| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com/ |

Case Report

Volume 15, Number 12, December 2024, pages 382-386

An Abnormal Case of Malignant Catatonia in a Previously Healthy Young Female With Unexplained Neurological Symptoms

Shiva Kotharia, b, Basim Ahmed Khana, Molly Nguyena, Sara H. Gleasona

aDepartment of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS 39216, USA

bCorresponding Author: Shiva Kothari, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS 39216, USA

Manuscript submitted September 9, 2024, accepted October 18, 2024, published online October 30, 2024

Short title: Malignant Catatonia With Neurology Symptoms

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc4327

| Abstract | ▴Top |

This is a case report of a previously healthy 26-year-old female with unexplained neurological symptoms that eventually developed malignant catatonia. Because malignant catatonia has a range of clinical manifestations, making prompt diagnosis a challenging task. Due to her relapsing symptoms, the patient was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit three times in less than 2 months, and eventually recovered with high doses of lorazepam and several electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) treatments after a stay in the intensive care unit (ICU). This case highlights the importance of avoiding of antipsychotics with dopamine blockade prior to administering a standardized catatonia rating scale in patients with negative symptoms, especially those who have unexplained neurological symptoms or vital sign abnormalities. It also emphasizes the importance of definitive decision-making in pursuing ECT treatment for patients with suspected malignant catatonia, as our patient showed remarkable improvement after ECT. Ultimately, more research is needed to study this rare illness to standardize procedures for treatment of malignant catatonia.

Keywords: Malignant catatonia; Electroconvulsive therapy; Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Malignant catatonia, a life-threatening subtype of catatonia, is characterized by autonomic instability, mutism, posturing, stupor, rigidity, leukocytosis and elevated creatinine kinase (CK) [1]. Due to its similar initial presentation to neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) and other life-threatening illnesses including encephalopathy and severe sepsis, a clear diagnosis can often be delayed, which allows for its further progression and lethality [2]. Although there have been numerous case reports of patients with psychiatric illness who subsequently developed catatonia, there are fewer case reports published that establish a well-defined link between psychiatric illness and, the potentially lethal subtype of catatonia, malignant catatonia. In addition, there are many case reports linking malignant catatonia with neurological disorders like anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis [3]. Diagnostic challenges are present with malignant catatonia because of atypical presentations, and absence of a clear etiology [4].

We report a case of a previously healthy young female who presented to our hospital with an atypical but life-threatening malignant catatonia.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

The case report describes a patient who is a 26-year-old female who arrived at our hospital with psychotic symptoms including persecutory delusions and auditory hallucinations. She was previously high functioning prior to her symptoms, completing her graduate school degree a few months prior to her hospitalization. Her past psychiatric history includes a diagnosis of unspecified bipolar disorder, after she had a week-long hospitalization for a manic-like behavior several years ago, and a more recent brief hospitalization a few weeks prior during which she was initiated on oral aripiprazole. She had no significant past medical history including no history of seizures or family history of psychiatric illness. Her psychosocial history was notable for her being unmarried and having no biological kids, with no notable history of substance use. During her most recent hospitalization, her vital signs and lab values including complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), blood alcohol level (BAL), urinalysis (UA), urine drug screen (UDS), were noted to be unremarkable. On the exam, patient was noted to be delusional and having hallucinations but had no relevant neurological or other physical exam abnormalities. After initiation of oral aripiprazole 5 mg, the delusions and hallucinations were notably diminished. The patient was transitioned to aripiprazole long-acting injectable (LAI) 400 mg and discharged in a stable condition.

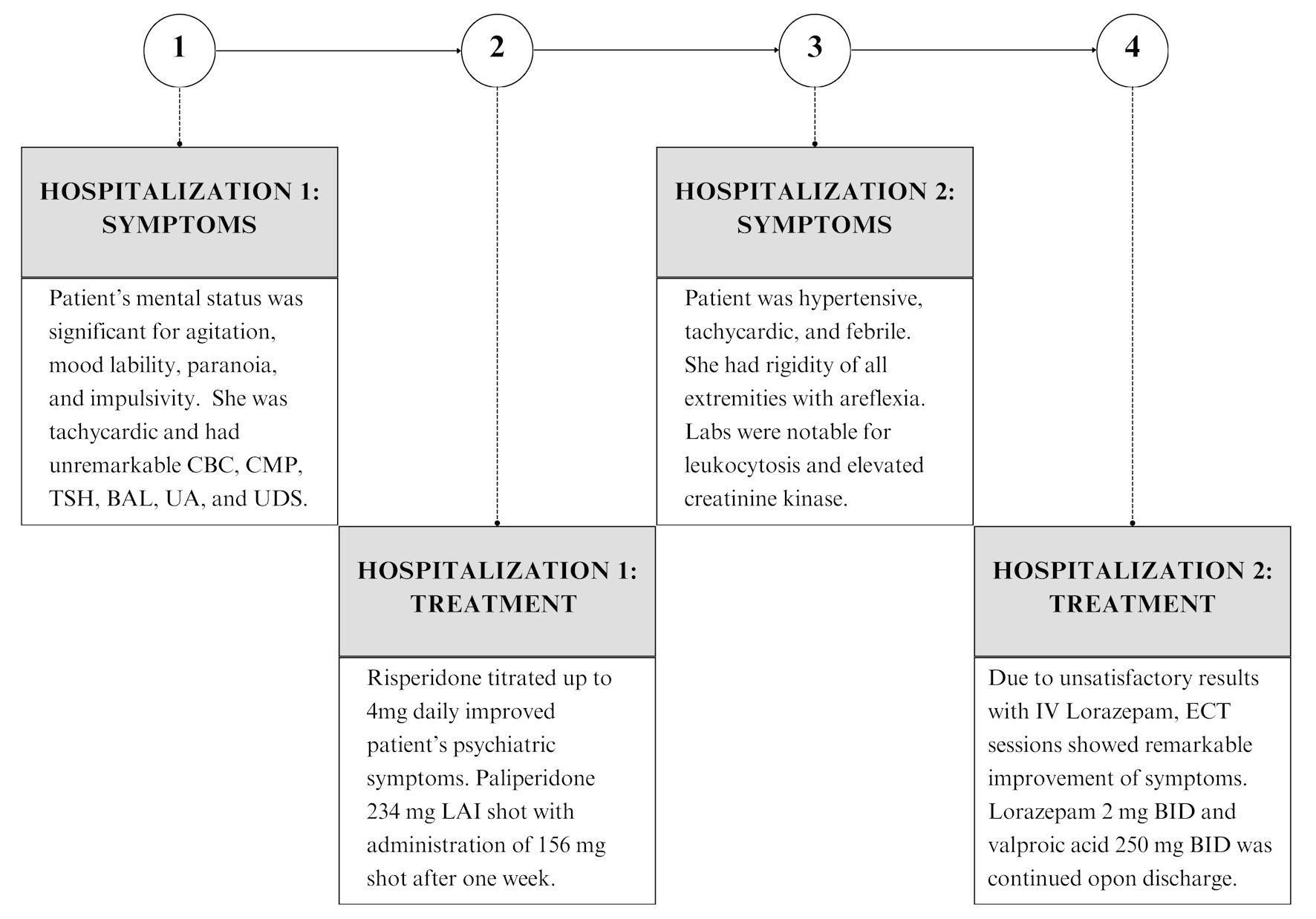

The patient relapsed just a few weeks after her most recent hospitalization and was sent to the emergency department (ED) exhibiting psychotic and mood symptoms. The mental status exam was significant for agitation, mood lability, paranoia regarding her family members, and impulsivity. While the pulse was noted to be tachycardic at 120, the rest of the vital signs were within normal limits. The lab values including CBC, CMP, TSH, BAL, UA, and UDS were again noted to be unremarkable (Fig. 1). The patient was subsequently admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit. The medication adjustments during this hospitalization included initial augmentation of aripiprazole to 30 mg nightly, with subsequent discontinuation and switch to quetiapine up to 300 mg due to lack of benefit with aripiprazole. Temazepam 15 mg nightly and clonazepam 1 mg twice a day (BID) were further added to the regimen as well. There was a lack of response to these changes.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Timeline of symptoms and treatment depicting the patient’s hospitalization (from symptom onset to treatment milestones). ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; CBC: complete blood count; CMP: comprehensive metabolic panel; TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone; BAL: blood alcohol level; UA: urinalysis; UDS: urine drug screen; LAI: long-acting injectable; BID: twice a day; IV: intravenous. |

Certain atypical findings were also noted in her vital signs including tachycardia to the 120s that did not resolve until given a beta-blocker. During her neurological exam, she had limited upgaze bilaterally, her left eye was in the “down and out position” at baseline, and she had bilateral ptosis that did not respond to the ice pack test. It was also noted she had lower facial weakness via direct muscle testing but no other muscle weakness otherwise. Her reflexes, muscle tone, strength, coordination, gait, speech, orientation, and cranial nerves were intact. Therefore, she was diagnosed with bilateral ptosis, limited abduction of right eye, and mild lower face bifacial weakness. Neurology and endocrinology were consulted further to rule out any neurologic or medical causes of this presentation. TSH, triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4), thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI), thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody (TRA), thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO), antinuclear antibody (ANA), syphilis screen, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), folate, vitamin B12, heavy metals, urine gonorrhea and chlamydia, porphyrins, herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1 and 2, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), lumbar puncture (LP), electroencephalogram, and anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis antibodies tests were performed. All the tests and imaging were noted to be non-significant. Electromyography and nerve conduction velocity tests were also performed, and results indicated that no neuromuscular junction process was involved. The neurology team followed the case closely during the hospitalization with serial exams daily. At the end of their consultation, they concluded that the ptosis and facial movement limitation were also not felt to be due to an underlying neuromuscular disease, and they subsequently signed off.

Further medication adjustments during this hospitalization included the discontinuation of quetiapine and use of haloperidol, chlorpromazine and valproic acid, with eventual discontinuation of those medications due to lack of response. The patient underwent a trial of risperidone, titrated up to 4 mg daily dose, and there was a subsequent improvement in psychiatric symptoms. As a result, a paliperidone 234 mg LAI shot was administered with administration of a second shot of 156 mg a week after. Oral risperidone was discontinued, and the patient was discharged after a month-long hospitalization (Fig. 1).

Diagnosis

The patient was brought to the ED again after about 10 days of deteriorating mental status at home. Collateral history revealed that a few days after discharge, the patient started to report significant fatigue, requiring spoon-feeding and assistance with drinking. She was unable to perform most of her activities of daily living (ADLs) either.

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient was noted to be unresponsive and ill, appearing with significant vital instability. Blood pressure (BP) was noted to be 175/108 mm Hg, heart rate 170, temperature 37.81 °C, and respiratory rate of 20 with a peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 98%. She had an adequate urine output but needed assistance with toileting. The patient was found to have rigidity of all four extremities with areflexia. She was unable to follow commands, and her skin was warm to touch. Labs were notable for elevated white blood cell count (WBC) of 12,000 and blood CK of 6,500 (Fig. 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was non-significant. Differential diagnosis at this time included NMS, malignant catatonia, encephalitis, and sepsis. In the ED, the patient was given intravenous (IV) midazolam, dantrolene, diphenhydramine, bromocriptine and IV fluids. With the lack of robust response to medical interventions in the ED, the concern for rhabdomyolysis given the elevated CK, and acute hypoxic respiratory failure given her lack of responsiveness, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

In the ICU, further workup to rule out medical causes of altered mental status was carried out, including obtainment of blood cultures, procalcitonin, urine analysis and culture, which all came back negative. Patient was prophylactically kept on vancomycin and cefepime during this time while an LP was performed to rule out auto-immune encephalitis and meningitis, which came back benign. MRI brain was also performed and did not reveal any significant abnormality.

With the occurrence of negative test results, the working diagnosis was narrowed down to malignant catatonia without ruling out NMS as they can often co-occur. Given that our patient had unexplained neurological symptoms, in addition to her malignant catatonia, encephalitis remained on our differential diagnosis. Nonetheless, the progression and potential lethality of malignant catatonia led us to pursue definitive treatment for it first. To assess the severity of catatonia, the Bush Francis Catatonia Scale (BFCS) was used with an initial score noted to be 15, with points for mutism, rigidity, vital sign abnormalities, withdrawal immobility, staring and posturing.

Treatment

As an indicated treatment for catatonia, a lorazepam trial was initiated with administration of 2 mg of lorazepam every 6 h (IV), with subsequent increase to 3 mg every 6 h. After 3 days of lorazepam treatment, the option to pursue electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was finally decided in view of unsatisfactory results with IV lorazepam, with only a minimal decrease in BFCS. The patient continued to have high levels of CK, tachycardia, hyperthermia, along with immobility, rigidity, mutism and withdrawal that led us to pursue a more definitive treatment for malignant catatonia.

After the first session of ECT, the patient was noted to have less rigidity, while her mental status was still significant for disorientation, mutism and decreased oral intake, and her BFCS reduced by more than half. The patient continued to receive more ECT sessions (three times a week). Significant alleviation in symptoms were gradually observed, and by her 11th and final session of ECT, the patient was doing well overall with her BFCS at 0. Her mental status had returned to baseline as she was noted to be cooperative, able to follow commands, and exhibited a logical thought process. Oral lorazepam 2 mg BID was continued upon discharge.

Follow-up and outcomes

After discharge, the patient has continued to do well. Her vital signs have remained within normal limits, and she has not shown any focal neurologic deficits that she displayed during her hospitalizations. Her BFCS has remained at 0 throughout her many outpatient visits. She has slowly transitioned to her regular daily life routine, including returning to work, although not to her baseline prior to the illness. Given that it has been a little over a year since discharge from the hospital, a slow recovery is to be expected. She continues to take lorazepam, as it has been noticed that her symptoms relapse each time an attempt for tapering has been made. She is also on valproic acid 250 mg BID which is noted to help with mood stability. She is compliant with her outpatient visits and medication and has not needed any further in-patient hospitalization since her last hospital discharge (Fig. 1).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Catatonia is a neuropsychiatric condition characterized by abnormal movements, abnormal behaviors and withdrawal that can often be associated with psychiatric conditions. Malignant catatonia is a subtype of catatonia that is potentially lethal. This case is an abnormal presentation of malignant catatonia with unexplained neurological symptoms in which the patient had successful resolution of symptoms via ECT.

Relevant medical literature

In terms of contextualizing our case within literature, our patient had a significant gap between initial presentations of symptoms to ultimate treatment of her malignant catatonia with ECT. This is like many malignant catatonia cases in literature, in which patient’s hospital course was prolonged with lack of remission of symptoms until ultimate treatment with ECT [5-7]. Interestingly, our patient did not have early intervention of Ativan in her clinical course, which has been shown to shorten the course of the malignant catatonia in other cases [1, 5]. It is unclear if the lack of early initiation of treatment compared to the introduction of antipsychotics worsened our patient’s clinical course, which was the case with other patients [5]. Finally, other patients improved on a combination of dantrolene and other agents while there was only marginal improvement in our case [1, 5]. Ultimately, in a case series of 117 patients with malignant catatonia, it was shown both early doses of Ativan as well as initiation of ECT were the most effective treatments to stop the progression of this disease course [1].

The link between catatonia and neurologic symptoms in our case report is not uncommon in literature. A recent systemic review indicated that over 60% of catatonia caused by a medical condition is due to direct central nervous system involvement [4]. Interestingly, there is a significant overlap between catatonia, especially malignant catatonia, and the most common autoimmune brain disease subtype, anti-NMDA receptor autoimmune encephalitis [4, 8]. Although our patient’s anti-NMDA receptor antibody was negative, the unexplained neurological symptoms could provide further evidence to keep malignant catatonia on the differential diagnosis in catatonia patients with concurrent neurologic symptoms.

Strengths and limitations

One strength in the treatment team’s approach to the case is strong outpatient follow-up in the initial stages of the case. That contributed to a positive patient-doctor relationship, which allowed for the patient’s mother to bring the patient back for multiple hospitalizations when her symptoms were not improving. This extended to post-hospitalization where the patient regularly attends outpatient psychiatric appointments to continue her positive trajectory towards a full recovery. It has allowed the outpatient team to augment her benzodiazepine with a mood stabilizer given her labile mood after discharge.

Another strength of the case report is the definitive pursing of ECT after a 3-day trial of progressively increasing dose of IV lorazepam. The patient showed remarkable response to just a few ECT sessions that was not seen with medication alone. This led the patient to an earlier discharge from the hospital and a quicker recovery overall.

One limitation in this study is noted to be the presence of unexplained neurological symptoms which are noted in the initial course of patient’s psychiatric illness including muscle weakness and proptosis. While no definite conclusion could be made on the etiology, it remains unclear if those symptoms were interlinked to the later occurrence of malignant catatonia. Given the link between autoimmune encephalitis and malignant catatonia, it is unclear if this patient could have had seronegative autoimmune encephalitis.

Another limitation of the study was the administration of antipsychotics to treat the underlying psychiatric illness in the earlier part of the patient’s hospital course. This includes administering two LAIs to the patient during her first two hospitalizations, which remain effective in the system for several weeks. Given the link between malignant catatonia and the administration of antipsychotics, especially those that have D2 receptor blockade, these medications could have precipitated the patient’s eventual malignant catatonia [8]. While the development of malignant catatonia could be multifactorial, the addition of antipsychotics for this patient was ultimately not beneficial for definitive treatment as it led to repeated hospitalizations over the course of several months.

Learning points

This case is unique due to the concurrent prevalence of malignant catatonia, unexplained neurological symptoms and delay in diagnosis. It underscores the need for prompt evaluation and suspicion of catatonia, as well as potential avoidance of antipsychotics prior to administering a standardized catatonia rating scale in patients presenting to the ED with negative symptoms with a broad differential diagnosis, especially those with unexplained neurologic symptoms or vital sign abnormalities. It emphasizes the importance of definitive decision-making in pursuing ECT treatment for patients with suspected malignant catatonia, as our patient showed remarkable improvement in weeks during ECT sessions. This case highlights the need for a further understanding of how psychiatric or medical illnesses can lead to malignant catatonia, considering its potential lethality.

Given the lack of extensive literature on malignant catatonia, with less than 150 published case reports overall, it is essential for continued dissemination of information regarding this potentially lethal psychiatric disease. Although the underlying etiology of this patient’s diagnosis could not be conclusively determined, her underlying psychiatric illness contributed to her symptoms, which is consistent with the literature where there are many cases of malignant catatonia that have primarily psychiatric origins [1]. However, what is unclear is how much her neurologic symptoms contributed to the worsening of her symptoms and eventual development of malignant catatonia. Prompt suspicion and diagnosis of catatonia using standardized scales such as a Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale can aid in this endeavor. Psychiatric clinicians as well as ED physicians should have adequate training in properly administering this scale. Eventually, more research, published case reports, and basic research are needed in this rare disease to standardize protocols for diagnosing and treating malignant catatonia.

Acknowledgments

Special acknowledgment to Dr. Allen Richert, who assisted in the clinical care of the patient by providing ECT treatments.

Financial Disclosure

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent for publication was obtained. The patient was contacted, and the risks, benefits, and alternatives for this case report were explained to the patient. There was also an opportunity for the patient to ask questions, and the patient signed a consent form, and it was witnessed and is in the patient’s medical chart. The primary author performed the informed consent.

Author Contribution

SK, the major contributor in writing manuscript, gathered the history from the patient and family, obtained consent for publication, and was one of the physicians overseeing the treatment of the patient. BK served as the editor of the manuscript, was the major contributor in writing the manuscript and one of the physicians overseeing the treatment of the patient. MN was the editor of the manuscript and major contributor in writing the manuscript. SG served as the editor of the manuscript and was the supervising physician overseeing the treatment of patient.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

MC: malignant catatonia; ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; NMS: neuroleptic malignant syndrome; CBC: complete blood count; CMP: comprehensive metabolic panel; TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone; BAL: blood alcohol level; UA: urinalysis; UDS: urine drug screen; LAI: long-acting injectable; ED: emergency department; BID: twice a day; T3: triiodothyronine; T4: thyroxine; TSI: thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin; TRA: thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody; TPA: thyroid peroxidase antibodies; ANA: antinuclear antibody; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HSV: herpes simplex virus; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; ADL: activities of daily living; BP: blood pressure; WBC: white blood cells; CK: creatinine kinase; ICU: intensive care unit; CT: computed tomography; IV: intravenous; LP: lumbar puncture; BFCS: Bush Francis Catatonia Scale

| References | ▴Top |

- Cronemeyer M, Schonfeldt-Lecuona C, Gahr M, Keller F, Sartorius A. Malignant catatonia: Severity, treatment and outcome - a systematic case series analysis. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2022;23(1):78-86.

doi pubmed - Desai S, Hirachan T, Toma A, Gerolemou A. Malignant catatonia versus neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Cureus. 2021;13(6):e15818.

doi pubmed - Rogers JP, Pollak TA, Blackman G, David AS. Catatonia and the immune system: a review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):620-630.

doi pubmed - Connell J, Oldham M, Pandharipande P, Dittus RS, Wilson A, Mart M, Heckers S, et al. Malignant catatonia: a review for the intensivist. J Intensive Care Med. 2023;38(2):137-150.

doi pubmed - Raja M, Altavista MC, Cavallari S, Lubich L. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and catatonia. A report of three cases. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;243(6):299-303.

doi pubmed - Gerra ML, Mutti C, Luvie L, Daniel BD, Florindo I, Picetti E, Parrino L, et al. Relapsing-remitting psychosis with malignant catatonia: a multidisciplinary challenge. Neurocase. 2022;28(1):126-130.

doi pubmed - Wong S, Hughes B, Pudek M, Li D. Malignant catatonia mimicking pheochromocytoma. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2013;2013:815821.

doi pubmed - Rogers JP, Oldham MA, Fricchione G, Northoff G, Ellen Wilson J, Mann SC, Francis A, et al. Evidence-based consensus guidelines for the management of catatonia: Recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2023;37(4):327-369.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.