghshbandi M. Left ventricular intra-myocardial dissection after myocardial infarction. Echocardiography. 2020;37(12):2160-2162.

doi pubmed - Zhao Y, He YH, Liu WX, Sun L, Han JC, Man TT, Gu XY, et al. Intramyocardial dissecting hematoma after acute myocardial infarction-echocardiographic features and clinical outcome. Echocardiography. 2016;33(7):962-969.

doi pubmed - Sarkar S, Majumder B, Ghosh R, Chakraborty S. A rare case of intramyocardial dissecting hematoma following acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2023;33(2):92-94.

doi pubmed pmc - Alyousef T, Malhotra S, Iskander F, Gomez J, Basu A, Tottleben J, Doukky R. Left ventricular intramyocardial dissecting hematoma: a multimodality imaging diagnostic approach. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(7):e012410.

doi pubmed - Gurjar H, Saad M, Ali N, Regmi S, Upreti P, Karna S, Balaram SK, et al. Post myocardial infarction left ventricular intramural dissecting hematoma: a case report describing a very rare complication. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22(1):83.

doi pubmed pmc - Tanabe J, Okazaki K, Endo A, Tanabe K. Left ventricular intramyocardial dissecting hematoma. CASE (Phila). 2021;5(6):349-353.

doi pubmed pmc - Vargas-Barron J, Roldan FJ, Romero-Cardenas A, Molina-Carrion M, Vazquez-Antona CA, Zabalgoitia M, Martinez Rios MA, et al. Dissecting intramyocardial hematoma: clinical presentation, pathophysiology, outcomes and delineation by echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2009;26(3):254-261.

doi pubmed - Lee TJ, Roslan A, Teh KC, Ghazi A. Intramyocardial dissecting haematoma mimicking left ventricular clot, a rare complication of myocardial infarction: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2019;3(2):ytz056.

doi pubmed pmc - Maselli D, Micalizzi E, Pizio R, Audo A, De Gasperis C. Posttraumatic left ventricular pseudoaneurysm due to intramyocardial dissecting hematoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64(3):830-831.

doi pubmed - Silverstein JR, Tasset MR, Dowling RD, Alshaher MM. Traumatic intramyocardial left ventricular dissection: a case report. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19(12):1529.e1525-e1528.

doi pubmed - Alexandre A, Silveira J, Sa I. Chronic intramyocardial dissecting haematoma: multimodality imaging. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(23):2132.

doi pubmed - Ksiazczyk M, Wcislo T, Warchol I, Karcz-Socha I, Grycewicz T, Plewka M. Inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and intramyocardial dissecting hematoma following blunt chest trauma. Kardiol Pol. 2024;82(2):228-230.

doi pubmed - Vuruskan E, Alic E, Duzen I, Kaplan M, Altunbas G, Sucu M. An unusual complication due to a standard coronary angioplasty procedure: intramyocardial dissecting hematoma. Anatol J Cardiol. 2021;25(6):E22-E23.

doi pubmed pmc - Leitman M, Tyomkin V, Sternik L, Copel L, Goitein O, Vered Z. Intramyocardial dissecting hematoma: two case reports and a meta-analysis of the literature. Echocardiography. 2018;35(2):260-266.

doi pubmed - Rossi Prat M, de Abreu M, Reyes G, Wolcan JD, Saenz JX, Kyle D, Antonietti L, et al. Intramyocardial dissecting hematoma: a mechanical complication needing surgical therapy? JACC Case Rep. 2022;4(21):1443-1448.

doi pubmed pmc

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.