| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jmc.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 1, January 2025, pages 6-10

Prolonged SARS-CoV-2 Viremia in an Immunocompromised Patient

Mohammed Abdulrasaka, b, c, Sohail Hootaka, b

aDepartment of Clinical Sciences, Malmo, Lund University, Malmo, Sweden

bDepartment of Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Skane University Hospital, Malmo, Sweden

cCorresponding Author: Mohammed Abdulrasak, Department of Clinical Sciences, Malmo, Lund University, Malmo, Sweden

Manuscript submitted October 26, 2024, accepted November 9, 2024, published online November 12, 2024

Short title: SARS-CoV-2 Viremia

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc5064

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Immunocompromised patients, especially those receiving B-cell depleting therapies, are at risk for developing atypical presentation with regard to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, with the potential for diagnostic delay and adverse outcomes if such delay occurs. A 66-year-old female with history of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) with previous pulmonary involvement, treated with rituximab and low-dose prednisolone, presented with prolonged fever and cough after having been treated at home for a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection in early July 2023. The patient had a prolonged course over several months with constitutional symptoms such as fever, cough and malaise. During the investigation, which encompassed a wide range of microbiological and immunological tests, the patient was initially thought to have a flare of GPA which she was treated for without appreciable improvement, then for multiple microbiological organisms without appropriate resolution of the patient’s symptoms. The differential diagnosis of prolonged SARS-CoV-2 infection was reconsidered in October 2023, and then confirmed by the presence of SARS-CoV-2 viremia through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of the blood. The patient received a prolonged course of antiviral therapy with complete clinical, virological and radiological resolution. Prolonged SARS-CoV-2 infection with viremia in immunocompromised individuals needs to be considered on the differential diagnosis list in such patients presenting with constitutional symptoms, with PCR testing of the blood as a simple and effective way to establish the diagnosis.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2; Immunocompromised patient; PCR

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been responsible for one of the worst healthcare crises of this century [1]. The virus initially infects the upper airways, with symptoms ranging all the way from being asymptomatic to having common cold symptoms to severe infection with fatal pneumonitis, the latter especially in older individuals and patients with immunocompromised status [2, 3]. Vaccination is thought to be protective against the occurrence of severe disease, making it recommended in the aforementioned groups [4].

SARS-CoV-2 severity correlates well with the degree of immunocompromise, with immunocompromised individuals having poor outcomes as compared to those without immunosuppression [5, 6]. This is especially true in solid-organ transplant recipients [6], patients on high-dose corticosteroids [7] and patients treated with CD20-depleting therapy [8]. In these patients, the antibody responses to both vaccine and primary infection with SARS-CoV-2 may be too weak to mount any significant protection against the virus [9]. In addition, immunocompromised status may entail a protracted SARS-CoV-2 infection with mild, yet distressing, symptoms for the patient with “flares” of waxing and waning viral activity [10]. Such a disease course may be confusing for the treating physician of such patient, resulting in diagnostic mishaps on the road to establishing a diagnosis.

We present a case of an immunocompromised adult female patient who was found to have a prolonged SARS-CoV-2 infection. This was identified only after many months of testing and treating for multiple etiologies without sufficient clinical improvement.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 66-year-old female with medical history of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), diagnosed in 2019 on the basis of positive proteinase 3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) and pulmonary cavernous lesions on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). The initial flare was treated with cyclophosphamide and rituximab and the patient was then maintained on rituximab every 6 months and low-dose (5 mg/day) prednisolone, alongside trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PJP). The patient had received five doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and had, as far as she knew, never contracted the virus. No detectable IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were present in this patient after her vaccinations. The patient had, given her treatment, an expected B-cell depletion (undetectable CD19 and CD20 B cells) alongside low immunoglobulin levels (IgG 5.76 g/L, IgA 0.48 g/L and IgM 0.36 g/L). The patient had mild residual bronchiectasis and cavitation on follow-up CT of the chest when in remission.

The patient initially presented to the rheumatology department on July 5, 2023 with fever alongside influenza-like symptoms including mild cough and coryza. SARS-CoV-2 antigen test was performed with positive result. The patient received Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir-ritonavir) therapy for 5 days after consultation with the infectious disease service. The patient had an uneventful recovery with resolution of cough, fever and influenza-like symptoms. The symptoms recurred around July 18, 2023 with cough, fever and malaise, entailing an increase of the prednisolone dose to 7.5 mg/day. The patient’s symptoms persisted, whereby she returned to the emergency department on August 3, 2023. Labs (Table 1) showed no leucocytosis but an elevated C-reactive protein. The patient was admitted with high-dose cefotaxime (2 g thrice daily) and extensive assays to exclude bacterial, viral and fungal infection. CT of chest showed no pulmonary emboli, but an extensive left-sided infiltrate which was consistent with infectious or inflammatory changes. Nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses was negative, alongside negative sputum PJP-DNA, negative beta-D-glucan testing and blood cultures. Sputum cultures grew P. aeruginosa and the antibiotic treatment was switched to intravenous meropenem. HRCT showed progression of pulmonary lesions. The patient had no significant improvement in spite of antibiotic treatment, whereby the pulmonary lesions and symptoms were interpreted as secondary to GPA flare. The patient received rituximab treatment as per her maintenance protocol while admitted, with some improvement, whereby she was discharged on August 14, 2023.

Click to view | Table 1. Selected Labs Including SARS-CoV-2 Testing During the Patient’s Illness |

The patient’s symptoms (including fever) recurred shortly thereafter on August 17, 2023, interpreted as a symptom consistent with GPA flare. The prednisolone dose was increased to 20 mg/day with taper of 2.5 mg biweekly. In spite of this, the fever persisted alongside the dry cough. This was later interpreted, after discussions with the infectious disease consultants, as a symptom of P. aeruginosa infection which was not treated long enough. High-dose ciprofloxacin (14 days) was prescribed for a suspected worsening ascribed to P. aeruginosa. No improvement of the patient symptoms occurred. A new CT of chest was performed on August 30, 2023, showing a changed configuration of the infiltrates suggestive of infectious, inflammatory or hemorrhagic lesions.

The patient was then admitted again on September 19, 2023 to undergo bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). BAL fluid was sent off for bacterial, viral, mycobacterial and fungal diagnostics. The BAL fluid was positive for P. aeruginosa and, surprisingly, SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The cycle threshold (Ct) value for the SARS-CoV-2 was 31, which deemed it, after consultation with the infectious disease service, a false positive finding reflecting the initial infection in July 2023. The worsening was attributed to be a P. aeruginosa pulmonary infection, whereby intravenous meropenem and oral ciprofloxacin were to be administered intravenously through the “home intravenous antibiotic” service.

The patient had no appreciable improvement of either the cough or the fever, whereby she was again admitted on October 10, 2023 for re-evaluation of the symptoms while on continued antibiotic treatment. CT of chest on October 11, 2023 showed increased right lower lobe consolidation. Renewed microbiological survey was negative apart from a slightly elevated beta-D-glucan in serum (10.7 pg/mL, considered positive if > 7.0 pg/mL). The patient received high-dose TMP-SMX for the treatment of suspected PJP. Given the patient’s prolonged symptoms and the intermittently positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests, it was elected to re-consider SARS-CoV-2 as a potential causative agent of the patient’s symptoms. This was pursued through nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 testing (as part of “multiplex” respiratory panel) and looking for SARS-CoV-2 viremia in the plasma.

Results, treatment and follow-up

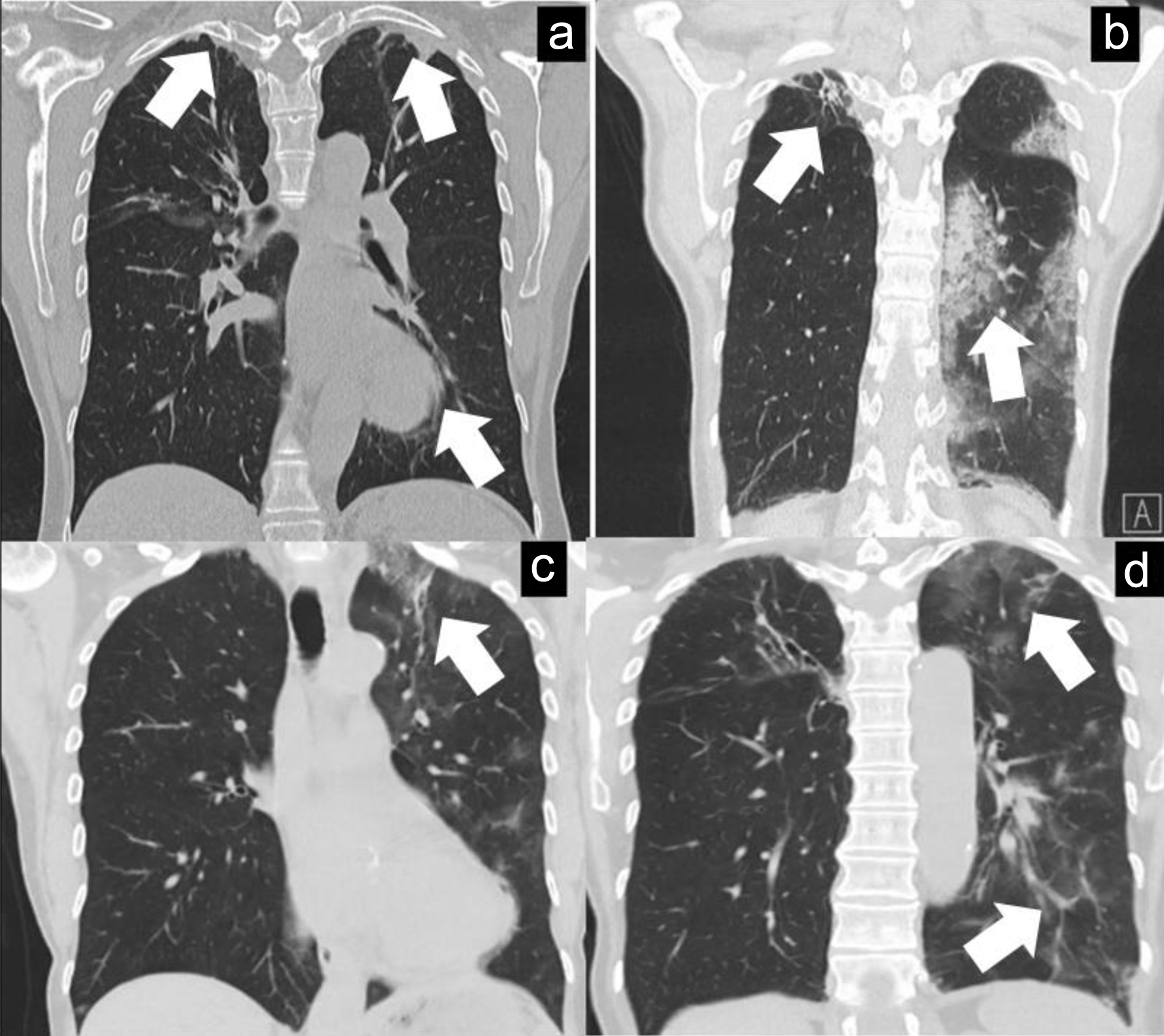

SARS-CoV-2 positivity was established in the nasopharynx and the plasma on the October 16, 2023. The Ct value was not computable for the nasopharynx sample, but for the plasma sample it was 36, suggesting low-level viremia. Consultation with the infectious disease service was obtained, and a prolonged Paxlovid course of 10 days was administered given the patient’s degree of immunosuppression and long duration of symptoms. The patient had resolution of the dyspnea, malaise, fever and cough on day 2 of the treatment course. SARS-CoV-2 testing (nasopharynx and plasma PCR) was performed twice, once in the middle of the treatment course (October 20, 2023) and a week after completed antiviral treatment (November 1, 2023), with negative results from both the nasopharynx and the plasma. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the radiological course of the patient’s illness. The patient had no recurrence of the cough, fever or malaise and made an uneventful recovery.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) HRCT of chest (March 28, 2023) done for follow-up purposes with small right-sided apical traction bronchiectasis (and slightly in left upper lobe) with small cavity (not entirely visualised) and left lower lobe infiltrate (white arrows) which is considered as a rest after previous pulmonary involvement of GPA. (b, c) HRCT of chest (August 5, 2023) with increased consolidation in left upper and lower lobes mainly (white arrows) which may be consistent with infectious or inflammatory process. (d) HRCT of chest (August 30, 2023) with decreased left lower lobe infiltrates but persistence of upper lobe infiltrates (white arrows). GPA: granulomatosis with polyangiitis; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a, b) HRCT of chest (October 11, 2023) with increased consolidation in right lower lobe and decreased left lung infiltrates (white arrows). (c, d) HRCT of chest (December 11, 2023) post-treatment for SARS-CoV-2 with mainly older changes present and potentially a small remaining infiltrate in the right lower lobe (white arrows). HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case illustrates the complex differential diagnostic thought process when dealing with a patient suffering from known immunocompromised state due to treatment for GPA presenting with upper respiratory tract and constitutional symptoms. The main differential diagnoses which were entertained in this case were flaring of the original disease process, a bacterial/fungal infection and finally persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection. The presence of non-specific radiological findings, positive BAL for P. aeruginosa and positive beta-D-glucan tests may be considered as important but somewhat misleading findings on the way to establishing the diagnosis, and the positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2 in the blood as being the test clinching the diagnosis.

The radiological findings in both GPA, bacterial/fungal disease processes involving the lungs and SARS-CoV-2 are highly non-specific and always require clinical correlation with other ancillary testing. The positive culture for P. aeruginosa may have been a true positive finding, albeit appropriate treatment targeting it resulted in no improvement which suggests colonization rather than active infection with the organism, especially provided the residual bronchiectasis and cavitation which this patient had due to her initial GPA flare [11]. The marginally positive beta-D-glucan test is, given the course of the patient’s illness, most likely a false positive finding which occurred due to antibiotics (including meropenem) in the patient’s serum interacting with the immunoassay testing for beta-D-glucan [12].

Patients receiving B-cell depleting therapies are at risk for atypical SARS-CoV-2 infections [13], as occurred in this patient. Prolonged viral shedding in patients with rituximab treatment has been reported previously [14]. This patient was at increased risk for such a response especially given that the patient had no IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in spite of having undertaken multiple booster vaccinations, a scenario that is not uncommon and reported in up to 50% of patients receiving regular CD20-depleting therapies [15]. In addition to this, false negative SARS-CoV-2 testing from the nasopharynx has been previously reported in immunocompromised individuals [16], and therefore in cases with high index of suspicion for the diagnosis, there needs to be more aggressive testing, preferably with blood PCR samples as in our case. This is especially true given that, despite the high prevalence of vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2, there is an excessive predisposition for these infections occurring in the immunocompromised individuals, with up to 25% of all SARS-CoV-2 occurring in these individuals [7].

In conclusion, it is imperative for the clinician treating immunocompromised individuals to consider atypical presentation of typical infections, especially with regard to SARS-CoV-2 infection. In this case, a prolonged SARS-CoV-2 infection was interpreted as GPA flare, bacterial pneumonia, and PJP and then finally prolonged SARS-CoV-2 infection after a laborious diagnostic thought process.

Learning points

There are multiple learning points from this case, with the main one being aware of the risk for prolonged SARS-CoV-2 infection in immunocompromised patients and performing blood testing for viral PCR when this is suspected, even when faced with negative nasopharyngeal PCR testing. Another learning point involves the interpretation of beta-D-glucan tests, as several medications, including certain antibiotics, may interfere with that specific test and cause false-positive readings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend thanks to the patient for her consent to use the case.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Verbal consent was obtained to use the case details in both written and visual media.

Author Contributions

Mohammed Abdulrasak and Sohail Hootak contributed to writing and editing the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Pollard CA, Morran MP, Nestor-Kalinoski AL. The COVID-19 pandemic: a global health crisis. Physiol Genomics. 2020;52(11):549-557.

doi pubmed pmc - DeWolf S, Laracy JC, Perales MA, Kamboj M, van den Brink MRM, Vardhana S. SARS-CoV-2 in immunocompromised individuals. Immunity. 2022;55(10):1779-1798.

doi pubmed pmc - Joshee S, Vatti N, Chang C. Long-term effects of COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(3):579-599.

doi pubmed pmc - Di Fusco M, Lin J, Vaghela S, Lingohr-Smith M, Nguyen JL, Scassellati Sforzolini T, Judy J, et al. COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness among immunocompromised populations: a targeted literature review of real-world studies. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21(4):435-451.

doi pubmed pmc - Fung M, Babik JM. COVID-19 in immunocompromised hosts: what we know so far. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(2):340-350.

doi pubmed pmc - Avery RK. Update on COVID-19 therapeutics for solid organ transplant recipients, including the omicron surge. Transplantation. 2022;106(8):1528-1537.

doi pubmed pmc - Evans RA, Dube S, Lu Y, Yates M, Arnetorp S, Barnes E, Bell S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on immunocompromised populations during the Omicron era: insights from the observational population-based INFORM study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023;35:100747.

doi pubmed pmc - Jones JM, Faruqi AJ, Sullivan JK, Calabrese C, Calabrese LH. COVID-19 outcomes in patients undergoing B cell depletion therapy and those with humoral immunodeficiency states: a scoping review. Pathog Immun. 2021;6(1):76-103.

doi pubmed pmc - Pearce FA, Lim SH, Bythell M, Lanyon P, Hogg R, Taylor A, Powter G, et al. Antibody prevalence after three or more COVID-19 vaccine doses in individuals who are immunosuppressed in the UK: a cross-sectional study from MELODY. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5(8):e461-e473.

doi pubmed - Gandhi RT, Castle AC, de Oliveira T, Lessells RJ. Case 40-2023: a 70-year-old woman with cough and shortness of breath. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(26):2468-2476.

doi pubmed - Tashiro H, Takahashi K, Tanaka M, Komiya K, Nakamura T, Kimura S, Tada Y, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of microscopic polyangiitis with bronchiectasis. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(2):303-309.

doi pubmed pmc - Liss B, Cornely OA, Hoffmann D, Dimitriou V, Wisplinghoff H. 1,3-beta-D-glucan contamination of common antimicrobials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(4):913-915.

doi pubmed - Tepasse PR, Hafezi W, Lutz M, Kuhn J, Wilms C, Wiewrodt R, Sackarnd J, et al. Persisting SARS-CoV-2 viraemia after rituximab therapy: two cases with fatal outcome and a review of the literature. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(2):185-188.

doi pubmed pmc - Zahid A, Fahim A, Gupta L, Adenitan A, Sheeran T, Goddard S. Prolonged viral shedding following COVID-19 infection in a rheumatoid patient on rituximab treatment. Ann Thorac Med. 2024;19(2):175-176.

doi pubmed pmc - Rose E, Magliulo D, Kyttaris VC. Seroconversion among rituximab-treated patients following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine supplemental dose. Clin Immunol. 2022;245:109144.

doi pubmed pmc - Beam E, Meyer ML, JC O’Horo, Breeher LE. False-negative nasopharyngeal severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in immunocompromised patients resulting in healthcare worker exposures. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2022;43(12):1971-1972.

doi pubmed pmc

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.